Dimensioning and Tolerancing, Section 6, Drafting Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson 3: Rectangles Inscribed in Circles

NYS COMMON CORE MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM Lesson 3 M5 GEOMETRY Lesson 3: Rectangles Inscribed in Circles Student Outcomes . Inscribe a rectangle in a circle. Understand the symmetries of inscribed rectangles across a diameter. Lesson Notes Have students use a compass and straightedge to locate the center of the circle provided. If necessary, remind students of their work in Module 1 on constructing a perpendicular to a segment and of their work in Lesson 1 in this module on Thales’ theorem. Standards addressed with this lesson are G-C.A.2 and G-C.A.3. Students should be made aware that figures are not drawn to scale. Classwork Scaffolding: Opening Exercise (9 minutes) Display steps to construct a perpendicular line at a point. Students follow the steps provided and use a compass and straightedge to find the center of a circle. This exercise reminds students about constructions previously . Draw a segment through the studied that are needed in this lesson and later in this module. point, and, using a compass, mark a point equidistant on Opening Exercise each side of the point. Using only a compass and straightedge, find the location of the center of the circle below. Label the endpoints of the Follow the steps provided. segment 퐴 and 퐵. Draw chord 푨푩̅̅̅̅. Draw circle 퐴 with center 퐴 . Construct a chord perpendicular to 푨푩̅̅̅̅ at and radius ̅퐴퐵̅̅̅. endpoint 푩. Draw circle 퐵 with center 퐵 . Mark the point of intersection of the perpendicular chord and the circle as point and radius ̅퐵퐴̅̅̅. 푪. Label the points of intersection . -

Squaring the Circle a Case Study in the History of Mathematics the Problem

Squaring the Circle A Case Study in the History of Mathematics The Problem Using only a compass and straightedge, construct for any given circle, a square with the same area as the circle. The general problem of constructing a square with the same area as a given figure is known as the Quadrature of that figure. So, we seek a quadrature of the circle. The Answer It has been known since 1822 that the quadrature of a circle with straightedge and compass is impossible. Notes: First of all we are not saying that a square of equal area does not exist. If the circle has area A, then a square with side √A clearly has the same area. Secondly, we are not saying that a quadrature of a circle is impossible, since it is possible, but not under the restriction of using only a straightedge and compass. Precursors It has been written, in many places, that the quadrature problem appears in one of the earliest extant mathematical sources, the Rhind Papyrus (~ 1650 B.C.). This is not really an accurate statement. If one means by the “quadrature of the circle” simply a quadrature by any means, then one is just asking for the determination of the area of a circle. This problem does appear in the Rhind Papyrus, but I consider it as just a precursor to the construction problem we are examining. The Rhind Papyrus The papyrus was found in Thebes (Luxor) in the ruins of a small building near the Ramesseum.1 It was purchased in 1858 in Egypt by the Scottish Egyptologist A. -

And Are Congruent Chords, So the Corresponding Arcs RS and ST Are Congruent

9-3 Arcs and Chords ALGEBRA Find the value of x. 3. SOLUTION: 1. In the same circle or in congruent circles, two minor SOLUTION: arcs are congruent if and only if their corresponding Arc ST is a minor arc, so m(arc ST) is equal to the chords are congruent. Since m(arc AB) = m(arc CD) measure of its related central angle or 93. = 127, arc AB arc CD and . and are congruent chords, so the corresponding arcs RS and ST are congruent. m(arc RS) = m(arc ST) and by substitution, x = 93. ANSWER: 93 ANSWER: 3 In , JK = 10 and . Find each measure. Round to the nearest hundredth. 2. SOLUTION: Since HG = 4 and FG = 4, and are 4. congruent chords and the corresponding arcs HG and FG are congruent. SOLUTION: m(arc HG) = m(arc FG) = x Radius is perpendicular to chord . So, by Arc HG, arc GF, and arc FH are adjacent arcs that Theorem 10.3, bisects arc JKL. Therefore, m(arc form the circle, so the sum of their measures is 360. JL) = m(arc LK). By substitution, m(arc JL) = or 67. ANSWER: 67 ANSWER: 70 eSolutions Manual - Powered by Cognero Page 1 9-3 Arcs and Chords 5. PQ ALGEBRA Find the value of x. SOLUTION: Draw radius and create right triangle PJQ. PM = 6 and since all radii of a circle are congruent, PJ = 6. Since the radius is perpendicular to , bisects by Theorem 10.3. So, JQ = (10) or 5. 7. Use the Pythagorean Theorem to find PQ. -

Squaring the Circle in Elliptic Geometry

Rose-Hulman Undergraduate Mathematics Journal Volume 18 Issue 2 Article 1 Squaring the Circle in Elliptic Geometry Noah Davis Aquinas College Kyle Jansens Aquinas College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rhumj Recommended Citation Davis, Noah and Jansens, Kyle (2017) "Squaring the Circle in Elliptic Geometry," Rose-Hulman Undergraduate Mathematics Journal: Vol. 18 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rhumj/vol18/iss2/1 Rose- Hulman Undergraduate Mathematics Journal squaring the circle in elliptic geometry Noah Davis a Kyle Jansensb Volume 18, No. 2, Fall 2017 Sponsored by Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Department of Mathematics Terre Haute, IN 47803 a [email protected] Aquinas College b scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rhumj Aquinas College Rose-Hulman Undergraduate Mathematics Journal Volume 18, No. 2, Fall 2017 squaring the circle in elliptic geometry Noah Davis Kyle Jansens Abstract. Constructing a regular quadrilateral (square) and circle of equal area was proved impossible in Euclidean geometry in 1882. Hyperbolic geometry, however, allows this construction. In this article, we complete the story, providing and proving a construction for squaring the circle in elliptic geometry. We also find the same additional requirements as the hyperbolic case: only certain angle sizes work for the squares and only certain radius sizes work for the circles; and the square and circle constructions do not rely on each other. Acknowledgements: We thank the Mohler-Thompson Program for supporting our work in summer 2014. Page 2 RHIT Undergrad. Math. J., Vol. 18, No. 2 1 Introduction In the Rose-Hulman Undergraduate Math Journal, 15 1 2014, Noah Davis demonstrated the construction of a hyperbolic circle and hyperbolic square in the Poincar´edisk [1]. -

20. Geometry of the Circle (SC)

20. GEOMETRY OF THE CIRCLE PARTS OF THE CIRCLE Segments When we speak of a circle we may be referring to the plane figure itself or the boundary of the shape, called the circumference. In solving problems involving the circle, we must be familiar with several theorems. In order to understand these theorems, we review the names given to parts of a circle. Diameter and chord The region that is encompassed between an arc and a chord is called a segment. The region between the chord and the minor arc is called the minor segment. The region between the chord and the major arc is called the major segment. If the chord is a diameter, then both segments are equal and are called semi-circles. The straight line joining any two points on the circle is called a chord. Sectors A diameter is a chord that passes through the center of the circle. It is, therefore, the longest possible chord of a circle. In the diagram, O is the center of the circle, AB is a diameter and PQ is also a chord. Arcs The region that is enclosed by any two radii and an arc is called a sector. If the region is bounded by the two radii and a minor arc, then it is called the minor sector. www.faspassmaths.comIf the region is bounded by two radii and the major arc, it is called the major sector. An arc of a circle is the part of the circumference of the circle that is cut off by a chord. -

Geometry Course Outline

GEOMETRY COURSE OUTLINE Content Area Formative Assessment # of Lessons Days G0 INTRO AND CONSTRUCTION 12 G-CO Congruence 12, 13 G1 BASIC DEFINITIONS AND RIGID MOTION Representing and 20 G-CO Congruence 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Combining Transformations Analyzing Congruency Proofs G2 GEOMETRIC RELATIONSHIPS AND PROPERTIES Evaluating Statements 15 G-CO Congruence 9, 10, 11 About Length and Area G-C Circles 3 Inscribing and Circumscribing Right Triangles G3 SIMILARITY Geometry Problems: 20 G-SRT Similarity, Right Triangles, and Trigonometry 1, 2, 3, Circles and Triangles 4, 5 Proofs of the Pythagorean Theorem M1 GEOMETRIC MODELING 1 Solving Geometry 7 G-MG Modeling with Geometry 1, 2, 3 Problems: Floodlights G4 COORDINATE GEOMETRY Finding Equations of 15 G-GPE Expressing Geometric Properties with Equations 4, 5, Parallel and 6, 7 Perpendicular Lines G5 CIRCLES AND CONICS Equations of Circles 1 15 G-C Circles 1, 2, 5 Equations of Circles 2 G-GPE Expressing Geometric Properties with Equations 1, 2 Sectors of Circles G6 GEOMETRIC MEASUREMENTS AND DIMENSIONS Evaluating Statements 15 G-GMD 1, 3, 4 About Enlargements (2D & 3D) 2D Representations of 3D Objects G7 TRIONOMETRIC RATIOS Calculating Volumes of 15 G-SRT Similarity, Right Triangles, and Trigonometry 6, 7, 8 Compound Objects M2 GEOMETRIC MODELING 2 Modeling: Rolling Cups 10 G-MG Modeling with Geometry 1, 2, 3 TOTAL: 144 HIGH SCHOOL OVERVIEW Algebra 1 Geometry Algebra 2 A0 Introduction G0 Introduction and A0 Introduction Construction A1 Modeling With Functions G1 Basic Definitions and Rigid -

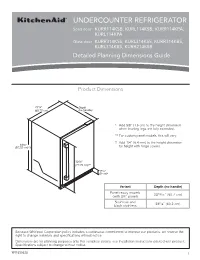

Dimension Guide

UNDERCOUNTER REFRIGERATOR Solid door KURR114KSB, KURL114KSB, KURR114KPA, KURL114KPA Glass door KURR314KSS, KURL314KSS, KURR314KBS, KURL314KBS, KURR214KSB Detailed Planning Dimensions Guide Product Dimensions 237/8” Depth (60.72 cm) (no handle) * Add 5/8” (1.6 cm) to the height dimension when leveling legs are fully extended. ** For custom panel models, this will vary. † Add 1/4” (6.4 mm) to the height dimension 343/8” (87.32 cm)*† for height with hinge covers. 305/8” (77.75 cm)** 39/16” (9 cm)* Variant Depth (no handle) Panel ready models 2313/16” (60.7 cm) (with 3/4” panel) Stainless and 235/8” (60.2 cm) black stainless Because Whirlpool Corporation policy includes a continuous commitment to improve our products, we reserve the right to change materials and specifications without notice. Dimensions are for planning purposes only. For complete details, see Installation Instructions packed with product. Specifications subject to change without notice. W11530525 1 Panel ready models Stainless and black Dimension Description (with 3/4” panel) stainless models A Width of door 233/4” (60.3 cm) 233/4” (60.3 cm) B Width of the grille 2313/16” (60.5 cm) 2313/16” (60.5 cm) C Height to top of handle ** 311/8” (78.85 cm) Width from side of refrigerator to 1 D handle – door open 90° ** 2 /3” (5.95 cm) E Depth without door 2111/16” (55.1 cm) 2111/16” (55.1 cm) F Depth with door 2313/16” (60.7 cm) 235/8” (60.2 cm) 7 G Depth with handle ** 26 /16” (67.15 cm) H Depth with door open 90° 4715/16” (121.8 cm) 4715/16” (121.8 cm) **For custom panel models, this will vary. -

Symmetry of Graphs. Circles

Symmetry of graphs. Circles Symmetry of graphs. Circles 1 / 10 Today we will be interested in reflection across the x-axis, reflection across the y-axis and reflection across the origin. Reflection across y reflection across x reflection across (0; 0) Sends (x,y) to (-x,y) Sends (x,y) to (x,-y) Sends (x,y) to (-x,-y) Examples with Symmetry What is Symmetry? Take some geometrical object. It is called symmetric if some geometric move preserves it Symmetry of graphs. Circles 2 / 10 Reflection across y reflection across x reflection across (0; 0) Sends (x,y) to (-x,y) Sends (x,y) to (x,-y) Sends (x,y) to (-x,-y) Examples with Symmetry What is Symmetry? Take some geometrical object. It is called symmetric if some geometric move preserves it Today we will be interested in reflection across the x-axis, reflection across the y-axis and reflection across the origin. Symmetry of graphs. Circles 2 / 10 Sends (x,y) to (-x,y) Sends (x,y) to (x,-y) Sends (x,y) to (-x,-y) Examples with Symmetry What is Symmetry? Take some geometrical object. It is called symmetric if some geometric move preserves it Today we will be interested in reflection across the x-axis, reflection across the y-axis and reflection across the origin. Reflection across y reflection across x reflection across (0; 0) Symmetry of graphs. Circles 2 / 10 Sends (x,y) to (-x,y) Sends (x,y) to (x,-y) Sends (x,y) to (-x,-y) Examples with Symmetry What is Symmetry? Take some geometrical object. -

Spectral Dimensions and Dimension Spectra of Quantum Spacetimes

PHYSICAL REVIEW D 102, 086003 (2020) Spectral dimensions and dimension spectra of quantum spacetimes † Michał Eckstein 1,2,* and Tomasz Trześniewski 3,2, 1Institute of Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics, National Quantum Information Centre, Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Informatics, University of Gdańsk, ulica Wita Stwosza 57, 80-308 Gdańsk, Poland 2Copernicus Center for Interdisciplinary Studies, ulica Szczepańska 1/5, 31-011 Kraków, Poland 3Institute of Theoretical Physics, Jagiellonian University, ulica S. Łojasiewicza 11, 30-348 Kraków, Poland (Received 11 June 2020; accepted 3 September 2020; published 5 October 2020) Different approaches to quantum gravity generally predict that the dimension of spacetime at the fundamental level is not 4. The principal tool to measure how the dimension changes between the IR and UV scales of the theory is the spectral dimension. On the other hand, the noncommutative-geometric perspective suggests that quantum spacetimes ought to be characterized by a discrete complex set—the dimension spectrum. We show that these two notions complement each other and the dimension spectrum is very useful in unraveling the UV behavior of the spectral dimension. We perform an extended analysis highlighting the trouble spots and illustrate the general results with two concrete examples: the quantum sphere and the κ-Minkowski spacetime, for a few different Laplacians. In particular, we find that the spectral dimensions of the former exhibit log-periodic oscillations, the amplitude of which decays rapidly as the deformation parameter tends to the classical value. In contrast, no such oscillations occur for either of the three considered Laplacians on the κ-Minkowski spacetime. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.102.086003 I. -

Zero-Dimensional Symmetry

Snapshots of modern mathematics № 3/2015 from Oberwolfach Zero-dimensional symmetry George Willis This snapshot is about zero-dimensional symmetry. Thanks to recent discoveries we now understand such symmetry better than previously imagined possible. While still far from complete, a picture of zero-dimen- sional symmetry is beginning to emerge. 1 An introduction to symmetry: spinning globes and infinite wallpapers Let’s begin with an example. Think of a sphere, for example a globe’s surface. Every point on it is specified by two parameters, longitude and latitude. This makes the sphere a two-dimensional surface. You can rotate the globe along an axis through the center; the object you obtain after the rotation still looks like the original globe (although now maybe New York is where the Mount Everest used to be), meaning that the sphere has rotational symmetry. Each rotation is prescribed by the latitude and longitude where the axis cuts the southern hemisphere, and by an angle through which it rotates the sphere. 1 These three parameters specify all rotations of the sphere, which thus has three-dimensional rotational symmetry. In general, a symmetry may be viewed as being a transformation (such as a rotation) that leaves an object looking unchanged. When one transformation is followed by a second, the result is a third transformation that is called the product of the other two. The collection of symmetries and their product 1 Note that we include the rotation through the angle 0, that is, the case where the globe actually does not rotate at all. 1 operation forms an algebraic structure called a group 2 . -

Chapter 14 Hyperbolic Geometry Math 4520, Fall 2017

Chapter 14 Hyperbolic geometry Math 4520, Fall 2017 So far we have talked mostly about the incidence structure of points, lines and circles. But geometry is concerned about the metric, the way things are measured. We also mentioned in the beginning of the course about Euclid's Fifth Postulate. Can it be proven from the the other Euclidean axioms? This brings up the subject of hyperbolic geometry. In the hyperbolic plane the parallel postulate is false. If a proof in Euclidean geometry could be found that proved the parallel postulate from the others, then the same proof could be applied to the hyperbolic plane to show that the parallel postulate is true, a contradiction. The existence of the hyperbolic plane shows that the Fifth Postulate cannot be proven from the others. Assuming that Mathematics itself (or at least Euclidean geometry) is consistent, then there is no proof of the parallel postulate in Euclidean geometry. Our purpose in this chapter is to show that THE HYPERBOLIC PLANE EXISTS. 14.1 A quick history with commentary In the first half of the nineteenth century people began to realize that that a geometry with the Fifth postulate denied might exist. N. I. Lobachevski and J. Bolyai essentially devoted their lives to the study of hyperbolic geometry. They wrote books about hyperbolic geometry, and showed that there there were many strange properties that held. If you assumed that one of these strange properties did not hold in the geometry, then the Fifth postulate could be proved from the others. But this just amounted to replacing one axiom with another equivalent one. -

A Guide to Circle Geometry

A Guide to Circle Geometry Teaching Approach In Paper 2, Euclidean Geometry should comprise 35 marks of a total of 150 in Grade 11 and 40 out of 150 in Grade 12. This section of Mathematics requires both rote learning as well as continuous practice. Pen and paper repetition is the best way to get this right. Each pupil should have a correct handwritten copy of every theorem to refer to and to memorise. The theorems and their proofs, as well as the statement of the converses, must be learned for examination purposes. The theorems, converses, and other axioms must be used to solve riders and should also be used in formal proofs. In these cases the correct (and understandable) abbreviation of a theorem or its corollary can be used. The emphasis during assessment will be on the correctness of formal arguments in examinations and notation will be scrutinised carefully. In most cases the student needs to follow the statement, reason, conclusion format. Please refer to the task answers to ensure correct setting out is followed. The numbering of theorems is author dependent and the reasons ‘Theorem 3’ will not be acceptable; neither will reasons like ‘bow tie’ or ‘wind surfer’. All the results and definitions from previous grades are acceptable as axioms and do not need to be proved for the circle geometry results. The proofs of the theorems should be introduced only after a number of numerical and literal riders have been completed and the learners are comfortable with the application of the theory. When attempting a rider, it is a good idea to use colour to denote angles which are equal as well as cyclic quads, tangents etc.