Old Museum Building Conservation Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Claiming Domestic Space: Queensland's Interwar Women

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Volz, Kirsty (2017) Claiming domestic space: Queensland’s interwar women architects and their labour saving devices. Lilith: a Feminist History Journal, 2017(23), pp. 105-117. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/114447/ c Australian Women’s History Network This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// search.informit.com.au/ documentSummary;dn= 042103273078994;res=IELHSS Claiming Domestic Space: Queensland’s interwar women architects and their labour saving devices Abstract The interwar period was a significant era for the entry of women into the profession of architecture. -

Media 2 World Science Festival Brisbane 2016 Media Release 3-5

CONTENTS ____________________________________________________________________________ World Science Festival Brisbane overview 1 Festival information for media 2 World Science Festival Brisbane 2016 media release 3-5 FESTIVAL PROGRAM Wednesday 9 - Sunday 13 March 2016 6-12 PERFORMANCE Light Falls: Space, Time and an Obsession of Einstein 13-14 Dear Albert 15-16 SIGNATURE EVENTS FROM NEW YORK Dawn of the Human Age 17 To Infinity and Beyond: The Accelerating Universe 18 Madness Redefined: Creativity, Intelligence and the Dark Side of the Mind 19 Reality since Einstein 20 Alien Life: Will We Know It When We Find It? 21 The Moral Math of Robots 22 CONVERSATIONS AND TALKS Can We Save Our Precious Reefs in Time? 23 Last days of Mephisto - Forensic and Ballistic Science 24 Playing for Time: Music and Memory 25 Breakfast with the Brians 26 Pioneers in Science 27 The First Scientists – Aboriginal Science Panel 28 Chasing Down the Comet 29 Under the Microscope 30 Great Moments in Science with Dr Karl 31 Where Worlds Collide: Science, Values and Ethics 32 Science and Story: Getting it Write 33 Going with the Floe: The Changing Shape of Sea Ice 34 The Thomas Conservation Oration 2016 35 Film and Discussion Panel - The Martian with Andy Thomas and Pam Conrad 36 Catching up with the Jetsons: Cities in 2050 37 SALONS Discovering the Deep 38 Robots: The New Eco Warriors 39 Shining New Light on Dark Matter 40 Alzheimer’s: Don’t forget your genes 41 Rosetta Rendezvous 42 1.5 Degrees of Separation 43 Winning Ways: The Use and Abuse of Performance Enhancing -

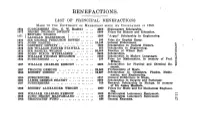

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE to the UNIVERSITY Oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION in 1853

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. .. £866 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Prizes for History and Education. 1871 j LA^HL^MACKmNON I 100° "ArSUS" S«h°lar8hiP ln Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 666 Scholarship in Engineering. 1876 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 6000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS 160 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,887 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics, and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 6217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 8900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship In Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT 1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. BENEFACTIONS (Continued). 1908 TEACHING STAFF £1160 General Expenses. oo including Professor Sponcer £2riS Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1908 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1908 GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2600 Books. 1004 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarship!!. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND . -

Land Administration Building Conservation Management Plan Prepared By: Urbis Pty Ltd

5HPRYH IURP 4XHHQV*DUGHQV WKURXJKRXW POD VOLUME 3: ATTACHMENT D.10: FORMER LAND ADMINISTRATION BUILDING CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN PREPARED BY: URBIS PTY LTD Any items struck out are not approved. $0(1'(',15(' %\ K McGill 'DWH 20 December 20177 3/$16$1''2&80(176 UHIHUUHGWRLQWKH3'$ '(9(/230(17$33529$/ $SSURYDOQR DEV2017/846 'DWH 21 December 2017 DATE OF ISSUE: 24.11.2017 REVISION: 15 Copyright 2017 © DBC 2017 This publication is subject to copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. DESTINATION BRISBANE CONSORTIUM www.destinationbrisbaneconsortium.com.au CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Background........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Queen’s Wharf Brisbane....................................................................................................................... 2 1.3. Purpose................................................................................................................................................. 2 1.4. Site Location ........................................................................................................................................ -

Enoggera State School

Heritage Information Please contact us for more information about this place: [email protected] -OR- phone 07 3403 8888 Enoggera State School Key details Addresses At 239 South Pine Road, Enoggera, Queensland 4051 Type of place State school Period World War I 1914-1918 Style Bungalow Lot plan L1052_SP137336 Key dates Local Heritage Place Since — 1 July 2005 Date of Information — January 2005 Construction Roof: Corrugated iron; Walls: Timber Date of Information — January 2005 Page 1 People/associations Thomas Pye (Architect) Criterion for listing (A) Historical; (B) Rarity; (D) Representative; (G) Social Enoggera State School was opened in 1871 after local residents lobbied for the erection of a permanent school in the area. The oldest school building on the site today, built in 1916, was constructed after the original timber classrooms were deemed insufficient to accommodate the 200 or so students attending the school by that time. The new building was designed in such a way as to allow for future extensions to accommodate the expected growth of the school. The 1870s buildings were later removed from the site and the original school building is now part of the Enoggera Memorial Hall in Wardell Street. History In September 1870 a public meeting at the Enoggera Hotel (now the Alderley Arms) resolved to raise subscriptions and lobby the Board of Education for the establishment of a state school at Enoggera. Two single acre blocks of land were donated by Mr T. Corbett and Mr J. Mooney, and after further fund raising tenders were called for the new school in May 1871. -

Attachment D.6: Queen's Gardens Conservation Management Plan

POD VOLUME 3: ATTACHMENT D.6: 4XHHQV 1R LQ 4XHHQV*DUGHQV UHPRYHWKURXJKRXW QUEEN’S GARDENS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN PREPARED BY: URBIS PTY LTD Any items struck out are not approved. $0(1'(',15(' %\K McGill 'DWH20 December 2017 3/$16$1''2&80(176 UHIHUUHGWRLQWKH3'$ '(9(/230(17$33529$/ $SSURYDOQR DEV2017/846DEV2017/846 'DWH 2121 DecemberDecember 20172017 DATE OF ISSUE: 24.11.2017 REVISION: 12 Copyright 2017 © DBC 2017 This publication is subject to copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. DESTINATION BRISBANE CONSORTIUM www.destinationbrisbaneconsortium.com.au CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Background........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Queen’s Wharf Brisbane....................................................................................................................... 1 1.3. Purpose................................................................................................................................................. 2 1.4. Site Location ........................................................................................................................................ -

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas PYE

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas PYE [1862 – 1930] Colonel Pye was elected to Life Membership of the Club – possibly after 1919 and before 1928. Colonel Pye was President of the Club in 1919 Thomas Pye was born in Ormskirk, Lancashire on 15 June 1862. His father was Edward Pye [1830-1880] a farmer; and his mother was Ellen (née Hewitt) [1833-1881] He was the fifth of their six children – with four elder sisters and a younger brother. We thank the History Interest Group and other volunteers who have researched and prepared these Notes .The series will be progressively expanded and developed. They are intended as casual reading for the benefit of Members, who are encouraged to advise of any inaccuracies in the material. Please do not reproduce them or distribute them outside of the Club membership. File: HIG/Biographies/Pye Page 1 Thomas trained as an architect in England and emigrated to Sydney in January 1883 on the ship “John Elder.” In Sydney in 1883, Thomas married Emily Ruth (née Ivy). She was born in 1857 in Manchester and died in 1928 in Harrogate, Yorkshire. She had emigrated to Sydney in 1883. Thomas’ sister Ann Jane Pye was a witness at their wedding, and in 1900 his younger brother John Hewitt Pye was married in Sydney – indicating that other family members had moved to Australia. Before her death, the Census of 1881 shows Thomas‘ widowed mother Ellen keeping a lodging house in Omskirk. In the same Census, Emily Ivy’s widowed mother also kept a lodging house in a nearby street. -

This Sampler File Contains Various Sample Pages from the Product. Sample Pages Will Often Include: the Title Page, an Index, and Other Pages of Interest

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently This sampler file includes the title page, and various sample pages from this volume. This file is fully searchable (read search tips page) Archive CD Books Australia exists to make reproductions of old books, documents and maps available on CD to genealogists and historians, and to co-operate with family history societies, libraries, museums and record offices to scan and digitise their collections for free, and to assist with renovation of old books in their collection. -

Eminent Queensland Engineers

Eminent Queensland Engineers Editor R. L. Whitmore Published by The Institution of Engineers, Australia Queensland Division 1984 Cover picture: Professor R.H.W. Hawken Copyright: Queensland Division Institution of Engineers, Australia ill 11 The Institution of Engineers, Australia is not responsible, as an organization, for the facts and opinions advanced in this publication. ISIIN () 85814 138 8 Printed by Consolidated Printers Pty. Ltd. Typesetting by ~ ~ Word for Word" - Secretarial Services. EMINENT QUEENSLAND ENGINEERS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION. •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 3 CONTRIBUTORS. • •••• ..... •••••• ••• ••• •• •• •• • ••• ..... •••• • •• 5 BIOGRAPHIES 1. Colonel Sir Albert Axon. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. • • • • • • • • • • 6 2. EeG.C. Barton 8 •••••• '" • • • • • • 3. A.A. Boyd ••••••••••••••••••• co • • • • • • • 10 4 A.B. Brady ••••••• co •••••••••••••••••••• .. • • • • • • • • • • 12 5. Joseph Brady co • • • • • • • • • • • • • 14 6. A.B. Corbett ••••••••••••••••• '" • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 16 7. W.H. Corbould • • • • •• ••••••••••••••••••••••••• •• • • • 18 8. E.S. Cornwall. •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 20 9. G.A. Cowling.. ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 22 10. W.J. Cracknell. ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 24 11. A.E. Cullen. •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 26 12. R.T.. Darker. • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. ••••••••••••••••••••••• 28 13. Colonel D.E. Evans •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 30 14. A.J. Goldsmith. • . • • .. ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• -

Pod Volume 3: Attachment D.2: Former Government Printing Office Conservation Management Plan Prepared By: Urbis Pty Ltd

POD VOLUME 3: ATTACHMENT D.2: FORMER GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN PREPARED BY: URBIS PTY LTD Any items struck out are not approved. $0(1'(',15(' %\K McGill 'DWH20 December 2017 3/$16$1''2&80(176 UHIHUUHGWRLQWKH3'$ '(9(/230(17$33529$/ $SSURYDOQR DEV2017/846 'DWH 21 December 2017 DATE OF ISSUE: 24.11.2017 REVISION: 12 Copyright 2017 © DBC 2017 This publication is subject to copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publishers. DESTINATION BRISBANE CONSORTIUM www.destinationbrisbaneconsortium.com.au CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Background........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Queen’s Wharf Brisbane....................................................................................................................... 2 1.3. Purpose................................................................................................................................................. 2 1.4. Site Location ........................................................................................................................................ -

Cultural Heritage Report

CULTURAL HERITAGE REPORT for the proposed Airport Link Study Area Southeast Queensland for Report commissioned by SKM/ CONNELL WAGNER Joint Venture Partners For Brisbane City Council MAY 2006 This assessment was undertaken by ARCHAEO Cultural Heritage Services Pty. Ltd., the Centre for Applied History and Heritage Studies, University of Queensland, and John Hoysted (heritage architect), ERM Australia. Contact details are: ARCHAEO Cultural Heritage Services 369 Waterworks Road, Ashgrove, Brisbane PO Box 333, The Gap, Brisbane, 4061 Tel: 3366 8488 Fax: 3366 0255 CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Scope of Study 2 2 Approach to Study 4 2.1 Determining Cultural Heritage Significance 5 2.1.1 Historical Heritage Significance 5 2.1.2 Significant Aboriginal Cultural Heritage 7 2.2 Legislation Applicable to Cultural Heritage 8 2.2.1 National Legislation 8 2.2.2 State Legislation 9 2.3 Nature of Cultural Heritage 9 2.3.1 Historical Heritage Sites and Places 10 2.3.2 Known Aboriginal Areas 11 2.3.3 Archaeological Sites 11 3 The Physical and Cultural Landscape 12 4 Aboriginal Cultural Heritage 15 4.1 The Archaeological Record 15 4.2 Historical Accounts of Aboriginal Life 17 4.3 History of Contact Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Cultures 24 4.4 Conclusions 26 5 Historical Heritage 27 5.1 Suburb Histories 27 5.1.1 Windsor 27 5.1.2 Lutwyche 38 5.1.3 Wooloowin and Kalinga 43 5.2 Previous Consultancy Reports 47 5.2.1 Study Area Corridor 47 5.2.2 Study area 2 – Possible Spoil Placement Sites 49 5.3 Conclusions 51 6 Results of Heritage Research 53 6.1 Historical Heritage Sites and Places of Known Significance 53 6.1.1 Former Windsor Shire Council Chambers 56 6.1.2 Windsor State School Campus 56 6.1.3 Windsor War Memorial Park 57 6.1.4 Kirkston 57 6.1.5 Oakwal 58 6.1.6 Boothville or Monte Video 58 6.1.7 Craigellachie 59 6.1.8 BCC Tramways Substation No. -

Annual Report 2018-19

BOARD OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 22 August 2019 The Honourable Leeanne Enoch MP Minister for Environment and the Great Barrier Reef Minister for Science and Minister for the Arts GPO BOX 5078 BRISBANE QLD 4001 Dear Minister I am pleased to submit for presentation to the Parliament the Annual Report 2018–2019 and financial statements for the Board of the Queensland Museum. I certify that this annual report complies with: • the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009, and • the detailed requirements set out in the Annual report requirements for Queensland Government agencies. A checklist outlining the annual reporting requirements can be found on page 78 of this annual report. Yours sincerely Professor Margaret Sheil AO Chair Board of the Queensland Museum BOARD OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 1 CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 2 VISION 2 MISSION 2 PURPOSE 3 QUEENSLAND MUSEUM NETWORK 7 BOARD OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM 8 CHAIR’S OVERVIEW 9 CEO’S OVERVIEW 10 HIGHLIGHTS AND ACHIEVEMENTS 12 WORLD SCIENCE FESTIVAL BRISBANE 13 AWARDS, FELLOWSHIPS AND RECOGNITION 14 BACKGROUND 14 GOVERNMENT OBJECTIVES FOR THE COMMUNITY 15 STRATEGIC PLAN 2018–2022 15 OPERATIONAL PLAN 2018–2019 16 OPERATING ENVIRONMENT 16 STRATEGIC RISKS 16 STRATEGIC OPORTUNITIES 18 OUTCOMES 18 PERFORMANCE MEASURES 20 STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES 31 GOVERNANCE 31 MANAGEMENT AND STRUCTURE 35 BOARD OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM 40 FINANCE, AUDIT AND RISK MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE 41 QUEENSLAND