An Analysis of Icann's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internet Filtering: the Politics and Mechanisms of Control

2 Internet Filtering: The Politics and Mechanisms of Control Jonathan Zittrain and John Palfrey It seems hard to believe that a free, online encyclopedia that anyone can edit at any time could matter much to anyone. But just as a bee can fly despite its awkward physiognomy, Wikipedia has become wildly popular and enormously influential despite its unusual format. The topics that Wikipedians write about range more broadly than any other encyclopedia known to humankind. It has more than 4.6 million articles comprising more than a billion words in two hundred languages.1 Many Google search queries will lead to a Wikipedia page among the top search results. Articles in Wikipedia cover the Tiananmen Square pro- tests of 1989, the Dalai Lama, the International Tibet Independence Movement, and the Tai- wan independence movement. Appearing both in the English and the Chinese language versions of Wikipedia—each independently written—these articles have been written to speak from what Wikipedia calls a ‘‘neutral point of view.’’2 The Wikipedians’ point of view on some topics probably does not seem so neutral to the Chinese authorities. Wikipedia has grown so influential, in fact, that it has attracted the attention of China’s cen- sors at least three times between 2004 and 2006.3 The blocking and unblocking of Wikipedia in China—as with all other filtering in China, with- out announcement or acknowledgment—might also be grounded in a fear of the communal, critical process that Wikipedia represents. The purpose of Wikipedia is ‘‘to create and distrib- ute a multilingual free encyclopedia of the highest quality to every single person on the planet in their own language,’’4 and the means of creating it is through engagement of the public at large to contribute what it knows and to debate in earnest where beliefs differ, offering sources and arguments in quasiacademic style. -

Electronic Frontier Foundation November 9, 2018

Before the Department of Commerce National Telecommunications and Information Administration Developing the Administration’s Approach to Consumer Privacy Docket No. 180821780-8780-01 Comments of Electronic Frontier Foundation November 9, 2018 Submitted by: India McKinney Electronic Frontier Foundation 815 Eddy Street San Francisco, CA 94109 USA Telephone: (415) 436-9333 ext. 175 [email protected] For many years, EFF has urged technology companies and legislators to do a better job of protecting the privacy of technology users and other members of the public. We hoped the companies, who have spent the last decade collecting new and increasingly detailed points of information from their customers, would realize the importance of implementing meaningful privacy protections. But this year’s Cambridge Analytica scandal, following on the heels of many others, was the last straw. Corporations are willfully failing to respect the privacy of technology users, and we need new approaches to give them real incentives to do better—and that includes updating our privacy laws. EFF welcomes the opportunity to work with the Department of Commerce in crafting the federal government’s position on consumer privacy. The Request for Comment published in the Federal Register identifies seven main areas of discussion: Transparency, Control, Reasonable Minimization, Security, Access and Correction, Risk Management, and Accountability. These discussion points have been thoroughly analyzed by academics over the past decades, leading to recommendations like the Fair -

A Shared Digital Future? Will the Possibilities for Mass Creativity on the Internet Be Realized Or Squandered, Asks Tony Hey

NATURE|Vol 455|4 September 2008 OPINION A shared digital future? Will the possibilities for mass creativity on the Internet be realized or squandered, asks Tony Hey. The potential of the Internet and the attack, such as that dramatized in web for creating a better, more inno- the 2007 movie Live Free or Die vative and collaborative future is Hard (also titled Die Hard 4.0). discussed in three books. Together, Zittrain argues that security they make a convincing case that problems could lead to the ‘appli- we are in the midst of a revolution ancization’ of the Internet, a return as significant as that brought about to managed interfaces and a trend by Johannes Gutenberg’s invention towards tethered devices, such as of movable type. Sharing many the iPhone and Blackberry, which WATTENBERG VIÉGAS/M. BERTINI F. examples, notably Wikipedia and are subject to centralized control Linux, the books highlight different and are much less open to user concerns and opportunities. innovation. He also argues that The Future of the Internet the shared technologies that make addresses the legal issues and dan- up Web 2.0, which are reliant on gers involved in regulating the Inter- remote services offered by commer- net and the web. Jonathan Zittrain, cial organizations, may reduce the professor of Internet governance user’s freedom for innovation. I am and regulation at the Univ ersity of unconvinced that these technologies Oxford, UK, defends the ability of will kill generativity: smart phones the Internet and the personal com- are just computers, and specialized puter to produce “unanticipated services, such as the image-hosting change through unfiltered con- An editing history of the Wikipedia entry on abortion shows the numerous application SmugMug, can be built tributions from broad and varied contributors (in different colours) and changes in text length (depth). -

Microsoft Corporation As Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioner ————

No. 18-956 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— GOOGLE LLC, Petitioner, v. ORACLE AMERICA, INC., Respondent. ———— On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ———— BRIEF OF MICROSOFT CORPORATION AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER ———— LISA W. BOHL JEFFREY A. LAMKEN MOLOLAMKEN LLP Counsel of Record 300 N. LaSalle St. MICHAEL G. PATTILLO, JR. Chicago, IL 60654 MOLOLAMKEN LLP (312) 450-6700 The Watergate, Suite 660 600 New Hampshire Ave., NW LEONID GRINBERG Washington, DC 20037 MOLOLAMKEN LLP (202) 556-2000 430 Park Ave. [email protected] New York, NY 10022 (212) 607-8160 Counsel for Amicus Curiae :,/621(3(635,17,1*&2,1&± ±:$6+,1*721'& TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Interest of Amicus Curiae ......................................... 1 Summary of Argument ............................................... 3 Argument ...................................................................... 6 I. Innovation in Today’s Computer Industry Depends on Collaborative Development and Seamless Interoperability—Both of Which Require Reuse of Functional Code .............................. 7 A. Innovation in the Modern Computer Industry Relies on Collaborative Development ..................... 7 B. Interoperability Is a Key Component of Technological Innovation Today ....................................... 10 C. Reuse of Functional Software Code, Including APIs, Is Critical To Promoting Collaborative Development and Interoperability ......... 12 II. Courts Have Long Applied a Flexible Fair Use Doctrine To Address Software’s Unique Nature ............................. 15 A. Software’s Collaborative and Functional Elements Distinguish It from Traditional Creative Works Subject to Copyright Protection ............. 16 B. A Flexible Fair Use Doctrine Is Essential To Promoting Collaboration and Interoperability in Modern Software Development— As Courts Have Long Recognized .......... 18 (i) ii TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued Page C. -

Reconciling a Global Internet and Local Law

Research Publication No. 2003-03 5/2003 Be Careful What You Ask For: Reconciling a Global Internet and Local Law Jonathan Zittrain This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Berkman Center for Internet & Society Research Publication Series: http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/publications The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract_id=395300 Be Careful What You Ask For: Reconciling a Global Internet and Local Law Jonathan Zittrain† We used to speak accurately of the Internet, a single logical network of entities only a click away from each other, no matter how distant in physical space. That was certainly the ambitious intention of those who designed it; they sought to integrate lots of existing little networks, running on a variety of physical media, into a coherent whole. They succeeded, and the resulting network and corresponding protocols absorbed almost every other more localized or proprietized network design effort. A globalized Internet running on open protocols meant that users could disregard both their own physical location and that of anyone they traded bits with; an occasional slow-to-respond (even while lightly-trafficked) Web site might be the only betrayal of physical distance online for the average user. Web site operators, in turn, embraced the idea that setting up a single site would expose its contents to the entire Net-connected populace, wherever it might be geographically found. This cherished fact of Internet life promptly spawned a complementary set of problems loosely categorized as “jurisdictional.” At their core lay the fact that perceived serious harm – to one’s reputation, digital property, peace of mind, or computer network – could now easily originate at a distance and follow a path in between accuser and accused that traversed the physical territories of any number of sovereigns. -

Haggart EFF and the Political Economy of the American Digital

1 The Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Political Economy of the American Digital Rights Movement Abstract: As one of the world’s most prominent (if not the most prominent) digital-rights group, and one with a reputation for principled stands, EFF’s views on digital-platform regulation have an outsized influence on policy options not only in the United States, but abroad. Systematically outlining EFF’s digital political economy thus helps to highlight how it defines the issue, and whose interests it promotes. To analyze the EFF’s economic ideology, this paper proposes a five- point framework for assessing the political economy of knowledge that draws on Susan Strange’s theories of structural power and the knowledge structure. It focuses on the control of key forms of knowledge, the role of the state and borders, and attitudes toward surveillance. The paper applies this framework primarily to four years (2015-2018) of EFF blog postings in its annual “Year in Review” series on its “Deeplinks” blog (www.eff.org/deeplinks), drawing out the specific themes and focuses of the organization, including the relative prevalence of economic versus non-economic (such as, for example, state surveillance) issues. The revealed ideology – favouring American-based self-regulation, individual responsibility for privacy, relative support for corporate surveillance, minimalist intellectual property protection, and free cross-border data flows – mirrors the interests of the large American internet platforms. Blayne Haggart Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Brock University St. Catharines, Canada Research Fellow Centre for Global Cooperation Research University of Duisburg-Essen Duisburg, Germany [email protected] Paper presented at the annual International Studies Association Meeting, Toronto, ON, March 27-30, 2019 2 Draft paper. -

Opendns 1 Opendns

OpenDNS 1 OpenDNS OpenDNS Type DNS Resolution Service Founded 2005 Headquarters San Francisco, California Key people David Ulevitch (Founder & CEO) [1] Employees 20 [2] Website OpenDNS.com OpenDNS is a Domain Name System (DNS) resolution service. OpenDNS extends DNS adding features such as misspelling correction, phishing protection, and optional content filtering. It provides an ad-supported service[3][4] "showing relevant ads when we [show] search results" and a paid advertisement-free service. Services DNS OpenDNS offers DNS resolution as an alternative to using Internet service providers' DNS servers. There are OpenDNS servers in strategic locations, and they also employ a large cache of the domain names.. OpenDNS has adopted and supports DNSCurve.[5] OpenDNS provides the following recursive nameserver addresses[6] for public use, mapped to the nearest operational server location by anycast routing: • 208.67.222.222 (resolver1.opendns.com) • 208.67.220.220 (resolver2.opendns.com) • 208.67.222.220 [6] • 208.67.220.222 [6] IPv6 addresses (experimental)[7] • 2620:0:ccc::2 • 2620:0:ccd::2 Other features include a phishing filter, domain blocking and typo correction (for example, typing "example.og" instead of "example.org"). OpenDNS maintains a list of malicious sites and blocks access to them when a user tries to access them through their service. OpenDNS also run a service called PhishTank for users to submit and review suspected phishing sites. The name OpenDNS refers to the DNS concept of being open, where queries from any source are accepted. It is not related to open source software; the service is based on closed-source software.[8] OpenDNS earns a portion of its revenue by resolving a domain name to an OpenDNS server when the name is not otherwise defined in DNS. -

What Larry Doesn't Get: a Libertarian Response to Lessig's Code And

What Larry Doesn’t Get: A Libertarian Response to Lessig’s Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace Independent Institute Working Paper #21 David Post February 2000 What Larry Doesn't Get: A Libertarian Response to Code, and Other Laws of Cyberspace Version Dated January 5, 2000 David G. Post1 As I was preparing this essay and organizing my thoughts about Lawrence Lessig's Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace,2 I was asked to speak at a panel discussion about the problem of unwanted and unsolicited e-mail ("spam") at Prof. Lessig's home institution, Harvard Law School's Berkman Center for Internet and Society.3 The discussion focussed on one particular anti-spam institution, the "Mail Abuse Prevention System" (MAPS); Paul Vixie, the developer and leader of MAPS, was also a participant at this event. MAPS attacks the problem of spam by coordinating a kind of group boycott by Internet service providers (ISPs). It operates, roughly, as follows.4 The managers of MAPS create a list -- the "Realtime Blackhole List" (RBL) -- of ISPs who are, in their view, fostering the distribution of spam. MAPS has its own definition of "fostering the distribution of spam"; it means, for example, providing "spam support services" (e.g., hosting web pages that are listed as destination addresses in bulk emails, providing e-mail forwarders or auto-responders that can be used by bulk emailers), or allowing "open- 1Associate Professor of Law, Temple University Beasley School of Law; [email protected]. Many thanks to Dawn Nunziato and David Johnson for illuminating conversations about earlier drafts of this essay, to Bill Scheinler for his always-helpful research assistance, and to Larry Lessig, for sharing his thoughts on these matters (as well as a searchable electronic version of an early draft of his manuscript) with me. -

Protecting Fundamental Rights Online in the Algorithmic Society

From Constitutional Freedoms to the Power of the Platforms: Protecting Fundamental Rights Online in the Algorithmic Society Giovanni De Gregorio* Summary: 1. Introduction. – 2. From Public to Private as from Atoms to Bits: the Reasons for a Governance Shift. – 3. Delegated Exercise of Quasi-Public Powers Online. 3.1 The Online Content Management. 3.2 The Right to Be Forgotten Online. – 4. Autonomous Exercise of Quasi- Public Powers Online. Towards a private constitutional order or an absolute regime? – 5. Solutions and Perspectives. 5.1 An Old-School Solution: Nudging Online Platforms to Behave as Public Actors. 5.2 An Innovative Solution: Enforcement of Fundamental Rights. – 6. Conclusion: Digital Humanism v Techno-Authoritarianism. 1. Introduction In recent decades, globalisation has challenged the boundaries of constitutional law by calling traditional legal categories into question.1 The internet has played a pivotal role in this process.2 On the one hand, this new protocol of communication has enabled the expanded exercise of individuals' fundamental rights such as freedom of expression.3 On the other hand, unlike other ground-breaking channels of communication, the cross-border nature of the internet has weakened the power of constitutional states, not only in terms of the territorial application of sovereign powers vis-à-vis other states but also with regard to the protection of fundamental rights in the online environment. It should come as no surprise that, from a transnational constitutional perspective, one of the main concerns of states is the limitations placed on their powers to address global phenomena occurring outside their territory.4 The development of the internet has allowed new businesses to exploit the opportunities deriving from the use of a low-cost global communication technology for delivering services without any physical burden, regardless of their location. -

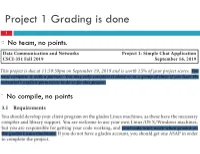

Project 1 Grading Is Done

Project 1 Grading is done 1 No team, no points. No compile, no points Recap 2 The IPv4 Shortage 3 Problem: consumer ISPs typically only give one IP address per-household ! Additional IPs cost extra ! More IPs may not be available NAT and DHCP NAT + DHCP Basic NAT Operation 4 Private Network Internet Source: 192.168.0.1 Source: 66.31.210.69 Dest: 74.125.228.67 Dest: 74.125.228.67 Private Address Public Address 192.168.0.1:2345 74.125.228.67:80 192.168.0.1 66.31.210.69 74.125.228.67 Source: 74.125.228.67 Source: 74.125.228.67 Dest: 192.168.0.1 Dest: 66.31.210.69 Port-forwarding 5 DHCP: Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol 6 Let’s say that a ISP has X customers, How many IPs does it need to have? X? Goal: allow host to dynamically obtain its IP address from network server when it joins network can renew its lease on address in use allows reuse of addresses (only hold address while connected/“on”) support for mobile users who want to join network (more shortly) DHCP Client-Server 7 DHCP 223.1.1.0/24 server 223.1.1.1 223.1.2.1 223.1.1.2 arriving DHCP 223.1.1.4 223.1.2.9 client needs address in this 223.1.2.2 network 223.1.1.3 223.1.3.27 223.1.2.0/24 223.1.3.1 223.1.3.2 DHCP Client-Server 8 DHCP server: 223.1.2.5 DHCP discover arriving client src : 0.0.0.0, 68 Broadcast:dest.: 255.255.255.255,67 is there a DHCP serveryiaddr: out 0.0.0.0 there? transaction ID: 654 DHCP offer src: 223.1.2.5, 67 Broadcast:dest: 255.255.255.255, I’m a DHCP 68 server!yiaddrr: Here’s 223.1.2.4 an IP transaction ID: 654 addresslifetime: you3600 cansecs use DHCP request src: 0.0.0.0, 68 dest:: 255.255.255.255, 67 Broadcast:yiaddrr: 223.1.2.4 OK. -

Jonathan Zittrain's “The Future of the Internet: and How to Stop

The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Jonathan L. Zittrain, The Future of the Internet -- And How to Stop It (Yale University Press & Penguin UK 2008). Published Version http://futureoftheinternet.org/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4455262 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page i The Future of the Internet— And How to Stop It YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page ii YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iii The Future of the Internet And How to Stop It Jonathan Zittrain With a New Foreword by Lawrence Lessig and a New Preface by the Author Yale University Press New Haven & London YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iv A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org. The cover was designed by Ivo van der Ent, based on his winning entry of an open competition at www.worth1000.com. Copyright © 2008 by Jonathan Zittrain. All rights reserved. Preface to the Paperback Edition copyright © Jonathan Zittrain 2008. Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

Signposts in Cyberspace: the Domain Name System and Internet Navigation

Prepublication Copy—Subject to Further Editorial Correction Signposts in Cyberspace: The Domain Name System and Internet Navigation Committee on Internet Navigation and the Domain Name System: Technical Alternatives and Policy Implications Computer Science and Telecommunications Board Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, D.C. www.nap.edu Prepublication Copy—Subject to Further Editorial Correction THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. Support for this project was provided by the U.S. Department of Commerce and the National Science Foundation under Grant No. ANI-9909852 and by the National Research Council. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the Commerce Department. International Standard Book Number Cover designed by Jennifer M. Bishop. Copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press, 500 Fifth Street, N.W., Lockbox 285, Washington, D.C. 20055, (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313 in the Washington metropolitan area. Internet, http://www.nap.edu Copyright 2005 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Prepublication Copy—Subject to Further Editorial Correction The National Academy of Sciences is a private, nonprofit, self-perpetuating society of distinguished scholars engaged in scientific and engineering research, dedicated to the furtherance of science and technology and to their use for the general welfare.