Development and Use of Defatted Peanut Flours, Meals, and Grits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ffects of Peanut Grits and Peanut Flour on Quality of Muffins

~FFECTS OF PEANUT GRITS AND PEANUT FLOUR ON QUALITY OF MUFFINS By NING-BIN KUO 'I Bachelor of Science in Home Economics Texas A & I University Kingsville, Texas 1978 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE July, 1980 EFFECTS OF PEANUT GRITS AND PEANUT FLOUR ON QUALITY OF MUFFINS Thesis Approved: Thesis Adviser ~~n- ii 1062960 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS · The author wishes to express her thanks and appreciation to her major adviser, Dr. Lea L. Ebro, for her patience, guidance, and as sistance throughout this study. Sincere appreciation is also expressed to my graduate corrmittee: Dr. Esther A. Winterfeldt and Miss Hazel Baker, for their encourage ment and support; and to Dr. J. Leroy Folks, for his invaluable as sistance in the research design and data analyses of this Study. Thanks are also expressed to the seven attribute panel members, for their cooperation and support. Without them, this study would not have been possible. A note of appreciation is extended to Jean Shipman, for the muffin photographs. Special recognition is due to Gold Kist, Inc. of Atlanta, Georgia, and Southern Regional Research Center, USDA, New Orleans, Louisiana, for providing the peanut grits and peanut flour samples. Finally, special thanks and appreciation are given to my parents, Mr. and Mrs. Dod-yu Kuo, and my husband, Geng-Hwa Lin, for their understanding, constant encouragement, and inspiration. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION. 1 Purpose and Objectives • 3 Hypotheses . 3 Assumptions .•• 4 Limitations ••••.••• 4 Definitions .•••..•••• 4 II. -

Development of Peanut Flour Based Value Added Products for Malnourished Children

International Journal of Medical Sciences Volume 6 | Issue 2 | October, 2013 | 59-64 RESEARCH PAPER Development of Peanut Flour Based Value Added Products for Malnourished Children PAYAL BANSAL AND ANITA KOCHHAR See end of the paper for ABSTRACT : Protein energy malnutrition is the major concern of nutrition. Malnutrition is an underlying cause authors’ affiliation of death of 2.6 million children each year – one-third of the global total of children’s deaths. Partially defatted Correspondence to : peanut flour, is a protein-rich, inexpensive and underutilized product that offers the same health and dietary benefits PAYAL BANSAL of peanut with less fat and can be utilized for making value added products to eradicate malnutrition among children. Department of Food and Nutrition, Punjab Agricultural It was prepared by crushing roasted peanuts to extract oil and then grinding the left over meal into flour. Partially University, LUDHIANA defatted peanut flour was blended with cereals and pulses for making five value added products and were evaluated (PUNJAB) INDIA for sensory quality by using nine point hedonic scale and nutritional composition by using standard methods. The Email: bansal.payal19@gmail. acceptable percentage of peanut flour was 5% for soup, 10% for pancake, kheer and 30% for vadiya and papad. com Overall acceptability score was 7.2, 8.14, 8.51, 8.12 and 8.4. The developed products were found to be highly nutritious as soup gives 336.39 Kcal of energy, 14.53% protein, 692.73 mg calcium and 9.15 mg of iron. Pancake gives 458.53 Kcal of energy, 22.75% of protein, calcium 56.00 mg and iron 4.84 mg per100g. -

TOTAL FOLATE in PEANUTS and PEANUT PRODUCTS by LAKSHMI

TOTAL FOLATE IN PEANUTS AND PEANUT PRODUCTS by LAKSHMI KOTA (Under the Direction of Ronald R. Eitenmiller) ABSTRACT Samples consisting of 222 cultivar specific samples of four different peanut types (Runner, Virginia, Spanish and Valencia) from 2 years (2005 and 2006) from 3 geographical locations (Southeast, Southwest and Virginia/Carolina) were collected for the study. No significant differences were noted among the folate levels by types for 2005 crop year peanuts (P>0.05). For 2006 peanuts, Spanish peanuts were statistically lower in folate than Runner and Virginia peanuts (P<0.05). For the Runner cultivars, significant (P<0.05) differences existed among cultivars with some significant year-to-year variation. Year of harvest did not have significant effect on folate content of Virginia peanuts. Folate contents among Virginia cultivars were statistically similar in 2005 and 2006. For Spanish cultivars in 2005, OLin had significantly higher folate than Tamspan 90. Overall means for both Runner and Spanish peanut types showed that high-oleic cultivars contained significantly higher total folate levels than normal cultivars (P<0.05). Folate levels in peanuts from Virginia/Carolina region varied significantly by production year, but peanuts from Southeast and Southwest region did not vary from 2005 to 2006. Response surface methodology (RSM) was used to optimize the trienzyme digestion for the extraction of total folate from peanut butter. The predicted second-order polynomial model was adequate (R 2 = 0.97) with a small coefficient of variation (3.05). Both Pronase R and conjugase had significant effects on the extraction. Ridge analysis gave an optimum trienzyme time: Pronase R, 1h; α-amylase, 1.5 h; conjugase, 1h. -

Formulation and Evaluation of Peanut Flour Incorporated Cookies

International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition ISSN: 2455-4898 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.14 www.foodsciencejournal.com Volume 3; Issue 5; September 2018; Page No. 56-59 Formulation and evaluation of peanut flour incorporated cookies Reena Singh1, Arivuchudar R2 1 Department of Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics, Periyar University, Salem, Tamil Nadu, India 2 Assistant professor, Department of Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics, Periyar University, Salem, Tamil Nadu, India Abstract Peanuts, largely accepted and affordable nut and oil seed, is well–known for its nutrients density. The protein, MUFA, iron and niacin are found in abundance and has various potential health benefits, including growth promotion and overpowering PCOS and infertility. The implication of value addition to the customarily celebrated snack product lies in the nutritional augmentation of a large community with great ease. Hence, this study is planned with the objective of incorporating the wellness of roasted peanut flour into the refined wheat flour and developing value added cookies, as it is a widely accepted food product by all age groups, with relatively long shelf life and convenient storage. The developed value-added cookies were subjected to nutrient evaluation and compared with the control. Keywords: value addition, peanut, roasting Introduction Objectives There is a perceptible variance in the intake design of peanut The study is framed with the following objectives: both in the developed and developing countries. Most of the a) To develop the peanut flour from roasted peanut. peanut produced in the developing countries is exhausted for b) To formulate cookies by incorporating peanut flour in oil extraction required to meet the domestic needs, while in various proportions. -

Peanut As a Source of Protein for Human Foods

PlantFoodsfor Human Nutrition 41: 165-177, 1991. '' " *i 165 © 1991 Kluwer Academic Pablishers. Printe4 in the Netherlands. Peanut as a source of protein for human foods B. SINGH & U. SINGH' Department of Food Science, Alabama A & Al University. Normal, AL 35762, USA ('present address. International Crops Research Institutefor Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT). Patancherv,A.P., India) Received 25 August 1990; accepted with minor revisions I November 1990 Key words: peanut, peanut protein, peanut fortified foods Abstract. Peanut has traditionally been used as asource of oil; however, its worldwide annual protein harvest has reached neariy 4 5 million ton3 . India followed by China and the United States are the major producers of peanut. In recent years, several cereals and legumes-based foods using peanuts as protein supplements have been developed to alleviate protein calories malnutrition problem. Peanut in the form of flour, protein isolates, and meal in a nxed product have been found to be very desirable from a sensory quality point of view. Peanut protein is deficient with rcspect to certain essertial amino acids, but its true digestibility is comparabL with that of animal protein. Even though various processing methods influence the nutritional and sensory quality of peanut fortified human foods available information on these aspects have been reviewed and summarised in this paper in order to optimize the utilization of peanut protein to increase protein value of cereal-based foods in developing countries of the peanut growing regions of the world. Introduction Food crops have occupied an important place in human nutrition as they remain the major sources of calories and proteins for a large proportion of the world population, particularly, in the developing countries. -

Defatted Peanut) Flour Cookies

JOURNAL OF GRAIN PROCESSING AND STORAGE Journal homepage: www.jakraya.com/journal/jgps ORIGINAL ARTICLE Nutritional and Functional Characterization of Peanut Okara (Defatted Peanut) Flour Cookies Trushal Dharsenda 1, Mukesh Dabhi 1, M. Jethva 1 and M. Kapopara 2 1Department of Processing and Food Engineering, College of Agricultural Engineering and Technology, 2Bakery School, Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh-362001, Gujarat, India. Abstract Peanut is the most important oil seed in the world, and rapidly becoming a valuable source of plant protein. The oil can be removed from *Corresponding Author: peanut, the protein could be concentrated from residual cakes and this cake was known as peanut okara. Peanut okara was used for the preparation of Mukesh Dabhi nutritional protein rich cookies. In this study the mixing ratios of refined wheat flour and peanut okara flour were 100:00 (Control), 90:10 Email: [email protected] (Treatment T1), 80:20 (Treatment T2), 70:30 (Treatment T3), 60:40 (Treatment T4), 50:50 (Treatment T5) respectively. The nutritional characteristics in terms of moisture content, protein, total ash, fat content Received: 03/12/2015 and carbohydrates of cookies were increase with increases peanut okara Revised: 24/12/2015 flour with refined wheat flour. The functional properties i.e. Water Absorption Index and Water Solubility Index of cookies were increase with Accepted: 29/12/2015 increases proportion of peanut okara flour. Cookies versatility, long shelf life, availability in numerous shapes and sizes, high digestibility, good nutrition, and relatively low cost are attractive to the consumer. Keywords: Cookies, Nutritional Characteristics, Functional Characteristics, Peanut Okara, Defatted Peanut. 1. -

OPTIMIZATION and ACCEPTABILITY of MEATLESS CHICKEN NUGGET ANALOGS PREPARED from TEXTURED PEANUT by YONG, YEE SHYEN Bachelor Of

OPTIMIZATION AND ACCEPTABILITY OF MEATLESS CHICKEN NUGGET ANALOGS PREPARED FROM TEXTURED PEANUT By YONG, YEE SHYEN Bachelor of Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2003 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE July, 2006 OPTIMIZATION AND ACCEPTABILITY OF MEATLESS CHICKEN NUGGET ANALOGS PREPARED FROM TEXTURED PEANUT Thesis Approved: Dr. Margaret J. Hinds Thesis Adviser Dr. Carla Goad Dr. Christina DeWitt Dr. William McGlynn Dr. A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This page is dedicated to everyone who has somehow laid a print in my life both directly involved in this research and those who stand by the sidelines cheering me on towards the end. First of all, thank you God for bringing me to form and giving me talents that are limited only by my own imagination. Dr. Margaret Hinds, thank you for your generous support, optimistic attitude, constructive guidance, and undying understanding. My committee members: Dr. Christina DeWitt, Dr. Carla Goad and Dr. William McGlynn for their expertise and suggestion that helped me improve this research. Thank you Mum and Dad for your sacrifices to put me through college. My sister, aunts and Kenneth for being the cheerleading squad. David Moe, Darren Scott, Renee Albers-Nelson, Joan Summer and employees of the Food and Ag Products Research and Technology Center for guidance and valuable inputs. Also a note of appreciation to all my colleagues: Shamira Fernandes, Dharmendra Bangalore and Fadi Al Jorf for their friendships and the wonderful memories. -

Isolation of Protein from Defatted Peanut Meal and Characterize Their Nutritional Profile

Chemistry Research Journal, 2018, 3(2):187-196 Available online www.chemrj.org ISSN: 2455-8990 Research Article CODEN(USA): CRJHA5 Isolation of Protein from Defatted Peanut Meal and Characterize their Nutritional Profile Md. S Uddin1, Md A Islam1, Mohammad M Rahman2, M. B Uddin1, Md. Anisur R Mazumder1* 1Department of Food Technology and Rural Industries, Faculty of Agricultural Engineering & Technology, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh 2202, Bangladesh 2Department of Family Planning, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, People’s Republic of Bangladesh Abstract Peanut contains high amount of protein (26%) and protein content increased in the groundnut meal after extraction of oil from it. The proximate analysis defatted peanut meal indicated that it contains 47–55% high quality protein. Peanut protein was isolated from defatted peanut meal by alkaline isoelectric precipitation and physical separation procedures. Peanut protein isolates had a solubility profile similar to that of peanut flour, with minimum solubility observed at pH 3.5–4.5 and maximum solubility at pH 10 and higher. Roasting of peanut reduced all functional properties of defatted peanut flour. Results suggested that peanut protein isolates could be used in food formulations, but would not be suitable for applications requiring high water retention and foaming capacity. It could be a good source of protein fortification for a variety of food products for protein deficient consumers in developing countries as well as a functional ingredient for the peanut industry. The production of peanut protein isolates could also add value to defatted peanut flour, a low value by-product of peanut oil production. Keywords peanut, protein, isolation, solubility, nutrition 1. -

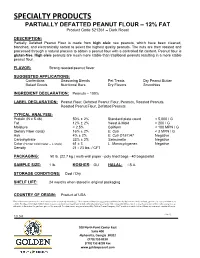

SPEC Partially Defatted Peanut Flour

SPECIALTY PRODUCTS PARTIALLY DEFATTED PEANUT FLOUR – 12% FAT Product Code 521261 – Dark Roast DESCRIPTION: Partially Defatted Peanut Flour is made from high oleic raw peanuts, which have been cleaned, blanched, and electronically sorted to select the highest quality peanuts. The nuts are then roasted and processed through a natural process to obtain a peanut flour with a controlled fat content. Peanut flour is gluten-free. High oleic peanuts are much more stable than traditional peanuts resulting in a more stable peanut flour. FLAVOR: Strong roasted peanut flavor SUGGESTED APPLICATIONS: Confections Seasoning Blends Pet Treats Dry Peanut Butter Baked Goods Nutritional Bars Dry Flavors Smoothies INGREDIENT DECLARATION: Peanuts – 100% LABEL DECLARATION: Peanut Flour, Defatted Peanut Flour, Peanuts, Roasted Peanuts, Roasted Peanut Flour, Defatted Peanuts TYPICAL ANALYSIS: Protein (N x 5.46) 50% ± 2% Standard plate count < 5,000 / G Fat 12% ± 2% Yeast & Mold < 200 / G Moisture < 2.5% Coliform < 100 MPN / G Dietary Fiber (total) 16% ± 2% E. Coli < 3 MPN / G Ash 4% ± 2% E. Coli O157:H7 Negative Carbohydrate 33% ± 2% Salmonella Negative Color (Hunter colorimeter – L scale) 61 ± 3 L. Monocytogenes Negative Density 21 - 23 lbs. / CFT PACKAGING: 50 lb. (22.7 kg.) multi-wall paper - poly lined bags - 40 bags/pallet SAMPLE SIZE: 1 lb. KOSHER: OU HALAL: I.S.A. STORAGE CONDITIONS: Cool / Dry SHELF LIFE: 24 months when stored in original packaging. COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: Product of USA This information contained herein is correct to the best of our knowledge. The recommendations or suggestions contained in this bulletin are made without guarantee or representation as to results. -

Nutritional Facts Landies Candies

NUTRITIONAL FACTS LANDIES CANDIES Landies Candies Pretzel Munch Tree Box Nutritional Facts Milk Chocolate White Cookies Milk Chocolate Serving Size: 1.5 oz (42g) Peanut Butter & Cream Butterfinger Pretzel Munch Pretzel Munch Pretzel Munch Serving Size Per Package: 2 % % % Amt. Per Daily Amt. Per Daily Amt. Per Daily Serving Value Serving Value Serving Value Calories 210 210 200 Calories from Fat 90 80 80 Total Fat 10g 15% 8g 12% 9g 14% Saturated Fat 6g 30% 7g 35% 5g 25% Trans Fat 0g 0g 0g Cholesterol <5mg 2% 0mg 0% <5mg 2% Sodium 85mg 4% 110mg 4% 80mg 3% Total Carbohydrate 27g 9% 30g 10% 27g 9% Dietary Fiber 1g 4% 1g 4% 1g 4% Sugar 16g 19g 16g Protein 3g 2g 3g Vitamin A 2% 0% 0% Vitamin C 0% 0% 0% Calcium 6% 0% 6% Iron 6% 4% 6% Percent Daily Value are based on a 2,000 calorie diet. Your Daily values may be higher or lower depending on your calorie needs. MILK CHOCOLATE PEANUT BUTTER PRETZEL MUNCH (Net Wt. 3oz.) Ingredients: Milk Chocolate (Sugar, Milk, Cocoa Butter, Chocolate Liquor, Soy Lecithin [an emulsifier], Vanilla), Pretzel (Enriched Flour [Wheat Flour, Niacin, Reduced Iron, Thiamine Mononitrate, Riboflavin, Folic Acid], Water, Canola Oil, Salt, Malt, Yeast, Baking Soda), Peanut Butter Chips (Sugar, Partially Hydrogenated Palm Kernel 0il, Partially Defatted Peanut Flour, Nonfat Milk Powder, Whey Powder, Peanut Butter [Peanuts, Hydrogenated Rapeseed and Cotton Oil], Dextrose, Salt and Soy Lecithin [an emulsifier]), Peanuts (Roasted in Peanut Oil and Salted), White Drizzle (Sugar, Palm Kernel Oil and Partially Hydrogenated Palm Kernel Oil, Reduced Mineral Whey Powder, Whole Milk, Natural Dry Milk, Soy Lecithin [an emulsifier], Salt, Vanillin [an artificial flavor]). -

The Outlook for Processing Peanut Meal Into Edible Products in Georgia

t • THE OUTLOOK FOR PROCESSING PEANUT MEAL INTO EDIBLE PRODUCTS IN GEORGIA by Tze I. Chiang ENGINEERING EXPERIMENT STATION Industrial Development Division Georgia Institute of Technology Project E-400-902 THE OUTLOOK FOR PROCESSING PEANUT MEAL INTO EDIBLE PROTEIN PRODUCTS IN GEORGIA by Tze I. Chiang ENGINEERING EXPERIMENT STATION Industrial Development Division Georgia Institute of Technology June 1973 Table of Contents Page Acknowledgments Summary ii INTRODUCTION 1 WHY CONSIDER PROCESSING PEANUT MEAL FOR EDIBLE PROTEIN PRODUCTS IN GEORGIA? 2 THE MARKET POTENTIALS OF EDIBLE PEANUT PROTEIN PRODUCTS 5 Peanut Proteins and Soy Proteins 5 End Uses and Market Potentials 7 Current Sales of Peanut Protein Products 12 PROCESSING PEANUT PROTEIN PRODUCTS 13 Source Materials and Sanitary Requirements 13 Production Processes 14 A Milling Unit within a Peanut Crushing Plant 18 RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT NEEDS 19 REFERENCES 21 Tables 1. Analysis of Peanut Flour and Soy Flour 6 2. Comparison of Essential Amino Acid Levels in FAO Reference Protein and Proteins of Peanut, Soybean, and Skim Milk 7 3. Estimated U. S. Production of Soy Protein Foods, 1970 9 4. Projected Impact of Soy Protein Substitution in Pounds of Meat, Kind, and Estimated Percent of Meat Replaced in the United States, 1980 11 Acknowledgments The author wishes to express his appreciation to all persons who have of- fered their time and information to help make this report possible. Although it is impossible to list all, credit to major sources is given below: Mr. Ron Balkcom of the Georgia Agricultural Commodity Commission for Pea- nuts, Tifton, Georgia, has been actively promoting the uses and processing of peanut protein products. -

Ingredient Statement Frozen Yogurt

Ingredient Statement Frozen Yogurt NONTART FROZEN YOGURT (nonfat milk, sugar, nonfat yogurt [pasteurized nonfat milk, starch, live and active cultures] or [pasteurized nonfat milk, pectin, live and active cultures], nonfat yogurt powder [nonfat milk, culture], dextrose, carrageenan, guar gum, maltodextrin, mono- and diglycerides, rice starch), CHOCOLATE CHIP COOKIES (unbleached enriched flour [wheat flour, Chocolate Chip Cookie Frozen Yogurt niacin, reduced iron, thiamine mononitrate [vitamin B1], riboflavin [vitamin B2], folic acid], semisweet chocolate chips [sugar, chocolate, cocoa butter, dextrose, soy lecithin], sugar, soybean oil, partially hydrogenated cottonseed oil, high fructose corn syrup, leavening [baking soda, ammonium phosphate], salt, whey [from milk], natural and artificial flavor, caramel color) NONTART FROZEN YOGURT (nonfat milk, sugar, nonfat yogurt [pasteurized nonfat milk, starch, live and active cultures] or [pasteurized nonfat milk, pectin, live and active cultures], nonfat yogurt powder [nonfat milk, culture], dextrose, carrageenan, guar Chocolate Hazelnut Frozen Yogurt gum, maltodextrin, mono- and diglycerides, rice starch), CHOCOLATE HAZELNUT (sugar, palm oil, hazelnuts, cocoa, skim milk, reduced mineral whey [milk], soy lecithin [emulsifier], vanillin [artificial flavor]) NONTART FROZEN YOGURT (nonfat milk, sugar, nonfat yogurt [pasteurized nonfat milk, starch, live and active cultures] or [pasteurized nonfat milk, pectin, live and active cultures], nonfat yogurt powder [nonfat milk, culture], dextrose, carrageenan,