Art’ of Copyright: a Practitioner’S Perspective, 42 Colum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

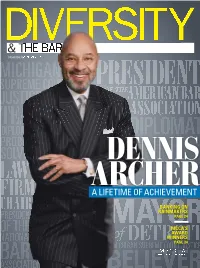

A Lifetime of Achievement

® November/ December 2012 COURT DENNIS ARCHER A LIFETIME OF ACHIEVEMENT DIV E RSITY EXCELLENCE | EDUCATION | EQUITY 0880 MCCA NovDec.indb 1 11/6/12 1:28 PM 11062012133530 DIVERSITY – A KEY INGREDIENT Hunton & Williams LLP congratulates firm partner Fernando Alonso for his selection as a 2 012 Diversity & the Bar Law Firm Rainmaker. At Perkins Coie, diversity is an essential ingredient that helps us create the best solutions for our clients. We value and encourage diverse viewpoints and draw upon them to resolve our clients’ business and legal challenges. Diversity adds perspective and creativity to what we do. It is a key ingredient to our success. “At Hunton & Williams, diversity is one of our greatest assets.” —Wally Martinez, Managing Partner ANCHORAGE · BEIJING · BELLEVUE · BOISE · CHICAGO · DALLAS · DENVER · LOS ANGELES · MADISON · NEW YORK PALO A L T O · PHOENIX · PORTLAND · S A N D I E G O · S A N F R A N C I S C O · S E A T T L E · SHANGHAI · T A I P E I · W A S H I N G T O N , D . C . Contact: 800.586.8441 Perkins Coie LLP ATTORNEY ADVERTISING www.perkinscoie.com Hunton & Williams, 1111 Brickell Avenue, Suite 2500, Miami, FL 33131, 305.810.2500 © 2012 Hunton & Williams LLP www.hunton.com Atlanta Austin Bangkok Beijing Brussels Charlotte Dallas Houston London Los Angeles McLean Miami New York Norfolk Raleigh Richmond San Francisco Tokyo Washington 0880 MCCA NovDec.indb 2 11/6/12 1:28 PM 11062012133530 Hunton & Williams LLP congratulates firm partner Fernando Alonso for his selection as a 2 012 Diversity & the Bar Law Firm Rainmaker. -

In Silicon Valley

in Silicon Valley weil.com/careers Welcome to Silicon Valley At Weil’s Silicon Valley office, you’ll find a truly unique place to launch your legal career. We are committed to providing associates with exciting, challenging, and fulfilling learning experiences, starting on day one. We offer a collegial working environment in which teamwork and supporting one another is valued and practiced every day. As an integral part of our team, you’ll quickly dive into some of the most complex, high-profile transactions and litigation that can be found anywhere in the world. Under the guidance and mentoring of partners and senior associates, your professional development will accelerate, and you will soon find yourself with skills, experience, and expertise that far exceed your peers at other firms. We established our Silicon Valley office in 1991 and have over time built one of the most impressive law firm practices in the Bay Area. Our lawyers are consistently ranked at the top of their practice areas, and our client list is arguably the best of any firm in California. Weil’s Silicon Valley office is an important part of a truly global powerhouse law firm with a distinguished history. With offices in twenty of the most important commercial markets around the world, we are able to effectively serve our Silicon Valley clients with respect to their legal needs, wherever those needs may arise. We sincerely hope that you will consider becoming part of our team in Silicon Valley as you embark upon your legal career. Craig W. Adas, Silicon Valley Office Managing Partner With 1,100 lawyers in offices on three continents around the world, Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP offers an unparalleled global platform for developing your legal practice. -

Weil Diversity Bifold

INCLUSION IS IN OUR weil.com/about-weil/diversity-equity-and-inclusion Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) have been our core values since Frank Weil, Sylvan Gotshal, and Horace Manges found many doors closed to them because of their religious beliefs. They founded Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP to open those doors. For over 30 years, Weil has been an outspoken leader in empowering and engendering an inclusive culture. Client Diversity Events All of Weil’s affinity groups work to enhance their individual members' networks and client development skills while contributing to the Firm’s bottom line. The affinity 5Affinity Groups: groups collaborate to host client events such as film screening events for Black Panther, Crazy Rich Asians, Harriet and RBG. Pan-affinity group lunch and dinner programs provide AsianAttorneys@Weil opportunities to connect and learn from clients and alumni, such as a Black Attorney Black Attorney Affinity Group Affinity Group, and WeilPride dinner with SoundCloud General Counsel, Antonious Porch. WeilLatinx Affinity Group WeilPride (LGBTQ+) Conferences Women@Weil Weil has been a leader among law firms for holding firmwide conferences for Asian, Black, Latinx, and LGBTQ+ Racial Justice & Equity attorneys. The conferences Asian Attorneys at Weil Conference 2019 In 2020, the Firm recommitted to our racial justice bring together summer efforts internally and externally. This commitment associates and attorneys from included the launch of the Racial Justice speaker across the Firm’s offices for series, with 20+ programs held to date, joining the Law professional development, Firm Antiracism Alliance internal networking and (LFAA), signing statements mentoring, and client condemning anti-Semitism development efforts. -

View the Silicon Valley Office's Corporate Social Responsibility

Silicon Valley Office’s Corporate Social Responsibility Review 1991-2016 Contents 04 Timeline 05 Introduction 06 Pro Bono 16 Feature Story: Ending Indeterminate Long-Term Solitary Confinement in California 20 Weil Gives Back 24 ‘There’s a Lot of Heart in This Office’: How CSR Became Part of the Culture 26 Diversity & Inclusion 32 Alumni Feature: Chipping Away at Tech’s Glass Ceiling 34 Sustainability Silicon Valley office opens 1991 1992 Represents 1993 San Francisco AIDS Foundation 1994 1995 Moves from Sand Hill Road to Redwood Shores Parkway 1996 1997 Represents 1998 The Tech Museum of Innovation 1999 2000 2001 Begins partnership with 2002 Make-a-Wish Foundation Weil Silicon Valley team 2003 participates in its first San Francisco AIDS Walk 2004 2005 Kicks off the annual 2006 Family Giving Tree toy drive 2007 Officially launches the Silicon Valley office 2008 Begins partnership Green Committee with a local high 2009 school to host annual Job Shadow Day 2010 2011 Participates in the JP Morgan Landmark settlement Corporate Challenge® 2012 that ends indeterminate 2013 long-term solitary confinement in 2014 California prisons 2015 Weil Silicon Valley Office renovation completed celebrates 2016 25th anniversary Weil Silicon Valley Timeline Introduction | Weil’s Silicon Valley office celebrated its 25th anniversary on November 5, 2016. Since 1991, we have built one of the most impressive law firm practices on the West Coast. Our lawyers are consistently ranked at the top of their practice areas, and we represent many of the world’s most successful and innovative companies and private equity funds. An integral part of the office’s culture is our dedication to the community. -

Diversity Fellowship for 1L Law School Students

Diversity Fellowship For 1L Law School Students One of the qualities distinguishing Weil from our Application peers is our culture. Diversity, equity and inclusion To be considered for the Weil 1L Diversity Fellowship (DEI) have been core values since our founding. Program, please submit an online application. Frank Weil, Sylvan Gotshal, and Horace Manges Your completed online application package must established the Firm to open doors that were include the following items: previously closed to them because of their religious ■ Resumé beliefs. For decades, Weil has been an outspoken leader in empowering and engendering an inclusive ■ Unofficial or Official Law School Transcript culture. Today, the diversity of our attorneys, ■ Personal Statement (no more than two (2) pages, paralegals and staff is one of our greatest strengths. double spaced) We created the Weil 1L Diversity Fellowship Please include the grades you have at the time of submission. You may update your online application by Program to welcome the next generation of diverse following the link you will receive in a confirmation email attorneys who want to pursue careers at Weil. upon submission. To become a Weil 1L Diversity Fellow, you must be enrolled in an It is not necessary to apply to the summer associate ABA-accredited law school and intend to practice law in a major program separately; your completed application denotes city of the United States. You must have successfully completed consideration for the entire summer program/scholarship the first semester of your first year of a full-time JD program, package. In your personal statement, we request that you with an expected graduation date of spring 2023, and you may discuss how you will contribute to diversity in the legal not be the recipient of a similar scholarship award from another profession generally, including (to the extent applicable) law firm. -

Diversity Fellowship for 2L Law School Students

Diversity Fellowship For 2L Law School Students One of the qualities distinguishing Weil from our The Weil 2L Diversity Scholars Program application peers is our culture. Diversity, equity and inclusion will be available to apply online at careers.weil.com for (DEI) have been core values since our founding. students interested in applying for the 2L Fellowship on November 1, 2020. The application process is open to Frank Weil, Sylvan Gotshal, and Horace Manges all law school students who fulfill the fellowship’s established the Firm to open doors that were eligibility requirements. previously closed to them because of their religious beliefs. For decades, Weil has been an outspoken Application leader in empowering and engendering an inclusive To be considered for the Weil 2L Diversity Fellowship culture. Today, the diversity of our attorneys, Program, please submit an online application. paralegals and staff is one of our greatest strengths. Your completed online application package must We created the Weil 2L Diversity Fellowship include the following items: Program to welcome the next generation of diverse attorneys who want to pursue careers at Weil. ■ Resumé ■ Unofficial or Official Law School Transcript The Weil 2L Diversity Fellowship is available to students who ■ Personal Statement (no more than two (2) pages, are enrolled in an ABA-accredited law school and intend to double spaced) practice law in a major city of the United States in which Weil Please include the grades you have at the time of has an office. Eligible students must have successfully submission; you may update your online application by completed their first year of a full-time JD program, with an following the link you will receive in a confirmation email expected graduation date of spring 2022, and may not be the upon submission. -

Black Student's Guide to Law Schools & Firms

Why Howard Is #1 Paul Weiss Has Largest Percentage of Black Attorneys Is Full Employment Possible? When Being the “Only One” Is Worth It Large Law Firm Black Attorney Percentages Over 40 Boutiques with No Black Attorneys Black Student’s Guide to Law Schools & Firms 2019 Edition 1 Diversity + Inclusion Strategic Plan We are proud that Foley is one of the first law firms in the country to adopt a Diversity + Inclusion Strategic Plan. The goal of our three-year strategy is simple: to provide the best service to our clients by attracting, retaining, developing and promoting the best talent. Key Action Steps Strategic Objectives ■ Design inclusion training for firm leadership ■ Require attorney and sta participation in such trainings ■ Enhance individual evaluations to assess support of the plan Establish a culture ■ of accountability that Meet regularly and review progress on implementation of the key actions promotes diversity and ■ Provide a progress report to firm leadership inclusion ■ Establish an oversight program to ensure new associates have sufficient Ensure all individuals amount of the right type of work receive meaningful and ■ Revise mentoring program to include a dashboard report of key data challenging assignments ■ Develop core competencies focusing on necessary skills and experience and opportunities that help ■ Implement succession planning and growth of client interaction milestones them develop professionally ■ Provide for inclusion of diverse attorneys in pitch and proposal activity ■ Expand the current sta talent management -

Inclusion Is in Our

Inclusion is in our careers.weil.comDNA A commitment to diversity and inclusion has been at the core of our firm since Frank Weil, Sylvan Gotshal, and Horace Manges found many doors closed to them because of their religious beliefs. They founded Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP to open those doors. For over 30 years, Weil has been a leader in investing in formal initiatives to cultivate an inclusive culture where all feel comfortable and encouraged to excel. 5 Affinity Groups: Individual Affinity Group Conferences AsianAttorneys@Weil Black Attorney Affinity Group Latinos@Weil WEGALA (LGBT Affinity Group) Women@Weil In 2015, Weil launched Upstanders@Weil to establish an explicit role for diversity allies and promote greater inclusion for all groups. Weil is unique among law firms for holding individual firmwide conferences for Asian, Upstanders are allies, supporters and advocates for Black, Latino, and LGBT attorneys. The conferences bring together summer associates and attorneys from across the Firm’s offices for professional development, internal people and communities that share a different networking and mentoring, client development, and pipeline development efforts. background or identity than one’s own. To date, the Firm has held 11 individual affinity group conferences. Above, members ▪ Launched with a cross-office panel and video of the Firm's WEGALA (LGBT Affinity Group) and summer associates from the US and London offices convened in 2016. In January 2017, the Firm is holding a global ▪ Upstander Action Guide and an intranet site Multicultural Attorney conference. □ 50+ upstander behaviors □ 40+ resources ▪ Interactive diversity theater program utilized professional actors and guided group discussions Client Diversity Events □ 20 sessions across 8 offices ▪ Andrea Bernstein Upstander@Weil Awards □ 70+ honorees to date TOWER is a committee of female and male partners from across the Firm focused on the advancement and development of female attorneys globally. -

Diversity Fellowship for 2L Law School Students

Diversity Fellowship For 2L Law School Students Inclusion is in our DNA. A commitment to Application diversity and inclusion has been at the core of To be considered for the Weil 2L Diversity Fellowship our Firm since Frank Weil, Sylvan Gotshal, and Program, please click here to complete and submit an Horace Manges found many doors closed to online application. them because of their religious beliefs. They Your completed online application package must founded Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP to open include the following items: those doors. Our attorneys, paralegals and ■■ Resumé staff throughout the world are composed of a ■■ Unofficial or Official Law School Transcript rich mixture of men and women of different ■■ Personal Statement (no more than two (2) pages, races, ethnic backgrounds, cultures and double spaced) primary languages. We are strengthened Please note, while we do require a law school transcript, enormously by this diversity. The Weil 2L we understand that some schools will not release first year grades by the application deadline. Please include the Diversity Fellowship Program is designed to grades you have at the time of submission; you may update increase the number of diverse attorneys who your online application by following the link you will receive want to pursue careers at Weil. in a confirmation email upon submission. It is not necessary to apply to the summer associate The Weil 2L Diversity Fellowship is available to students program separately; this completed application denotes who are enrolled in an ABA-accredited law school and consideration for the entire summer program/scholarship intend to practice law in a major city of the United States in package. -

Diversity Fellowship for 2L Law School Students

Diversity Fellowship For 2L Law School Students One of the qualities distinguishing Weil from our The Weil 2L Diversity Scholars Program application peers is our culture. Diversity, equity and inclusion will be available to apply online at careers.weil.com for (DEI) have been core values since our founding. students interested in applying for the 2L Fellowship on November 1, 2020. The application process is open to Frank Weil, Sylvan Gotshal, and Horace Manges all law school students who fulfill the fellowship’s established the Firm to open doors that were eligibility requirements. previously closed to them because of their religious beliefs. For decades, Weil has been an outspoken Application leader in empowering and engendering an inclusive To be considered for the Weil 2L Diversity Fellowship culture. Today, the diversity of our attorneys, Program, please submit an online application. paralegals and staff is one of our greatest strengths. Your completed online application package must We created the Weil 2L Diversity Fellowship include the following items: Program to welcome the next generation of diverse attorneys who want to pursue careers at Weil. ■ Resumé ■ Unofficial or Official Law School Transcript The Weil 2L Diversity Fellowship is available to students who ■ Personal Statement (no more than two (2) pages, are enrolled in an ABA-accredited law school and intend to double spaced) practice law in a major city of the United States in which Weil Please include the grades you have at the time of has an office. Eligible students must have successfully submission; you may update your online application by completed their first year of a full-time JD program, with an following the link you will receive in a confirmation email expected graduation date of spring 2022, and may not be the upon submission. -

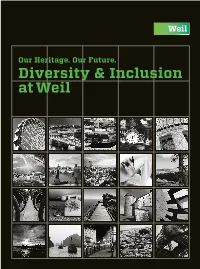

Diversity & Inclusion at Weil

Our Heritage. Our Future. Diversity & Inclusion at Weil Weil’s Diversity Brochure captures our firm’s commitment to inclusion One of the qualities that separates Weil from As Chair of Weil’s Diversity Committee, I am in more ways than one. All of the photography used to illustrate this our peers is our culture. We strive to create honored to help build on our heritage to foster brochure was created by Weil employees and selected from more than an environment in which all of our people feel a culture of inclusion and respect. 300 submissions from across the firm. These visual narratives illustrate comfortable and supported to be able to achieve I know from personal experience how the firm’s their potential. This creates a “home team the incredible diversity of perspectives, subjects, and styles of our commitment to diversity and inclusion — and its advantage” of colleagues working together and attorneys and staff — and we think there is no better way to capture our encouraging each other to excel. openness to new ideas — creates pathways for vision of diversity and inclusion than to showcase their creativity. This success. I began my career at Weil as a full-time collection is a visual expression of Weil’s heritage of diversity and This inclusive culture enables us to consistently associate and left after three years. I was welcomed current vision for inclusion. Credits for each featured artist can be deliver superior service and results to our clients. back five years later (having spent most of my found on page 12. We call it the “wow factor.” We achieve it by time away as the full-time mother of a young son) working together as a team to develop innovative and was given an opportunity, unique at the time, approaches and solutions. -

Mission Purpose &

Connecting Weil’s People with Mission & Purpose The Firm’s corporate citizenship footprint is brought to bear through Weil’s industry leading diversity & inclusion, pro bono legal service, sustainability, community engagement, and charitable contributions programs. Whether it be leveraging the subject matter expertise of our attorneys and administrative staff, providing volunteer hands-on support or financial resources to our network of nonprofit partners, Weil is committed to engaging as a responsible corporate citizen in the communities where we live and work. Diversity & Inclusion Workplace Diversity & Inclusion Efforts A commitment to diversity and inclusion has been at the core of our Firm since Frank Weil, Sylvan Gotshal, and Horace Manges found many doors closed to them because of their Upstander@Weil religious beliefs. They founded Weil, Upstander@Weil seeks to inspire each and every Weil employee Gotshal & Manges LLP to open those to stand up for inclusion in the workplace and at home. Upstanders doors. For over 30 years, Weil has are allies, supporters, and advocates for people and communities been a leader in investing in formal that share a different background or identity than their own. initiatives to cultivate an inclusive The Upstander program, launched in 2015, features an award culture where all feel comfortable for staff and attorneys who exhibit inclusive and ally behaviors, and encouraged to excel. Weil’s as well as an extensive training and education program. award winning diversity program includes five active affinity groups, recruiting and pipeline initiatives, and 70+ Upstander Award education and leadership programs. recipients since 2015 Community-Based Pipeline Initiatives Weil is proud of its continued efforts engaging with students from the Big Brothers Big Sisters of NYC, PALS and PENCIL programs, exposing adolescents and young adults to future professional opportunities and careers in the legal profession.