Documenting the 2006 New Orleans Mayoral Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mayor Landrieu and Race Relations in New Orleans, 1960-1974

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of New Orleans University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-20-2011 Phases of a Man Called 'Moon': Mayor Landrieu and Race Relations in New Orleans, 1960-1974 Frank L. Straughan Jr. University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Straughan, Frank L. Jr., "Phases of a Man Called 'Moon': Mayor Landrieu and Race Relations in New Orleans, 1960-1974" (2011). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1347. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1347 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Phases of a Man Called ―Moon‖: Mayor Landrieu and Race Relations in New Orleans, 1960-1974 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Frank L. -

The United States Conference of Mayors 85Th Annual Meeting June 23-26, 2017 the Fontainebleau Hotel Miami Beach, Florida

The United States Conference of Mayors 85th Annual Meeting June 23-26, 2017 The Fontainebleau Hotel Miami Beach, Florida DRAFT AGENDA June 14, 2017 KEY INFORMATION FOR ATTENDEES Participation Unless otherwise noted, all plenary sessions, committee meetings, task force meetings, workshops and social events are open to all mayors and other officially-registered attendees. Media Coverage While the plenary sessions, committee meetings, task force meetings and workshops are all open to press registrants, please note all social/evening events are CLOSED to press registrants wishing to cover the meeting for their news agency. Resolution and Committee Deadline The deadline for submission of proposed resolutions by member mayors is May 24, 2017 at 5:00 pm EDT. This is the same deadline for standing committee membership changes. Members can submit resolutions and update committee memberships through our USCM Community web site at community.usmayors.org. Voting Only member mayors of a standing committee are eligible to vote on resolutions before that standing committee. Mayors who wish to record a no vote in a standing committee or the business session should do so within the mobile app. Title Sponsor: #uscm2017 1 Charging Stations Philips is pleased to provide charging stations for electronic devices during the 85th Annual Meeting in Miami Beach. The charging stations are located in the Philips Lounge, within the meeting registration area. Mobile App Download the official mobile app to view the agenda, proposed resolutions, attending mayors and more. You can find it at usmayors.org/app. Available on the App Store and Google Play. Title Sponsor: #uscm2017 2 FONTAINEBLEAU FLOOR PLAN Title Sponsor: #uscm2017 3 NOTICES (Official functions and conference services are located in the Fontainebleau Hotel, unless otherwise noted. -

A City Could Wipe Away 55,000 Old Warrants 1

A City Could Wipe Away 55,000 Old Warrants - Route Fifty Page 1 of 7 SPONSOR CONTENTSEARCH SPONSOR CONTENT Connecting state and local government leaders In The One State That A City Could Wipe A State Braces For In Most States, Child Vegas Sets The Stage Optimizing The Tested The Census, Away 55,000 Old Major Transportation Marriage Is Legal. For Smart City Success Caseworker Concerns About Warrants Funding Cuts As Ballot Some Legislators Are Reaching Hard-To- Measure Nears Trying To Change That Count Residents Passage A City Could Wipe Away 55,000 Old Warrants The New Orleans City Council last month passed a resolution calling for the dismissal of over 55,000 outstanding municipal and traffic warrants, along with their associated fines and fees. The oldest are two decades old. SHUTTERSTOCK By Emma Coleman | NOVEMBER 11, 2019 03:50 PM ET More than 44,000 people in New Orleans have warrants for traffic Most Popular violations and what advocates call “crimes of poverty.” City leaders The New First Responder Crisis: say the system needs to be overhauled. 1 Not Enough Dispatchers FINES AND FEES CRIMINAL JUSTICE NEW ORLEANS In the One State that Tested the 2 Census, Concerns About Reaching Hard-to-Count Residents In Most States, Child Marriage is One in seven adults in New Orleans have a warrant out for their arrest for 3 Legal. Some Legislators Are Trying to Change That a traffic or municipal violation. In many cases, the warrants are for unpaid traffic fines or minor offenses like public drunkenness or disturbing the peace. -

He an T Ic Le

June/July 2018 From The Dean . “Today is the beginning. Today is the first day of what’s next – the first day of a new era for our city. A city open to all. A city that embraces everyone, and gives every one of her children a chance.... You don’t quit on your families, and we - we are not going to quit on you. We are going to embrace all families, regardless of what that family looks like. We talk about how much we love our city. We talk about it. But I am calling upon each one of you, on every New Orleanian … to speak out — and show the same love for the people of our city.” -Mayor LaToya Cantrell May 7, 2018 The Church exists to be a beacon of God’s love for humanity, and a safe place for all people to come and seek this love. The Feast of Pentecost, which comes 50 days after Easter, commemorates the outpouring of the Holy Spirit upon the followers of the Way of Jesus. At this moment they were, and by extension we are, sent into the World to make disciples and claim the gifts that the Holy Spirit has bestowed upon each of us. We are called to work with all people to build the beloved community in the places where we live and move and have our being. For many of the members of Christ Church Cathedral that place is the City of New Orleans. One of my first official responsibilities upon becoming Dean was to represent Bishop Charles Jenkins at the inauguration of Mayor Ray Nagin in the Superdome in May of 2002. -

HEARING AIDS I DON’T WEAR a HEARING AID? Missing Certain Sounds That Stimulate the Brain

“THE PEOPLE’S PAPER” VOL. 20 ISSUE 10 ~ July 2020 [email protected] Online: www.alabamagazette.com 16 Pages – 2 Sections ©2020 Montgomery, Autauga, Elmore, Crenshaw, Tallapoosa, Pike and Surrounding Counties 334-356-6700 Source: www.laserfiche.com Land That I Love: Restoring Our Christian Heritage An excerpt from Land That I Love by Bobbie Ames . “The story of the Declaration is a part of the story of a national legacy, but to understand it, it is necessary to understand as well its makers, the world they lived in, the conditions which produced them, the confidence which encouraged them, the indignities which humiliated them, the obstacles which confronted them, the ingenuity which helped them, the faith which sustained them, the victory which came to them. It is, in other words, a part, a very signal part of a civilization and a period, from which, unlike his Britannic Majesty, it makes no claim to separation. On the contrary, unsurpassed as it is, it takes its rightful place in the literature of democracy. For its primacy, is a primacy which derives from the experience which evoked it. It is imperishable because that experience is remembered.” See page 3B for the complete article and for the link to order your own copy of Land That I Love: Restoring Our Christian Heritage. Rotary Clubs Continue to Serve Primary Montgomery Sunrise Rotary Club hosts Runoff “kitchen shower” for the Salvation Army. July 14th See story on page 8A. Tom Mann, Lt. Farrington, LEASE OTE Ell White II and Neal Hughs P V ! were excited to receive items donated to the Salvation Army by For more information on the elections: the Montgomery Rotary Club. -

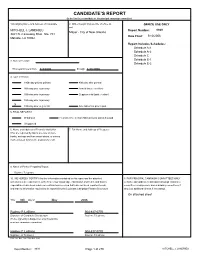

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU Report Number: 9939 Mayor - City of New Orleans 3421 N. Casueway Blvd. Ste. 701 Date Filed: 5/10/2006 Metairie, LA 70002 Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule C 3. Date of Election Schedule E-1 Schedule E-2 This report covers from 4/3/2006 through 4/30/2006 4. Type of Report: 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) 10th day prior to primary X 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more banks, savings and loan associations, or money market mutual fund as the depository of all 9. Name of Person Preparing Report Daytime Telephone 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. Name and address of principal campaign committee, expenditures have been made nor contributions received that have not been reported herein, committee’s chairperson, and subsidiary committees, if and that no information required to be reported by the Louisiana Campaign Finance Disclosure any (use additional sheets if necessary). -

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well DESIREE CHARBONNET Report Number: 70458 Mayor 3860 Virgil Blvd. Orleans Date Filed: 4/30/2018 New Orleans, LA 70122 City of New Orleans Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule A-3 Schedule B 3. Date of Primary 10/14/2017 Schedule E-1 This report covers from 10/30/2017 through 12/18/2017 4. Type of Report: X 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) 10th day prior to primary 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more CYNTHIA C BERNARD banks, savings and loan associations, or money 1650 Kabel Drive market mutual fund as the depository of all New Orleans, LA 70131 REGIONS BANK 400 Poydras St. New Orleans, LA 70130 9. Name of Person Preparing Report PHILIP W REBOWE, CPA Daytime Telephone 504-236-0004 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. -

Chapter 3: the Context: Previous Planning and the Charter Amendment

Volume 3 chapter 3 THE CONTEXT: PREVIOUS PLANNING AND THE CHARTER AMENDMENT his 2009–2030 New Orleans Plan for the 21st Century builds on a strong foundation of previous planning and a new commitment to strong linkage between planning and land use decision making. City Planning Commission initiatives in the 1990s, the pre-Hurricane Katrina years, and the neighborhood-based recovery plans created after Hurricane Katrina inform this long-term Tplan. Moreover, the City entered a new era in November 2008 when voters approved an amendment to the City Charter that strengthened the relationship between the city’s master plan, the comprehensive zoning ordinance and the city’s capital improvement plan, and mandated creation of a system for neighborhood participation in land use and development decision-making—popularly described as giving planning “the force of law.” A Planning Districts For planning purposes, the City began using a map in 1970 designating the boundaries and names of 73 neighborhoods. When creating the 1999 Land Use Plan, the CPC decided to group those 73 neighborhoods into 13 planning districts, using census tract or census block group boundaries for statistical purposes. In the post-Hurricane Katrina era, the planning districts continue to be useful, while the neighborhood identity designations, though still found in many publications, are often contested by residents. This MAP 3.1: PLANNING DISTRICTS Lake No 2 Lake Pontchartrain 10 Michou d Canal Municipal Yacht Harbor 9 6 5 Intracoastal W aterway Mississippi River G ulf O utlet 11 Bayou Bienvenue 7 l 4 bor r Cana Ha l a v nner Na I 8 11 10 1b 9 6 1a Planning Districts ¯ 0 0.9 1.8 3.6 0.45 2.7 Miles 3 2 12 13 Mississippi River master plan uses the 13 planning districts as delineated by the CPC. -

Urban Public Space, Privatization, and Protest in Louis Armstrong Park and the Treme, New Orleans

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2001 Protecting 'Place' in African -American Neighborhoods: Urban Public Space, Privatization, and Protest in Louis Armstrong Park and the Treme, New Orleans. Michael Eugene Crutcher Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Crutcher, Michael Eugene Jr, "Protecting 'Place' in African -American Neighborhoods: Urban Public Space, Privatization, and Protest in Louis Armstrong Park and the Treme, New Orleans." (2001). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 272. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/272 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Housing Desegregation in the Era of Deregulation Christopher Bonastia

Housing Desegregation in the Era of Deregulation Christopher Bonastia hen Jimmy Carter was sworn into the nation’s highest office on January 20, 1977, Civil Rights supporters mustered some hope. In “The State of Black WAmerica—1977,” the Urban League reflected this tempered optimism: After eight years of a national Administration that blacks—rightly or wrongly—regarded as hostile to their needs and aspirations, they now feel that 1977 might bring a change in direction and that possibly the same type of moral leadership that led the nation to accept the legiti- macy of black demands for equality during the 60s, might once again be present in Washington.1 While 94 percent of Black voters supported Carter, the intensity with which the administration would address issues of racial inequality was unclear. As Hugh Davis Graham notes, Carter “stepped into a policy stream that since the late 1960s had carried two conflicting currents”: the “white backlash” politics ex- emplified by Nixon’s “Southern strategy,” and “the quiet mobilization of a com- prehensive regime of civil rights regulation. By the mid-1970s, the expanded civil rights coalition, under the adept coordination of the Leadership Confer- ence on Civil Rights, had won bipartisan respect in Congress for its ability to mobilize constituency group support.” However, Civil Rights gains tended to come in “complex areas little understood by the general public, such as employee testing and minority hiring tables,” rather than in high-profile issues such as housing desegregation.2 While housing had ranked high on Carter’s list of legislative priorities, his focus was on bolstering construction, home ownership, public housing, and rent subsidies rather than fair-housing issues.3 Ironically, fair-housing proponents would have been pleased if HUD’s commitment to desegregation under Carter Christopher Bonastia is a professor of sociology at Lehman College and the City University of New York Graduate Center and the associate director of honors programs at Lehman College. -

January 19, 2021 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi the Honorable Mitch

January 19, 2021 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Mitch McConnell Speaker Majority Leader United States House of Representatives United States Senate Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 The Honorable Kevin McCarthy The Honorable Charles E. Schumer Republican Leader Democratic Leader United States House of Representatives United States Senate Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Dear Speaker Pelosi, Leader McCarthy, Leader McConnell and Leader Schumer: RE: Urgent Action Needed on President-Elect Biden’s American Rescue Plan On behalf of The United States Conference of Mayors, we urge you to take immediate action on comprehensive coronavirus relief legislation, including providing direct fiscal assistance to all cities, which is long overdue. President-elect Biden’s American Rescue Plan contains such assistance as part of an aggressive strategy to contain the virus, increase access to life-saving vaccines, and create a foundation for sustainable and inclusive recovery. American cities and our essential workers have been serving at the frontlines of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic for nearly a year. We have been charged with executing herculean public health efforts and an unprecedented emergency response. Despite immense fiscal pressure, your local government partners oversaw those efforts, while trying to maintain essential services and increase our internal capacity to provide support for residents and businesses who have been crippled by a tanking economy. And yet, as the economic engines of our country, local governments will be relied upon to lead the long- term economic recovery our nation so desperately needs, even as, with few exceptions, cities have been largely left without direct federal assistance. -

God, Gays, and Voodoo: Voicing Blame After Katrina Jefferson Walker University of Southern Mississippi, [email protected]

Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal Volume 41 Combined Volume 41/42 (2014/2015) Article 4 January 2014 God, Gays, and Voodoo: Voicing Blame after Katrina Jefferson Walker University of Southern Mississippi, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/ctamj Part of the Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Walker, J. (2014/2015). God, Gays, and Voodoo: Voicing Blame after Katrina. Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal, 41/42, 29-48. This General Interest is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Walker: God, Gays, and Voodoo: Voicing Blame after Katrina CTAMJ 2014/2015 29 GENERAL INTEREST ARTICLES God, Gays, and Voodoo: Voicing Blame after Katrina Jefferson Walker Visiting Instructor, Department of Communication Studies University of Southern Mississippi [email protected] Abstract Much of the public discourse following Hurricane Katrina’s devastating impact on Louisiana and much of the Gulf Coast in 2005 focused on placing blame. This paper focuses on those critics who stated that Hurricane Katrina was “God’s punishment” for people’s sins. Through a narrative analysis of texts surrounding Hurricane Katrina, I explicate the ways in which individuals argued about God’s judgment and punishment. I specifically turn my attention to three texts: First, a Repent America press release entitled “Hurricane Katrina Destroys New Orleans Days Before ‘Southern Decadence,’” second, a newsletter released by Rick Scarborough of Vision America, and third, Democratic Mayor of New Orleans, Ray Nagin’s “Chocolate City” Speech.