Upwardly Mobile in a Branch-Office City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cameron Davies Director

CAMERON DAVIES DIRECTOR Cameron is an urban designer and architect with a developed understanding of cities, towns, and the diverse range of building types within them. Since 1995, Cameron has designed and directed significant greenfield and urban regeneration design projects in Queensland. As an architect, he has been responsible for the design and coordination of a broad range of projects including education, mixed-use developments, sustainable multi-residential housing, aged care facilities, data centres, industrial and university buildings. He has highly developed visual communication skills and significant experience with both private and public sector clients. He is also one of the foremost enquiry by design facilitators in Australia and regularly uses this skill to engage stakeholders in the design process. Through his work, and his masters thesis research, he has a well developed understanding of sustainable urban growth management. ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS Architecture Bachelor of Architecture, University of Queensland (1994) - Project director, Signature Hotel & Restaurant, Coffs Harbour, BH Group Masters in Built Environment, Urban Design, Queensland University of Technology (2003) - Project Director, Gold Coast Rapid Transit Station, Early works design — GCRT - Project Director - Family Housing, Hannay Street, Moranbah, BMA PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS - Project Director, Noosa North Shore ‘Beach Houses’ — Petrac Queensland Registered Architect (1996) - Project Director, Springfield Data Centre — Springfield New South Wales Registered -

Claiming Domestic Space: Queensland's Interwar Women

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Volz, Kirsty (2017) Claiming domestic space: Queensland’s interwar women architects and their labour saving devices. Lilith: a Feminist History Journal, 2017(23), pp. 105-117. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/114447/ c Australian Women’s History Network This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// search.informit.com.au/ documentSummary;dn= 042103273078994;res=IELHSS Claiming Domestic Space: Queensland’s interwar women architects and their labour saving devices Abstract The interwar period was a significant era for the entry of women into the profession of architecture. -

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT June 19, 2017 Compiled by the Music Network© FREE SIGN UP

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT June 19, 2017 Compiled by The Music Network© FREE SIGN UP Hot 100 Aircheck spins, weighted with audience data & time of spins #1 hot 100 despacito (remix) 1 Luis Fonsi | UMA DESPACITO (REMIX) There's nothing holdin' me b... Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee ft. Justin Bieber | UMA 2 Shawn Mendes | UMA galway girl 3 Ed Sheeran | WMA From Latin hit to commercial radio triumph, Luis Fonsi’s Despacito (Remix) has pushed its way to the i'm the one top of the Hot 100, ousting DJ Khaled’s I’m The One, which falls to #4. This has opened the door for 4 DJ Khaled | SME/UMA Shawn Mendes’ There’s Nothing Holdin’ Me Back and Ed Sheeran’s persistent Galway Girl to take up Malibu the remaining spots in the Top 3. 5 Miley Cyrus | SME 6 Strip That down Liam Payne’s Strip That Down can’t be overlooked at #6. The One Direction star seems to be Liam Payne | EMI gathering serious momentum as the official acoustic version of the track is serviced to radio this week. 7 Slow hands Niall Horan | EMI His buddies Harry Styles and Niall Horan aren’t far behind. Styles’ Sign Of The Times restores its spot something just like this 8 The Chainsmokers & Coldp... in the Top 10 this week, landing at #9 after peaking at #3 at the beginning of May, while Horan’s Slow sign of the times Hands remains parked at #7 for another week. 9 Harry Styles | SME your song 10 Rita Ora | WMA that's what i like 11 Bruno Mars | WMA Bad Liar #1 MOST ADDED TO RADIO 12 Selena Gomez | UMA The cure 2U 13 Lady Gaga | UMA David Guetta ft. -

Local Heritage Register

Explanatory Notes for Development Assessment Local Heritage Register Amendments to the Queensland Heritage Act 1992, Schedule 8 and 8A of the Integrated Planning Act 1997, the Integrated Planning Regulation 1998, and the Queensland Heritage Regulation 2003 became effective on 31 March 2008. All aspects of development on a Local Heritage Place in a Local Heritage Register under the Queensland Heritage Act 1992, are code assessable (unless City Plan 2000 requires impact assessment). Those code assessable applications are assessed against the Code in Schedule 2 of the Queensland Heritage Regulation 2003 and the Heritage Place Code in City Plan 2000. City Plan 2000 makes some aspects of development impact assessable on the site of a Heritage Place and a Heritage Precinct. Heritage Places and Heritage Precincts are identified in the Heritage Register of the Heritage Register Planning Scheme Policy in City Plan 2000. Those impact assessable applications are assessed under the relevant provisions of the City Plan 2000. All aspects of development on land adjoining a Heritage Place or Heritage Precinct are assessable solely under City Plan 2000. ********** For building work on a Local Heritage Place assessable against the Building Act 1975, the Local Government is a concurrence agency. ********** Amendments to the Local Heritage Register are located at the back of the Register. G:\C_P\Heritage\Legal Issues\Amendments to Heritage legislation\20080512 Draft Explanatory Document.doc LOCAL HERITAGE REGISTER (for Section 113 of the Queensland Heritage -

Fall 2018 the WESTERN WAY CONTENTS FEATURES Tales of the West 27 6 Jim Wilson in the Crosshairs Sons of the Pioneers

Founder From e President... Bill Wiley Ocers Marvin O’Dell, Someone told me recently that they don’t join or get President involved with the IWMA because the same people win the Jerry Hall, Executive V.P. Robert Fee, awards year aer year. It’s not the rst time I’ve heard this, V.P. General Counsel but I thought this time I would check to see if that is, in fact, Yvonne Mayer, Secretary true. Here’s what I discovered (you can see these same results Diana Raven, Treasurer at the IWMA Web site): Executive Director In the Male Performer of the Year category, there have Marsha Short been six dierent winners in the last ten years; the female Board of Directors counterpart in that category has had six dierent winners in John Bergstrom Richard Dollarhide Marvin O’Dell the last eleven years. Ok, there’s a little room to gripe there, Robert Fee but not much. It’s certainly not the same winner every year. Juni Fisher IWMA President Belinda Gail In the Songwriter of the Year category there have been Jerry Hall eight dierent winners in the last ten years, and the Song of the Year category shows 14 Judy James Robert Lorbeer dierent winners in the last 16 years. Yvonne Mayer e Traditional Duo/Group category has had 10 dierent winners in the last eleven years. Marvin O’Dell Theresa O’Dell Western Swing Album of the Year? Nine dierent winners in the past ten years. Instrumentalist of the Year? Eight dierent players have taken home the award in the past 2018 Board Interns 10 years. -

Inner Brisbane Heritage Walk/Drive Booklet

Engineering Heritage Inner Brisbane A Walk / Drive Tour Engineers Australia Queensland Division National Library of Australia Cataloguing- in-Publication entry Title: Engineering heritage inner Brisbane: a walk / drive tour / Engineering Heritage Queensland. Edition: Revised second edition. ISBN: 9780646561684 (paperback) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Brisbane (Qld.)--Guidebooks. Brisbane (Qld.)--Buildings, structures, etc.--Guidebooks. Brisbane (Qld.)--History. Other Creators/Contributors: Engineers Australia. Queensland Division. Dewey Number: 919.43104 Revised and reprinted 2015 Chelmer Office Services 5/10 Central Avenue Graceville Q 4075 Disclaimer: The information in this publication has been created with all due care, however no warranty is given that this publication is free from error or omission or that the information is the most up-to-date available. In addition, the publication contains references and links to other publications and web sites over which Engineers Australia has no responsibility or control. You should rely on your own enquiries as to the correctness of the contents of the publication or of any of the references and links. Accordingly Engineers Australia and its servants and agents expressly disclaim liability for any act done or omission made on the information contained in the publication and any consequences of any such act or omission. Acknowledgements Engineers Australia, Queensland Division acknowledged the input to the first edition of this publication in 2001 by historical archaeologist Kay Brown for research and text development, historian Heather Harper of the Brisbane City Council Heritage Unit for patience and assistance particularly with the map, the Brisbane City Council for its generous local history grant and for access to and use of its BIMAP facility, the Queensland Maritime Museum Association, the Queensland Museum and the John Oxley Library for permission to reproduce the photographs, and to the late Robin Black and Robyn Black for loan of the pen and ink drawing of the coal wharf. -

QUEENSLAND CULTURAL CENTRE Conservation Management Plan

QUEENSLAND CULTURAL CENTRE Conservation Management Plan JUNE 2017 Queensland Cultural Centre Conservation Management Plan A report for Arts Queensland June 2017 © Conrad Gargett 2017 Contents Introduction 1 Aims 1 Method and approach 2 Study area 2 Supporting documentation 3 Terms and definitions 3 Authorship 4 Abbreviations 4 Chronology 5 1 South Brisbane–historical overview 7 Indigenous occupation 7 Penal settlement 8 Early development: 1842–50 8 Losing the initiative: 1850–60 9 A residential sector: 1860–1880 10 The boom period: 1880–1900 11 Decline of the south bank: 1900–1970s 13 2 A cultural centre for Queensland 15 Proposals for a cultural centre: 1880s–1960s 15 A new art gallery 17 Site selection and planning—a new art gallery 18 The competition 19 The Gibson design 20 Re-emergence of a cultural centre scheme 21 3 Design and construction 25 Management and oversight of the project 25 Site acquisition 26 Design approach 27 Design framework 29 Construction 32 Costing and funding the project 33 Jubilee Fountain 34 Shared facilities 35 The Queensland Cultural Centre—a signature project 36 4 Landscape 37 Alterations to the landscape 41 External artworks 42 Cultural Forecourt 43 5 Art Gallery 49 Design and planning 51 A temporary home for the Art Gallery 51 Opening 54 The Art Gallery in operation 54 Alterations 58 Auditorium (The Edge) 61 6 Performing Arts Centre 65 Planning the performing arts centre 66 Construction and design 69 Opening 76 Alterations to QPAC 79 Performing Arts Centre in use 80 7 Queensland Museum 87 Geological Garden -

Planning and Environment Court of Queensland

PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENT COURT OF QUEENSLAND CITATION: Body Corporate for Mayfair Residences Community Titles Scheme 31233 v Brisbane City Council & Anor [2017] QPEC 22 PARTIES: BODY CORPORATE FOR MAYFAIR RESIDENCES COMMUNITY TITLES SCHEME 31233 (appellant) v BRISBANE CITY COUNCIL (respondent) and THE TRUSTEE FOR THE ATHOL PLACE PROPERTY TRUST (co-respondent) FILE NO/S: 3467 of 2016 DIVISION: Planning and Environment Court PROCEEDING: Planning and Environment Appeal ORIGINATING COURT: Brisbane DELIVERED ON: 26 April 2017 DELIVERED AT: Brisbane HEARING DATE: 23, 24 and 28, 29, 31 March 2017 and 5 April 2017 JUDGE: Kefford DCJ ORDER: The appeal will, in due course, be dismissed. I will adjourn the further hearing to allow for the formulation of conditions. CATCHWORDS: PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENT – appeal against approval of a development application for material change of use – proposed development for re-use of heritage place, office, health care services and food and drink outlet – whether there is conflict occasioned by bulk and scale – whether there is conflict with the planning intent for the Petrie Terrace and Spring Hill Neighbourhood Plan area - whether there will be unacceptable amenity and character impacts – whether cultural heritage significance is protected - whether there are sufficient grounds to approve the proposed development despite conflict with the planning scheme – whether there is a need for the proposed development 2 Sustainable Planning Act 2009 (Qld), s 314, s 324, s 326, s 462, s 493, s 495 Acland Pastoral Co Pty -

BHG Events 1981-2017

BHG Events 1981-2017 Date Title Activity Venue Speakers Papers BHG Pub n 1981 28 March Public, Practical and Personal Workshop Bardon Professional John Laverty Local government in Brisbane: An historiographical view P1 Brisbane Development Centre Richard Allom The built environment as an historical resource P1 Tom Watson Schooling in urban context P1 John Wheeler Imagination versus documentation in urban evolution P1 Geoff Cossins Tracing the Brisbane water supply P1 Fred Annand SEQEB and the perpetual record P1 John Kerr The evolving railways of Brisbane P1 Colin Sheehan The mosaic of source material P1 John Cole Deciding research strategies for historical society: The P1 lifecourse approach Meredith Walker Delineating the character of the Queensland house P1 27 May Settling the Suburbs: New Seminar St Thomas’ Anglican Helen Gregory Early occupation of land in south-west Brisbane P1 Approaches to Community History Hall, Toowong Helen Bennett Studying a community concept: Late nineteenth century Toowong 27 July Brisbane’s Industrial Monuments Walk/drive Brisbane city: Windmill (Ray Whitmore) tour to Botanic Gardens 9 August Illustrated talk on City life in Historic Lecture UQ Forgan Smith Mark Girouard City life in historic Bath Bath Building 13 September Investigating Wolston House (1853) – Talk, tour Wolston House, Wacol Ray Oliver Investigating Wolston House (1853) a talk and tour about the house, property and owners 24 October The Historical Ups and Downs of Talk, walk/ Caxton Street Hall Rod Fisher The historical ups and downs of -

![[12] Extra Gazette.Fm](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8556/12-extra-gazette-fm-2188556.webp)

[12] Extra Gazette.Fm

[55] Queensland Government Gazette Extraordinary PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. 368] Friday 16 January 2015 [No. 12 56 QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No. 12 [16 January 2015 Electoral Act 1992 The Electoral Commission of Queensland hereby declares the following to be mobile polling booths for the purposes of the 2015 State General Election to be held on Saturday 31 January 2015. Electoral District Name and Address of Institution ALBERT Gold Coast Homestead Nursing Centre, 142 Reserve Road, Upper Coomera QLD 4209 ALGESTER Algester Lodge, 117 Dalmeny Street, Algester QLD 4115 Clive Burdeu Aged Care Service Hillcrest, 46 Middle Road, Hillcrest QLD 4118 RSL Care Carrington Retirement Community, 16 Blairmount Street, Parkinson QLD 4115 Regis Boronia Heights, 271 Middle Road, Greenbank QLD 4124 St Paul de Chartres Residential Aged Care, 12 Fedrick Street, Boronia Heights QLD 4124 ASHGROVE Regis Treetops Manor, 6 Kilbowie Street, THE GAP QLD 4061 ASPLEY AVEO Aspley Court, 100 Albany Creek Road, Aspley QLD 4034 Aveo Bridgeman Downs, 42 Ridley Road, Bridgeman Downs QLD 4035 Compton Gardens Retirement Village, 97 Albany Creek Road, Aspley QLD 4034 Holy Spirit Home, 736 Beams Road, Carseldine QLD 4034 Katandra Serviced Apartments, 109 Albany Creek Road, Aspley QLD 4034 Opal Raynbird Place, 40 Raynbird Place, Carseldine QLD 4034 P M Village, 1929 Gympie Road, Bald Hills QLD 4036 BARRON RIVER Blue Care - Glenmead Village, 15 Short Street, Redlynch QLD 4870 Masonic Care Queensland - Cairns, 82-120 McManus Street, Whitfield QLD 4870 BEAUDESERT Beaudesert Hospital, 64 Tina Street, Beaudesert QLD 4285 Boonah Hospital, Leonard Street, Boonah QLD 4310 Fassifern Aged Care Services- Boonah, Harold Stark Avenue, Boonah QLD 4310 PresCare- Roslyn Lodge, 24 Main Western Road, North Tamborine QLD 4272 Star Gardens Star Aged Living P.L., 14 Brooklands Drive, Beaudesert QLD 4285 Wongaburra Society, 210 Brisbane Street, Beaudesert QLD 4285 16 January 2015] QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No. -

Register of Architects & Non Practising Architects

REGISTER OF ARCHITECTS & NON PRACTISING ARCHITECTS Copyright The Board of Architects of Queensland supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of information. However, copyright protects this document. The Board of Architects of Queensland has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically , provided it is for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation; this material remains unaltered and the Board of Architects of Queensland is recognised as the owner. Enquiries should be addressed to: [email protected] Register As At 29 June 2021 In pursuance of the provision of section 102 of Architects Act 2002 the following copy of the Register of Architects and Non Practicing Architects is published for general information. Reg. No. Name Address Bus. Tel. No. Architects 5513 ABAS, Lawrence James Ahmad Gresley Abas 03 9017 4602 292 Victoria Street BRUNSWICK VIC 3056 Australia 4302 ABBETT, Kate Emmaline Wallacebrice Architecture Studio (07) 3129 5719 Suite 1, Level 5 80 Petrie Terrace Brisbane QLD 4000 Australia 5531 ABBOUD, Rana Rita BVN Architecture Pty Ltd 07 3852 2525 L4/ 12 Creek Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Australia 4524 ABEL, Patricia Grace Elevation Architecture 07 3251 6900 5/3 Montpelier Road NEWSTEAD QLD 4006 Australia 0923 ABERNETHY, Raymond Eric Abernethy & Associates Architects 0409411940 7 Valentine Street TOOWONG QLD 4066 Australia 5224 ABOU MOGHDEB EL DEBES, GHDWoodhead 0403 400 954 Nibraz Jadaan Level 9, 145 Ann Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Australia 4945 ABRAHAM, -

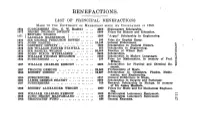

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE to the UNIVERSITY Oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION in 1853

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. .. £866 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Prizes for History and Education. 1871 j LA^HL^MACKmNON I 100° "ArSUS" S«h°lar8hiP ln Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 666 Scholarship in Engineering. 1876 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 6000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS 160 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,887 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics, and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 6217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 8900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship In Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT 1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. BENEFACTIONS (Continued). 1908 TEACHING STAFF £1160 General Expenses. oo including Professor Sponcer £2riS Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1908 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1908 GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2600 Books. 1004 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarship!!. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND .