The Paradox of Paradise Regained in the Left Behind Series A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Event of Global Vanishings – Please Read

In the Event of Global Vanishings – Please Read To: A Concerned Person who has no doubt been LEFT BEHIND. From: Pastor Rob Lee Re: Instructions on just what to do, and not do, right now. The fact that you are reading this tells me that you have experienced a traumatic event that has taken place. Millions of people all over the face of the earth have mysteriously disappeared. Millions of men, women, children, toddlers, infants, and even unborn babies are now gone. Although widespread panic has most likely accompanied this phenomenal event, there is an explanation. Please read the following. I am sure by now people are saying that it was UFO’s, aliens from another planet, or a change in the evolutionary process; a ‘selective elimination’ of sorts that caused the disappearances. Some may be saying that the global vanishings were caused by some kind of high-tech weapon that can vaporize people, and children are more susceptible to it. Perhaps there are many other crazy theories. The bottom-line fact is that Jesus Christ has returned for His Church just as He said He would. Just find a Bible and read the following passages: • 1 Thessalonians 4:16-17 – Referring to the “catching away” of the saints. • 1 Corinthians 15:51-54 – Referring to those who “shall not all sleep.” • John 11:25-26 – Referring to the Resurrection of Christ’s Church This is an event that has been prophesied in both the Old Testament and New Testament books of the Bible. Many pastors, teachers, scholars, and Christians have also believed in this global rapture event. -

978-1-4143-3501-8.Pdf

Tyndale House Novels by Jerry B. Jenkins Riven Midnight Clear (with Dallas Jenkins) Soon Silenced Shadowed The Last Operative The Brotherhood The Left Behind® series (with Tim LaHaye) Left Behind® Desecration Tribulation Force The Remnant Nicolae Armageddon Soul Harvest Glorious Appearing Apollyon The Rising Assassins The Regime The Indwelling The Rapture The Mark Kingdom Come Left Behind Collectors Edition Rapture’s Witness (books 1–3) Deceiver’s Game (books 4–6) Evil’s Edge (books 7–9) World’s End (books 10–12) For the latest information on Left Behind products, visit www.leftbehind.com. For the latest information on Tyndale fiction, visit www.tyndalefiction.com. 5*.-")":& +&33:#+&/,*/4 5:/%"-&)064&16#-*4)&34 */$ $"30-453&". *--*/0*4 Visit Tyndale’s exciting Web site at www.tyndale.com. Discover the latest about the Left Behind series at www.leftbehind.com. TYNDALE, Tyndale’s quill logo, and Left Behind are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. Glorious Appearing: The End of Days Copyright © 2004 by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins. All rights reserved. Cover photograph copyright © by Valentin Casarsa/iStockphoto. All rights reserved. Israel map © by Maps.com. All rights reserved. Author photo of Jerry B. Jenkins copyright © 2010 by Jim Whitmer Photography. All rights reserved. Author photo of Tim LaHaye copyright © 2004 by Brian MacDonald. All rights reserved. Left Behind series designed by Erik M. Peterson Published in association with the literary agency of Alive Communications, Inc., 7680 Goddard Street, Suite 200, Colorado Springs, CO 80920. www.alivecommunications.com. Scripture quotations are taken or adapted from the New King James Version.® Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. -

The Indwelling : the Beast Takes Possession / Tim Lahaye, Jerry B

Visit Tyndale’s exciting Web site at www.tyndale.com Discover the latest about the Left Behind series at www.leftbehind.com Copyright © 2000 by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins. All rights reserved. Cover photographs copyright © 1999 by Brian MacDonald. All rights reserved. Authors’ photo copyright © 1998 by Reg Francklyn. All rights reserved. Left Behind series designed by Catherine Bergstrom Cover photo illustration by Julie Chen Designed by Julie Chen Published in association with the literary agency of Alive Communications, Inc., 7680 Goddard Street, Suite 200, Colorado Springs, CO 80920. Scripture taken from the New King James Version. Copyright © 1979, 1980, 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Left Behind is a registered trademark of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data LaHaye, Tim F. The indwelling : the beast takes possession / Tim LaHaye, Jerry B. Jenkins. p. cm. ISBN 0-8423-2928-5 (hardcover) ISBN 0-8423-2929-3 (softcover) 1. Steele, Rayford (fictitious character)—Fiction. 2. Rapture (Christian eschatology)— Fiction. I. Jenkins, Jerry B. II. Title. PS3562.A315 I54 2000 813′.54—dc21 00-020562 Printed in the United States of America 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 7654321 ONE BUCK braced himself with his elbow crooked around a scaffolding pole. Thousands of panicked people fleeing the scene had, like him, started and involuntarily turned away from the deafening gunshot. It had come from per- haps a hundred feet to Buck’s right and was so loud he would not have been surprised if even those at the back of the throng of some two million had heard it plainly. -

Millennialism, Rapture and “Left Behind” Literature. Analysing a Major Cultural Phenomenon in Recent Times

start page: 163 Stellenbosch Theological Journal 2019, Vol 5, No 1, 163–190 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2019.v5n1.a09 Online ISSN 2413-9467 | Print ISSN 2413-9459 2019 © Pieter de Waal Neethling Trust Millennialism, rapture and “Left Behind” literature. Analysing a major cultural phenomenon in recent times De Villers, Pieter GR University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa [email protected] Abstract This article represents a research overview of the nature, historical roots, social contexts and growth of millennialism as a remarkable religious and cultural phenomenon in modern times. It firstly investigates the notions of eschatology, millennialism and rapture that characterize millennialism. It then analyses how and why millennialism that seems to have been a marginal phenomenon, became prominent in the United States through the evangelistic activities of Darby, initially an unknown pastor of a minuscule faith community from England and later a household name in the global religious discourse. It analyses how millennialism grew to play a key role in the religious, social and political discourse of the twentieth century. It finally analyses how Darby’s ideas are illuminated when they are placed within the context of modern England in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth century. In a conclusion some key challenges of the place and role of millennialism as a movement that reasserts itself continuously, are spelled out in the light of this history. Keywords Eschatology; millennialism; chiliasm; rapture; dispensationalism; J.N. Darby; Joseph Mede; Johann Heinrich Alsted; “Left Behind” literature. 1. Eschatology and millennialism Christianity is essentially an eschatological movement that proclaims the fulfilment of the divine promises in Hebrew Scriptures in the earthly ministry of Christ, but it also harbours the expectation of an ultimate fulfilment of Christ’s second coming with the new world of God that will replace the existing evil dispensation. -

Tim Lahaye 9 – Desecration

The Left Behind* series Left Behind Tribulation Force Nicolae Soul Harvest Apollyon Assassins The Indwelling The Mark Desecration Book 10-available summer 2002 ANTICHRIST TAKES THE THRONE DESECRATION #1: The Vanishings #2: Second Chance #3: Through the Flames #4: Facing the Future #5: Nicolae High #6: The Underground #7: Busted! #8: Death Strike #9: The Search Left Behind(r): The Kids #10: On the Run #11: Into the Storm #12: Earthquake! #13: The Showdown #14: Judgment Day #15: Battling the Commander #16: Fire from Heaven #17: Terror in the Stadium #18: Darkening Skies Special FORTY-TWO MONTHS INTO THE TRIBULATION; TWENTY-FIVE DAYS INTO THE GREAT TRIBULATION The Believers Rayford Steele, mid-forties; former 747 captain for Pan-Continental; lost wife and son in the Rapture; former pilot for Global Community Potentate Nicolae Carpathia; original member of the Tribulation Force; international fugitive; on assignment at Mizpe Ramon in the Negev Desert, center for Operation Eagle Cameron ("Buck") Williams, early thirties; former senior writer for Global Weekly; former publisher of Global Community Weekly for Carpathia; original member of the Trib Force; editor of cybermagazine The Truth; fugitive; incognito at the King David Hotel, Jerusalem Chloe Steele Williams, early twenties; former student, Stanford University; lost mother and brother in the Rapture; daughter of Rayford; wife of Buck; mother of fifteen-month-old Kenny Bruce; CEO of International Commodity Co-op, an underground network of believers; original Trib Force member; fugitive in exile, Strong Building, Chicago Tsion Ben-Judah, late forties; former rabbinical scholar and Israeli statesman; revealed belief in Jesus as the Messiah on international TV-wife and two teenagers subsequently murdered; escaped to U.S.; spiritual leader and teacher of the Trib Force; cyberaudience of more than a billion daily; fugitive in exile, Strong Building, Chicago Dr. -

Best Evidence We're in the Last Days

October 21, 2017 Best Evidence We’re In the Last Days Shawn Nelson Can we know when Jesus is coming back? Some people have tried to predict exactly when Jesus would come back. For example, Harold Camping predicted Sep. 6, 1994, May 21, 2011 and Oct. 21 2011. There have been many others.1 But the Bible says we cannot know exact time: Matthew 24:36 --- “But of that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, but My Father only.” Acts 1:7 --- “And He said to them, “It is not for you to know times or seasons which the Father has put in His own authority.” We might not know the exact time, but we can certainly see the stage is being set: Matthew 16:2-3 --- ‘He answered and said to them, “When it is evening you say, ‘It will be fair weather, for the sky is red’; and in the morning, ‘It will be foul weather today, for the sky is red and threatening.’ Hypocrites! [speaking to Pharisees about events of his 1st coming] You know how to discern the face of the sky, but you cannot discern the signs of the times.’ 1 Thessalonians 5:5-6 --- “5 But concerning the times and the seasons, brethren, you have no need that I should write to you. 2 For you yourselves know perfectly that the day of the Lord so comes as a thief in the night… 4 But you, brethren, are not in darkness, so that this Day should overtake you as a thief. -

Jesus Is Coming Back with His Saints

Series: The Glorious Appearing 3. Destroy the Saints (Rev 13:7a) (Rev 6:9-11) (Rev 7:13-17) Title: The Beasts (Dan 8:24) he shall destroy the mighty and the holy people. Text: (Revelation 13:1-18) (Dan 7:21, 25) made war with the saints, and prevailed (Dan 12:9-10) Many shall be purified, made white, tried; Jesus is Coming Back WITH His Saints They will be Beheaded! (Rev 20:4) (Heb 12:3-4) (Matt 24:36) But of that day and hour knoweth no man, (Matt 25:13) Watch therefore, 4. Dominate Society: (Rev 13:7b) (Dan 8:23, 25) 5. Delude Sinners: (Rev 13:8) The devil wants converts! I. The Beast From the Sea: (Vs 1-8) His Debut: (Vs 1) He has many names, or Aliases. (Vs 9-10) Warning to Tribulation Saints who read the bible. Beast Man of Sin, Mystery of Iniquity, Son of Perdition The Little Horn, The Antichrist. II. The Beast From the Earth: (Vs 11-18) This is The False Prophet: (Rev 16:13) (Rev 19:20; 20:10) “and saw a beast rise up out of the sea,” (Rev 17:15) “having seven heads” (Rev 17:9) 1. The Masquerade: (Vs 11-12) “10 horns, 10 crowns” (Rev 17:12) (Dan 7:24) Jesus warned us of this event: (Matt 24:24) He will exalt the Beast: (Rev 13:12) His Description: (Rev 13:2a) The Beast will be the son of Satan: (Gen 3:15) Seed of Satan 2. The Miracles: (Vs 13-15) The Stateliness of the Lion: Babylon The Purpose of the Miracles: (Rev 13:14; 16:14, 19:20) The Strength of the Bear: Medo-Persion But for the Lost…. -

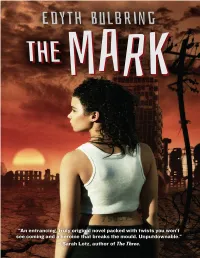

The Mark Edyth Bulbring

The Mark Edyth Bulbring Tafelberg For Charlotte, who loves stories PART ONE My name is Juliet Seven. The date is 264 PC. This year, I am going to wipe out my father and my sister. And then I will off myself. The Machine will record that I lived for fifteen years, worked as a drudge, and that my last address was Room 33, Section D, Slum City. Everything I do this year was spoken of before I existed. And it will be written in the blood of those who survive me. 1 The Monster A man flails in the breakers, thrashing the sea with windmill arms. “Monster!” he shouts. The Market Nags are the first to come screaming out of the shallows, breasts bouncing free from their underwear. “Mons ter, it’s a monster!” They swirl in circles on the beach, looking for a place to hide. The monster siren pierces the squeals of children being pulled from the breakers by beach wardens waving swimmers towards the dunes. “Get out of the water. Get out!” Their eyes scan the sea. Sun-worshippers jerk free of their torpor and abandon towels and bags. They stumble for the shelter of the dunes, dragging children along with them. “Run. Before the monster gets you. Run!” They urge toddlers along, slapping their blistered legs. The Market Nags gather their wits and clothes scattered on the beach, and follow them to safety. Glee swells my chest as I watch these fools. Buzzing around like flies trapped crazy behind a mesh screen. The sand trickles through my fingers as I wait for my moment. -

The Millennial Position of Spurgeon

TMSJ 7/2 (Fall 1996) 183-212 THE MILLENNIAL POSITION OF SPURGEON Dennis M. Swanson Seminary Librarian The notoriety of Charles Haddon Spurgeon has caused many since his time to claim him as a supporter of their individual views regarding the millennium. Spurgeon and his contemporaries were familiar with the four current millennial views—amillennialism, postmillennialism, historic premillennialism, and dispensational premillennialism—though the earlier nomenclature may have differed. Spurgeon did not preach or write extensively on prophetic themes, but in his sermons and writings he did say enough to produce a clear picture of his position. Despite claims to the contrary, his position was most closely identifiable with that of historic premillennialism in teaching the church would experience the tribulation, the millennial kingdom would be the culmination of God's program for the church, a thousand years would separate the resurrection of the just from that of the unjust, and the Jews in the kingdom would be part of the one people of God with the church. * * * * * In the last hundred years eschatology has probably been the subject of more writings than any other aspect of systematic theology. Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834-92) did not specialize in eschatology, but supporters of almost every eschatological position have appealed to him as an authority to support their views. Given Spurgeon's notoriety, the volume of his writings, and his theological acumen, those appeals are not surprising. A sampling of conclusions will illustrate this point. Lewis A. Drummond states, "Spurgeon confessed to be a pre-millennialist."1 Peter Masters, current 1Lewis A. Drummond, Spurgeon: Prince of Preachers (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1993) 650. -

Glorious Appearing : the End of Days / Tim Lahaye, Jerry B

Visit Tyndale’s exciting Web site at www.tyndale.com Discover the latest about the Left Behind series at www.leftbehind.com Copyright © 2004 by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins. All rights reserved. Cover photograph © by Photodisc/Getty Images. All rights reserved. Authors’ photo copyright © 2003 by Phil Fewsmith. All rights reserved. Left Behind series designed by Catherine Bergstrom Designed by Julie Chen Published in association with the literary agency of Alive Communications, Inc., 7680 Goddard Street, Suite 200, Colorado Springs, CO 80920. Scripture quotations are taken or adapted from the New King James Version. Copyright © 1979, 1980, 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Characters in this novel sometimes speak words that are adapted from various versions of the Bible, including the King James Version and the New King James Version. Left Behind is a registered trademark of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data LaHaye, Tim F. Glorious appearing : the end of days / Tim LaHaye, Jerry B. Jenkins. p. cm. — (Left behind) ISBN 0-8423-3235-9 (hc) — ISBN 0-8423-3237-5 (sc) 1. Steele, Rayford (Fictitious character)—Fiction. 2. Tribulation (Christian eschatology)—Fiction. 3. Rapture (Christian eschatology)—Fiction. 4. End of the world—Fiction. 5. Second coming—Fiction. I. Jenkins, Jerry B. II. Title. PS3562.A315G58 2004 813′.54—dc22 2003027369 Printed in the United States of America 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 87654321 Jezreel Valley Valley of Jehoshapha t? KEY LOCATIONS -

No Longer Left Behind 211

09chap9.qxd 10/1/02 10:21 AM Page 209 No Longer Left Behind Amazon.com, Reader-Response, and the Changing Fortunes of the Christian Novel in America Paul C. Gutjahr Much ink has been spilled on the topic of the uneasy relationship between American Christians and the novel. The vast majority of this scholarship has centered on American Protestantism’s antagonism toward the novel in the early nineteenth century. With few exceptions, the dominant narrative of this relationship goes something like this: American Protestants viewed Wction writing in general, and the novel in particular, as a serious threat to the virtue and well-being of every American up until the 1850s, when their opposition began to gradually erode until it was washed away com- pletely by the astounding popularity of Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, Wrst published in 1880.1 As with so many grand narratives, this one is Xawed. American Protes- tantism has never been a monolithic entity. It has varied according to region- alism, denominationalism, and its connections to other American cultural practices such as science, education, and politics. Perhaps the most im- portant, and most ignored, part of this accepted narrative centers on how The author would like to gratefully acknowledge two fellowship grants that helped bring this article to completion. These grants were awarded by the Center for the Study of Religion at Princeton University under the directorship of Robert Wuthnow and Marie GrifWth and the Christian Scholars Foundation under the directorship of Bernard Draper. 09chap9.qxd 10/1/02 10:21 AM Page 210 210 Book History inXuential conservative elements within American Protestantism continued to show a distrust toward the novel through much of the twentieth century. -

Tribulation Force: the Continuing Drama of Those Left Behind by Tim Lahaye and Jerry B

Tribulation Force: The Continuing Drama of Those Left Behind by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 1996 $12.99, 450 pages ISBN: 08423-2921-8 A Domestic Apocalypse This is the second installment in the Left Behind series. These novels are set in the Last Days and deal, as the name suggests, with those left behind by the pre-tribulation rapture of the saints. Apocalyptic novels based on similar assumptions have been proliferating in recent years (the earliest ones, according to Paul Boyer, appeared in the 1930s), and for their intended readership terms like pre-tribulation rapture require no explanation. However, for this review a few words of explanation might be in order. The eschatological system which the novels presuppose has been increasingly influential in evangelical circles since the end of the Civil War. As the 20th century ends, it may be the most popular Christian eschatological system of any description. To put the matter briefly, pre-tribulationists hold that the saints, meaning all people who have been saved, will be miraculously removed (raptured) from the world in the years leading up to the disastrous events that precede the Second Coming of Christ. These disasters will for the most part occur in a period called the tribulation, which is most commonly expected to last seven years. During that time, the world will be ruled by Antichrist, who will persecute the new crop of saints that rises up in the wake of the rapture. He will also first make peace with the Jews, and then seek to destroy them.