Hunter 310 - Practical Sailor Print Edition Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latitude 38 December 2009

DecCoverTemplate 11/20/09 10:47 AM Page 1 Latitude 38 VOLUME 390 December 2009 WE GO WHERE THE WIND BLOWS DECEMBER 2009 VOLUME 390 Warm Holiday Wishes from the Crew at Grand Marina • Prime deep water concrete slips in a variety of sizes DIRECTORY of • Great Estuary location at the heart GRAND MARINA of the beautiful Alameda Island TENANTS • Complete bathroom and shower Bay Island Yachts ......................... 10 facility, heated and tiled Blue Pelican Marine ................... 160 • FREE pump out station open 24/7 The Boat Yard at Grand Marina ... 19 • Full Service Marine Center and Lee Sails ....................................... 64 haul out facility Pacific Crest Canvas ..................... 55 Pacific Yacht Imports ..................... 9 • Free parking Rooster Sails ................................ 66 510-865-1200 Leasing Office Open Daily • Free WiFi on site! UK-Halsey Sailmakers ............... 115 2099 Grand Street, Alameda, CA 94501 And much more… www.grandmarina.com Page 2 • Latitude 38 • December, 2009 ★ Happy Holidays from all of us Sails: a Very at Pineapple Sails. We’ll be closed from Sat., Dec. 19, through Important Part! Sun., Jan. 3. Every boat has a story. But some boats’ stories are longer than others. VIP is one such boat. Designed and built by the Stephens Brothers of Stockton, VIP is number 7 of 19 Farallon Clippers, built between 1940 and 1962. The yard built her shortly after WWII as a gift to one of the Stephens Brothers, Theo, the Very Important Person. Some 55 years later Don Taylor, visiting friends for dinner, is sharing their coffee table book of all the beautiful wooden boats built by the Stephens boats when he found himself constantly flipping back to a photo of the 38’ Farallon Clipper. -

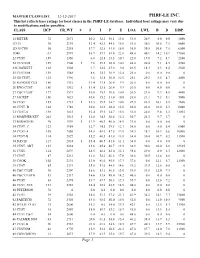

PHRF-LE INC. This List Reflects Base Ratings for Boat Classes in the PHRF-LE Database

MASTER CLASS LIST 12-12-2017 PHRF-LE INC. This list reflects base ratings for boat classes in the PHRF-LE database. Individual boat ratings may vary due to modifications and/or penalties. CLASS HCP CR_WT # J I P E LOA LWL B D DISP. 11 METER 72 2071 10.2 32.2 36.1 13.6 33.0 26.9 8.0 0.0 3600 1D 35 30 2195 12.4 42.5 44.5 18.0 35.0 30.5 10.8 7.5 6600 1D 35 CUS 30 2248 17.7 42.5 44.5 18.0 35.0 30.5 10.8 7.5 6600 1D48 -33 2939 16.7 57.7 61.4 22.0 48.0 40.1 14.2 10.1 17860 22 CUST 189 1356 6.8 22.8 24.5 10.7 22.0 19.0 7.2 4.9 2100 24 CUSTOM 159 1500 1 9.8 29.5 28.0 10.0 24.0 20.4 9.1 4.5 2900 245 JACKETT 168 1503 9.7 32.0 27.4 9.8 24.5 18.4 8.3 4.2 3300 25 CUSTOM 159 1548 8.6 32.3 30.9 12.4 25.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0 25 GS CUST. 135 1596 9.6 33.8 30.0 12.0 25.1 20.3 8.5 4.7 4000 26 RANGER CUS 186 1532 11.4 33.5 26.4 9.9 26.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0 26 RNG.CUST 186 1532 1 11.4 33.5 26.4 9.9 26.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0 27 C&C CUST 177 1571 10.0 35.3 30.6 10.8 26.5 23.0 9.3 4.8 4400 27 JACKET 156 1623 10.6 35.2 31.0 10.8 26.8 21.1 9.3 5.1 5000 30 CUST 153 1733 1 12.5 39.5 34.7 10.6 29.3 23.5 10.1 5.5 7600 30 CUST. -

MORE DETAILS 1999 Hunter

MORE DETAILS 1999 Hunter 310 Looking for a great mid-size cruiser? The Hunter 310 perfect sailboat for the Coastal, Interbanks and beyond? S/V TINKERBELLE is Extra clean, well equipped, and has been lovingly used and maintained. Having both a roller furling main and jib makes reefing a breeze in any type of winds. The 10'10" beam and 30' 10" LOA makes for exceptional stability and performance. Traveler mounted on a fiberglass arch - keeps lines out of the way and protects passengers from bumps to the head. Full instrumentation package includes speed, wind and depth. The Spacious bright interior boasts 6' 4" headroom and two separate fully enclosed staterooms for privacy. With great natural light throughout the cabins, multiple hatches, and screened ports. The air conditioned salon can handle entertaining or dining with friends and family. There is an immense rounded cockpit that allows the crew to participate or just relax. She has a walk thru transom with swim platform and fold down ladder. S/V TINKERBELLE is truly a great cruiser. Mini Pictures Boat Details Class Sails Category Sloop, Racers and Cruisers, Cruisers Year 1999 (by Serial#); 1998 (Documentation) Make Hunter Length 31' Propulsion Type Single Inboard Hull Material Fiberglass Fuel Type Diesel Location Southport, NC MORE DETAILS Accommodations This mid-size cruiser provides two private staterooms with privacy provided by bulkheads rather than curtains. The large dinette converts to a double berth with the settees having plenty of storage. In addition, the main cabin has 6'4" headroom. For a 31 footer, this cruiser offers a great deal of room. -

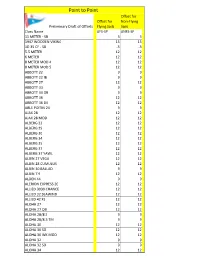

Copy of P2P Ratings for Release Dr Mod.Xlsx

Point to Point Offset for Offset for Non-Flying Preliminary Draft of Offsets Flying Sails Sails Class Name ΔFS-SP ΔNFS-SP 11 METER - SB 3 3 1947 WOODEN VIKING 15 15 1D 35 CF - SB -3 -3 5.5 METER 12 12 6 METER 12 12 8 METER MOD 4 12 12 8 METER MOD 5 12 12 ABBOTT 22 9 9 ABBOTT 22 IB 9 9 ABBOTT 27 12 12 ABBOTT 33 9 9 ABBOTT 33 OB 9 9 ABBOTT 36 12 12 ABBOTT 36 DK 12 12 ABLE POITIN 24 9 9 AJAX 28 12 12 AJAX 28 MOD 12 12 ALBERG 22 12 12 ALBERG 29 12 12 ALBERG 30 12 12 ALBERG 34 12 12 ALBERG 35 12 12 ALBERG 37 12 12 ALBERG 37 YAWL 12 12 ALBIN 27 VEGA 12 12 ALBIN 28 CUMULUS 12 12 ALBIN 30 BALLAD 9 9 ALBIN 7.9 12 12 ALDEN 44 9 9 ALERION EXPRESS 20 12 12 ALLIED 3030 CHANCE 12 12 ALLIED 32 SEAWIND 12 12 ALLIED 42 XL 12 12 ALOHA 27 12 12 ALOHA 27 OB 12 12 ALOHA 28/8.5 9 9 ALOHA 28/8.5 TM 9 9 ALOHA 30 12 12 ALOHA 30 SD 12 12 ALOHA 30 WK MOD 12 12 ALOHA 32 9 9 ALOHA 32 SD 9 9 ALOHA 34 12 12 Point to Point Offset for Offset for Non-Flying Preliminary Draft of Offsets Flying Sails Sails Class Name ΔFS-SP ΔNFS-SP ALOHA 8.2 12 12 ALOHA 8.2 OB 12 12 AMF 2100 12 12 ANCOM 23 12 12 ANDREWS 30 CUS 1 L30 9 9 ANDREWS 30 CUS 2 L30 9 9 ANDREWS 30 CUS 3 L30 9 9 ANDREWS 30 CUS 4 L30 9 9 ANDREWS 30 CUS 5 L30 9 9 ANDREWS 30 CUS 6 L30 9 9 ANDREWS 30 CUS 7 L30 9 9 ANTRIM 27 IB - SB -9 -9 ANTRIM 27 OB - SB -9 -9 APHRODITE 101 9 9 AQUARIUS 23 9 9 ARCHAMBAULT 31 6 6 ARCHAMBAULT 35 CF 3 3 ARCHAMBAULT 40RC CF MOD 3 3 ATLANTIC 12 12 AURORA 40 KCB 9 9 AVANCE 36 12 12 B 25 -SB 3 3 B 32 OB MOD -SB -3 -3 BALATON 31 12 12 BALBOA 26 SK 9 9 BALTIC 42 C&C 9 9 BALTIC 42 DP 9 9 BANNER -

Hunter Sailing Yacht Sales

This is a monthly sold boat report. If you would like an Massey Yacht expanded report please contact, Ed Massey at [email protected] Sales & Service or 941-725-2350 Hunter Sold Boat Report for Jun 2020 Listed Date Sold Mos to % of Year US$ Listed US$ Sold Date State Sell Listed$ 50' Hunter 50 2011 285,000 Oct-19 260,000 Jun-20 CT 9 91% 46' Hunter 460 2002 126,000 Mar-20 108,000 Jun-20 VA 4 86% 46' Hunter 460 2001 129,900 Aug-17 103,500 Jun-20 VA 35 80% 46' Hunter 460 2000 145,000 Feb-20 135,000 Jun-20 FL 5 93% 45' Hunter 45 Deck Salon 2008 179,900 Jun-19 169,500 Jun-20 MD 13 94% 45' Hunter Passage 450 1997 100,000 Mar-19 50,000 Jun-20 SC 16 50% 44' Hunter 44 AC 2005 128,700 Nov-19 122,000 Jun-20 MD 8 95% 42' Hunter Passage 42 1991 84,900 Jul-19 73,000 Jun-20 CA 12 86% 42' Hunter Passage 420 2001 115,000 May-20 105,000 Jun-20 CA 2 91% 42' Hunter Passage 420 2000 95,000 Mar-20 94,000 Jun-20 CA 4 99% 42' Hunter Passage 420 1999 94,900 Apr-20 90,500 Jun-20 CA 3 95% 41' Hunter 40.5 Legend 1996 74,500 Feb-20 63,000 Jun-20 MA 5 85% 41' Hunter 41 Deck Salon 2007 149,950 Nov-19 137,000 Jun-20 WA 8 91% 41' Hunter 41 Deck Salon 2007 135,500 Jan-18 120,000 Jun-20 TX 30 89% 41' Hunter 41. -

First Coast Offshore Challenge, 2006

First Coast Offshore Challenge, 2006 April 19 - 22 RRS A4.2 (no throw-out) Final Overall Regatta Series Div Yacht Name Skipper Club Sail # Yacht Make PHRF Race 1 Race 2 Race 3 Sum Place S Renegade Tom Slade EFYC 52422 Santa Cruz 52 -6 4 1 1 6 1 S Talisman Hal Neill EFYC 74 Express 27 135 3 2 3 8 2 S Whisper Tom Bell NFCC 41038 C&C 38 117 1 4 4 9 3 S Cracker Jack Hal Runnfeldt RC 1411 Morgan 27 165 2 5 2 9 4 S Boom Brent Fulton NFCC 4 Ultimate 24 102 5 3 6 14 5 S Ocean Avenue Hunt Bowman SAYC H356 Hunter 356 147 7 6 5 18 6 S Skimmer Graeme Nichol AISC J30 J 30 141 6 7 7 20 7 S Someday Larry Jones SAYC 683 Evelyn 32-2 93 8 9 8 25 8 entered in series: 8 Non-Spinnaker N The Last Mangas Robert Ford HRYC 711 Beneteau 36 114 1 1 5 7 1 N Blue Sky Dana Hunter SAYC 174 C&C 32 165 6 2 1 9 2 N Changing Channels Rick Elbracht NFCC H35.5 Hunter Legend 35 153 4 3 3 10 3 N Sunday Mornin' Jazz Gene Sokolowski AISC 590 Islander 36 165 3 6 2 11 4 N Bananas Bob McClemens NFCC 306 Beneteau 1st 38 120 2 6 4 12 5 entered in series: 5 Cruiser B Jolie Dancer Richard Klimas NFCC 52365 Irwin 43 Mk III 168 1 Abandoned 121 A Osprey Tom Holland NFCC Morgan 38 156 3 Abandoned 252 A Bernoulli Allen Jones NFCC 67 Pearson 36 150 2 Abandoned 573 B Caper Peter Korous NFCC 81 Pearson 35 195 8 Abandoned 3114 B Koinonia Don Gilbert NFCC 781 Hunter 33 186 7 Abandoned 4115 A B&B Bill Pierce NFCC 798 Hunter 38 159 5 Abandoned 6116 A Monkey's Uncle Carter Quillen NFCC 110 Hunter 45 CC 126 6 Abandoned 8147 B Continuation Alec Boriss NFCC Irwin 34 Citation 177 4 Abandoned 14 18 8 -

UNITED STATES PERFORMANCE HANDICAP RACING FLEET LOW, HIGH, AVERAGE and MEDIAN PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS for the Years 2005 Through 2011 IMPORTANT NOTE

UNITED STATES PERFORMANCE HANDICAP RACING FLEET LOW, HIGH, AVERAGE AND MEDIAN PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS for the years 2005 through 2011 IMPORTANT NOTE The following pages lists base performance handicaps (BHCPs) and low, high, average, and median performance handicaps reported by US PHRF Fleets for well over 4100 boat classes or types displayed in Adobe Acrobat portable document file format. Use Adobe Acrobat’s ‘FIND” feature, <CTRL-F>, to display specific information in this list for each class. Class names conform to US PHRF designations. The information for this list was culled from data sources used to prepare the “History of US PHRF Affiliated Fleet Handicaps for 2011”. This reference book, published annually by the UNITED STATES SAILING ASSOCIATION, is often referred to as the “Red, White, & Blue book of PHRF Handicaps”. The publication lists base handicaps in seconds per mile by Class, number of actively handicapped boats by Fleet, date of last reported entry and other useful information collected over the years from more than 60 reporting PHRF Fleets throughout North America. The reference is divided into three sections, Introduction, Monohull Base Handicaps, and Multihull Base Handicaps. Assumptions underlying determination of PHRF Base Handicaps are explicitly listed in the Introduction section. The reference is available on-line to US SAILING member PHRF fleets and the US SAILING general membership. A current membership ID and password are required to login and obtain access at: http://offshore.ussailing.org/PHRF/2011_PHRF_Handicaps_Book.htm . Precautions: Reported handicaps base handicaps are for production boats only. One-off custom designs are not included. A base handicap does not include fleet adjustments for variances in the sail plan and other modifications to designed hull form and rig that determine the actual handicap used to score a race. -

High-Low-Mean PHRF Handicaps

UNITED STATES PERFORMANCE HANDICAP RACING FLEET HIGH, LOW, AND AVERAGE PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS IMPORTANT NOTE The following pages list low, high and average performance handicaps reported by USPHRF Fleets for over 4100 boat classes/types. Using Adobe Acrobat’s ‘FIND” feature, <CTRL-F>, information can be displayed for each boat class upon request. Class names conform to USPHRF designations. The source information for this listing also provides data for the annual PHRF HANDICAP listings (The Red, White, & Blue Book) published by the UNITED STATES SAILING ASSOCIATION. This publication also lists handicaps by Class/Type, Fleet, Confidence Codes, and other useful information. Precautions: Handicap data represents base handicaps. Some reported handicaps represent determinations based upon statute rather than nautical miles. Some of the reported handicaps are based upon only one handicapped boat. The listing covers reports from affiliated fleets to USPHRF for the period March 1995 to June 2008. This listing is updated several times each year. HIGH, LOW, AND AVERAGE PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS ORGANIZED BY CLASS/TYPE Lowest Highest Average Class\Type Handicap Handicap Handicap 10 METER 60 60 60 11 METER 69 108 87 11 METER ODR 72 78 72 1D 35 27 45 33 1D48 -42 -24 -30 22 SQ METER 141 141 141 30 SQ METER 135 147 138 5.5 METER 156 180 165 6 METER 120 158 144 6 METER MODERN 108 108 108 6.5 M SERIES 108 108 108 6.5M 76 81 78 75 METER 39 39 39 8 METER 114 114 114 8 METER (PRE WW2) 111 111 111 8 METER MODERN 72 72 72 ABBOTT 22 228 252 231 ABBOTT 22 IB 234 252 -

LNKC PHRF RATINGS June 21, 2007

LNKC PHRF RATINGS June 21, 2007 Certificate Name Boat Name Sail # Boat Type HS% Spinnaker Base rating Race Rating 144 Miller Ledbetter Unvanquished 45954 Abbott 36 150% No 111 111 166 Jerry Huray Touch of Gray 1282 Albin Ballad 30 150% No 201 204 236 William North Pretty Baby 424 Beneteau 235 155% Yes 186 186 237 Mabry Tom Sovereign 0 Beneteau 235 WK 155% Yes 192 192 249 Kevin Meechan LOKAHI 306 Beneteau 235 WK OS 155% Yes 192 186 109 Charles Graham Blanc Bleau 133 Beneteau 285 FP RFA 175% Yes 183 183 148 Pete Rounds Watermark 279 Beneteau 35 147% Yes 132 132 160 Clement Caddell Tethys 55 Beneteau Oceanis 311 FP RFA 116% No 153 159 180 Michael & Hope Byles For Sale 215 Beneteau Oceanis 321 SD RFA 155% No 180 183 136 Bill Tavui Samoan Splash 98 Beneteau Oceanis 350 WK RFA 155% Yes 168 171 116 Mary Lynn Strange Hucklebuck 18 Buccaneer 295 152% Yes 183 183 139 Steve Lefler Quest 78 C&C 110 WK FP RFA 135% No 87 93 218 Jeff Stallings Cayenne 20067 C&C 30 SD FP 150% Yes 180 183 190 Dave Powell Poppy 751 Cal 22 RFA 150% No 249 252 221 Hans Lassen Prime Time 474 Capri 22 Catalina WK 149% Yes 210 210 119 Mike Cooney Crusader 443 Capri 25 Catalina 150% Yes 174 174 168 Andrew Howell Check Six 427 Capri 25 Catalina 150% Yes 174 174 246 Ray Palmer Windbreaker 0 Capri 26 Catalina IB 150% No 213 213 172 Dana Castro Wanderer 53200 Capri 30 Catalina 155% Yes 114 114 198 Rick Jarrett Tuff Life Too 13865 Catalina 22 SK 146% No 279 279 154 Gene Wood Wooden Boat 14650 Catalina 22 WK 155% No 279 279 155 Doug Riley Life o' Riley 5231 Catalina 25 FK TM 154% Yes 228 228 104 Diane Merryman 0 5957 Catalina 25 WK TM 150% No 234 234 145 Dominique Falewee Chessie Cat 5766 Catalina 27 IB FP RFA 150% No 216 222 167 Ellen Moretz Tintinnabulator 645 Catalina 27 TM IB FP 100% No 204 207 114 John Davis Flyin Free 6044 Catalina 27 TM IB FP RFA 155% No 204 210 213 Neil Liner Air Transit 5711 Catalina 27 TM OB 153% Yes 201 201 122 Matt Zaremski Overboard 5554 Catalina 30 TM WK FP RFA 148% Yes 169 175 203 Dr. -

Massey Yacht Sales Hunter Sold Boat Report for May 2019

This is a monthly sold boat report. If you would like an expanded report please contact, Ed Massey at [email protected] or 941-725-2350 Massey Yacht Sales Hunter Sold Boat Report for May 2019 Date % of Year Listed US$ Listed Sold US$ Sold Date Location Mos to Sell Listed$ 46' Hunter 466 2004 174,500 Mar-18 161,750 May-19 NC, USA 15 93% 46' Hunter 466 2002 155,000 Mar-19 138,000 May-19 MD, USA 3 89% 46' Hunter 466 LE 2006 159,000 Mar-19 150,000 May-19 FL, USA 3 94% 46' Hunter Passage 456 2005 179,500 Mar-19 169,500 May-19 CA, USA 3 94% 45' Hunter 45 Deck Salon 2010 189,900 Jul-16 185,000 May-19 MI, USA 35 97% 45' Hunter 45 LEGEND 1987 59,500 Oct-18 55,000 May-19 MA, USA 8 92% 45' Hunter 45cc 2006 189,900 Dec-18 156,000 May-19 WA, USA 6 82% 41' Hunter 40.5 1997 79,500 Sep-18 65,000 May-19 CA, USA 9 82% 41' Hunter 410 2003 86,900 Nov-18 72,500 May-19 FL, USA 7 83% 41' Hunter 410 2002 99,900 Feb-19 90,000 May-19 MD, USA 4 90% 41' Hunter 410 1998 104,900 Dec-18 98,000 May-19 WA, USA 6 93% 40' Hunter 40 1985 42,500 Oct-18 42,000 May-19 MD, USA 8 99% 40' Hunter 40.5 1996 79,900 Oct-18 62,300 May-19 CA, USA 8 78% 40' Hunter 40.5 Wing Keel 1995 79,900 Jan-19 76,000 May-19 FL, USA 5 95% 38' Hunter 386 2003 85,000 Dec-17 75,000 May-19 NY, USA 18 88% 37' Hunter 37 1987 39,800 Aug-18 37,500 May-19 OH, USA 10 94% 37' Hunter 37' Cherubini Cutter 1979 12,000 Apr-17 12,000 May-19 KY, USA 26 100% 37' Hunter 376 1997 65,000 Mar-19 65,000 May-19 CT, USA 3 100% 37' Hunter 376 1997 62,900 Apr-19 58,000 May-19 CA, USA 2 92% 37' Hunter 376 1996 44,900 -

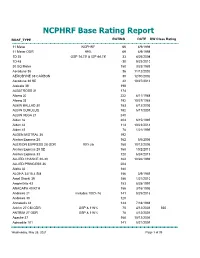

NCPHRF Base Rating Report

NCPHRF Base Rating Report BOAT_TYPE RATING DATE DW Class Rating 11 Meter NCPHRF 66 4/9/1998 11 Meter ODR 99% 69 4/9/1998 1D 35 OSP 14.75' & ISP 44.78' 33 4/26/2004 1D 48 -30 9/23/2010 30 SQ Meter 150 3/23/1989 Aerodyne 38 36 11/12/2002 AERODYNE 38 CARBON 30 12/30/2002 Aerodyne 38 SD 42 10/27/2016 Alajuela 38 198 ALBATROSS 31 174 Alberg 30 222 8/11/1988 Alberg 35 192 10/27/1988 ALBIN BALLAD 30 183 8/12/2003 ALBIN CUMULUS 192 5/17/2001 ALBIN VEGA 27 240 Alden 32 204 6/15/1995 Alden 44 114 10/23/2014 Alden 45 78 1/21/1999 ALDEN MISTRAL 36 192 Alerion Express 28 162 5/6/2006 ALERION EXPRESS 28 ODR 90% jib 168 10/12/2006 Alerion Express 28 SD 168 10/2/2013 Alerion Express 33 120 6/24/2019 ALLIED CHANCE 30-30 162 10/26/1994 ALLIED PRINCESS 36 204 Aloha 32 180 ALOHA 34/10.4 SM 156 3/9/1989 Amel Sharki 39 186 1/21/2010 Amphritrite 43 153 8/28/1991 ANACAPA 40 KTH 156 3/16/1995 Andrews 21 includes 100% hs 141 8/25/2016 Andrews 30 120 Annapolis 44 144 7/18/1988 Antrim 27 CM ODR OSP & 116% 75 4/12/2001 555 ANTRIM 27 ODR OSP & 116% 78 4/12/2001 Apache 37 168 10/12/2006 Aphrodite 101 141 5/21/2009 Wednesday, May 26, 2021 Page 1 of 39 BOAT_TYPE RATING DATE DW Class Rating Aquarius 21 288 1/21/2019 Archambault 27 w/ 12.2' spl & 105% hs 78 4/23/2015 Aries 31 258 Aries 32 234 6/29/1989 Atkin 38 183 4/8/1999 Azzura 310 57 12/7/1995 B 30 ludes square-top main & small 78 3/29/2021 B-25 141 7/1/1999 B-25 ODR 135 7/1/1999 Baba 30 240 Baba 35 SM 192 3/12/1998 Baba 40 144 2/16/1989 Baba 40 TM 138 6/18/1992 Bahama 25 252 Balboa 26 FK 222 Balboa 26 SK 228 BALBOA -

US Sailing Rig Dimensions Database

ABOUT THIS CRITICAL DIMENSION DATA FILE There are databases that record critical dimensions of production sailboats that handicappers may use to identify yachts that race and to help them determine a sailing number to score competitive events. These databases are associated with empirical or performance handicapping systems worldwide and are generally available from those organizations via internet access. This data file contains dimensions for some, but not all, production boats reported to USPHRF since 1995. These data may be used to support performance handicapping by affiliated USPHRF fleets. There are many more boats in databases that sailmakers and handicappers possess. The USPHRF Technical Subcommittee and the US SAILING Offshore Office have several. This Adobe Acrobat file contains data mostly supplied by USPHRF affiliated fleets, a few manufacturers, naval architects, and others making contributions to database. While this data file is generally helpful, it does contain errors of omission and inaccuracies that are left to users to rectify by sending corrections to USPHRF by way of the data form below. The form also asks for additional information that anticipates the annual fall data collection from USPHRF affiliated fleets. Return this form to the USPHRF Committee c/o US SAILING. How do you access information in this data file of well over 5000 records for a specific boat? Use Adobe Acrobat Reader’s ‘FIND” feature, <CTRL-F>. Information currently in the file will be displayed for each Yacht Type/Class upon request. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________