Journal of English Studies, Vol 17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" Vinyl Single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE in the MOVIES Dr

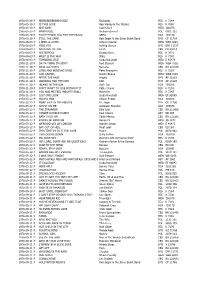

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" vinyl single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE IN THE MOVIES Dr. Hook EMI 7" vinyl single CP 11706 1978-05-22 P COUNT ON ME Jefferson Starship RCA 7" vinyl single 103070 1978-05-22 P THE STRANGER Billy Joel CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222406 1978-05-22 P YANKEE DOODLE DANDY Paul Jabara AST 7" vinyl single NB 005 1978-05-22 P BABY HOLD ON Eddie Money CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222383 1978-05-22 P RIVERS OF BABYLON Boney M WEA 7" vinyl single 45-1872 1978-05-22 P WEREWOLVES OF LONDON Warren Zevon WEA 7" vinyl single E 45472 1978-05-22 P BAT OUT OF HELL Meat Loaf CBS 7" vinyl single ES 280 1978-05-22 P THIS TIME I'M IN IT FOR LOVE Player POL 7" vinyl single 6078 902 1978-05-22 P TWO DOORS DOWN Dolly Parton RCA 7" vinyl single 103100 1978-05-22 P MR. BLUE SKY Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) FES 7" vinyl single K 7039 1978-05-22 P HEY LORD, DON'T ASK ME QUESTIONS Graham Parker & the Rumour POL 7" vinyl single 6059 199 1978-05-22 P DUST IN THE WIND Kansas CBS 7" vinyl single ES 278 1978-05-22 P SORRY, I'M A LADY Baccara RCA 7" vinyl single 102991 1978-05-22 P WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH Jon English POL 7" vinyl single 2079 121 1978-05-22 P I WAS ONLY JOKING Rod Stewart WEA 7" vinyl single WB 6865 1978-05-22 P MATCHSTALK MEN AND MATCHTALK CATS AND DOGS Brian and Michael AST 7" vinyl single AP 1961 1978-05-22 P IT'S SO EASY Linda Ronstadt WEA 7" vinyl single EF 90042 1978-05-22 P HERE AM I Bonnie Tyler RCA 7" vinyl single 1031126 1978-05-22 P IMAGINATION Marcia Hines POL 7" vinyl single MS 513 1978-05-29 P BBBBBBBBBBBBBOOGIE -

Pershing's Right Hand

PERSHING’S RIGHT HAND: GENERAL JAMES G. HARBORD AND THE AMERICAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCES IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR A Dissertation by BRIAN FISHER NEUMANN Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2006 Major Subject: History PERSHING’S RIGHT HAND: GENERAL JAMES G. HARBORD AND THE AMERICAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCES IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR A Dissertation by BRIAN FISHER NEUMANN Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Arnold P. Krammer Committee Members, H.W. Brands Charles E. Brooks Peter J. Hugill Brian M. Linn Head of Department, Walter Buenger August 2006 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT Pershing’s Right Hand: General James G. Harbord and the American Expeditionary Forces in the First World War. (August 2006) Brian Fisher Neumann, B.A., University of Southern California; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Arnold P. Krammer This project is both a wartime biography and an examination of the American effort in France during the First World War. At its core, the narrative follows the military career of Major General James G. Harbord. His time in France saw Harbord serve in the three main areas of the American Expeditionary Forces: administration, combat, and logistics. As chief of staff to AEF commander General John J. Pershing, Harbord was at the center of the formation of the AEF and the development of its administrative policies. -

2Pac Greatest Hits 01 Keep Ya Head up 02 2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted

Downloaded from: justpaste.it/yp43 2Pac Greatest Hits 01 Keep ya head up 02 2 Of amerikaz most wanted 03 Temptations 04 God bless the dead 05 Hail Mary 06 Me against the world 07 How do u want it 08 So many tears 09 Unconditional love 10 Trapped 11 Life goes on 12 Hit 'em up 13 Troublesome 96' 14 Brenda's got a baby 15 I ain't mad at cha 16 I get around 17 Changes 18 California love (original version) 19 Picture me rollin' 20 How long will they mourn me 21 Toss it up 22 Dear mama 23 All about you 24 To live & die in L.A. 25 Heartz of men A Teens Greatest Hits (2004) 01 Mamma Mia 02 Upside down 03 Gimme gimme gimme 04 Floorfiller 05 Dancing queen 06 A perfect match 07 To the music 08 Halfway around the world 09 Sugar rush 10 Super trouper 11 Heartbreak lullaby 12 Can't help falling in love 13 Let your heart do all the talking 14 The final cut 15 With or without you 16 I promised myself A Teens Greatest Hits Back A Teens Greatest Hits CD A Teens Greatest Hits A ha Greatest Hits (Ltd.Ed (2CD) 2009 101 a ha foot of the mountain atrium 102 a ha celice atrium 103 a ha summer moved on atrium 104 a ha lifelines atrium 105 a ha the bandstand atrium 106 a ha dont do me any favours atrium 107 a ha minor earth major sky atrium 108 a ha analogue atrium 109 a ha velvet atrium 110 a ha mother nature goes to heaven atrium 111 a ha the sun never shone that day atrium 112 a ha forever not yours atrium 113 a ha you wanted more atrium 114 a ha cosy prisons atrium 115 a ha shadowside atrium 116 a ha thought that it was you atrium 117 a ha little black heart -

Monkey Grip Music Creditsx

incidental music composed and conducted by Bruce Smeaton 'Gonna Get You' 'Girlfriends' 'Boys in Town' 'Only You' 'Only Lonely' 'Elsie' Performed by Divinyls Christina Amphlett Jeremy Paul Mark McEntee Bjarne Ohlin Richard Harvey Divinyls songs composed by McEntee & Amphlett Divinyls appear courtesy of WEA Records Pty Ltd Music produced by Mark Opitz Released by WEA Records Pty Ltd Australia 'Ghosts of Love' Don Miller-Robinson Theme Music - Pianist Stephen McIntyre Theatre Excerpt Phil Motherwell 'Sweet' 'Keep It Up' 'Flexible' Jo Jo Zep & The Falcons 'Fall Guy' Paul Kelly & The Dots 'Twist Senorita' Sports Mushroom Records 'Brick Wall' Euan Thorburn Mouth Records Allan Eaton Studios Pty Ltd Composer Bruce Smeaton provided the incidental music, and also the theme music, featuring Stephen McIntyre on piano, which runs over head and tail credits. Smeaton was particularly active in the late 1970s and early 1980s, after the indignity of having his score dumped from The Earthling, which said more about the film than Smeaton's work. Smeaton moved into high end TV miniseries (The Timeless Land in 1980, A Town Like Alice in 1981, and the WWI show 1915 in 1982), while still working with Fred Schepisi (the western Barbarosa in 1982), and doing some Australian feature film oddities, such as … Maybe This Time, Grendel Grendel Grendel and Squizzy Taylor. Smeaton had started out by composing two of the segment scores (The Husband and The Priest) for the portmanteau feature film Libido, before doing the score for Peter Weir's The Cars That Ate Paris, and then moving on to do David Baker's The Great Macarthy. -

Ketabton.Com (C) Ketabton.Com: the Digital Library (C) Ketabton.Com: the Digital Library

Ketabton.com (c) ketabton.com: The Digital Library (c) ketabton.com: The Digital Library DEDICATION TO THE MEMORY OF ROLF FASTE AND BILL MOGGRIDGE (c) ketabton.com: The Digital Library CONTENTS Dedication Introduction: Yellow-Eyed Cats 1 Nothing Is What You Think It Is 2 Reasons Are Bullshit 3 Getting Unstuck 4 Finding Assistance 5 Doing Is Everything 6 Watch Your Language 7 Group Habits 8 Self-Image by Design 9 The Big Picture 10 Make Achievement Your Habit Acknowledgments Notes Bibliography About the Author Credits Copyright About the Publisher (c) ketabton.com: The Digital Library INTRODUCTION: YELLOW-EYED CATS Paddy’s idea wasn’t the most daring in the class. When you first met him, you could tell he came from a military background. It was evident in his stance—stoic and somewhat intimidating. He went to boarding school in Northern Ireland from age seven to eighteen and then joined the Royal Marines, where he served for ten years. Civilian life scared him, and after leaving the military, he quickly sought out the safety net of a job within a large corporation and a regimented schedule. A journalist, he moved around the world quite a bit, finding work at places like the BBC and CNBC. “I’m something of a company man,” he would later tell me. When I met him he was at Stanford University on a one-year fellowship for midcareer journalists. He was taking a class of mine, “The Designer in Society,” which encourages students to examine and take control of their lives. I’ve been a professor of engineering at Stanford for fifty-two years, and along the way I’ve met too many engineers who once dreamed of starting a company of their own— and instead ended up working for large Silicon Valley companies and never taking that big step toward making their dreams a reality. -

Close Encounters

Close Encounters Essays on Russian Literature ars Rossica series Editor: David BETHEa (University of Wisconsin — Madison) Close Encounters Essays on Russian Literature Robert Louis JaCkson BOSTON /2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book as available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-936235-56-8 On the cover: “Come, let us build ourselves a city,” by Leslie Jackson. Cover design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com To Leslie Painter and Poet Companion of My Life Table of Contents Introduction Introductory Note By Horst-Jürgen Gerigk .............................................. -

1978-05-29 P Bbbbbbbbbbbbboogie

1978-05-29 P BBBBBBBBBBBBBOOGIE Skyhooks FES K 7144 1978-05-29 P IS THIS LOVE Bob Marley & the Wailers FES K 7080 1978-05-29 P KHE SANH Cold Chisel WEA 100073 1978-05-29 P WARM RIDE Graham Bonnet POL 6001 112 1978-05-29 P EAGLE/THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC ABBA RCA 103130 1978-05-29 P STILL THE SAME Bob Seger & the Silver Bullet Band EMI CP 11724 1978-06-03 P I NEED A LOVER Johnny Cougar WEA WEA 4091 1978-06-03 P MISS YOU Rolling Stones EMI EMI 11727 1978-06-03 P NOTHING TO HIDE Finch CBS PR 45014 1978-06-03 P YESTERFOOL Sinclair Bros. FES K 7071 1978-06-03 P WEST IS THE WAY Stars FES K 7143 1978-06-03 P TUMBLING DICE Linda Ronstadt WEA E 45479 1978-11-20 P DA YA THINK I'M SEXY? Rod Stewart WEA WBA 4102 1978-11-20 P WELL ALL RIGHT Santana CBS BA 222479 1978-11-20 P LONG AND WINDING ROAD Peter Frampton FES K 7219 1978-11-20 P GOD KNOWS Debby Boone WEA WBA 4100 1978-11-20 P AFTER THE RAIN Angels EMI AP 11823 1978-11-20 P WORKING FOR THE MAN BAD EMI AP 11826 1978-11-20 P ISLAND IN THE SUN Dark Tan RCA 103205 1978-11-20 P DON'T WANT TO LIVE WITHOUT IT Pablo Cruise FES K 7276 1978-11-20 P YOU MAE ME FEEL (MIGHTY REAL) Sylvester FES K 7247 1978-11-20 P JUST ONE LOOK Linda Ronstadt WEA EF 90099 1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE IN THE MOVIES Dr. -

Leonard Cohen the Modern Troubadour

PALACKÝ UNIVERSITY, OLOMOUC FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND AMERICAN STUDIES LEONARD COHEN THE MODERN TROUBADOUR DOCTORAL DISSERTATION Author: Mgr. Jiří Měsíc Supervisor: Prof. PhDr. Josef Jařab, CSc. 2016 UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA KATEDRA ANGLISTIKY A AMERIKANISTIKY LEONARD COHEN MODERNÍ TRUBADÚR DIZERTAČNÍ PRÁCE Autor práce: Mgr. Jiří Měsíc Vedoucí práce: Prof. PhDr. Josef Jařab, CSc. 2016 The research and publication of this work have been made possible thanks to the direct support of the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic for specific-purpose university research in the year 2015 at Palacký University Olomouc and thanks to the Institut français of Prague and the French Embassy in Prague which enabled the author to undertake two research stays at the University Paul-Valéry in Montpellier in 2014 and 2015. Zpracování této dizertační práce bylo umožněno díky účelové podpoře na specifický vysokoškolský výzkum udělené roku 2015 Univerzitě Palackého v Olomouci Ministerstvem školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy ČR a díky Francouzskému institutu a Francouzskému velvyslanectví v Praze, které autorovi umožnilo dva výzkumné pobyty na Univerzitě Paul-Valéry v Montpellier v letech 2014 a 2015. ABSTRACT This dissertation thesis arose from thinking about literary tradition as described by the Anglo-American modernists Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot. In their view, the tradition of European love-lyrics crystallised in the work of the medieval Occitan troubadours who were influenced by the cultural and political milieu of the contemporary Occitanie and whose work reflected the religious influences of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The main subject of their poetry was the worship of the divinised feminine character resembling the Christian Virgin Mary, Gnostic Sophia or the ancient Mother Goddess. -

Implications of Sexual Scripting for Pleasure and Violence Dissertation Present

“Was It Good For You?”/Is It Good For Us?: Implications of Sexual Scripting for Pleasure and Violence Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Emma Marie Carroll Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Korie Edwards, Advisor Steven Lopez Kristi Williams 1 Copyrighted by Emma Marie Carroll 2019 2 Abstract Quantitative research on sexuality suggests that sexual satisfaction is important for physical health, mental health, and relationship outcomes, but most of this research fails to capture the subjective ways that sexual satisfaction is perceived and achieved. In this study I employ in-depth qualitative interviews to explore the ways that women and men understand both “good” and “bad” sex. I employ sexual script theory as a framework to explain the ways that sexual expectations and behaviors are patterned in reference to cultural, interpersonal, and intrapsychic understandings of sex. In the first chapter I explore the role of novelty as a factor in “good” sex and the tensions that exist between the predictable and the unfamiliar. In the second chapter I delve into the role that gender plays in constructing perceptions of sexual satisfaction and the ways that the narratives of men and women converge and differ. Finally, in the third chapter I address the prevalence of sexual violence reported by the women in my sample and explain how this is a product of the gendered norms embedded in cultural-level sexual scripts. Overall, my research suggests that women and men have similar expectations for what makes sex “good,” but dominant norms surrounding sexuality disproportionately place women in subordinate roles, and therefore greater risk of violence, during sex. -

Disposable Ties and the Urban Poor1

Disposable Ties and the Urban Poor1 Matthew Desmond Harvard University Sociologists long have observed that the urban poor rely on kinship networks to survive economic destitution. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork among evicted tenants in high-poverty neighborhoods, this article presents a new explanation for urban survival, one that emphasizes the importance of disposable ties formed between strang- ers. To meet their most pressing needs, evicted families often relied more on new acquaintances than on kin. Disposable ties facilitated the flow of various resources, but often bonds were brittle and fleet- ing. The strategy of forming, using, and burning disposable ties allowed families caught in desperate situations to make it from one day to the next, but it also bred instability and fostered misgivings among peers. How do the urban poor survive? When they obtain basic necessities, such as food and clothing, shelter and safety, how is it that they do so? And 1 I thank Mustafa Emirbayer for his tireless guidance and support. Javier Auyero, Jacob Avery, Felix Elwert, Herbert Gans, Colin Jerolmack, Shamus Khan, Michael McQuarrie, Alexandra Murphy, Adam Slez, Ruth Lo´pez Turley, Loı¨c Wacquant, Ed- ward Walker, Winnie Wong, and the AJS referees offered smart and substantive com- ments on previous drafts. I also am indebted to the people I met in Milwaukee, for their patience and hospitality, and to those who attended seminars at Brandeis, Co- lumbia, Harvard, the State University of New York at Buffalo, the University of Texas at Austin, and the 2010 American Sociological Association annual conference, where earlier versions of this article were presented.