A Nonlinear History of Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward a Large Bandwidth Photonic Correlator for Infrared Heterodyne Interferometry a first Laboratory Proof of Concept

A&A 639, A53 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201937368 & c G. Bourdarot et al. 2020 Astrophysics Toward a large bandwidth photonic correlator for infrared heterodyne interferometry A first laboratory proof of concept G. Bourdarot1,2, H. Guillet de Chatellus2, and J-P. Berger1 1 Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, 38000 Grenoble, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, LIPHY, 38000 Grenoble, France Received 19 December 2019 / Accepted 17 May 2020 ABSTRACT Context. Infrared heterodyne interferometry has been proposed as a practical alternative for recombining a large number of telescopes over kilometric baselines in the mid-infrared. However, the current limited correlation capacities impose strong restrictions on the sen- sitivity of this appealing technique. Aims. In this paper, we propose to address the problem of transport and correlation of wide-bandwidth signals over kilometric dis- tances by introducing photonic processing in infrared heterodyne interferometry. Methods. We describe the architecture of a photonic double-sideband correlator for two telescopes, along with the experimental demonstration of this concept on a proof-of-principle test bed. Results. We demonstrate the a posteriori correlation of two infrared signals previously generated on a two-telescope simulator in a double-sideband photonic correlator. A degradation of the signal-to-noise ratio of 13%, equivalent to a noise factor NF = 1:15, is obtained through the correlator, and the temporal coherence properties of our input signals are retrieved from these measurements. Conclusions. Our results demonstrate that photonic processing can be used to correlate heterodyne signals with a potentially large increase of detection bandwidth. -

Army Radio Communication in the Great War Keith R Thrower, OBE

Army radio communication in the Great War Keith R Thrower, OBE Introduction Prior to the outbreak of WW1 in August 1914 many of the techniques to be used in later years for radio communications had already been invented, although most were still at an early stage of practical application. Radio transmitters at that time were predominantly using spark discharge from a high voltage induction coil, which created a series of damped oscillations in an associated tuned circuit at the rate of the spark discharge. The transmitted signal was noisy and rich in harmonics and spread widely over the radio spectrum. The ideal transmission was a continuous wave (CW) and there were three methods for producing this: 1. From an HF alternator, the practical design of which was made by the US General Electric engineer Ernst Alexanderson, initially based on a specification by Reginald Fessenden. These alternators were primarily intended for high-power, long-wave transmission and not suitable for use on the battlefield. 2. Arc generator, the practical form of which was invented by Valdemar Poulsen in 1902. Again the transmitters were high power and not suitable for battlefield use. 3. Valve oscillator, which was invented by the German engineer, Alexander Meissner, and patented in April 1913. Several important circuits using valves had been produced by 1914. These include: (a) the heterodyne, an oscillator circuit used to mix with an incoming continuous wave signal and beat it down to an audible note; (b) the detector, to extract the audio signal from the high frequency carrier; (c) the amplifier, both for the incoming high frequency signal and the detected audio or the beat signal from the heterodyne receiver; (d) regenerative feedback from the output of the detector or RF amplifier to its input, which had the effect of sharpening the tuning and increasing the amplification. -

A Brief History of Radio Broadcasting in Africa

A Brief History of Radio Broadcasting in Africa Radio is by far the dominant and most important mass medium in Africa. Its flexibility, low cost, and oral character meet Africa's situation very well. Yet radio is less developed in Africa than it is anywhere else. There are relatively few radio stations in each of Africa's 53 nations and fewer radio sets per head of population than anywhere else in the world. Radio remains the top medium in terms of the number of people that it reaches. Even though television has shown considerable growth (especially in the 1990s) and despite a widespread liberalization of the press over the same period, radio still outstrips both television and the press in reaching most people on the continent. The main exceptions to this ate in the far south, in South Africa, where television and the press are both very strong, and in the Arab north, where television is now the dominant medium. South of the Sahara and north of the Limpopo River, radio remains dominant at the start of the 21St century. The internet is developing fast, mainly in urban areas, but its growth is slowed considerably by the very low level of development of telephone systems. There is much variation between African countries in access to and use of radio. The weekly reach of radio ranges from about 50 percent of adults in the poorer countries to virtually everyone in the more developed ones. But even in some poor countries the reach of radio can be very high. In Tanzania, for example, nearly nine out of ten adults listen to radio in an average week. -

The Stage Is Set

The Stage Is Set: Developments before 1900 Leading to Practical Wireless Communication Darrel T. Emerson National Radio Astronomy Observatory1, 949 N. Cherry Avenue, Tucson, AZ 85721 In 1909, Guglielmo Marconi and Carl Ferdinand Braun were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics "in recognition of their contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy." In the Nobel Prize Presentation Speech by the President of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences [1], tribute was first paid to the earlier theorists and experimentalists. “It was Faraday with his unique penetrating power of mind, who first suspected a close connection between the phenomena of light and electricity, and it was Maxwell who transformed his bold concepts and thoughts into mathematical language, and finally, it was Hertz who through his classical experiments showed that the new ideas as to the nature of electricity and light had a real basis in fact.” These and many other scientists set the stage for the rapid development of wireless communication starting in the last decade of the 19th century. I. INTRODUCTION A key factor in the development of wireless communication, as opposed to pure research into the science of electromagnetic waves and phenomena, was simply the motivation to make it work. More than anyone else, Marconi was to provide that. However, for the possibility of wireless communication to be treated as a serious possibility in the first place and for it to be able to develop, there had to be an adequate theoretical and technological background. Electromagnetic theory, itself based on earlier experiment and theory, had to be sufficiently developed that 1. -

History of Radio Broadcasting in Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1963 History of radio broadcasting in Montana Ron P. Richards The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Richards, Ron P., "History of radio broadcasting in Montana" (1963). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5869. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5869 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF RADIO BROADCASTING IN MONTANA ty RON P. RICHARDS B. A. in Journalism Montana State University, 1959 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1963 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number; EP36670 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Oiuartation PVUithing UMI EP36670 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Lecture 25 Demodulation and the Superheterodyne Receiver EE445-10

EE447 Lecture 6 Lecture 25 Demodulation and the Superheterodyne Receiver EE445-10 HW7;5-4,5-7,5-13a-d,5-23,5-31 Due next Monday, 29th 1 Figure 4–29 Superheterodyne receiver. m(t) 2 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. 0-13-142492-0 1 EE447 Lecture 6 Synchronous Demodulation s(t) LPF m(t) 2Cos(2πfct) •Only method for DSB-SC, USB-SC, LSB-SC •AM with carrier •Envelope Detection – Input SNR >~10 dB required •Synchronous Detection – (no threshold effect) •Note the 2 on the LO normalizes the output amplitude 3 Figure 4–24 PLL used for coherent detection of AM. 4 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. 0-13-142492-0 2 EE447 Lecture 6 Envelope Detector C • Ac • (1+ a • m(t)) Where C is a constant C • Ac • a • m(t)) 5 Envelope Detector Distortion Hi Frequency m(t) Slope overload IF Frequency Present in Output signal 6 3 EE447 Lecture 6 Superheterodyne Receiver EE445-09 7 8 4 EE447 Lecture 6 9 Super-Heterodyne AM Receiver 10 5 EE447 Lecture 6 Super-Heterodyne AM Receiver 11 RF Filter • Provides Image Rejection fimage=fLO+fif • Reduces amplitude of interfering signals far from the carrier frequency • Reduces the amount of LO signal that radiates from the Antenna stop 2/22 12 6 EE447 Lecture 6 Figure 4–30 Spectra of signals and transfer function of an RF amplifier in a superheterodyne receiver. 13 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. -

Basic Electronics

14 Basic Electronics In this chapter, we lead you through a study of the basics of electronics. After completing the chapter, you should be able to Understand the physical structure of semiconductors. Understand the essence of the diode function. Understand the operation of diodes. Realize the applications of diodes and their use in the design of rectifiers. Understand the physical operation of bipolar junction transistors. Realize the applications of bipolar junction transistors. Understand the physical operation of field-effect transistors. Realize the application of field-effect transistors. Perform rapid analysis of transistor circuits. REFERENCES 1. Giorgio Rizzoni, Principles and Applications of Electrical Engineering, McGraw Hill, 2003. 2. J. R. Cogdel, Foundations of Electronics, Prentice Hall, 1999. 3. Donald A., Neaman, Electronic Circuit Analysis and Design, McGraw Hill, 2001. 4. Sedra/Smith, Microelectronic Circuits, Oxford, 1998. 1 Basic Electronics 2 14.1 INTRODUCTION Electronics is one of the most important fields in existence today. It has greatly influenced everything since early 1900s. Everyone nowadays realize the impact of electronics on our daily life. Table 14-1 shows many important areas with tremendous impact of electronics. Table 14-1 Various Application Areas of Electronics Area Examples of Applications Automotives Electronic ignition system, antiskid braking system, automatic suspension adjustment, performance optimization. Aerospace Airplane controls, spacecrafts, space missiles. Telecommunications Radio, television, telephones, mobile and cellular communications, satellite communications, military communications. Computers Personal computers, mainframe computers, supercomputers, calculators, microprocessors. Instrumentation Measurement equipment such as meters and oscilloscopes, medical equipment such as MRI, X- ray machines, etc. Microelectronics Microelectronic circuits, microelectromechanical systems. Power electronics Converters, Radar Air traffic control, security systems, military systems, police traffic radars. -

1999-2017 INDEX This Index Covers Tube Collector Through August 2017, the TCA "Data Cache" DVD- ROM Set, and the TCA Special Publications: No

1999-2017 INDEX This index covers Tube Collector through August 2017, the TCA "Data Cache" DVD- ROM set, and the TCA Special Publications: No. 1 Manhattan College Vacuum Tube Museum - List of Displays .........................1999 No. 2 Triodes in Radar: The Early VHF Era ...............................................................2000 No. 3 Auction Results ....................................................................................................2001 No. 4 A Tribute to George Clark, with audio CD ........................................................2002 No. 5 J. B. Johnson and the 224A CRT.........................................................................2003 No. 6 McCandless and the Audion, with audio CD......................................................2003 No. 7 AWA Tube Collector Group Fact Sheet, Vols. 1-6 ...........................................2004 No. 8 Vacuum Tubes in Telephone Work.....................................................................2004 No. 9 Origins of the Vacuum Tube, with audio CD.....................................................2005 No. 10 Early Tube Development at GE...........................................................................2005 No. 11 Thermionic Miscellany.........................................................................................2006 No. 12 RCA Master Tube Sales Plan, 1950....................................................................2006 No. 13 GE Tungar Bulb Data Manual................................................................. -

Thyristors.Pdf

THYRISTORS Electronic Devices, 9th edition © 2012 Pearson Education. Upper Saddle River, NJ, 07458. Thomas L. Floyd All rights reserved. Thyristors Thyristors are a class of semiconductor devices characterized by 4-layers of alternating p and n material. Four-layer devices act as either open or closed switches; for this reason, they are most frequently used in control applications. Some thyristors and their symbols are (a) 4-layer diode (b) SCR (c) Diac (d) Triac (e) SCS Electronic Devices, 9th edition © 2012 Pearson Education. Upper Saddle River, NJ, 07458. Thomas L. Floyd All rights reserved. The Four-Layer Diode The 4-layer diode (or Shockley diode) is a type of thyristor that acts something like an ordinary diode but conducts in the forward direction only after a certain anode to cathode voltage called the forward-breakover voltage is reached. The basic construction of a 4-layer diode and its schematic symbol are shown The 4-layer diode has two leads, labeled the anode (A) and the Anode (A) A cathode (K). p 1 n The symbol reminds you that it acts 2 p like a diode. It does not conduct 3 when it is reverse-biased. n Cathode (K) K Electronic Devices, 9th edition © 2012 Pearson Education. Upper Saddle River, NJ, 07458. Thomas L. Floyd All rights reserved. The Four-Layer Diode The concept of 4-layer devices is usually shown as an equivalent circuit of a pnp and an npn transistor. Ideally, these devices would not conduct, but when forward biased, if there is sufficient leakage current in the upper pnp device, it can act as base current to the lower npn device causing it to conduct and bringing both transistors into saturation. -

HP 423A Crystal Detector

Errata Title & Document Type: 423A and 8470A Crystal Detector Operating and Service Manual Manual Part Number: 00423-90001 Revision Date: July 1976 About this Manual We’ve added this manual to the Agilent website in an effort to help you support your product. This manual provides the best information we could find. It may be incomplete or contain dated information, and the scan quality may not be ideal. If we find a better copy in the future, we will add it to the Agilent website. HP References in this Manual This manual may contain references to HP or Hewlett-Packard. Please note that Hewlett- Packard's former test and measurement, life sciences, and chemical analysis businesses are now part of Agilent Technologies. The HP XXXX referred to in this document is now the Agilent XXXX. For example, model number HP8648A is now model number Agilent 8648A. We have made no changes to this manual copy. Support for Your Product Agilent no longer sells or supports this product. You will find any other available product information on the Agilent Test & Measurement website: www.agilent.com Search for the model number of this product, and the resulting product page will guide you to any available information. Our service centers may be able to perform calibration if no repair parts are needed, but no other support from Agilent is available. OPERATING AND SERVICE MANUAL - I 423A 8470A CRYSTAL DETECTOR HEWLETT~PACKARD Plint.d: JUtY 191& e H.",len Packard Co. \910 1 " • .' • I .... ,. ", - \, . '. ~ ~.. ". ." , .' " . ..... " 'I. "",:,. • ' Page 2 i\lodel ·123A/8470A 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 10. -

Crystal Radio Set Systems: Design, Measurement, and Improvement Volume II a Web Book by Ben Tongue

Crystal Radio Set Systems: Design, Measurement, and Improvement Volume II A web book by Ben Tongue First published: 10 Jul 1999; Revised: 01/06/10 i NOTES: ii 185 PREFACE Note: An easy way to use a DVM ohmmeter to check if a ferrite is made of MnZn of NiZn material is to place the leads of the ohmmeter on a bare part of the test ferrite and read the The main purpose of these Articles is to show how resistance. The resistance of NiZn will be so high that the Engineering Principles may be applied to the design of crystal ohmmeter will show an open circuit. If the ferrite is of the radios. Measurement techniques and actual measurements are MnZn type, the ohmmeter will show a reading. The reading described. They relate to selectivity, sensitivity, inductor (coil) was about 100k ohms on the ferrite rods used here. and capacitor Q (quality factor), impedance matching, the diode SPICE parameters saturation current and ideality factor, #29 Published: 10/07/2006; Revised: 01/07/08 audio transformer characteristics, earphone and antenna to ground system parameters. The design of some crystal radios that embody these principles are shown, along with performance measurements. Some original technical concepts such as the linear-to-square-law crossover point of a diode detector, contra-wound inductors and the 'benny' are presented. Please note: If any terms or concepts used here are unclear or obscure, please check out Article # 00 for possible explanations. If there still is a problem, e-mail me and I'll try to assist (Use the link below to the Front Page for my Email address). -

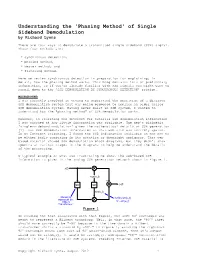

Of Single Sideband Demodulation by Richard Lyons

Understanding the 'Phasing Method' of Single Sideband Demodulation by Richard Lyons There are four ways to demodulate a transmitted single sideband (SSB) signal. Those four methods are: • synchronous detection, • phasing method, • Weaver method, and • filtering method. Here we review synchronous detection in preparation for explaining, in detail, how the phasing method works. This blog contains lots of preliminary information, so if you're already familiar with SSB signals you might want to scroll down to the 'SSB DEMODULATION BY SYNCHRONOUS DETECTION' section. BACKGROUND I was recently involved in trying to understand the operation of a discrete SSB demodulation system that was being proposed to replace an older analog SSB demodulation system. Having never built an SSB system, I wanted to understand how the "phasing method" of SSB demodulation works. However, in searching the Internet for tutorial SSB demodulation information I was shocked at how little information was available. The web's wikipedia 'single-sideband modulation' gives the mathematical details of SSB generation [1]. But SSB demodulation information at that web site was terribly sparse. In my Internet searching, I found the SSB information available on the net to be either badly confusing in its notation or downright ambiguous. That web- based material showed SSB demodulation block diagrams, but they didn't show spectra at various stages in the diagrams to help me understand the details of the processing. A typical example of what was frustrating me about the web-based SSB information is given in the analog SSB generation network shown in Figure 1. x(t) cos(ωct) + 90o 90o y(t) – sin(ωct) Meant to Is this sin(ω t) represent the c Hilbert or –sin(ωct) Transformer.