Observing Moon and Planets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

10Great Features for Moon Watchers

Sinus Aestuum is a lava pond hemming the Imbrium debris. Mare Orientale is another of the Moon’s large impact basins, Beginning observing On its eastern edge, dark volcanic material erupted explosively and possibly the youngest. Lunar scientists think it formed 170 along a rille. Although this region at first appears featureless, million years after Mare Imbrium. And although “Mare Orien- observe it at several different lunar phases and you’ll see the tale” translates to “Eastern Sea,” in 1961, the International dark area grow more apparent as the Sun climbs higher. Astronomical Union changed the way astronomers denote great features for Occupying a region below and a bit left of the Moon’s dead lunar directions. The result is that Mare Orientale now sits on center, Mare Nubium lies far from many lunar showpiece sites. the Moon’s western limb. From Earth we never see most of it. Look for it as the dark region above magnificent Tycho Crater. When you observe the Cauchy Domes, you’ll be looking at Yet this small region, where lava plains meet highlands, con- shield volcanoes that erupted from lunar vents. The lava cooled Moon watchers tains a variety of interesting geologic features — impact craters, slowly, so it had a chance to spread and form gentle slopes. 10Our natural satellite offers plenty of targets you can spot through any size telescope. lava-flooded plains, tectonic faulting, and debris from distant In a geologic sense, our Moon is now quiet. The only events by Michael E. Bakich impacts — that are great for telescopic exploring. -

Lunar Club Observations

Guys & Gals, Here, belatedly, is my Christmas present to you. I couldn’t buy each of you a lunar map, so I did the next best thing. Below this letter you’ll find a guide for observing each of the 100 lunar features on the A. L.’s Lunar Club observing list. My guide tells you what the features are, where they are located, what instrument (naked eyes, binoculars or telescope) will give you the best view of them and what you can expect to see when you find them. It may or may not look like it, but this project involved a massive amount of work. In preparing it, I relied heavily on three resources: *The lunar map I used to determine which quadrant of the Moon each feature resides in is the laminated Sky & Telescope Lunar Map – specifically, the one that shows the Moon as we see it naked-eye or in binoculars. (S&T also sells one with the features reversed to match the view in a refracting telescope for the same price.); and *The text consists of information from (a) my own observing notes and (b) material in Ernest Cherrington’s Exploring the Moon Through Binoculars and Small Telescopes. Both the map and Cherrington’s book were door prizes at our Dec. Christmas party. My goal, of course, is to get you interested in learning more about our nearest neighbor in space. The Moon is a fascinating and lovely place, and one that all too often is overlooked by amateur astronomers. But of all the objects in the night sky, the Moon is the most accessible and easiest to observe. -

January 2018

The StarGazer http://www.raclub.org/ Newsletter of the Rappahannock Astronomy Club No. 3, Vol. 6 November 2017–January 2018 Field Trip to Randolph-Macon College Keeble Observatory By Jerry Hubbell and Linda Billard On December 2, Matt Scott, Jean Benson, Bart and Linda Billard, Jerry Hubbell, and Peter Orlowski joined Scott Lansdale to tour the new Keeble Observatory at his alma mater, Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, VA. The Observatory is a cornerstone instrument in the College's academic minor program in astrophysics and is also used for student and faculty research projects. At the kind invitation of Physics Professor George Spagna— Scott’s advisor during his college days and now the director of the new facility—we received a private group tour. We stayed until after dark to see some of its capabilities. Keeble Observatory at Randolph-Macon College Credit: Jerry Hubbell The observatory, constructed in summer 2017, is connected to the northeast corner of the Copley Science Center on campus. It houses a state-of-the-art $30,000 Astro Systeme Austria (ASA) Ritchey-Chretien telescope with a 16-inch (40-cm) primary mirror. Instrumentation will eventually include CCD cameras for astrophotography and scientific imaging, and automation for the 12-foot (3.6-m) dome. The mount is a $50,000 ASA DDM 160 Direct Drive system placed on an interesting offset pier system that allows the mount to track well past the meridian without having to do the pier-flip that standard German equatorial mounts (GEMs) perform when approaching the meridian. All told, the fully outfitted observatory will be equipped with about $100,000 of instrumentation and equipment. -

Thumbnail Index

Thumbnail Index The following five pages depict each plate in the book and provide the following information about it: • Longitude and latitude of the main feature shown. • Sun’s angle (SE), ranging from 1°, with grazing illumination and long shadows, up to 72° for nearly full Moon conditions with the Sun almost overhead. • The elevation or height (H) in kilometers of the spacecraft above the surface when the image was acquired, from 21 to 116 km. • The time of acquisition in this sequence: year, month, day, hour, and minute in Universal Time. 1. Gauss 2. Cleomedes 3. Yerkes 4. Proclus 5. Mare Marginis 79°E, 36°N SE=30° H=65km 2009.05.29. 05:15 56°E, 24°N SE=28° H=100km 2008.12.03. 09:02 52°E, 15°N SE=34° H=72km 2009.05.31. 06:07 48°E, 17°N SE=59° H=45km 2009.05.04. 06:40 87°E, 14°N SE=7° H=60km 2009.01.10. 22:29 6. Mare Smythii 7. Taruntius 8. Mare Fecunditatis 9. Langrenus 10. Petavius 86°E, 3°S SE=19° H=58km 2009.01.11. 00:28 47°E, 6°N SE=33° H=72km 2009.05.31. 15:27 50°E, 7°S SE=10° H=64km 2009.01.13. 19:40 60°E, 11°S SE=24° H=95km 2008.06.08. 08:10 61°E, 23°S SE=9° H=65km 2009.01.12. 22:42 11.Humboldt 12. Furnerius 13. Stevinus 14. Rheita Valley 15. Kaguya impact point 80°E, 27°S SE=42° H=105km 2008.05.10. -

Guide to Observing the Moon

Your guide to The Moonby Robert Burnham A supplement to 618128 Astronomy magazine 4 days after New Moon south is up to match the view in a the crescent moon telescope, and east lies to the left. f you look into the western sky a few evenings after New Moon, you’ll spot a bright crescent I glowing in the twilight. The Moon is nearly everyone’s first sight with a telescope, and there’s no better time to start watching it than early in the lunar cycle, which begins every month when the Moon passes between the Sun and Earth. Langrenus Each evening thereafter, as the Moon makes its orbit around Earth, the part of it that’s lit by the Sun grows larger. If you look closely at the crescent Mare Fecunditatis zona I Moon, you can see the unlit part of it glows with a r a ghostly, soft radiance. This is “the old Moon in the L/U. p New Moon’s arms,” and the light comes from sun- /L tlas Messier Messier A a light reflecting off the land, clouds, and oceans of unar Earth. Just as we experience moonlight, the Moon l experiences earthlight. (Earthlight is much brighter, however.) At this point in the lunar cycle, the illuminated Consolidated portion of the Moon is fairly small. Nonetheless, “COMET TAILS” EXTENDING from Messier and Messier A resulted from a two lunar “seas” are visible: Mare Crisium and nearly horizontal impact by a meteorite traveling westward. The big crater Mare Fecunditatis. Both are flat expanses of dark Langrenus (82 miles across) is rich in telescopic features to explore at medium lava whose appearance led early telescopic observ- and high magnification: wall terraces, central peaks, and rays. -

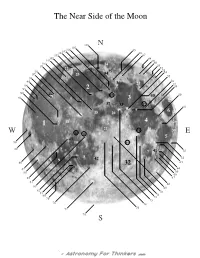

A Map of the Visible Side of the Moon

The Near Side of the Moon 108 N 107 106 105 45 104 46 103 47 102 48 101 49 100 24 50 99 51 52 22 53 98 33 35 54 97 34 23 55 96 95 56 36 25 57 94 58 93 2 92 44 15 40 59 91 3 27 37 17 38 60 39 6 19 20 26 28 1 18 4 29 21 11 30 W 12 E 14 5 43 90 10 16 89 7 41 61 8 62 9 42 88 32 63 87 64 86 31 65 66 85 67 84 68 83 69 82 81 70 80 71 79 72 73 78 74 77 75 76 S Maria (Seas) Craters 1 - Oceanus Procellarum (Ocean of Storms) 45 - Aristotles 77 - Tycho 2 - Mare Imbrium (Sea of Showers) 46 - Cassini 78 - Pitatus 3 - Mare Serenitatis (Sea of Serenity) 47 - Eudoxus 79 - Schickard 4 - Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility) 48 - Endymion 80 - Mercator 5 - Mare Fecunditatis (Sea of Fertility) 49 - Hercules 81 - Campanus 6 - Mare Crisium (Sea of Crises) 50 - Atlas 82 - Bulliadus 7 - Mare Nectaris (Sea of Nectar) 51 - Mercurius 83 - Fra Mauro 8 - Mare Nubium (Sea of Clouds) 52 - Posidonius 84 - Gassendi 9 - Mare Humorum (Sea of Moisture) 53 - Zeno 85 - Euclides 10 - Mare Cognitum (Known Sea) 54 - Menelaus 86 - Byrgius 18 - Mare Insularum (Sea of Islands) 55 - Le Monnier 87 - Billy 19 - Sinus Aestuum (Bay of Seething) 56 - Vitruvius 88 - Cruger 20 - Mare Vaporum (Sea of Vapors) 57 - Cleomedes 89 - Grimaldi 21 - Sinus Medii (Bay of the Center) 58 - Plinius 90 - Riccioli 22 - Sinus Roris (Bay of Dew) 59 - Magelhaens 91 - Galilaei 23 - Sinus Iridum (Bay of Rainbows) 60 - Taruntius 92 - Encke T 24 - Mare Frigoris (Sea of Cold) 61 - Langrenus 93 - Eddington 25 - Lacus Somniorum (Lake of Dreams) 62 - Gutenberg 94 - Seleucus 26 - Palus Somni (Marsh of Sleep) -

AL Lunar 100

AL Lunar 100 The AL Lunar 100 introduces amateur astronomers to that object in the sky that most of us take for granted, and which deep sky observers have come to loathe. But even though deep sky observers search for dark skies (when the moon is down), this list gives them something to do when the moon is up. In other words, it gives us something to observe the rest of the month, and we all know that the sky is always clear when the moon is up. The AL Lunar 100 also allows amateurs in heavily light polluted areas to participate in an observing program of their own. This list is well suited for the young, inexperienced observer as well as the older observer just getting into our hobby since no special observing skills are required. It is well balanced because it develops naked eye, binocular, and telescopic observing skills. The AL Lunar 100 consists of 100 features on the moon. These 100 features are broken down into three groups: 18 naked eye, 46 binocular, and 36 telescopic features. Any pair of binoculars and any telescope may be used for this list. This list does not require expensive equipment. Also, if you have problems with observing the features at one level, you may go up to the next higher level. In other words, if you have trouble with any of the naked eye objects, you may jump up to binoculars. If you have trouble with any of the binocular objects, then you may move up to a telescope. Before moving up to the next higher level, please try to get as many objects as you can with the instrument required at that level. -

Observing the Moon

OBSERVING THE MOON The Moon is all too often dismissed by amateur astronomers as a nuisance, a source of light pollution that spoils an otherwise clear dark night. And in fact there are no celestial objects other than the Sun that can even remotely compete with old Luna when she rides high and bright in the night sky. For people devoted to the observation of deep sky objects the Moon means the end of observing for the night, or hours of waiting for the Moon to set. Or clear nights with no observing at all. Of course, a better way to think about the Moon is to see it as a source of observing opportunities, especially for smaller telescopes. The Moon is an entire world hanging above our heads, an alien planet that can be studied at a level of detail that Mars, Jupiter, or Saturn cannot come close to matching. The Moon is worth the time and effort to observe and study. Or look at it this way. The Moon is not going to go away. So if you can’t beat it, observe it! Observing the Moon is all about learning your way around an alien landscape. When you learn terrestrial geography you learn to recognize features such as mountains, lakes, rivers, and canyons. Our approach to taking a better look at the Moon will parallel this idea, and although some geographical features (mountains) are recognizably similar to their Earthly counterparts, others (such as craters) are like nothing you will see here. And that is because the Moon is airless, with no weather, and consequently no weathering or erosion. -

Morphology and Origin of Lunar Craters Von R

Morphology and origin of lunar craters Von R. S. Saunders, E. L. Haines, and J. E. Conel, Pasaderia" Summary: The general concensus among lunar geologists is th.at the majority of lunar craters, up to a few km in diameter, are of Impact origm. This conclusion is based on morphologie comparison with terrestrial meteorite craters, consideration of lunar regolrth formation by impact, direct observation of the morphology of smalI and microscopic craters on the lunar surface and experimental impact studtcs. Most Iarge craters are also interpreted to be ()f Impact origin. Although the morphology of unmodified craters changes somewhat with increasing size, these changes are completely gradational and there is no evidence to suggest that the predominant process of crater formation is different for large craters. However, selected craters of various sizes have been interpreted as volcanic. Understanding the origm of the multi-ring b asms presents greater difficulties. Theoretical treatments such as those of Bjork (1961) and Van Dorn (1969) seem to be the only approach. In such treatments it is nccessary to iriclude, in addition to hydrodynamic flow, large plastrc deformation arid br.it.tle failure of the target material, processes that are known to accompany Impact phenomena. Thus complete equations of state are required as well as a detailed microscopic (perhaps statistical) description of imperfections in rock mechanical properties. The required physical parameters arid the calculations are clearly formidable. Analysis of tracking data from Orbiter V has revealed positive graviational anomalies (mascons) over the circular maria (Mulle r und Sjogren, 1968). While a number of theories for the origin of the mascons has been proposed (see Kaula, 1969 for a summary), the nature of the anomalous masses remains in doubt as does the mechamsm whereby excess mass has been added to specific rcgtons, Resolution of these questions will tell us much about the thermal and struc tural history of the Moon. -

The Isabel Williamson Lunar Observing Program

The Isabel Williamson Lunar Observing Program by The RASC Observing Committee Revised Third Edition September 2015 © Copyright The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR The Isabel Williamson Lunar Observing Program Foreword by David H. Levy vii Certificate Guidelines 1 Goals 1 Requirements 1 Program Organization 2 Equipment 2 Lunar Maps & Atlases 2 Resources 2 A Lunar Geographical Primer 3 Lunar History 3 Pre-Nectarian Era 3 Nectarian Era 3 Lower Imbrian Era 3 Upper Imbrian Era 3 Eratosthenian Era 3 Copernican Era 3 Inner Structure of the Moon 4 Crust 4 Lithosphere / Upper Mantle 4 Asthenosphere / Lower Mantle 4 Core 4 Lunar Surface Features 4 1. Impact Craters 4 Simple Craters 4 Intermediate Craters 4 Complex Craters 4 Basins 5 Secondary Craters 5 2. Main Crater Features 5 Rays 5 Ejecta Blankets 5 Central Peaks 5 Terraced Walls 5 ii Table of Contents 3. Volcanic Features 5 Domes 5 Rilles 5 Dark Mantling Materials 6 Caldera 6 4. Tectonic Features 6 Wrinkle Ridges 6 Faults or Rifts 6 Arcuate Rilles 6 Erosion & Destruction 6 Lunar Geographical Feature Names 7 Key to a Few Abbreviations Used 8 Libration 8 Observing Tips 8 Acknowledgements 9 Part One – Introducing the Moon 10 A – Lunar Phases and Orbital Motion 10 B – Major Basins (Maria) & Pickering Unaided Eye Scale 10 C – Ray System Extent 11 D – Crescent Moon Less than 24 Hours from New 11 E – Binocular & Unaided Eye Libration 11 Part Two – Main Observing List 12 1 – Mare Crisium – The “Sea of Cries” – 17.0 N, 70-50 E; -

May 2021 the Lunar Observer by the Numbers

A Publication of the Lunar Section of ALPO Edited by David Teske: [email protected] 2162 Enon Road, Louisville, Mississippi, USA Back issues: http://www.alpo-astronomy.org/ Online readers, May 2021 click on images In This Issue for hyperlinks Observations Received 2 By the Numbers 4 Stöfler and Maurolycus Region, H. Eskildsen 5 North-ish, R. Hill 6 Medii to Delaunay and a Concentric Crater, H. Eskildsen 7 The Greatest Crater? R. Hill 8 The Glorious Rupes Cauchy, A. Anunziato 9 The Western Chain on the Eastern Moon, H. Eskildsen 10 A Scarp by any Other Name, R. Hill 11 Mädlers Bright Streak, Ray or Elevation? A. Anunziato 12 Caucasus to Mare Vaporum, Close-Up Images of Aristillus, Autolycus and Putredinis Domes, H. Eskildsen 15 Images of Crater Schickard, J. D. Sabia 17 Another Trio, R. Hill 18 Mare Vaporum to Sinus Medii and Associated Domes, H. Eskildsen 19 Focus-On: The Lunar 100 Features 61-70, J. Hubbell 21 Lunar 61-70, A. Anunziato 24 Mösting A, R. H. Hays, Jr. 26 Hortensius and Domes, R. H. Hays, Jr. 53 Mare Humboldtianum, the Other Multi-Ring Lunar Basin, D. Teske 75 Recent Lunar Topographic Studies 81 Lunar Geologic Change Detection Program, T. Cook 100 ALPO 2021 Conference News 108 Lunar Calendar May 2021 110 An Invitation to Join ALPO 110 Submission Through the ALPO Image Achieve 111 When Submitting Observations to the ALPO Lunar Section 112 Call For Observations Focus-On 112 Focus-On Announcement 113 Key to Images in this Issue 114 The May issue of The Lunar Observer features a number of interesting articles by Howard Eskildsen, Rob- ert H.