Minogue Helena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ten Years of Pottery in New Zealand

10 YEARS OF POTTERY IN NEW ZEALANDW CANCELLED Hamilton City Libraries 10 YEARS OF POTTERY IN NEW ZEALAND Helen Mason This is the story of the growth of the I making is satisfying because it combines pottery movement in this country and the learning of skills with the handling of of the people mainly involved in it over such elemental materials as clay and the past ten years as seen through my fire, so that once involved there is no | eyes as Editor of the New Zealand end to it. In it the individual looking for Potter magazine. a form of personal expression can find fulfillment, but it also lends itself to Interest in pottery making has been a group activity and is something construc- the post war development in most of tive to do together. civilised world, and by the time it reach- ed us was no longer a craft revival but I believe that with all this pottery rather a social phenomenon. Neverthe— activity, stemming as it does from the less there has been a large element of lives of ordinary men and women, a missionary zeal in our endeavours. seedbed has been formed out of which something real and vital is beginning to We are a young nation with enough grow. I have tried to record the history leisure, education and material security of these last ten years for I feel that to start looking for a culture of our own, they are important in the understanding and we want more human values than of what is to come. -

The Haptic Dimension of Ceramic Practice: Ways of Knowing

School of Media, Creative Arts and Social Inquiry The Haptic Dimension of Ceramic Practice: Ways of Knowing Alana Carol McVeigh This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University October 2020 i ii The Haptic Dimension of Ceramic Practice: Ways of Knowing Declaration Alana Carol McVeigh iii Acknowledgements My heartfelt thanks to my supervisors, Dr Ann Schilo, Dr Anna Nazzari and Dr Susanna Castleden for their generosity of knowledge, immeasurable support, encouragement and guidance. I would like to acknowledge my colleagues for their support and friendship. In particular I would like to thank Dr Monika Lukowska- Appel not only for her support but also her design knowledge. I acknowledge Dr Dean Chan for his detailed attention to copyediting. I gratefully acknowledge my family Damien, Regan, Ashlea and Maiko for your understanding and support. Most importantly, to Chaz for your unrelenting encouragement, belief, love and for teaching me of courage. Finally, this journey has been for, Bailey, Kyuss, Tiida, Jai, Lumos and Otoko No Akachan. iv The Haptic Dimension of Ceramic Practice: Ways of Knowing Abstract My research seeks to unravel how an influx of multiple streams of tacit knowledge and sensory awareness has impacted upon an Australian approach to ceramic art making. Through a combination of creative practice and exegesis, I consider how experiential knowledge, amassed over time by observing, replicating and doing, built a visual, cognitive and sensual vocabulary that has become embodied into a visceral form of making: a form of making and awareness that entered Australian ceramic studio practice from China, Japan, Korea and Britain primarily during the 1940s–1960s. -

Michael Cardew – (1901-1983)

MICHAEL CARDEW – (1901-1983) The names of Michael Cardew and Bernard Leach are almost invariably linked. Cardew was Leach‟s “first and best student”1 and Cardew stated that his three years at St. Ives were “the most important part of my education as a potter.”2 Yet the two men were very different, both personally and artistically, and Cardew‟s legacy to the world of ceramic art stands firmly on its own. Among the highlights of his long career are his establishment of potteries in England which revitalized the English slipware tradition, and the parallel establishment of potteries in Africa where he introduced the methods of Leach and in return brought to the western world the traditions of African pottery. He is also noted as a gifted teacher, one who led by example rather than formal instruction, and whose total and passionate involvement with pottery left a lasting impression on his students and apprentices. Cardew authored a number of articles, and his Pioneer Pottery, a classic in the field, is still being reprinted. 1. Bernard Leach. “Introduction.” Michael Cardew: A Collection of Essays. London: Crafts Advisory Committee, 1976. 2. Michael Cardew. A Pioneer Potter: an Autobiography. London: Collins, 1988 ARTIST’S STATEMENT - MICHAEL CARDEW “If you are lucky, and if you live long enough, and if you trust your materials and you trust your instincts, you will see things of beauty growing up in front of you, without you having anything to do with it.”1 “ You see, nobody can teach anybody anything, you must teach yourself. You just keep trying and repeating a shape and then you begin to feel confident…yes, yes, I can do this. -

New Zealand Potter Volume 29 Number 2 1987

New Zealand Potter ‘ Volume 29, Number 2, 1987 coon NEWS / New Zealand Potter FOR Volume 29, Number 2, 1987 iiz ISSN POTI'ERS 0028—8608 Price $5.50 includes GST Cover: Royce McGlashen “Just Teasing” porcelain. Photo by Haru Sameshima Kevin Griffin is pleased to announce that CONTENTS he has taken Editor: Howard Williams over the business of Design: Warren Matthews General Manager: 2 Through the Filter Press t5‘le)f/‘L McSkimming’s Clay Des Thompson 3 Letters to the Editor 4 NZSP Insurance Scheme — Stephen Western and as owner/ operator, that it will A Communication Associates Ltd 5 Exhibition Calendar rot“ publication, also publishers of the 6 Penny Evans and Julie COHiS New Zealand Journal onriculture 8 Up the Creek with Barry 7 Peter Lange operate under the new name . and the New Zealand Gardener. 11 Neil Gardiner MM” 12 Fletcher Challenge Pottery Award 1987 NM 14 Another Viewpoint — Howard S. Williams 15 Gisborne Summer Craft School / 16 Nelson Potters Summer Exhibition 18 The Rim 7 Michael Hieber Distribution: Direct 2] Firing while you sleep from the PllbliSher 3} 22 Don’t Lift by the Handles 7 Joanna Paul P-O- BOX 2505’ Christchurch 23 NZSP 29th National Exhibition SOUTHERN CLAYS After AUZUS‘ 1937, from: 26 Wellington Potters 29th Annual Exhibition P-O- Box 381’ 29 Overseazure PROCESSCRS & SUPPLIERS OF POTTERY CLAY II — Barry Brickell Auckland. 36 Art Awards 37 Vic Evans — Peter Gibbs Typeset and produced by Communication Associates Ltd, 39 Jerry Rothman School 40 Colin Pearson 210 Antigua St., Christchurch. — Leo King 42 Collectors Gallery — Peter Gibbs Printed by Potters Market Wyatt & Wilson Limited AVAILABLE FROM: Christchurch South Street Gallery C.C.G. -

2012 Gallery Catalogue

POTTERY AND PRIMITIVISM A selling show of early slipware by Michael Cardew and Ray Finch Long Room Gallery High Street Winchcombe 24th November to 1st December 2012 1 TEL: 01242 602 319 E MAIL: [email protected] JOHN EDGELER & ROGER LITTLE PRESENT A SELLING EXHIBITION POTTERY AND PRIMITIVISM THE MODERN MOVEMENT SLIPWARES OF MICHAEL CARDEW AND FOLLOWERS 24th November to 1st December 2012 inclusive 9.30am to 5.00pm (from midday on first day) Long Room Gallery, Queen Anne House, High Street, Winchcombe, Gloucestershire, GL54 5LJ Telephone: 01242 602319 Website: www.cotswoldsliving.co.uk 2 Show terms and conditions Condition: Due to their low fired nature, slipwares are prone to chipping and flaking, and all the pots for sale were originally wood fired in traditional bottle or round kilns, with all the faults and delightful imperfections entailed. We have endeavoured to be as accurate as possible in our descriptions, and comment is made on condition where this is materially more than the normal wear and tear of 80 to 100 years. For the avoidance of any doubt, purchasers are recommended to inspect pots in person. Payment: Payment must be made in full on purchase, and pots will normally be available for collection at the close of the show, in this case on Saturday 1st December 2012. Settlement may be made in cash or by cheque, although a clearance period of five working days is required in the latter case. Overseas buyers are recommended to use PayPal as a medium, for the avoidance of credit card charges. Postal delivery: we are unable to provide insured delivery for overseas purchasers, although there are a number of shipping firms that buyers may choose to commission. -

The Ceramics of KK Broni, a Ghanaian Protégé of Michael

Review of Arts and Humanities June 2020, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 13-24 ISSN: 2334-2927 (Print), 2334-2935 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/rah.v9n1a3 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/rah.v9n1a3 Bridging Worlds in Clay: The Ceramics of K. K. Broni, A Ghanaian protégé of Michael Cardew And Peter Voulkos Kofi Adjei1 Keaton Wynn2 kąrî'kạchä seid’ou1 Abstract Kingsley Kofi Broni was a renowned ceramist with extensive exposure and experience in studio art practice. He was one of the most experienced and influential figures in ceramic studio art in Africa. Broni was trained by the famous Michael Cardew at Abuja, Nigeria, Peter Voulkos in the United States, and David Leach, the son of Bernard Leach, in England. Broni had the experience of meeting Bernard Leach while in England and attended exhibitions of Modern ceramists such as Hans Coper. His extensive education, talent, and hard work, coupled with his diverse cultural exposure, make him one of Africa‘s most accomplished ceramists of the postcolonial era. He is credited with numerous national and international awards. He taught for 28 years in the premiere College of Art in Ghana, at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi. Broni has had an extensive exhibition record and has a large body of work in his private collection. This study seeks to unearth and document the contribution of the artist Kingsley Kofi Broni and position him within the broader development of ceramic studio art in Ghana, revealing the significance of his work within the history of Modern ceramics internationally. -

New Zealand Potter Volume 2 Number 2 December 1959

NEW ZEALAND POTTER This issue is published at Wellington by the Editorial Committee of the New Zealand Potter: Doreen Blumhardt, layout and drawings; Terry Barrow, Lee Thomson, advertising; Helen Mason, editor, 29 Everest Street, Khandallah, Wellington. Extra copies may be obtained from the Editor, cost two shillings and Sixpence, Volume Two Number Two December 1959 What stage have we New Zealanders reached with our pottery ? Let's look at the facts. Most of us have got wherever we are by trial and error, not training. There are very few properly trained teachers of the craft, very few professional potters. 4‘ A The rest of us are amateurs who can therefore afford to experiment, but who, according to our critics, have not yet learned to think for ourselves. Available without Charge CONDITION OF LOAN On the credit side we have unbounded enthusiasm and A fine of 2/6 is payable if this a camraderie, as evidenced by the small Napier book is not returned or renewed by the latest date shown on Group, which was able to take the New Zealand Transaction Card. A fine of Exhibition, cope with the tremendous amount of work (id is payable if the Trans- action Card is missing from entailed, and run it successfully. We also have a this pocket. keen market for our pots -= so much so that it can be a TO RENEW—— temptation to lower our standards. But biggest Ring 60—545 (not week—ends) and ask for “Renewals.” asset of all is our own country in which we can find everything we need; not only for raw materials but THE SOUVENIR in New Zealanilivgsthe for inspiration. -

2011 Gallery Catalogue

A SELLING EXHIBITION OF EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY SLIPWARES Long Room Gallery Winchcombe 12th to 26th November 2011 JOHN EDGELER & ROGER LITTLE PRESENT A SELLING EXHIBITION OF EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY SLIPWARES FROM THE WINCHCOMBE AND ST IVES POTTERIES 12th to 26th November 2011, 9.30am to 5.00pm Monday to Saturday (from midday on first day) Long Room Gallery, Queen Anne House, High Street, Winchcombe, Gloucestershire, GL54 5LJ Telephone: 01242 602319 Website: www.cotswoldsliving.co.uk Show terms and conditions Condition: Due to their low fired nature, slipwares are prone to chipping and flaking, and all the pots for sale were originally wood fired in traditional bottle or round kilns, with all the faults and delightful imperfections entailed. We have endeavoured to be as accurate as possible in our descriptions, and comment is made on condition where this is materially more than the normal wear and tear of 80 to 100 years. For the avoidance of any doubt, purchasers are recommended to inspect pots in person. Payment: Payment must be made in full on purchase, and pots will normally be available for collection at the close of the show, in this case on Saturday 26th November 2010. Settlement may be made in cash or by cheque, lthough a clearance period of five working days is required in the latter case. Overseas buyers are recommended to use PayPal as a medium, for the avoidance of credit card charges. Postal delivery: we are unable to provide insured delivery for overseas purchasers, although there are a number of shipping firms that buyers may choose to commission. -

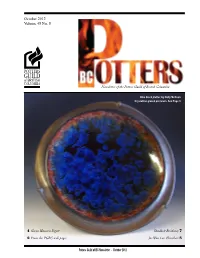

October 2012 Volume 48 No. 8

October 2012 Volume 48 No. 8 Newsletter of the Potters Guild of British Columbia Blue black platter, by Holly McKeen. Crystalline glazed porcelain. See Page 9. 4 Gwyn Hanssen Pigott Shadbolt Residency 7 6 From the PGBC web pages Jae Won Lee: Elsewhere 8 Potters Guild of BC Newsletter . October 2012 1 2012 Gallery Exhibitions October 4 to 29: November 1 to 27: Mug Shots Members of the Potters Collaboration of Vision Guild of BC. Opening Reception: Thursday, Wood-fired ceramics by Jinny Whitehead, Oct. 4, 5 to 7 p.m. Pia Sillem, Jan Lovewell and Ron Robb. Opening Reception: Thursday, Nov. 1, Gallery of BC 5 to 7 p.m. Ceramics www.galleryofbcceramics.com Representing the best of BC Ceramics Follow us on Facebook Gallery Manager Brenda Beaudoin [email protected] 604.669.3606 Gallery Hours as of May 1: 10:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Gallery Assistants Carito Ho, Sasha Krieger, Samantha Knopp, Amanda Sittrop [email protected] Exhibition Committee: Jinny Whitehead, Sheila Morissette, Maggie Kneer, Denise Jeffrey, Celia & Keith Rice-Jones The Gallery of BC Ceramics is a gallery by potters for potters. Looking for that perfect mug? You're sure to find it at the Gallery's Mug Shots exhibition The Gallery coordinates and curates Oct. 4 to 29. Come out and see for yourself the huge range of mug forms that fellow PGBC several exhibitions a year. members have created! Every month we showcase an artist, usually someone just starting his or her career. Gallery Deadlines Gallery Retail juries For more specific information on either We also sell the work of more Tentative dates for drop off of new work jury, please refer to the Guild website www. -

Cape Cod Clay Voice

www.capecodpotters.org July 2004 Cape Cod Potters, Inc. Cape Cod Clay Voice Soup Bowls for Hunger Soup Bowls 2004 was the best year yet. We raised and donated to the Family Pantry a total of $11,240. Special points of The Cape Cod Regional Technical High School did a great job with the soup, service, and the use of the interest: facilities. Cape Cod Five Cents Savings Bank Charita- ble Foundations Trust underwrote any expenses. • Soup Bowls for hunger Dennis Public Market and Peterson's Market donated raises $11,240. the BEEF for the soup. Flowers were donated by Kevin's Petal Cart Flowers and Flora D'Elegance, • Phil Rogers Workshop Cape Cod Paper donated the bags/placemats and Winkir Printing provided printing services. We are • Dan Finnegan October especially grateful for help with setting up, resetting, Workshop and take-down to Senior Girl Scout Troop 847 and the Nauset Regional High School Interact Club. • 2004 Potters Brochure information Many thanks go to the potters, both professionals and students who make the bowls for this event and • Items of interest who also help make the evening a reality. • A new logo ? If you need a form for tax purposes listing the number of bowls that you donated, please send your request to Cape Cod Potters, attention Soup Bowls for Hunger, at Box 76, Chatham, MA 02633-0076. Inside this issue: Potters Brochure 2 Reminders Annual Seconds Sale Items for sale or less 2 The Executive board wishes to remind our members; This event will take place on Sunday October 17th, 2004 from 10am-12noon at Eden Gallery, Route 6A, Looking for a logo 2 Membership applications are mailed out in Decem- Dennis (across from Scargo Lake). -

THE LEACH POTTERY: ONE CENTURY Dates: 17Th

THE LEACH POTTERY: ONE CENTURY Dates: 17th Jan - 14th March 2020 Private View: Friday 17th Jan / 5-7pm Oxford Ceramics opens its 2020 season by celebrating the centenary of one of the most significant ceramic studios of the modern era: the Leach Pottery, founded in 1920. This pottery has shaped studio ceramics as we know it today, and is a cornerstone of ceramic history. It includes over 200 works sourced from across the globe from these masters of ceramics: Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada, Michael Cardew, Kawai Kanjiro, and Tomimoto Kenkichi; as well as antique English slipware from as far back as the 18th century. This is a show that weaves together both influence and the finished article. There is something for the collector, ceramic enthusiasts and the plain curious. “As far back as one goes in time, the works of humanity from prehistoric times have reached us not through stone which crumbles and wears away, or through metal which oxidizes and becomes like powder, but through slabs of pottery, the writing on which is as clear today as it was under the stiletto of the scribe who traced it.” (Bernard Leach, A Potter's Book) James Fordham, the creative director of Oxford Ceramics, says, “This was always going to be a significant show for the gallery, as the Leach Pottery is one of the most respected and influential potteries in the world. I wanted to mark this anniversary with a show that explored not only the work of Leach & Hamada, but that looked deeper into the influences on their work.” Many great potters studied under Leach and many more were inspired by his written work, including A Potter’s Book, published in 1940. -

Michael Cardew, Studio Potter: Papers, 1903-2000

V&A Archive of Art and Design Michael Cardew, studio potter: papers, 1903-2000 Introduction and summary description Creator: Michael Cardew Reference: AAD/2006/2 Extent: 58 files Context Michael Cardew (1901-1983) was a pioneer of the studio pottery movement, and is widely credited as having revived the slipware tradition in England. He held a major international reputation and his work has been highly influential throughout the world. Cardew had a long and rich working life, which included lengthy spells in Africa in addition to the time spent running potteries in Gloucestershire and Cornwall, writing extensively and giving lectures and demonstrations at home and abroad. From 1923-1926 Michael Cardew worked at the St. Ives Pottery, leaving to set up his own pottery at Wincombe from 1926-1939. Cardew finally settled at Wenford Bridge Pottery and worked on and off here until his death on 11 February, 1983. His passion for pottery lead him to teach at Achimota College, Ghana from 1942-45, set up a pottery at Vume from 1946-48 and to be Pottery Officer in Abuja, Nigeria from 1950-1965, where he encouraged such potters as Ladi Kwali. In 1965 he was appointed MBE and in 1981 appointed CBE and chosen as selector and writer for the Crafts Council exhibition 'The Makers Eye'. He also received an honorary doctorate from the Royal College of Art in 1982. Michael Cardew's book, 'Pioneer Pottery' was published in 1969, a film of his life, 'Mud and Water Man' was released in 1973 and his autobiography, 'A Pioneer Potter' was published posthumously in 1988.