WHITECROSS ESTATE London EC1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whitecross Street Estate

WHITECROSS STREET ESTATE WHITECROSS Publica 2010 WHITECROSS STREET ESTATE 2010 Dedicated to the memory of MichaeL SMOUGhtON 11th December 1974 – 20th November 2010 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 • PORTRAIT OF THE ESTATE 1.1 Historical Timeline 1.2 People 1.3 Buildings 1.4 Public Space and Gardens 1.5 Individual Spaces 1.6 Routes 2 • WALKS AND MEETINGS 3 • QUOTES 4 • POLITICS AND POLICIES 5 • PEABODY 6 • PRINCIPLES FOR THE FUTURE APPENDIX INTRODUCTION 5 In September 2010 the Peabody Tenants’ Association Whitecross Street (PTAWS) commissioned Publica to produce a report on the public spaces and amenities of the Whitecross Street estate. Funding for the report was provided by Peabody. The purpose of the report is to provide evidence of the strengths and weaknesses of the estate’s public realm, including residents’ own experiences and opinions of the estate. From this evidence, a proposed vision and set of principles for the future of the estate has been drawn up. The vision and principles are intended to help residents in discussions with Peabody and other stakeholders about future improvements and developments on the estate. The report provides a snapshot portrait of the estate as encountered by Publica in October and November 2010. At the heart of the report is the presentation of residents’ opinions and concerns about the estate’s public spaces and amenities. These were collected on a series of walks and meetings, as well as via email correspondence and a project blog. These opinions are presented as a series of quotes, which are arranged by theme and cross-referenced with specific spaces on the estate. -

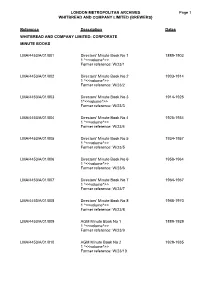

{BREWERS} LMA/4453 Page 1 Reference Description Dates

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 WHITBREAD AND COMPANY LIMITED {BREWERS} LMA/4453 Reference Description Dates WHITBREAD AND COMPANY LIMITED: CORPORATE MINUTE BOOKS LMA/4453/A/01/001 Directors' Minute Book No 1 1889-1903 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/1 LMA/4453/A/01/002 Directors' Minute Book No 2 1903-1914 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/2 LMA/4453/A/01/003 Directors' Minute Book No 3 1914-1925 1^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/3 LMA/4453/A/01/004 Directors' Minute Book No 4 1925-1934 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/4 LMA/4453/A/01/005 Directors' Minute Book No 5 1934-1957 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/5 LMA/4453/A/01/006 Directors' Minute Book No 6 1958-1964 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/6 LMA/4453/A/01/007 Directors' Minute Book No 7 1964-1967 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/7 LMA/4453/A/01/008 Directors' Minute Book No 8 1968-1970 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/8 LMA/4453/A/01/009 AGM Minute Book No 1 1889-1929 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/9 LMA/4453/A/01/010 AGM Minute Book No 2 1929-1935 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/10 LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 WHITBREAD AND COMPANY LIMITED {BREWERS} LMA/4453 Reference Description Dates LMA/4453/A/01/011 Managing Directors' Committee Minute Book 1937-1939 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/11 LMA/4453/A/01/012 Board Papers 1945-1947 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/12 LMA/4453/A/01/013 Policy Meetings Minute Book 1946 1 ^<<volume^>> Former reference: W/23/13 LMA/4453/A/01/014 Policy Meetings Minute Book 1947 -

Barbican Association NEWSLETTER 1 the BARBICAN ASSOCIATION OFFICERS

NEWSLETTER www.barbicanassociation.com August 2020 While The City Sleeps CHAIR’S CORNER Working from home or walking pedestrians and cyclists on narrow City to work? streets and hence, to restrict access for motor work late into the evening and into the s I wander round a still-deserted City, I vehicles. There is an elaborate phased plan weekend, to allow social distancing on work wonder about all the empty offices, to increase the number of traffic restrictions sites, The City took a helpful line. Awith their attentive, but surely bored (see www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/services/ At the May planning committee meeting, security staff and their blinking screen savers. streets/ covid-19-city-streets), which includes the senior environmental health officer I am struck too by how much new, an interactive map where we can give pointed out that The City already has a unoccupied office space there is, completed feedback on individual streets. So far, there process for allowing out-of-hours working on or still being built. still are not many pedestrians around, though construction sites. It receives around 1200 When I wondered aloud to the City I wish that cyclists would use their own parts such applications a year, for such functions planners about whether or not the pandemic of the road and not ride on pavements. as 24-hour concrete pours or for bringing in and its aftermath would prompt a rethink of That map does not include the Beech large cranes at the weekend when roads are the draft Local Plan’s aim to deliver a Street restriction to all but zero-emissions less busy. -

Culture Mile Look and Feel Strategy

CULTURE MILE LOOK AND FEEL STRATEGY DETAILED DELIVERY PLAN 1 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 05 • The team • Structure of this document • Public and Stakeholder engagement THE AIMS 01 - Form a Culture Spine 17 02 - Take the Inside Out 35 03 - Discover and Explore 51 04 - Be Recognisable and be Different 69 SUMMARY DELIVERY PLAN 81 APPENDIX 87 • Appendix 1 - Form a Culture Spine • Appendix 2 - Take the Inside Out • Appendix 3 - Discover and Explore • Appendix 4 - Be Recognisable and be Different 3 4 CULTURE MILE LOOK AND FEEL STRATEGY INTRODUCTION 5 THE TEAM FLUID As lead consultant we are responsible for the project management, leadership and vision development. Fluid led on the site analysis, research, engagement and development of the public realm strategy. LEAD CONSULTANT ALAN BAXTER VISION DEVELOPMENT Provided heritage expertise and input into the transport, PUBLIC REALM STRATEGY movement and access strategies. CONTEMPORARY ART SOCIETY (CAS) Developed the cultural strategies that aid place activation and advised on governance considerations. SEAM Looked at the opportunities for lighting to aid wayfinding, highlight landmarks and give expression to key spaces. ARUP DIGITAL PUBLIC INFORMATION HERITAGE Developed digital tools for interactive communications CULTURAL STRATEGY LIGHTING STRATEGY LANDSCAPE AND GREENING TRANSPORT AND MOVEMENT and public information. SECURITY ARUP LANDSCAPE Developed the landscape, green infrastructure and sustainability principles and advised on management. ARUP SECURITY Advised on security matters, providing guidance on protecting people and property in the public realm. 6 STRUCTURE OF THIS DOCUMENT LOOK AND FEEL STRATEGY This document is organised into four sections: 1. PUBLIC AND STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT - Contains information on findings of engagement about Culture Mile and the Look and Feel Strategy. -

Download Master Brochure

INTRODUCTION THE BUILDING THE LOCATION THE PLANS AND SPECIFICATION THE TEAM AND OTHER INFORMATION A Confident and contemporary, Atlas is an inspired reflection of its surroundings. Standing on the axis INTRODUCTION of Shoreditch, Islington, Farringdon and the City, it’s an exciting, signature building in London’s most exhilarating neighbourhood. A portfolio of exquisite apartments with spectacular cityscape views is accommodated over 38 residential floors. Interiors and residential amenities have been designed with exceptional flair, ingenuity and APARTMENTS finesse, to provide the best in luxury urban living. OF STATURE Atlas stands apart, epitomising the area’s creativity and culture, energy and entrepreneurship. This is your guide to the atlas building. A INTRODUCTION CGI of the view from The Atlas Building Breathtaking B From ancient spires to ultra-modern skyscrapers, the spectacular view of London’s skyline is an everyday reminder that you’re living in one Central London INTRODUCTION of the world’s most vibrant capital cities. Liverpool Heron The The Tower 42 20 The Shard University of The St Paul’s Street Tower Gherkin Leadenhall Fenchurch Law, London Barbican Cathedral Station Building Street Moorgate CGI of The Atlas Building C THE ATLAS GUIDE TO CENTRAL LONDON LANDMARKS. INTRODUCTION NELSON’S COLUMN Completed in 1843, THE LONDON EYE stands 135 metres tall, BANK OF ENGLAND Founded in 1694, ST PAUL’S CATHEDRAL Dominating THE GHERKIN In the heart of London’s THE O2 Easily reached on the underground Nelson’s Column commemorates Admiral with a diameter of 120 metres. Designed by the Bank of England is the central bank the top of Ludgate Hill, St Paul’s Cathedral primary financial district, 30 St Mary Axe or by London’s only cable car, The O2 is an Horatio Nelson and his fall at the Battle of an impressive collection of architects, this of Britain and has influenced the structure is the City of London’s highest point. -

Annual Report 2019 Trust for London, London’S Poverty Profile 2020

CRIPPLEGATE FOUNDATION Annual Report and Financial Statements for the year ended 31st December 2019 Registered Charity No: 207499 13 Elliott’s Place, London N1 8HX www.cripplegate.org 1 Cripplegate Foundation Financial Statements for the year ended 31st December 2019 CONTENTS Report of the Trustee Introduction 3 A brief history of Cripplegate Foundation 4 Objectives 7 Activities and Achievements in 2019 7 Future plans 16 Structure, governance and management 18 Risk management 19 Key management personnel remuneration 19 Fundraising 19 Trustee’s Financial Review Financial results 20 Reserves policy 20 Unrestricted funds 20 Investment policy and performance 21 Reference and Administrative details 22 Trustee’s Responsibilities for Financial Statements 24 Independent Auditor’s Report 25 Statement of Financial Activities 27 Balance Sheet 28 Cash Flow Statement 29 Notes to the accounts 30 Appendices Appendix 1 – Islington Giving 2019 45 Appendix 2 – Grants awarded in 2019 46 2 Cripplegate Foundation Financial Statements for the year ended 31st December 2019 REPORT OF THE TRUSTEE Introduction In 2019 Cripplegate Foundation built on our mission of addressing poverty and inequality through its strong partnerships with residents, voluntary organisations, businesses, and funders from our area of benefit, and further afield. We continued to hone our relational approach to grant-making, and test new ways of involving the community in local decision-making. Cripplegate Foundation awarded £1,555,642 through our grants programmes, supporting voluntary organisations and providing financial support to individuals to pursue opportunities and meet urgent needs. The Foundation offers more than grants, we continue to invest in partnerships such as Islington Giving, open our offices to benefit voluntary organisations, and to host the headquarters of Help on Your Doorstep, one of the organisations we support. -

Access & Design Statement

Access & Design Statement Whitecross Estate East March 2017 JAN KATTEIN ARCHITECTS Content 2 01_Introduction & Context p. 03 Secure by design p.47 Introduction p. 04 04_Access & circulation p.48 Urban context p. 05 Access & circulation strategy p.49 Historic context p. 08 Parking strategy p.52 Heritage & conservation p. 10 05_Design Proposals p.52 Scheme overview p. 11 Design proposals p. 53 Consultation [summary] p. 13 Chequer Square & development site 6 p. 54 Pre-planning p. 14 Alleyn House p. 67 02_Site analysis p. 16 Blocks A and B & development site 2 p. 69 Site analysis p. 17 Errol Street p. 77 Public Realm - existing p. 19 Dufferin Court p. 79 Pedestrian circulation - existing p. 21 Daylight/sunlight p.81 Vehicle circulation - existing p.23 Access to open space before & after p.82 Play space/Open space p.24 06_Environment & sustainability p.83 Lighting condition - existing p.25 Environment & sustainability p.84 Specialist site investigations p.26 SuDs p.86 Archaeological assessment p.28 07_Service access p.88 03_Design strategy p.29 Site waste management plan p.89 Urban strategy p.30 Emergency vehicle access p.90 Public realm design strategy p. 31 Impact on external highway p.91 Soft landscape strategy p.32 Hard landscape strategy p.37 08_Management & maintenance p.92 Play strategy p.40 Open space management & maintenance p.93 Site furniture strategy p.41 Lighting strategy p.45 Whitecross Estate East February 2017 3 01_Introduction Introduction 4 Peabody have embarked on an ambitious project to • strategically re-organise the land around the buildings regenerate the Whitecross Estate. -

Locations 8 11 4 118 FARRINGDON ROAD 16 ALDERSGATE STREET 12 Smithfield Market: Proposed New Site of the Museum (Western

WHITECROSS STREET Keys Farringdon Station BRITTON STREET Cultural Hub City of London boundary SQUARE FINSBURY SQUARE Farringdon BEECH ST Crossrail 10 CHISWELL STREET CPR enhancement projects to be Station CHARTERHOUSE 17 9 delivered in 2017/2018 ST JOHN STREET Barbican 7 Station 6 CHARTERHOUSE STREET 1SILK7 STREET Locations 8 11 4 118 FARRINGDON ROAD 16 ALDERSGATE STREET 12 Smithfield Market: Proposed new site of the Museum (Western 1 SOUTH PLACE 5 Building) LONG LANE Barbican/ GSMD/LSO 17 Smithfield Market: Public realm around new Museum site - West MOOR LANE 2 16 3 Smithfield and West Poultry Ave WEST SMITHFIELD Moorgate 3 Public Realm around West Smithfield Rotunda WEST SMITHFIELD Bart’s Close Station 2 FINSBURY 1 St Alphage CIRCUS Gardens 15 MOORGATE Proposed 13 4 Hoarding around Crossrail East Farringdon station entrance Proposed Centre for Museum Music LONDON WALL of London LONDON WALL 19 5 Lanes around Cloth Fair HOLBORN VIADUCT 6 Within Barbican Tube Station FARRINGDON STREET City GILTSPUR STREET Thameslink North SHOE LANE 7 Pavement on the corner of Beech Street and Aldersgate Street MOORGATE NEWGATE STREET GRESHAM STREET KING EDWARD STREET KING EDWARD Guildhall 8 The roof of the entrance to Beech Street Christ’s Hospital 14 COLEMAN STREET artwork GRESHAM STREET Within Beech Street Tunnel OLD BAILEY 9 THROGMORTON STREET Space in front of Cromwell Tower St Paul’s 10 CHEAPSIDE LUDGATE FLEET STREET CIRCUS St Paul’s THREADNEEDLE ST 11 Silk Street LUDGATE HILL NEW Cathedral CHEAPSIDE City Thameslink St Paul’s lighting CHANGE Bank Bank CORNHILL Station 12 Moor Lane ST PAUL'S CHURCHYARD LOMBARD STREET NEW BRIDGE STREET NEW BRIDGE CANNON STREET Roman London Wall near the Museum and in the Barbican Estate KING WILLIAM STREET 13 QUEEN VICTORIA STREET GODLIMAN STREET Millenium Bridge; Riverside; Peter’s Hill; St Paul’s; St. -

Annual Report 2016

CRIPPLEGATE FOUNDATION Annual Report and Financial Statements for the year ended 31"December 2016 Registered Charity No: 207499 13 Elliott's Place, London N1 8HX www. cripplegate. org We transform lives for people in fslington. V/e're indeper. dent. and trusted. The money we give improves lives for local people, building a better future for us all. Cripplegate Foundation Financial Statements for the year ended 31"December 2016 CONTENTS Report of the Trustee Introduction 3 History 4 Objectives 4 Achievements 6 Future plans 16 Structure Governance and Management 16 Risk Management 18 Trustees' Financial Review Financial results 19 Reserves policy 19 Investment Policy 20 Reference and Administrative details 23 Trustees Responsibilities for Financial Statements 25 Independent Auditors' Report 26 Statement of Financial Activities 28 Balance Sheet 29 Cash Flow Statement 30 Notes to the accounts 31 Appendix 1-Islington Giving 2016 47 Appendix 2- Grants awarded to organisations and individuals 2016 48 Cripplegate Foundation Financial Statements for the year ended 31"December 2016 Introduction In 2016 Cripplegate Foundation made a significant positive impact on the lives of the people of Islington. Cripplegate Foundation provided direct financial support to those who need it most with E2,235,832 awarded to voluntary organisations and individuals through our grants programmes. In additio n we continued to: Chair Islington Giving, and invest significant staff and Governor time and resources into Islington Giving Partner with the London Borough of Islington to develop opportunities including through Islington Council's Community Chest and Residents' Support Scheme Influencepolicy by being independent and working with wider networks including l.ondon Funders Consult with local residents to learn more about the needs of people living in Islington Support local organisations in securing funding and improving organisational resilience Make rooms in our office available to our funded groups, and other organisations, for training and meeting purposes. -

Shire House Whitbread Centre Including Car Park and Service Yard

Development Management Service Planning and Development Division Environment and Regeneration PLANNING COMMITTEE REPORT Department PO Box 333 222 Upper Street LONDON N1 1YA PLANNING COMMITTEE Date: 22 nd July 2014 NON-EXEMPT Application number P2013/3257/FUL Application type Full Planning Application Ward Bunhill & Clerkenwell Listed building Grade II listed vaults lie beneath the site. The listed Whitbread Brewery lies immediately to the south of the subject site. Conservation area Within 50 metres of St Luke’s & Chiswell Street Conservation Areas Development Plan Context CS7: Bunhill and Clerkenwell Key Area Site Allocation BC31 & partly within B32 Within Employment Priority Area (General and partially within offices) Archaeoligcal Priority Area Central Activities Zone (CAZ) Central London Special Policy Area City Fringe Opportunity Area Finsbury Local Plan Policy BC8 Lamb’s Passage Development Brief 2006 Licensing Implications Restaurant / café use (A3 use class) sought for lower basement and upper basement vaults Site Address Shire House Whitbread Centre [including Car Park & Service Yard], 11 Lamb's Passage, London EC1Y 8TE. Proposal Comprehensive redevelopment of the site including the demolition of existing works building and re- development of the existing surface level car park, along with the conversion and alterations to the existing Grade II listed underground vaults to provide a mixed use development comprising of a part 4, part 8 storey building providing 38 residential units (19 affordable, 19 market rate) (Class C3), a 61 bedroom hotel (Class C1), office floor-space (Class B1a), restaurant (Class A3), retail (Class A1) and gym (Class D1), along with the creation of new public realm, associated landscaping and alterations to the existing access arrangements. -

149-157 Whitecross Street, Islington, London, EC1Y 8JL

Town & Country Planning Act 1990 Planning (Listed Building and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 Planning Policy Statement 5: 2010 149-157 Whitecross Street, Islington, London, EC1Y 8JL HISTORICAL REPORT December 2011 By Stacey Sykes, BA Hons Arch Cons, for and on behalf of Norton Mayfield Architects LLP 149-157 Whitecross Street, Islington, London HISTORICAL REPORT December 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Methodology Statement ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2.1 Literature and Documentary Research Review ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2.2 Building Survey ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2.3 Conservation Area Field Review ................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2.4 Previous Experience .................................................................................................................................................... -

Local Guide Computer Generated Image of Roman House

local guide Computer Generated Image of Roman House Roman House is at the heart of the City restaurants offer an international most historic part of London: The City. menu and as for shopping, all the world’s It has long been London’s financial nerve leading brands are available. The Square centre, but today it is also an exciting Mile also takes centre stage for arts and residential location, where the life of culture and at Roman House some of the capital can be enjoyed to the full. the country’s most respected venues are on the doorstep. All are waiting to be discovered. LOCAL GUIDE / ROMAN HOUSE / 3 The Gherkin MONUMENT Barbican St. Paul’s Heron Tower 42 Tower Bridge Bank The Shard BARBICAN Tower Moorgate TATE stock MODERN exchange Computer enhanced aerial photograph of Roman House and the London skyline 4 / ROMAN HOUSE / LOCAL GUIDE LOCAL GUIDE / ROMAN HOUSE / 5 Its central position in the heart of the Many of the locations marked on key to map City, means that Roman House is close this map are just a short walk from to everything you might need for work, Roman House, putting the City’s finest leisure, education, culture and travel. attractions and places of business within easy reach. Parks & green spaces .........8 SHOPPING ....................20 33 Leadenhall Market .....................20 1 St. Alphage Gardens .....................8 2 The Barbican ..........................8 34 Spitalfields Market .....................21 CI 3 35 Old Spitalfields Market .................21 TY Noble St. Gardens ......................9 RO 36 15 AD 4 Smithfield Market .....................21 Postman’s Park. 9 G A 501 5 37 One New Change.