Joan Semmeljoan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond. -

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism by Matthew Purvis A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020, Matthew Purvis i Abstract This dissertation concerns the relation between eroticism and nationalism in the work of a set of English Canadian artists in the mid-1960s-70s, namely John Boyle, Greg Curnoe, and Joyce Wieland. It contends that within their bodies of work there are ways of imagining nationalism and eroticism that are often formally or conceptually interrelated, either by strategy or figuration, and at times indistinguishable. This was evident in the content of their work, in the models that they established for interpreting it and present in more and less overt forms in some of the ways of imagining an English Canadian nationalism that surrounded them. The dissertation contextualizes the three artists in the terms of erotic art prevalent in the twentieth century and makes a case for them as part of a uniquely Canadian mode of decadence. Constructing my case largely from the published and unpublished writing of the three subjects and how these played against their reception, I have attempted to elaborate their artistic models and processes, as well as their understandings of eroticism and nationalism, situating them within the discourses on English Canadian nationalism and its potentially morbid prospects. Rather than treating this as a primarily cultural or socio-political issue, it is treated as both an epistemic and formal one. -

'Wack!' the Art of Feminism As It First Took Shape

Friday, March 9, The New York Times 'Wack!' The Art of Feminism as It First Took Shape By HOLLAND COTTER. 2007 Opening of the first-ever museum show of feminist art at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Holland Cotter’s feature-length review was illustrated by four works, including Mlle Bourgeoise Noire. LOS ANGELES, March 4 — If you’ve held your breath for 40 years waiting for something to happen, your feelings can’t help being mixed when it finally does: “At last!” but also “Not enough.” That’s bound to be one reaction to “Wack! Art and the Feminist Revolution” at the Museum of Contemporary Art here, the first major museum show of early feminist work. Let me be clear: The show is a thrill, rich and sustained. Just by existing, it makes history. But like any history, once written, it is also an artifact, a frozen and partial monument to an art movement that was never a movement, or rather was many movements, or impulses, vibrant and vexingly contradictory. One thing is certain: Feminist art, which emerged in the 1960s with the women’s movement, is the formative art of the last four decades. Scan the most innovative work, by both men and women, done during that time, and you’ll find feminism’s activist, expansionist, pluralistic trace. Without it identity-based art, crafts-derived art, performance art and much political art would not exist in the form it does, if it existed at all. Much of what we call postmodern art has feminist art at its source. -

Marilyn Minter's Politically Incorrect Pleasures

MARILYN MINTER’S POLITICALLY INCORRECT PLEASURES ELISSA AUTHER of Lena Dunham and Beyoncé, gaze as much as they invite it. Furthermore, her interest in IN THE AGE it is hard to imagine that only two physical flaws and soiled elegance undermines the illusions of or three decades ago, progressive- minded people derided the perfection normally promoted by the glossy commercial image. free display of female sexuality.1 But that is exactly the unfriendly Minter often reveals much more than we want to see. It is in the context in which Marilyn Minter first offered up her body of collision of these two powerful aesthetic forces, the beautiful technically virtuosic and openly erotic paintings. Minter’s and the grotesque—what Minter has described as the “path- career- long exploration of beauty, desire, and pleasure- in- ology of glamour”5—that the artist presents her compelling looking has occupied, at best, an uneasy place within feminist visual investigation into the nature of our passions and fantasies, art history and criticism. Her painted and photographic appro- finding them unruly and highly resistant to ideological correction. priations of pornographic imagery, physical flaws, and high From Minter’s earliest forays as an artist, the female body fashion never function as easy, straightforward critiques of has been the primary vehicle through which she has addressed patriarchal culture. As one critic has remarked, “It is difficult to issues of beauty and desire. Her series of black- and- white tell if Marilyn Minter’s subjects are meant to make viewers photographs of her mother (cats. 1–5), shot in 1969, when uncomfortable—or turn them on.”2 That Minter’s work insists she was still an undergraduate at the University of Florida, on both has always been a challenge for viewers who require Gainesville, went straight to the heart of the conventions and confirmation that she is on the correct side of the political artifice of feminine beauty. -

Woman's Art Journal, Pp. 1-6.Pdf

Woman's Art Inc. Sexual Imagery in Women's Art Author(s): Joan Semmel and April Kingsley Source: Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 1980), pp. 1-6 Published by: Woman's Art Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358010 . Accessed: 31/10/2013 13:21 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Woman's Art Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Woman's Art Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 131.128.70.20 on Thu, 31 Oct 2013 13:21:39 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Sexual Imagery In Women's Art JOAN SEMMEL APRIL KINGSLEY Women's sexual art tends to stress either strong posi- skillfully referring us back to other contexts. This re- tive or strong negative aspects of their experiences. ferral to a realm of experience thought to be antithetical Feelings of victimization and anger, while sometimes to "sacred" art is characteristic of Pop art in general. expressed as masochistic fantasy, often become politically However, in the case of erotic imagery the evocation of directed, especially in contemporary works. -

Download Issue (PDF)

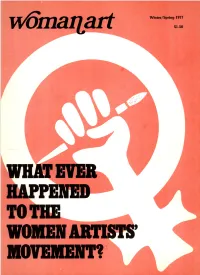

Vol. 1 No. 3 r r l S J L f J C L f f C t J I Winter/Spring 1977 AT LONG LAST —An historical view of art made by women by Miriam Schapiro page 4 DIALOGUES WITH NANCY SPERO by Carol De Pasquale page 8 THE SISTER CHAPEL —A traveling homage to heroines by Gloria Feman Orenstein page 12 'Women Artists: 1550— 1950’ ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI — Her life in art, part II by Barbara Cavaliere page 22 THE WOMEN ARTISTS’ MOVEMENT —An Assessment Interviews with June Blum, Mary Ann Gillies, Lucy Lippard, Pat Mainardi, Linda Nochlin, Ce Roser, Miriam Schapiro, Jackie Skiles, Nancy Spero, and Michelle Stuart page 26 THE VIEW FROM SONOMA by Lawrence Alloway page 40 The Sister Chapel GALLERY REVIEWS page 41 REPORTS ‘Realists Choose Realists’ and the Douglass College Library Program page 51 WOMANART MAGAZINE is published quarterly by Womanart Enterprises, 161 Prospect Park West, Brooklyn, New York 11215. Editorial submissions and all inquiries should be sent to: P. O. Box 3358, Grand Central Station, New York, N.Y. 10017. Subscription rate: $5.00 for one year. All opinions expressed are those o f the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those o f the editors. This publication is on file with the International Women’s History Archive, Special Collections Library, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60201. Permission to reprint must be secured in writing from the publishers. Copyright © Artemisia Gentileschi- Fame' Womanart Enterprises, 1977. A ll rights reserved. AT LONG LAST AN HISTORICAL VIEW OF ART MADE BY WOMEN by Miriam Schapiro Giovanna Garzoni, Still Life with Birds and Fruit, ca. -

Portraits” Proof

Vol. 2 No. 1 wdmaqartrrVlliftAIIUA l Fall 1977 OUT OF THE MAINSTREAM Two artists' attitudes about survival outside of New York City by Janet Heit page 4 19th CENTURY AMERICAN PRINTMAKERS A neglected group of women is revealed to have filled roles from colorist to Currier & Ives mainstay by Ann-Sargent Wooster page 6 INTERVIEW WITH BETTY PARSONS The septuagenarian artist and dealer speaks frankly about her relationship to the art world, its women, and the abstract expressionists by Helene Aylon .............................................................................. pag e 10 19th c. Printmakers MARIA VAN OOSTERWUCK This 17th century Dutch flower painter was commissioned and revered by the courts of Europe, but has since been forgotten by Rosa Lindenburg ........................................................................pag e ^ 6 STRANGERS WHEN WE MEET A 'how-to' portrait book reveals societal attitudes toward women by Lawrence A llo w a y ..................................................................... pag e 21 GALLERY REVIEWS ............................................................................page 22 EVA HESSE Combined review of Lucy Lippard's book and a recent retrospective exhibition by Jill Dunbar ...................................................................................p a g e 33 REPORTS Artists Support Women's Rights Day Activities, Bridgeport Artists' Studio—The Factory ........................................ p a g e 34 Betty Parsons W OMAN* ART*WORLD News items of interest page 35 Cover: Betty Parsons. Photo by Alexander Liberman. WOMANARTMAGAZINE is published quarterly by Womanart Enterprises. 161 Prospect.Park West, Brooklyn. New York 11215. Editorial submissions and all inquiries should be sent to: P.O. Box 3358, Grand Central Station. New York. N.Y. 10017. Subscription rate: $5.00 fo r one year. Application to mail at second class postage rates pending in Brooklyn. N. Y. -

Hanne Darboven and the Trace of the Artist's Hand

Mind Circles: on conceptual deliberation −Hanne Darboven and the trace of the artist's hand A JESPERSEN PhD 2015 Mind Circles: on conceptual deliberation −Hanne Darboven and the trace of the artist's hand Andrea Jespersen MA (RCA) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences May 2015 2 Abstract The phrase ‘de-materialisation of the art object’ has frequently assumed the mistaken role of a universal definition for original conceptual art. My art practice has prompted me to reconsider the history of the term de- materialisation to research another type of conceptual art, one that embraces materiality and incorporates cerebral handmade methods, as evidenced in the practice of the German artist Hanne Darboven. This thesis will establish that materiality and the handmade – the subjective – was embraced by certain original conceptual artists. Furthermore, it argues that within art practices that use concepts, the cerebral handmade can function to prolong the artist’s conceptual deliberation and likewise instigate a nonlinear conscious inquisitiveness in the viewer. My practice-based methodologies for this research involved analogue photography, drawing, an artist residency, exhibition making, publishing, artist talks and interdisciplinary collaborations with various practices of knowledge. The thesis reconsiders the definition of conceptual art through an analysis of the original conceptual art practices initiated in New York City during the 1960s and 1970s that utilised handmade methods. I review and reflect upon the status of the cerebral handmade in conceptual art through a close study of the work of Hanne Darboven, whose work since 1968 has been regularly included in conceptual art exhibitions. -

MARTHA NILSSON EDELHEIT Selected Vitae

MARTHA NILSSON EDELHEIT Selected Vitae Born in New York, NY, USA Lives and works in Sweden (since 1993) Selected Solo Exhibitions 2014 Artifact Gallery, New York, NY 2009 Piteå Konsthall, Piteå, Sweden 2008 SOHO20 Chelsea Gallery, New York, NY 2007 Villa Landes, Kimito, Finland SARKA Museum, Loimaa, Finland Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland 2004 Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland Galleri Cupido, Stockholm, Sweden 2003 Konstpaus, Ekerö, Sweden 2002 Galleri Strömbom, Uppsala, Sweden 2001 Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm, Sweden 2000 Medborgarhuset, Smedstorp, Sweden 1999 Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland Galleri Hovet, Gamla Ishovet, Stockholm, Sweden 1998 Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm, Sweden 1996 Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland 1992 Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland 1991 SOHO20 Gallery, New York, NY Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland 1988 SOHO20 Gallery, New York, NY 1987 Atelier 2000, Vienna, Austria Galerie Carinthia, Klagenfurt, Austria 1986 SOHO20 Gallery, New York, NY 1984 Women’s Interart Center, New York, NY A.I.R. Gallery, New York, NY 1982 Rutgers University, Douglass Library, NJ 1975 Wilson College, Chambersburg, PA 1974 Evanston Art Center, Evanston, IL 1973 Artists Space, New York, NY 1966 Byron Gallery, New York, NY 1964 OK Harris, Provincetown, MA 1961 Judson Gallery, New York, NY 1960 Reuben Gallery, New York, NY 1 MARTHA NILSSON EDELHEIT Selected Vitae Selected Group Exhibitions 2017 Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965, Grey Gallery, New York University, New York, NY 2017 Annual Group Exhibition, -

Women's Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award

C13831W1_C13831W1 1/31/13 12:31 PM Page 1 WOMEN’S CAUCUS FOR ART Honor Awards For Lifetime Achievement In The Visual Arts Tina Dunkley Artis Lane Susana Torruella Leval Joan Semmel C13831W1_C13831W1 1/31/13 12:31 PM Page 2 C13831W1_C13831W1 1/31/13 12:31 PM Page 3 Thursday, February 14th New York, NY Introduction Priscilla H. Otani WCA National Board President, 2012–14 Presentation of Lifetime Achievement Awards Tina Dunkley Essay by Jerry Cullum. Presentation by Brenda Thompson. Artis Lane Essay and Presentation by Jarvis DuBois. Susana Torruella Leval Essay by Anne Swartz. Presentation by Susan Del Valle. Joan Semmel Essay by Gail Levin. Presentation by Joan Marter. Presentation of President’s Art & Activism Award Leanne Stella Presentation by Priscilla H. Otani. C13831W1_C13831W1 1/31/13 12:31 PM Page 4 LTA Awards—Foreword and Acknowledgments In 2013, we celebrate the achievements of four highly at El Museo del Barrio and soon to be director of the Sugar creative individuals: Tina Dunkley, director of the Clark Hill Children’s Museum of Art & Storytelling in Harlem, will Atlanta University Art Galleries; sculptor Artis Lane; introduce Leval at the ceremony. Jerry Cullum, freelance Susana T. Leval, Director Emerita of El Museo del Barrio; curator and critic, who for many years served in various and painter Joan Semmel. Each woman has made a unique editorial positions at Art Papers, has written an engaging contribution to the arts in America. Through sustained and essay about Dunkley’s work, and Brenda Thompson, insightful curatorial practice, two of this year’s honorees collector of African American art of the diaspora, will have brought national attention to the significant present her at the awards ceremony. -

WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution March 4Th 2007 to July 16Th 2007 52 North Central Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90013

mercredi 17 mars 2010 17:47 Subject: Newsletter Date: lundi 12 février 2007 22:03 From: Christine Renee <[email protected]> To: Orlan <[email protected]> ! WACK! Art and the feminist revolution March 4th 2007 to July 16th 2007 52 North Central Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90013 The first comprehensive, historical exhibition to examine the international foundations and legacy of feminist art, WACK! focuses on 1965 to 1980, the crucial period during which the majority of feminist activism and art-making occurred in North America. The exhibition includes the work of approximately 100 artists from the United States, Central and Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Comprising work in a broad range of media, including painting, sculpture, photography, film, video and performance art, the exhibition is organized around themes based on media, geography, formal concerns, and collective aesthetic and political impulses. The exhibition is curated by MOCA Curator Connie Butler and is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue Magdalena Abakanowicz - Marina Abramovic - Carla Accardi - Chantal Akerman - Helena Almeida - Sonia Andrade - Eleanor Antin - Judith F. Baca - Mary Bauermeister - Lynda Benglis Camille Billops - Dara Birnbaum - Louise Bourgeois - Theresa Hak Kyung Cha - Judy Chicago - Ursula Reuter Christiansen - Lygia Clark - Tee Corinne - Sheila Levrant de Bretteville - Iole de Freitas- Niki de Saint Phalle, Jean Tinguely and Per Olof Utvedt - Jay DeFeo - Assia Djebar - Disband - Rita Donagh - Kirsten Dufour -

Alice Neel's American Portrait Gallery

Pictures of People Pictures of People Alice Neel’s American Portrait Gallery Pamela Allara Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England Hanover and London Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England, Hanover, NH 03755 © 1998 by the Trustees of Brandeis University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN for paperback edition: 978–1–61168–513–8 ISBN for ebook edition: 978–1–61168–049–2 library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Allara, Pamela. Pictures of people : Alice Neel’s American portrait gallery / by Pamela Allara. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–87451–837–7 1. Neel, Alice, 1900– —Criticism and interpretation. 2. United States— Biography—Portraits. I. Neel, Alice, 1900– . II. Title. ND1329.N36A9 1998 97–18403 759.13—DC21 Throughout this book, “Estate of Alice Neel” includes works in the collections of Richard Neel, Hartley S. Neel, their respective families, and Neel Arts, Inc. 5432 NOTE TO EREADERS As electronic reproduction rights are unavailable for images appearing in this book’s print edition, no illustrations are included in this ebook. Readers interested in seeing the art referenced here should either consult this book’s print edition or visit an online resource such as aliceneel.com or artstor.org. vi CONTENTS illustrations included in the print edition ix acknowledgments xv Introduction: The Portrait Gallery xvii PART I: THE SUBJECTS OF THE ARTIST Chapter 1: The Creation (of a) Myth 3 Chapter 2: From Portraiture