June 15, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senator Joe Scarnati, President Pro Tempore

SENATE LEADERSHIP 2019-2020 Senator Joe Scarnati, President Pro Tempore As President Pro Tempore of the Senate, he holds the third-highest constitutional office in the State. He was born and raised in Brockway, Pennsylvania and represents the 25th Senatorial District, which includes Cameron, Clinton, Elk, Jefferson, McKean, Potter and Tioga Counties and portions of Clearfield County. Joe grew up understanding that business and industry are vital to our state’s economy and its future. After graduating from Penn State University at DuBois, Joe became a third-generation business owner in the Brockway area. He has carried on the lifelong tradition of working to better his community through involvement and civic leadership, serving on both the Brockway Borough Council and the Jefferson County Development Council. He is also a member of the St. Tobias Roman Catholic Church in Brockway. Working in the private sector for 20 years prior to coming to Harrisburg, serving as a local official and being a small business owner have given him a unique perspective on how government can work more effectively to help job-creators, working families and communities. Since being elected to office, Joe has been a leader in reforming the way business is conducted in Harrisburg, and he remains committed to making the institution more open and accessible to the citizens of the Commonwealth. As Senate President Pro Tempore, Joe serves as an ex-officio member of each of the 22 Senate Committees. He has been a committed leader in addressing numerous important fiscal and conservative issues within the state. In his 17 years as a State Senator, Joe has served as a rank and file member of the Senate, as a member of Senate Leadership and currently as Senate President Pro Tempore – a position that he was elected to by the full Senate. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography

THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY VOLUME CXXXVI October 2012 NO. 4 EDITORIAL Tamara Gaskell 329 INTRODUCTION Daniel P. Barr 331 REVIEW ESSAY:DID PENNSYLVANIA HAVE A MIDDLE GROUND? EXAMINING INDIAN-WHITE RELATIONS ON THE EIGHTEENTH- CENTURY PENNSYLVANIA FRONTIER Daniel P. Barr 337 THE CONOJOCULAR WAR:THE POLITICS OF COLONIAL COMPETITION, 1732–1737 Patrick Spero 365 “FAIR PLAY HAS ENTIRELY CEASED, AND LAW HAS TAKEN ITS PLACE”: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE SQUATTER REPUBLIC IN THE WEST BRANCH VALLEY OF THE SUSQUEHANNA RIVER, 1768–1800 Marcus Gallo 405 NOTES AND DOCUMENTS:A CUNNING MAN’S LEGACY:THE PAPERS OF SAMUEL WALLIS (1736–1798) David W. Maxey 435 HIDDEN GEMS THE MAP THAT REVEALS THE DECEPTION OF THE 1737 WALKING PURCHASE Steven C. Harper 457 CHARTING THE COLONIAL BACKCOUNTRY:JOSEPH SHIPPEN’S MAP OF THE SUSQUEHANNA RIVER Katherine Faull 461 JOHN HARRIS,HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION, AND THE STANDING STONE MYSTERY REVEALED Linda A. Ries 466 REV.JOHN ELDER AND IDENTITY IN THE PENNSYLVANIA BACKCOUNTRY Kevin Yeager 470 A FAILED PEACE:THE FRIENDLY ASSOCIATION AND THE PENNSYLVANIA BACKCOUNTRY DURING THE SEVEN YEARS’WAR Michael Goode 472 LETTERS TO FARMERS IN PENNSYLVANIA:JOHN DICKINSON WRITES TO THE PAXTON BOYS Jane E. Calvert 475 THE KITTANNING DESTROYED MEDAL Brandon C. Downing 478 PENNSYLVANIA’S WARRANTEE TOWNSHIP MAPS Pat Speth Sherman 482 JOSEPH PRIESTLEY HOUSE Patricia Likos Ricci 485 EZECHIEL SANGMEISTER’S WAY OF LIFE IN GREATER PENNSYLVANIA Elizabeth Lewis Pardoe 488 JOHN MCMILLAN’S JOURNAL:PRESBYTERIAN SACRAMENTAL OCCASIONS AND THE SECOND GREAT AWAKENING James L. Gorman 492 AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY LINGUISTIC BORDERLAND Sean P. -

I &Lafiir J Nurnal

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA i &Lafiir j nurnal FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 2008 SESSION OF 2008 192ND OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY No. 66 SENATE The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The Chair thanks Reverend Bachman, who is the guest today of Senator Folmer and Senator FRIDAY, November 21, 2008 Robbins. The Senate met at 9:30 a.m., Eastern Standard Time. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE The PRESIDENT pro tempore (Joseph B. Scarnati III) in the (The Pledge of Allegiance was recited by those assembled.) Chair. SPECIAL ORDER OF BUSINESS PRAYER FAREWELL TO MEMBERS The Chaplain, Reverend RONALD BACHMAN, of Rexmont The PRESIDENT pro tempore. As a special order of business, E.C. Evangelical Congregational Church, Rexmont, offered the the Senate will now proceed with our tributes to our retiring following prayer: Members. The Chair recognizes the gentleman from Delaware, Senator Let us pray. Pileggi. Leading into my prayer, I want to just mention two pieces of Senator PILEGGI. Mr. President, today we are honoring a Scripture. From Matthew 12:35, it says, "A good man out of the remarkable group of people. They come from different back- treasure of the heart bringeth forth good things." From Proverbs grounds, including a dairy farmer, a surveyor, and veterans of 12:25, "Heaviness in the heart of man maketh it stoop, but a good military service. But they all have one thing in common: a pas- word maketh it glad." sion for serving the residents of their districts in this Common- Father God, we want to thank You for this day that You have wealth. All seven Members have made their districts better provided for us. -

Criminal No. 06-319-03

Case 2:06-cr-00319-RB Document 906 Filed 10/28/11 Page 1 of 89 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA : v. : CRIMINAL NO. 06-319-03 VINCENT J. FUMO : GOVERNMENT’S REPLY MEMORANDUM REGARDING RESENTENCING Case 2:06-cr-00319-RB Document 906 Filed 10/28/11 Page 2 of 89 Table of Contents I. Introduction.. 1 II. The New E-Mails. 3 A. Lack of Remorse. 7 B. Lack of Respect for Authority. 10 C. Blaming Ruth Arnao. 11 D. Settling Scores. 14 E. The Book. 17 F. Fumo’s Plans for the Future. 19 III. Fumo Addresses Few of the Sentencing Factors. 27 IV. Fumo is Not Entitled to a Downward Departure. 30 A. Age and Health. 32 1. Age. 34 2. Health. 35 B. Post-Offense Rehabilitation.. 54 V. Fumo Should Not Receive the Enormous Variance He Seeks. 57 A. Good Works and Public Service. 58 B. Validity of the Sentencing Guidelines. 68 1. The fraud guideline enjoys wide acceptance. 68 2. No case supports the variance requested by Fumo.. 74 VI. Fumo Should Be Ordered to Pay Full Restitution. 81 VII. Conclusion. 85 Case 2:06-cr-00319-RB Document 906 Filed 10/28/11 Page 3 of 89 I. Introduction. An explosive trove of e-mails obtained by the government during the past 10 days confirms an uncomfortable but inescapable truth: the benign portrayal of defendant Vincent J. Fumo provided in his memorandum regarding resentencing bears no relation to the actual person. The government just obtained voluminous e-mail correspondence from Fumo’s most recent six months in prison. -

Attorneys, Judges, Law Profes- Honolulu, Dallas and Chicago

® October 2006 The Monthly Newspaper of the Philadelphia Bar Association Vol. 35, No. 10 30th Street Station to Host Presenza 28th Andrew Hamilton Gala to Receive By Deborah R. Gross Brennan and Amy B. Ginensky Come celebrate Philadelphia with Honors the Philadelphia Bar Foundation at the newly revamped and sure-to- be-exciting Andrew Hamilton Gala. by Jeff Lyons The 28th annual event will take place on Saturday, Nov. 4 at 30th President Judge Louis J. Presenza of Street Station. Philadelphia Municipal Court has been The Hamilton Gala is the social selected as the recipient of the 2006 Justice event of the year for the Philadel- William J. Brennan Jr. phia legal community and it raises Distinguished Jurist thousands of dollars for grants to Award. The award will worthy local organizations. be presented at the And this year, it is going to be Association’s October different. Quarterly Meeting and The Foundation wants to cele- Luncheon on Oct. 30 at brate all things Philadelphian and 12 p.m. at the Park all the neighborhoods that make Hyatt Philadelphia at Presenza this city great. We have a crew of the Bellevue. people working on a décor design The award recognizes a jurist who ad- that will transform the North Wait- heres to the highest ideals of judicial ser- ing Room and South Arcade at 30th vice. Any member of the state or federal Street into the best and brightest of bench, whether active or retired, who has the City of Brotherly Love. made a significant, positive impact on the Think about it! When else, within quality or administration of justice in the space of a few minutes at a Philadelphia is eligible for consideration. -

Center City Quarterly

CENTER CITY QUARTERLY Newsletter of the Center City Residents' Association Vol. 2 No. 2 June 2011 Table of Contents No New Sleaze: CCRA Wins Reversal of No New Sleaze: CCRA Wins Reversal of Forum Theater Expansion ....................................1 Forum Theater Expansion President’s Report ...................................................3 By Adam Schneider, President, CCRA Annual Meeting .......................................................4 Down by the Sea ......................................................5 Why Olympia Matters ............................................7 A Job Well Done, Alex Klein .................................8 Every Inch a Classroom .........................................8 Circulars? No, Thanks ...........................................11 Run, Philly, Run .......................................................11 The Reinvention of Dilworth Plaza .................12 Public Art to Light Up the Plaza .......................13 Lenora Berson, An Army of One ......................15 Another Success for Freire Charter School ........................................................17 Census and the City ..............................................18 When a Bar Becomes a Nuisance ....................18 A Brighter Future for an Old Annex ................19 Klein's Korner ..........................................................20 Christensen Jt Be a House Detective: Look at Maps .............21 CCRA successfully prevented the owner of Les Gals (the double building on the right above) and the Forum Theater -

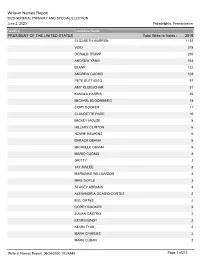

Write-In Names Report 2020 GENERAL PRIMARY and SPECIAL ELECTION June 2, 2020 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Write-in Names Report 2020 GENERAL PRIMARY AND SPECIAL ELECTION June 2, 2020 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Heading Candidate Name PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES Total Write-In Votes : 2515 ELIZABETH WARREN 1122 VOID 318 DONALD TRUMP 265 ANDREW YANG 163 BLANK 122 ANDREW CUOMO 103 PETE BUTTIGIEG 57 AMY KLOBUCHAR 31 KAMALA HARRIS 25 MICHAEL BLOOMBERG 18 CORY BOOKER 11 CLAUDETTE PAGE 10 MICKEY MOUSE 8 HILLARY CLINTON 6 HOWIE HAWKINS 6 BARACK OBAMA 5 MICHELLE OBAMA 5 MARIO CUOMO 4 GRITTY 3 JAY INSLEE 3 MARIANNE WILLIAMSON 3 MIKE DOYLE 3 STACEY ABRAMS 3 ALEXANDRIA OCASIO-CORTEZ 2 BILL GATES 2 COREY BOOKER 2 JULIAN CASTRO 2 KEVIN BUNDY 2 KEVIN TYAS 2 MARK CHARLES 2 MARK CUBAN 2 Write-in Names Report 06/24/2020 10:24AM Page 1 of212 Write-in Names Report 2020 GENERAL PRIMARY AND SPECIAL ELECTION June 2, 2020 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Heading Candidate Name MUMIA ABU JAMAL 2 NATHAN SCHMIDT 2 OLGA MELENDEZ 2 PHIL MURPHY 2 RAHIEM S BURGESS 2 REBECCA L ZARNOWSKI 2 VAZQUEZ EMILIO 2 ADAM SCHIFF 1 AL GORE 1 ALBERT BRAUN 1 ALI MUHAMMAD 1 ANDREW FELTON 1 ANDREW GREGORY MAZUR 1 ANDREW THOMAS 1 ANNA GREENE 1 ANNALEE MAUSKGAT 1 ANNE SMALL 1 ANTHONY S RATKA 1 ANTONIO LIEGGI 1 AYISHA ABDULALI 1 BART WEAVER 1 BERNIE BROGDEN 1 BERNIE SAMPSON 1 BOB CASEY 1 BOB STRAUSS 1 BRAD PITT 1 BREE O NEIL 1 BRIAN WRIGHT 1 BRUCE BRADLEY II 1 BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN 1 BRUCE WAYNE 1 CARL BRUTANANADILEWSKI 1 Write-in Names Report 06/24/2020 10:24AM Page 2 of212 Write-in Names Report 2020 GENERAL PRIMARY AND SPECIAL ELECTION June 2, 2020 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Heading Candidate Name -

First Amendment Lawyers Association

First Amendment Lawyers Association FALA 2017 Summer Meeting July 19, 2017 through July 22, 2017 @ Royal Sonesta Harbor Court, 550 Light St, Baltimore, MD 21202 Theme: The First Amendment - This is not a Safe Space: The Case for Free Speech and Debate in the Age of Thin Skin First Amendment Advocates and Attorneys often find themselves speaking up for the most controversial speakers, after all, the First Amendment is not meant to protect polite speech. In 2017, controversial speakers have been met with violence and outrage on college campuses and elsewhere. This summer’s meeting brings a blend of speakers that range from Free Speech Absolutists to speakers who see some forms of censorship as necessary. This meeting symbolizes the case for Free Speech and Debate, even among First Amendment advocates. Because we can’t expect others to tolerate people they don’t agree with, unless we have the ability to listen to some of our “opponents” ourselves. Wednesday, July 19, 2017 6:30 P.M. to 8:30 P.M. Please join us this evening to meet and mingle with friends and make new ones. Guests and family are welcome! Thursday, July 20, 2017 8:00 A.M. Breakfast (Guests Invited) 8:25 A.M. President’s Welcome 8:30 A.M. 1.0 Free Speech in Peril - the New Anti-Hate-Speech Law in Germany - Dr. Daniel Koetz Free Speech is targeted intensively in Germany. “Hate Speech” is the buzz word that lawmakers love to use to limit Free Speech, just as “Youth Protection” was a while back. -

Grassroots Organizing Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic

Grassroots Organizing Amid a Pandemic For the Nikil Saval campaign, grassroots organizing has persisted despite going fully digital. May 2020 By Liam Scott The key to grassroots organizing is supposed to be simple: knock on more doors, talk to more voters, earn more support. But in the age of coronavirus, volunteer networks for campaigns and initiatives across the country have been pushed off the streets and onto computer screens and cell phones. For some, this is a cause for concern. Others see this idle and focused time as a bonus for organizing efforts, especially given the postponement of primary elections in some states due to the pandemic. For Tess Kerins, an organizer with the Nikil Saval for Pennsylvania State Senate campaign, the implications of the changes are more uncertain: “The coronavirus affects our abilities as a campaign but I’m not sure if it hinders us or helps us.” Saval launched his campaign to unseat Democratic incumbent Larry Farnese in the state’s urban 1st Senatorial district in December. His campaign champions progressive values and has already claimed big endorsements from the Philadelphia chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America, the Sunrise Movement, and Reclaim Philadelphia, an organizing group born out of the 2016 Sanders presidential campaign. “A lot of times grassroots campaigns win because they knock on doors so it’s frustrating that we can’t do that. But having an extra month means we get to talk to more people. I am optimistic, but I’m not sure how to tell in something like this.” One thing that has definitively changed in the case of the Saval campaign is how volunteers interact with voters when they do answer the phone.