1 Post-Handover Hong Kong Cinema on Coproduction, Censorship, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(S): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(s): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring 1994), pp. 65-77 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389334 Accessed: 22-12-2015 11:50 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Discourse. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.157.160.248 on Tue, 22 Dec 2015 11:50:37 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The New Hong Kong Cinema and the Déjà Disparu Ackbar Abbas I For about a decade now, it has become increasinglyapparent that a new Hong Kong cinema has been emerging.It is both a popular cinema and a cinema of auteurs,with directors like Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, Allen Fong, John Woo, Stanley Kwan, and Wong Rar-wei gaining not only local acclaim but a certain measure of interna- tional recognitionas well in the formof awards at international filmfestivals. The emergence of this new cinema can be roughly dated; twodates are significant,though in verydifferent ways. -

A Brief Analysis of China's Contemporary Swordsmen Film

ISSN 1923-0176 [Print] Studies in Sociology of Science ISSN 1923-0184 [Online] Vol. 5, No. 4, 2014, pp. 140-143 www.cscanada.net DOI: 10.3968/5991 www.cscanada.org A Brief Analysis of China’s Contemporary Swordsmen Film ZHU Taoran[a],* ; LIU Fan[b] [a]Postgraduate, College of Arts, Southwest University, Chongqing, effects and packaging have made today’s swordsmen China. films directed by the well-known directors enjoy more [b]Associate Professor, College of Arts, Southwest University, Chongqing, China. personalized and unique styles. The concept and type of *Corresponding author. “Swordsmen” begin to be deconstructed and restructured, and the swordsmen films directed in the modern times Received 24 August 2014; accepted 10 November 2014 give us a wide variety of possibilities and ways out. No Published online 26 November 2014 matter what way does the directors use to interpret the swordsmen film in their hearts, it injects passion and Abstract vitality to China’s swordsmen film. “Chivalry, Military force, and Emotion” are not the only symbols of the traditional swordsmen film, and heroes are not omnipotent and perfect persons any more. The current 1. TSUI HARK’S IMAGINARY Chinese swordsmen film could best showcase this point, and is undergoing criticism and deconstruction. We can SWORDSMEN FILM see that a large number of Chinese directors such as Tsui Tsui Hark is a director who advocates whimsy thoughts Hark, Peter Chan, Xu Haofeng , and Wong Kar-Wai began and ridiculous ideas. He is always engaged in studying to re-examine the aesthetics and culture of swordsmen new film technology, indulging in creating new images and film after the wave of “historic costume blockbuster” in new forms of film, and continuing to provide audiences the mainland China. -

Hong Kong 20 Ans / 20 Films Rétrospective 20 Septembre - 11 Octobre

HONG KONG 20 ANS / 20 FILMS RÉTROSPECTIVE 20 SEPTEMBRE - 11 OCTOBRE À L’OCCASION DU 20e ANNIVERSAIRE DE LA RÉTROCESSION DE HONG KONG À LA CHINE CO-PRÉSENTÉ AVEC CREATE HONG KONG 36Infernal affairs CREATIVE VISIONS : HONG KONG CINEMA, 1997 – 2017 20 ANS DE CINÉMA À HONG KONG Avec la Cinémathèque, nous avons conçu une programmation destinée à célé- brer deux décennies de cinéma hongkongais. La période a connu un rétablis- sement économique et la consécration de plusieurs cinéastes dont la carrière est née durant les années 1990, sans compter la naissance d’une nouvelle génération d’auteurs. PERSISTANCE DE LA NOUVELLE VAGUE Notre sélection rend hommage à la créativité persistante des cinéastes de Hong Kong et au mariage improbable de deux tendances complémentaires : l’ambitieuse Nouvelle Vague artistique et le film d’action des années 1980. Bien qu’elle soit exclue de notre sélection, il est utile d’insister sur le fait que la production chinoise 20 ANS / FILMS KONG, HONG de cinéastes et de vedettes originaires de Hong Kong, tels que Jackie Chan, Donnie Yen, Stephen Chow et Tsui Hark, continue à caracoler en tête du box-office chinois. Les deux films Journey to the West avec Stephen Chow (le deuxième réalisé par Tsui Hark) et La Sirène (avec Stephen Chow également) ont connu un immense succès en République Populaire. Ils n’auraient pas été possibles sans l’œuvre antérieure de leurs auteurs, sans la souplesse formelle qui caractérise le cinéma de Hong Kong. L’histoire et l’avenir de l’industrie hongkongaise se lit clairement dans la carrière d’un pionnier de la Nouvelle Vague, Tsui Hark, qui a rodé son savoir-faire en matière d’effets spéciaux d’arts martiaux dans ses premières productions télévisuelles et cinématographiques à Hong Kong durant les années 70 et 80. -

Johnnie to Kei-Fung's

JOHNNIE TO KEI-FUNG’S PTU Michael Ingham Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2009 Michael Ingham ISBN 978-962-209-919-7 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Pre-Press Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface vii Acknowledgements xi 1 Introducing the Film; Introducing Johnnie — 1 ‘One of Our Own’ 2 ‘Into the Perilous Night’ — Police and Gangsters 35 in the Hong Kong Mean Streets 3 ‘Expect the Unexpected’ — PTU’s Narrative and Aesthetics 65 4 The Coda: What’s the Story? — Morning Glory! 107 Notes 127 Appendix 131 Credits 143 Bibliography 147 ●1 Introducing the Film; Introducing Johnnie — ‘One of Our Own’ ‘It is not enough to think about Hong Kong cinema simply in terms of a tight commercial space occasionally opened up by individual talent, on the model of auteurs in Hollywood. The situation is both more interesting and more complicated.’ — Ackbar Abbas, Hong Kong Culture and the Politics of Disappearance ‘Yet many of Hong Kong’s most accomplished fi lms were made in the years after the 1993 downturn. Directors had become more sophisticated, and perhaps fi nancial desperation freed them to experiment … The golden age is over; like most local cinemas, Hong Kong’s will probably consist of a small annual output and a handful of fi lms of artistic interest. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

DP TRIANGLE.Indd

DISTRIBUTION WILD SIDE FILMS 42, rue de Clichy 75009 Paris Tél : 01 42 25 82 00 Fax : 01 42 25 82 10 www.wildside.fr RELATIONS PRESSE LE PUBLIC SYSTEME CINEMA Céline Petit & Annelise Landureau 40, rue Anatole France 92594 Levallois-Perret cedex Tel : 01 41 34 23 50 / 22 01 Fax : 01 41 34 20 77 [email protected] [email protected] www.lepublicsystemecinema.com www.triangle-lefi lm.com CADAVRE EXQUIS : Jeu créé par les surréalistes en 1920 qui consiste à faire composer une phrase, ou un dessin, par plusieurs personnes sans qu’aucune d’elles puisse tenir compte de la collaboration ou des collaborations précédentes. En règle générale un cadavre exquis est une histoire commencée par une personne et terminée par plusieurs autres. Quelqu’un écrit plusieurs lignes puis donne le texte à une autre personne qui ajoute quelques lignes et ainsi de suite jusqu’à ce que quelqu’un décide de conclure l’histoire. DISTRIBUTION STOCK Wild Side Films Distribution Service Tél : 01 42 25 82 00 STOCKS COPIES ET PUBLICITÉ Fax : 01 42 25 82 10 Grande Région Ile-de-France www.wildside.fr 24, Route de Groslay 95204 Sarcelles WILD SIDE FILMS DIRECTION DE LA DISTRIBUTION présente Marc-Antoine Pineau COPIES Tél. : 01 34 29 44 21 [email protected] Fax : 01 39 94 11 48 [email protected] Dossier de presse imprimé en papier recyclé PROGRAMMATION Philippe Lux PUBLICITÉ [email protected] Tél. : 01 34 29 44 26 Fax : 01 34 29 44 09 [email protected] MÉDIAS Le premier film réalisé sur le principe du jeu du cadavre exquis Christophe Laduche par les trois maîtres du cinéma de Hong Kong [email protected] LYON 25, avenue Beauregard 69150 Decines DIRECTRICE TECHNIQUE 35MM Brigitte Dutray Tél. -

Written & Directed by and Starring Stephen Chow

CJ7 Written & Directed by and Starring Stephen Chow East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor IHOP Public Relations Block Korenbrot PR Sony Pictures Classics Jeff Hill Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Jessica Uzzan Judy Chang Leila Guenancia 853 7th Ave, 3C 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-265-4373 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 212-247-2948 fax 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 1 Short Synopsis: From Stephen Chow, the director and star of Kung Fu Hustle, comes CJ7, a new comedy featuring Chow’s trademark slapstick antics. Ti (Stephen Chow) is a poor father who works all day, everyday at a construction site to make sure his son Dicky Chow (Xu Jian) can attend an elite private school. Despite his father’s good intentions to give his son the opportunities he never had, Dicky, with his dirty and tattered clothes and none of the “cool” toys stands out from his schoolmates like a sore thumb. Ti can’t afford to buy Dicky any expensive toys and goes to the best place he knows to get new stuff for Dicky – the junk yard! While out “shopping” for a new toy for his son, Ti finds a mysterious orb and brings it home for Dicky to play with. To his surprise and disbelief, the orb reveals itself to Dicky as a bizarre “pet” with extraordinary powers. Armed with his “CJ7” Dicky seizes this chance to overcome his poor background and shabby clothes and impress his fellow schoolmates for the first time in his life. -

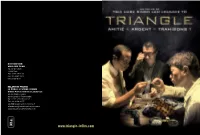

Tsui Hark Ringo Lam Johnnie To

TSUI HARK LOUIS KOO A legendary producer and director, Tsui Hark is one of Hong Kong cinema’s most influential figures. A pioneer of the 80’s Hong Kong New — AH FAI Wave film movement, Tsui Hark immediately caught the attention of critics with his innovative style and techniques. “Butterfly Murders” Singer, actor, model – Louis Koo is one of Hong Kong’s most popular Chanteur, acteur, mannequin – Louis Koo est l’une des plus grandes (1979) and “Dangerous Encounters: 1st Kind”(1980) pushed the boundary of Hong Kong genre films as well as the limit of the censors. celebrities. He began his film career in the mid-90’s and has acted in stars de Hong Kong. Il commence sa carrière au milieu des années 90 Following the creation of Film Workshop in 1984, he directed and produced a series of successful commercial films that initiated the so-called over 40 movies such as Wilson Yip’s “Bullet Over Summer”(1999), Tsui et joue dans plus de 40 films, dont « Bullets Over Summer » (1999) de “golden era” of Hong Kong cinema. Films including “A Chinese Ghost Story”(1987), “Swordsman”(1990), and “Once Upon A Time In China” Hark’s “Legend of Zu 2”(2001) and Derek Yee’s “Lost In Time”(2003). Wilson Yip, « La Légende de Zu 2 » (2001) de Tsui Hark et « Lost In (1991) established Tsui Hark's dominance across Asia. After directing two films in Hollywood, he returned to Hong Kong in the mid-90’s Over the past couple of years, he has forged a close working relationship Time » (2003) de Derek Yee. -

IFFAM 2943 – East & West Masterpieces on the Big Screen

SUPPLEMENT THU 07.12.2017 SHOWING INSIDE Crossfire Special Presentation Flying Daggers FAQs II Int’l Film Festival EAST & WEST MASTERPIECES ON THE BIG SCREEN he Crossfire feature of the IFFAM, described by organizers as a “retrospective” element of the festival, will showcase six master films selected by renowned filmmakers. From the black and white motion pictures of the 1940s to Kubrick’s sci-fi masterpiece “2001: Space Odyssey” of the 60s and the psychological thriller “Silence of the Lambs”, the genre films hail from THollywood and Asia, the latter represented with seminal works from Kurosawa, Johnnie To and Derek Yee. International Film Festival & Awards Macao CROSSFIRE: A RETROSPECTIVE OF CINEMA FROM KUBRICK TO KUROSAWA The Crossfire feature of the IFFAM will showcase six master films selected by renowned filmmakers. The pictures will be shown on the big screen at The Cinematheque Passion, from December 8 to 12 ONE NITE IN MONGKOK Mongkok, Hong Kong: a densely populated hot- KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS MAD DETECTIVE bed of criminal activity. Mainland Chinese farm Hotshot Inspector Ho seeks out his former boss Bun boy Lai Fu is a hired killer who enters the neon-lit English actors Dennis Price and Sir Alec Guinness underbelly of this infamous district. When he res- star in this 1949 black comedy. Price plays the for help in cracking a serial murder case. Bun, a gifted criminal profiler, went mad years ago and now lives cues a call girl from gangsters, the two must go lead role of Louis d’Ascoyne Mazzini, ninth in line on the run from policemen and triads alike. -

Market Research 2020

THE ITALIAN TRADE COMMISSION HONG KONG MARKET RESEARCH FILM 2020 SEPTEMBER F O S B A C K G R O U N D E Hong Kong Current Market Overview L 2 T S T A T I S T I C B A Hong Kong Box Office & Market Trend T 4 N S T A T I S T I C 5 Audio & Visual Equipment Industry E L O C A L F I L M I N D U S T R Y T 7 Loca Industry and Distribution G L O B A L D I S T R I B U T I O N N 8 International Investment and Recognition T E L E V I S I O N I N D U S T R Y O 10 Local TV Industry T R A D E S H O W C 1 1 Hong Kong FILMART A S S O C I A T I O N S 12 Hong Kong Trade Associations (Film Sector) R E F E R E N C E 13 Source and Reference BACKGROUND: V O L U M E 3 , I S S U E 3 HONG KONG CURRENT MARKET OVERVIEW Business Shock Under COVID-19 CINEMA CLOSED DUE TO CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC Under the tightened social distancing policies announced by the HKSAR government to fight against the coronavirus, cinemas were previously closed twice from March 27 to May 5 and July 15 to August 27 Hong Kong box office receipts plunged by more than 70% in the first six months of 2020 as audiences stayed away and cinemas shut down amid the coronavirus pandemic. -

Punished (2011) Dopo Il Sequestro Della Figlia L'imprenditore Wong Ricorre a Ogni Mezzo Per Stanare I Rapitori E Vendicarsi

Punished (2011) Dopo il sequestro della figlia l'imprenditore Wong ricorre a ogni mezzo per stanare i rapitori e vendicarsi. Un film di Wing-Cheong Law con Anthony Chau-Sang Wong, Richie Ren, Janice Man, Maggie Cheung Ho Yee, Candy Lo, Charlie Cho. Genere Thriller durata 94 minuti. Produzione Hong Kong 2011. Quando la figlia di un magnate viene trovata morta per overdose di cocaina, lui cercherà in ogni modo di vendicarla. Emanuele Sacchi - www.mymovies.it Mentre il mogul Johnnie To sembra sempre più incline alle deviazioni nel campo della commedia e a pregevoli estetismi cinefili, lo zoccolo duro della sua creatura, ossia la Milkyway Image, resta fedele al noir made in Hong Kong. Law Wing-cheong è un fedelissimo di To, uno che da sempre sopperisce con l'umiltà dell'allievo coscienzioso alla mancanza di personalità. Quando si è trattato di uscire dagli schemi di genere ('2 Become 1') i risultati sono stati disastrosi, ma 'Punished' appartiene a quell'artigianato action di qualità che un tempo era prerogativa di Hong Kong. Quasi "coreano" nella sua ossessione per la vendetta, il film di Law delega buona parte della sua forza dirompente all'interpretazione ancora una volta superba di Anthony Wong: un personaggio tutt'altro che monodimensionale quello del palazzinaro miliardario che paga a caro prezzo le manchevolezze della sua dimensione privata. L'insaziabile sete di vendetta dapprima ne esalta i lati più ferini e pare allontanarlo da ogni residuo di umanità, per poi portarlo a uno spietato confronto con se stesso. Indicativo in questo senso il cambio di registro di Wong, alle prese con i rovesciamenti della sottotrama sugli scontri tra imprenditori edili e abitanti dei Nuovi Territori di Hong Kong.