A SPACE for DIALOGUE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olin Levi Warner

237 East Palace Avenue Santa Fe, NM 87501 800 879-8898 505 989-9888 505 989-9889 Fax [email protected] James Brooks (American Painter, 1906-1992) A painter of both Social Realism and Abstract Expressionism and part of the so-called New York School, James Brooks did many large-scale paintings that expressed a sense of cosmic space as though a high-powered telescope were penetrating space so deeply that one feels the color, the form, and the surge of movement. He used much black, so that darkness seemed equal to the other colors of his canvases and conveyed a sense of void amongst floating and colliding bright colors. He was born in St. Louis, Missouri, and during his childhood, moved frequently Photograph courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University throughout the Southwest. In the mid and late 1920s in Dallas, Texas, he attended Southern Methodist University and the Dallas Art Institute where he studied with Martha Simkins. In 1926, he moved to New York City and worked as a commercial lettering artist, while taking night classes at the Art Students League from 1927 to 1930. From 1931 to 1934, he traveled and painted in the American West and Southwest, painting in a Social Realist style. Between 1936 and 1942, he worked on murals for the WPA Federal Art Project including ones for Queensborough Public Library, Woodside Branch Library, and La Guardia In the historic Spiegelberg House . Palace Avenue at Paseo de Peralta 237 East Palace Avenue Santa Fe, NM 87501 800 879-8898 505 989-9888 505 989-9889 Fax [email protected] Airport. -

Postwar Abstraction in the Hamptons August 4 - September 23, 2018 Opening Reception: Saturday, August 4, 5-8Pm 4 Newtown Lane East Hampton, New York 11937

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Montauk Highway II: Postwar Abstraction in the Hamptons August 4 - September 23, 2018 Opening Reception: Saturday, August 4, 5-8pm 4 Newtown Lane East Hampton, New York 11937 Panel Discussion: Saturday, August 11th, 4 PM with Barbara Rose, Lana Jokel, and Gail Levin; moderated by Jennifer Samet Mary Abbott | Stephen Antonakos | Lee Bontecou | James Brooks | Nicolas Carone | Giorgio Cavallon Elaine de Kooning | Willem de Kooning | Fridel Dzubas | Herbert Ferber | Al Held | Perle Fine Paul Jenkins | Howard Kanovitz | Lee Krasner | Ibram Lassaw | Michael Lekakis | Conrad Marca-Relli Peter Moore |Robert Motherwell | Costantino Nivola | Alfonso Ossorio | Ray Parker | Philip Pavia Milton Resnick | James Rosati | Miriam Schapiro | Alan Shields | David Slivka | Saul Steinberg Jack Tworkov | Tony Vaccaro | Esteban Vicente | Wilfrid Zogbaum EAST HAMPTON, NY: Eric Firestone Gallery is pleased to announce the exhibition Montauk Highway II: Postwar Abstraction in the Hamptons, opening August 4th, and on view through September 23, 2018. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Hamptons became one of the most significant meeting grounds of like-minded artists, who gathered on the beach, in local bars, and at the artist-run Signa Gallery in East Hampton (active from 1957-60). It was an extension of the vanguard artistic activity happening in New York City around abstraction, which constituted a radical re-definition of art. But the East End was also a place where artists were freer to experiment. For the second time, Eric Firestone Gallery pays homage to this rich Lee Krasner, Present Conditional, 1976 collage on canvas, 72 x 108 inches and layered history in Montauk Highway II. -

Oral History Interview with James Brooks

Oral history interview with James Brooks Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with James Brooks AAA.brooks65 Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with James Brooks Identifier: AAA.brooks65 -

Oral History Interview with James Brooks, 1965 June 10 and June 12

Oral history interview with James Brooks, 1965 June 10 and June 12 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview DS: Dorothy Seckler JB: James Brooks DS: This is Dorothy Seckler interviewing James Brooks in East Hampton, or near East Hampton, this is actually Amagansett Springs. And this is June 10th, 1965, I'd like to begin by filling in some of your background, your early years, your childhood, where you were born, and so on. JB: All right. My father had been a schoolteacher. I think he was born in Georgia. Then he ended up with a school of his own in Tupelo, Mississippi, I believe. I don't know the sequence of events after that. He had been married once before he married my mother. In the meantime he had turned into a traveling salesman of soda fountains. And they met at the Fair in St. Louis, I believe, the Louisiana Purchase Fair maybe. And they were married there. Then he was traveling around a good deal. There were four children, my older brother, myself, and two sisters younger - my older brother was born in Burton, Arkansas. I was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1906; one sister was born in Oklahoma City, and another was born in Denver, Colorado. I left St. Louis when I was five months old so I don't have much knowledge of St. -

A Finding Aid to the James Brooks and Charlotte Park Papers, 1909-2010, Bulk 1930-2010, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the James Brooks and Charlotte Park Papers, 1909-2010, bulk 1930-2010, in the Archives of American Art Catherine S. Gaines 2015 May 14 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 5 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Materials, 1924-1995........................................................... 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1928-1990s.................................................................. 8 Series 3: Interviews, 1965-1990............................................................................... 9 Series 4: Writings, -

A Finding Aid to the Elisabeth Zogbaum Papers Regarding Franz Kline, 1892-Circa 2005, Bulk 1930-1990, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Elisabeth Zogbaum Papers regarding Franz Kline, 1892-circa 2005, bulk 1930-1990, in the Archives of American Art Rihoko Ueno 2018/03/27 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Franz Kline Biographical Material, 1925-1962, circa 1998........................ 5 Series 2: Correspondence, 1929-1998.................................................................... 7 Series 3: Estate of Franz Kline, 1955-1991........................................................... 10 Series 4: Franz Kline Foundation, -

The Making of an Educational Film As a Means of Communicating Our

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1972 The akm ing of an educational film as a means of communicating our contemporary fine ra t culture. Terry Krumm University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Krumm, Terry, "The akm ing of an educational film as a means of communicating our contemporary fine ra t culture." (1972). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2605. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2605 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MAKIHG OF AN EDUCATIONAL FILM AS A MEANS OF COMMUNICATING OUR CONTEMPORARY FINE ART CULTURE A dissertation presented Terry Krumm Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education April 1972 Major Subject! Educational Media and Technology THE MAKING OF AN EDUCATIONAL FILM AS A MEANS OF COMMUNICATING OUR CONTEMPORARY FINE ART CULTURE A Dissertation ty Terry KruF^m The film is available in original form and appears under separate cover as an addendum to the dissertation. Approved as to style and content byi 'DwighV W. Allen, Dean 0/^ > OksT Dr. Daniel Member Dr. David G. Coffin^, yvlembe^/ In memory of B C A CK N C WLEDGEIV'JIM TS I would like to acknowledge the advice and guidance of David Coffing in production of the pilot and disserta- tion films. -

Abstract Expressionism 1 Abstract Expressionism

Abstract expressionism 1 Abstract expressionism Abstract expressionism was an American post–World War II art movement. It was the first specifically American movement to achieve worldwide influence and put New York City at the center of the western art world, a role formerly filled by Paris. Although the term "abstract expressionism" was first applied to American art in 1946 by the art critic Robert Coates, it had been first used in Germany in 1919 in the magazine Der Sturm, regarding German Expressionism. In the USA, Alfred Barr was the first to use this term in 1929 in relation to works by Wassily Kandinsky.[1] The movement's name is derived from the combination of the emotional intensity and self-denial of the German Expressionists with the anti-figurative aesthetic of the European abstract schools such as Futurism, the Bauhaus and Synthetic Cubism. Additionally, it has an image of being rebellious, anarchic, highly idiosyncratic and, some feel, nihilistic.[2] Jackson Pollock, No. 5, 1948, oil on fiberboard, 244 x 122 cm. (96 x 48 in.), private collection. Style Technically, an important predecessor is surrealism, with its emphasis on spontaneous, automatic or subconscious creation. Jackson Pollock's dripping paint onto a canvas laid on the floor is a technique that has its roots in the work of André Masson, Max Ernst and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Another important early manifestation of what came to be abstract expressionism is the work of American Northwest artist Mark Tobey, especially his "white writing" canvases, which, though generally not large in scale, anticipate the "all-over" look of Pollock's drip paintings. -

JAMES BROOKS Painting I Prefer to Know, Works on Canvas from 1950-1958

JAMES BROOKS Painting I Prefer to Know, Works on Canvas from 1950-1958 March 13 – April 27, 2019 23 East 73rd Street N, 1952, Oil, black crayon and powdered pigment on muslin, 38 1/2 x 32 3/4 inches (97.8 x 83.2 cm) “The painting surface has always been the rendezvous of what the painter knows with the unknown, which appears on it for the first time.” ¾JAMES BROOKS, 1955 Van Doren Waxter is pleased to present James Brooks: Painting I Prefer to Know, Works on Canvas from 1950-1958, an exhibition by the masterful and crucial Abstract Expressionist on view at 23 East 73rd Street from March 13 to April 27, 2019. A skilled colorist, Brooks is noted for his approach to creating rhythmic, dynamic works comprised of richly colored and textured visual planes. This suite of paintings was produced during a period of increasing critical acclaim for the artist, and today there is a renewed interest in his art practice. A survey curated by Chief Curator Alicia Longwell is scheduled for 2020 at The Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York. The 1950s were both a highly productive and highly visible decade for the artist who began his career during the Great Depression and moved to New York City in 1926. After serving in the United States Army as an Art Correspondent in the Middle East, Brooks returned to New York in 1945 following the rise of Abstract Expressionism as an established movement. By 1950, he would receive his first of many solo exhibitions at Peridot Gallery in New York; gain inclusion in the Whitney Annual and Carnegie International; and the following year participate in the historic and groundbreaking 9th Street Exhibition (1951) that included Jackson Pollock, Hans Hofmann, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Jack Tworkov, and others. -

Marine Air Terminal Interior

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 25, 1980, Designation List 138 LP-1110 MARINE AIR TERMINAL INTERIOR, main floor interior consisting of the en trance vestibule, the hallway connecting the entrance vestibule to the circular main space, the stairways leading from the main floor to the second floor, the circular main space to the depth of the opening reveals, and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces, including but not limited to, wall, ceiling, and floor surfaces, doors and transoms, aluminum letter signs, attached clock, skylight, and staircase railings; LaGuardia Airport, Queens. Landmark Site: Tax Map Block 926, Lot 1 in part consisting of the land on which the described building is situated. On December 11, 1979, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Marine Air Terminal Interior and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 16). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Three witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. Letters have been received in support of designation. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey made note of its superior jurisdiction. DESCRIPTION A1~ ANALYSIS Hardly more than a decade after Charles Lindbergh's historic 1927 solo flight from New York to Paris, the world's first transatlantic passenger flights were regularly departing from La Guardia Airport's Marine Air Terminal. Designed in the Art Deco style, the Terminal is "modern", serving as an ap propriate introduction to air travel, which struck the general public in the 1930s as both glamorous and adventurous. -

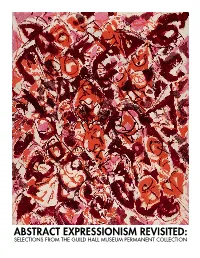

Abstract Expressionism Revisited

ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM REVISITED: SELECTIONS FROM THE GUILD HALL MUSEUM PERMANENT COLLECTION ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM REVISITED: SELECTIONS FROM THE GUILD HALL MUSEUM PERMANENT COLLECTION Joan Marter, PhD 158 Main Street East Hampton, New York 11937 Office: 631-324-0806 Fax: 631-324-2722 guildhall.org Cover image: Lee Krasner Untitled, 1963 Oil on canvas 54 x 46 inches Purchased with aid of funds from the National Endowment for the Arts ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM REVISITED: SELECTIONS FROM THE GUILD HALL MUSEUM PERMANENT COLLECTION is the catalogue for the exhibition curated for Guild Hall by Joan Marter, PhD. The exhibition is on view from October 26 - December 30, 2019 The exhibition at Guild Hall has been made possible through the generosity of its sponsors LEAD SPONSORS: Betty Parsons Foundation, and Lucio and Joan Noto CO-SPONSORS: Barbara F. Gibbs, and the Robert Lehman Foundation All Museum Programming supported in part by The Melville Straus Family Endowment, The Michael Lynne Museum Endowment, Vital Projects Fund, Hess Philanthropic Fund, Crozier Fine Arts, The Lorenzo and Mary Woodhouse Trust, and public funds provided by New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and Suffolk County. guildhall.org ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to Andrea Grover, Executive Director of Guild Hall and the curatorial staff. It was a great pleasure to work with Christina Strassfield, Casey Dalene, and Jess Frost on this exhibition. Special accolades to Jess Frost, Associate Curator/Registrar of the Permanent Collection, who prepared a digitized inventory of the collection that is now available to all members and interested visitors to Guild Hall. -

James Brooks: Familiar World 1942 – 1982 May 3 – June 23, 2017

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE James Brooks: Familiar World 1942 – 1982 May 3 – June 23, 2017 James Brooks, Aamo, 1981. Acrylic and oil on canvas. 20 x 26 inches (50.8 x 66 cm). But I think my whole tendency has been away from a fast moving line either violent or lyrical into something that is slower and denser and more wandering and unknowing –– James Brooks March 15, 2017 (New York, NY) - Van Doren Waxter is pleased to present James Brooks: Familiar World 1942 – 1982, an exhibition of small-scale paintings by the masterful Abstract Expressionist James Brooks. On view from May 3 through June 23, 2017, this historic survey traces the evolution of the artist’s career over a period spanning four decades. James Brooks (1906–1992) began his career as an artist during the Great Depression, moving to New York City in 1926, where he worked as a muralist under the Works Progress Administration and studied representational painting at the Art Students League. His career as an artist was briefly disrupted when he was drafted to serve in the United States Army as an Art Correspondent in the Middle East in 1942. Brooks’ time in the Middle East directly coincided with the rise of Abstract Expressionism as an established movement in the United States. Upon returning to New York in 1945, Brooks turned away from representational painting toward abstraction, drawing inspiration from his friendships with peers such as Jackson Pollock, Philip Guston, and Bradley Walker Tomlin. During the mid-1940s, Brooks’ work was largely influenced by the synthetic Cubism of Picasso and Braque, which is most apparent in the composition of his early paintings, such as Bad Intentions (c.