Número 23 • Octubre 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biolphilately Vol-64 No-3

BIOPHILATELY OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE BIOLOGY UNIT OF ATA MARCH 2020 VOLUME 69, NUMBER 1 Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite 'em, And little fleas have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum. —Augustus De Morgan Dr. Indraneil Das Pangolins on Stamps More Inside >> IN THIS ISSUE NEW ISSUES: ARTICLES & ILLUSTRATIONS: From the Editor’s Desk ......................... 1 Botany – Christopher E. Dahle ............ 17 Pangolins on Stamps of the President’s Message .............................. 2 Fungi – Paul A. Mistretta .................... 28 World – Dr. Indraneil Das ..................7 Secretary -Treasurer’s Corner ................ 3 Mammalia – Michael Prince ................ 31 Squeaky Curtain – Frank Jacobs .......... 15 New Members ....................................... 3 Ornithology – Glenn G. Mertz ............. 35 New Plants in the Philatelic News of Note ......................................... 3 Ichthyology – J. Dale Shively .............. 57 Herbarium – Christopher Dahle ....... 23 Women’s Suffrage – Dawn Hamman .... 4 Entomology – Donald Wright, Jr. ........ 59 Rats! ..................................................... 34 Event Calendar ...................................... 6 Paleontology – Michael Kogan ........... 65 New Birds in the Philatelic Wedding Set ........................................ 16 Aviary – Charles E. Braun ............... 51 Glossary ............................................... 72 Biology Reference Websites ................ 69 ii Biophilately March 2020 Vol. 69 (1) BIOPHILATELY BIOLOGY UNIT -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

N° English Name Scientific Name Status Day 1

1 FUNDACIÓN JOCOTOCO CHECK-LIST OF THE BIRDS OF YANACOCHA N° English Name Scientific Name Status Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 1 Tawny-breasted Tinamou Nothocercus julius R 2 Curve-billed Tinamou Nothoprocta curvirostris U 3 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata 4 Andean Teal Anas andium 5 Andean Guan Penelope montagnii U 6 Sickle-winged Guan Chamaepetes goudotii 7 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 8 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus 9 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 10 Andean Condor Vultur gryphus R Sharp-shinned Hawk (Plain- 11 breasted Hawk) Accipiter striatus U 12 Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus 13 Black-and-chestnut Eagle Spizaetus isidori 14 Cinereous Harrier Circus cinereus 15 Roadside Hawk Rupornis magnirostris 16 White-rumped Hawk Parabuteo leucorrhous 17 Black-chested Buzzard-Eagle Geranoaetus melanoleucus U 18 White-throated Hawk Buteo albigula R 19 Variable Hawk Geranoaetus polyosoma U 20 Andean Lapwing Vanellus resplendens VR 21 Rufous-bellied Seedsnipe Attagis gayi 22 Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda R 23 Baird's Sandpiper Calidris bairdii VR 24 Andean Snipe Gallinago jamesoni FC 25 Imperial Snipe Gallinago imperialis U 26 Noble Snipe Gallinago nobilis 27 Jameson's Snipe Gallinago jamesoni 28 Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius 29 Band-tailed Pigeon Patagoienas fasciata FC 30 Plumbeous Pigeon Patagioenas plumbea 31 Common Ground-Dove Columbina passerina 32 White-tipped Dove Leptotila verreauxi R 33 White-throated Quail-Dove Zentrygon frenata U 34 Eared Dove Zenaida auriculata U 35 Barn Owl Tyto alba 36 White-throated Screech-Owl Megascops -

Ornithological Surveys in Serranía De Los Churumbelos, Southern Colombia

Ornithological surveys in Serranía de los Churumbelos, southern Colombia Paul G. W . Salaman, Thomas M. Donegan and Andrés M. Cuervo Cotinga 12 (1999): 29– 39 En el marco de dos expediciones biológicos y Anglo-Colombian conservation expeditions — ‘Co conservacionistas anglo-colombianas multi-taxa, s lombia ‘98’ and the ‘Colombian EBA Project’. Seven llevaron a cabo relevamientos de aves en lo Serranía study sites were investigated using non-systematic de los Churumbelos, Cauca, en julio-agosto 1988, y observations and standardised mist-netting tech julio 1999. Se estudiaron siete sitios enter en 350 y niques by the three authors, with Dan Davison and 2500 m, con 421 especes registrados. Presentamos Liliana Dávalos in 1998. Each study site was situ un resumen de los especes raros para cada sitio, ated along an altitudinal transect at c. 300- incluyendo los nuevos registros de distribución más m elevational steps, from 350–2500 m on the Ama significativos. Los resultados estabilicen firme lo zonian slope of the Serranía. Our principal aim was prioridad conservacionista de lo Serranía de los to allow comparisons to be made between sites and Churumbelos, y aluco nos encontramos trabajando with other biological groups (mammals, herptiles, junto a los autoridades ambientales locales con insects and plants), and, incorporating geographi cuiras a lo protección del marcizo. cal and anthropological information, to produce a conservation assessment of the region (full results M e th o d s in Salaman et al.4). A sizeable part of eastern During 14 July–17 August 1998 and 3–22 July 1999, Cauca — the Bota Caucana — including the 80-km- ornithological surveys were undertaken in Serranía long Serranía de los Churumbelos had never been de los Churumbelos, Department of Cauca, by two subject to faunal surveys. -

Zootaxa, a New Genus for Three Species of Tyrant Flycatchers (Passeriformes: Tyrannidae)

Zootaxa 2290: 36–40 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new genus for three species of tyrant flycatchers (Passeriformes: Tyrannidae), formerly placed in Myiophobus JAN I. OHLSON1, JON FJELDSÅ2 & PER G. P. ERICSON3 1) Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden. Email: [email protected] 2) Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. Email: [email protected] 3) Director of Science, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden. Email: [email protected] Abstract A new genus, Nephelomyias, is erected for three species of Andean tyrant flycatchers (Aves: Passeriformes: Tyrannidae) traditionally placed in the genus Myiophobus. An extensive study based on molecular data has shown that they form a well supported clade that is not closely related to other Myiophobus species. Instead, they form a small independent lineage in Tyrannidae, together with Pyrrhomyias, Hirundinea and Myiotriccus. Key words: Nephelomyias lintoni, Nephelomyias ochraceiventris, Nephelomyias pulcher, Tyrannidae, taxonomy, phylogeny Introduction Recent phylogenetic studies, based on extensive molecular data (e.g. Ohlson et al. 2008; Tello et al. 2009), have greatly improved our knowledge of the relationships and evolution of the tyrant flycatchers (Tyrannidae). Several unexpected relationships have been revealed and a number of traditional genera have proven to be non-monophyletic, prompting taxonomic rearrangements. Here we erect a new generic name for three species traditionally placed in the genus Myiophobus, which were found by Ohlson et al. -

COLOMBIA 2019 Ned Brinkley Departments of Vaupés, Chocó, Risaralda, Santander, Antioquia, Magdalena, Tolima, Atlántico, La Gu

COLOMBIA 2019 Ned Brinkley Departments of Vaupés, Chocó, Risaralda, Santander, Antioquia, Magdalena, Tolima, Atlántico, La Guajira, Boyacá, Distrito Capital de Bogotá, Caldas These comments are provided to help independent birders traveling in Colombia, particularly people who want to drive themselves to birding sites rather than taking public transportation and also want to book reservations directly with lodgings and reserves rather than using a ground agent or tour company. Many trip reports provide GPS waypoints for navigation. I used GoogleEarth/ Maps, which worked fine for most locations (not for El Paujil reserve). I paid $10/day for AT&T to hook me up to Claro, Movistar, or Tigo through their Passport program. Others get a local SIM card so that they have a Colombian number (cheaper, for sure); still others use GooglePhones, which provide connection through other providers with better or worse success, depending on the location in Colombia. For transportation, I used a rental 4x4 SUV to reach places with bad roads but also, in northern Colombia, a subcompact rental car as far as Minca (hiked in higher elevations, with one moto-taxi to reach El Dorado lodge) and for La Guajira. I used regular taxis on few occasions. The only roads to sites for Fuertes’s Parrot and Yellow-eared Parrot could not have been traversed without four-wheel drive and high clearance, and this is important to emphasize: vehicles without these attributes would have been useless, or become damaged or stranded. Note that large cities in Colombia (at least Medellín, Santa Marta, and Cartagena) have restrictions on driving during rush hours with certain license plate numbers (they base restrictions on the plate’s final numeral). -

A Comprehensive Species-Level Molecular Phylogeny of the New World

YMPEV 4758 No. of Pages 19, Model 5G 2 December 2013 Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution xxx (2013) xxx–xxx 1 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev 5 6 3 A comprehensive species-level molecular phylogeny of the New World 4 blackbirds (Icteridae) a,⇑ a a b c d 7 Q1 Alexis F.L.A. Powell , F. Keith Barker , Scott M. Lanyon , Kevin J. Burns , John Klicka , Irby J. Lovette 8 a Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, and Bell Museum of Natural History, University of Minnesota, 100 Ecology Building, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 9 55108, USA 10 b Department of Biology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182, USA 11 c Barrick Museum of Natural History, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154, USA 12 d Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14950, USA 1314 15 article info abstract 3117 18 Article history: The New World blackbirds (Icteridae) are among the best known songbirds, serving as a model clade in 32 19 Received 5 June 2013 comparative studies of morphological, ecological, and behavioral trait evolution. Despite wide interest in 33 20 Revised 11 November 2013 the group, as yet no analysis of blackbird relationships has achieved comprehensive species-level sam- 34 21 Accepted 18 November 2013 pling or found robust support for most intergeneric relationships. Using mitochondrial gene sequences 35 22 Available online xxxx from all 108 currently recognized species and six additional distinct lineages, together with strategic 36 sampling of four nuclear loci and whole mitochondrial genomes, we were able to resolve most relation- 37 23 Keywords: ships with high confidence. -

Costa Rica: the Introtour | July 2017

Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica: The Introtour | July 2017 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour Costa Rica: The Introtour July 15 – 25, 2017 Tour Leader: Scott Olmstead INTRODUCTION This year’s July departure of the Costa Rica Introtour had great luck with many of the most spectacular, emblematic birds of Central America like Resplendent Quetzal (photo right), Three-wattled Bellbird, Great Green and Scarlet Macaws, and Keel-billed Toucan, as well as some excellent rarities like Black Hawk- Eagle, Ochraceous Pewee and Azure-hooded Jay. We enjoyed great weather for birding, with almost no morning rain throughout the trip, and just a few delightful afternoon and evening showers. Comfortable accommodations, iconic landscapes, abundant, delicious meals, and our charismatic driver Luís enhanced our time in the field. Our group, made up of a mix of first- timers to the tropics and more seasoned tropical birders, got along wonderfully, with some spying their first-ever toucans, motmots, puffbirds, etc. on this trip, and others ticking off regional endemics and hard-to-get species. We were fortunate to have several high-quality mammal sightings, including three monkey species, Derby’s Wooly Opossum, Northern Tamandua, and Tayra. Then there were many www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica: The Introtour | July 2017 superb reptiles and amphibians, among them Emerald Basilisk, Helmeted Iguana, Green-and- black and Strawberry Poison Frogs, and Red-eyed Leaf Frog. And on a daily basis we saw many other fantastic and odd tropical treasures like glorious Blue Morpho butterflies, enormous tree ferns, and giant stick insects! TOP FIVE BIRDS OF THE TOUR (as voted by the group) 1. -

Peru: from the Cusco Andes to the Manu

The critically endangered Royal Cinclodes - our bird-of-the-trip (all photos taken on this tour by Pete Morris) PERU: FROM THE CUSCO ANDES TO THE MANU 26 JULY – 12 AUGUST 2017 LEADERS: PETE MORRIS and GUNNAR ENGBLOM This brand new itinerary really was a tour of two halves! For the frst half of the tour we really were up on the roof of the world, exploring the Andes that surround Cusco up to altitudes in excess of 4000m. Cold clear air and fantastic snow-clad peaks were the order of the day here as we went about our task of seeking out a number of scarce, localized and seldom-seen endemics. For the second half of the tour we plunged down off of the mountains and took the long snaking Manu Road, right down to the Amazon basin. Here we traded the mountainous peaks for vistas of forest that stretched as far as the eye could see in one of the planet’s most diverse regions. Here, the temperatures rose in line with our ever growing list of sightings! In all, we amassed a grand total of 537 species of birds, including 36 which provided audio encounters only! As we all know though, it’s not necessarily the shear number of species that counts, but more the quality, and we found many high quality species. New species for the Birdquest life list included Apurimac Spinetail, Vilcabamba Thistletail, Am- pay (still to be described) and Vilcabamba Tapaculos and Apurimac Brushfnch, whilst other montane goodies included the stunning Bearded Mountaineer, White-tufted Sunbeam the critically endangered Royal Cinclodes, 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Peru: From the Cusco Andes to The Manu 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com These wonderful Blue-headed Macaws were a brilliant highlight near to Atalaya. -

Spatuletails, Owlet Lodge & More 2018

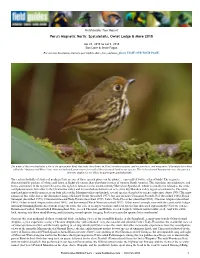

Field Guides Tour Report Peru's Magnetic North: Spatuletails, Owlet Lodge & More 2018 Jun 23, 2018 to Jul 5, 2018 Dan Lane & Jesse Fagan For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. The name of this tour highlights a few of the spectacular birds that make their homes in Peru's northern regions, and we saw these, and many more! This might have been called the "Antpittas and More" tour, since we had such great views of several of these formerly hard-to-see species. This Ochre-fronted Antpitta was one; she put on a fantastic display for us! Photo by participant Linda Rudolph. The eastern foothills of Andes of northern Peru are one of those special places on the planet… especially if you’re a fan of birds! The region is characterized by pockets of white sand forest at higher elevations than elsewhere in most of western South America. This translates into endemism, and hence our interest in the region! Of course, the region is famous for the award-winning Marvelous Spatuletail, which is actually not related to the white sand phenomenon, but rather to the Utcubamba valley and its rainshadow habitats (an arm of the dry Marañon valley region of endemism). The white sand endemics actually span areas on both sides of the Marañon valley and include several species described to science only since about 1976! The most famous of this collection is the diminutive Long-whiskered Owlet (described 1977), but also includes Cinnamon Screech-Owl (described 1986), Royal Sunangel (described 1979), Cinnamon-breasted Tody-Tyrant (described 1979), Lulu’s Tody-Flycatcher (described 2001), Chestnut Antpitta (described 1987), Ochre-fronted Antpitta (described 1983), and Bar-winged Wood-Wren (described 1977). -

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS Departamento De Zoología Y Antropología Física

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS Departamento de Zoología y Antropología Física TESIS DOCTORAL Diversidad y especificidad de simbiontes en aves neotropicales Diversity and host specificity of symbionts in neotropical birds MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Michaël André Jean Moens Directores Javier Pérez Tris Laura Benítez Rico Madrid, 2017 © Michaël André Jean Moens, 2016 Diversidad y Especificidad de Simbiontes en Aves Neotropicales (Diversity and Host Specificity of Symbionts in Neotropical birds.) Tesis doctoral de: Michaël André Jean Moens Directores : Javier Pérez Tris Laura Benítez Rico Madrid, 2016 © Michaël André Jean Moens, 2016 Cover Front Chestnut-breasted Coronet (Boissoneaua matthewsii) Taken at the San Isidro Reserve, Ecuador. Copyright © Jaime Culebras Cover Back Royal Flycatcher (Onychorhynchus coronatus) Taken at the Nouragues Reserve, French Guiana. Copyright © Borja Milá UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ZOOLOGÍA Y ANTROPOLOGÍA FÍSICA Diversidad y Especificidad de Simbiontes en Aves Neotropicales (Diversity and Host Specificity of Symbionts in Neotropical birds.) Tesis doctoral de: Michaël André Jean Moens Directores: Javier Pérez Tris Laura Benítez Rico Madrid, 2016 © Michaël André Jean Moens, 2016 UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ZOOLOGÍA Y ANTROPOLOGÍA FÍSICA Diversidad y Especificidad de Simbiontes en Aves Neotropicales (Diversity and Host Specificity of Symbionts -

Wildlife Ecology Provincial Resources

MANITOBA ENVIROTHON WILDLIFE ECOLOGY PROVINCIAL RESOURCES !1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank: Olwyn Friesen (PhD Ecology) for compiling, writing, and editing this document. Subject Experts and Editors: Barbara Fuller (Project Editor, Chair of Test Writing and Education Committee) Lindsey Andronak (Soils, Research Technician, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) Jennifer Corvino (Wildlife Ecology, Senior Park Interpreter, Spruce Woods Provincial Park) Cary Hamel (Plant Ecology, Director of Conservation, Nature Conservancy Canada) Lee Hrenchuk (Aquatic Ecology, Biologist, IISD Experimental Lakes Area) Justin Reid (Integrated Watershed Management, Manager, La Salle Redboine Conservation District) Jacqueline Monteith (Climate Change in the North, Science Consultant, Frontier School Division) SPONSORS !2 Introduction to wildlife ...................................................................................7 Ecology ....................................................................................................................7 Habitat ...................................................................................................................................8 Carrying capacity.................................................................................................................... 9 Population dynamics ..............................................................................................................10 Basic groups of wildlife ................................................................................11