Introduction: Whence Terror Australis?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE MENTOR 81, January 1994

THE MENTOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION CONTENTS #81 ARTICLES: 27 - 40,000 A.D. AND ALL THAT by Peter Brodie COLUMNISTS: 8 - "NEBULA" by Andrew Darlington 15 - RUSSIAN "FANTASTICA" Part 3 by Andrew Lubenski 31 - THE YANKEE PRIVATEER #18 by Buck Coulson 33 - IN DEPTH #8 by Bill Congreve DEPARTMENTS; 3 - EDITORIAL SLANT by Ron Clarke 40 - THE R&R DEPT - Reader's letters 60 - CURRENT BOOK RELEASES by Ron Clarke FICTION: 4 - PANDORA'S BOX by Andrew Sullivan 13 - AIDE-MEMOIRE by Blair Hunt 23 - A NEW ORDER by Robert Frew Cover Illustration by Steve Carter. Internal Illos: Peggy Ranson p.12, 14, 22, 32, Brin Lantrey p.26 Jozept Szekeres p. 39 Kerrie Hanlon p. 1 Kurt Stone p. 40, 60 THE MENTOR 81, January 1994. ISSN 0727-8462. Edited, printed and published by Ron Clarke. Mail Address: PO Box K940, Haymarket, NSW 2000, Australia. THE MENTOR is published at intervals of roughly three months. It is available for published contribution (Australian fiction [science fiction or fantasy]), poetry, article, or letter of comment on a previous issue. It is not available for subscription, but is available for $5 for a sample issue (posted). Contributions, if over 5 pages, preferred to be on an IBM 51/4" or 31/2" disc (DD or HD) in both ASCII and your word processor file or typed, single or double spaced, preferably a good photocopy (and if you want it returned, please type your name and address) and include an SSAE anyway, for my comments. Contributions are not paid; however they receive a free copy of the issue their contribution is in, and any future issues containing comments on their contribution. -

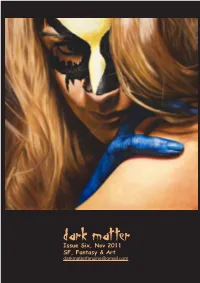

Dark Matter #6

Cover: Wolverine by JKB Fletcher DarkIssue Six, Matter Nov 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Contents: Issue 6 Cover: Wolverine by JKB Fletcher 1 Donations 6 Via Paypal 6 About Dark Matter 7 Competitions 8 Winners 8 Competition terms and conditions 8 Ambassador’s Mission - autographed copy 9 Blood Song - autographed copy 9 Passion - autographed copy 9 The Creature Court Fashion Challenge Contest 10 Christmas Parade 11 Visionary Project 13 Convention/Expo reports 14 Tights and Tiaras: Female Superheroes and Media Cultures 14 #thevenue 14 #thefood 14 #thesessions 15 #karenhealy 15 #fairytaleheroineorfablesuperspy 16 #princecharmingbydaysuperheroinebynight 16 #supermom 16 #wonderwomanworepants 17 #wonderwomanforaday 17 #mywonderwoman 17 #motivationtofight 18 #thefemalesuperhero 19 #dinner 19 #xenaandbuffy 20 #thestakeisnotthepower 20 #buffythetransmediahero 20 #artistandauthors 21 #biggernakedbreasts 22 #sistersaredoingit 22 #sugarandspice 23 #jeangreyasphoenix 23 #nakedmystique 24 #theend 25 Armageddon Expo 2011 26 #thelonegunmen 27 2 Dark Matter #doctorwho 31 #cyberangel 33 #bestlaidplans 33 #theguild 34 #sylvestermccoy 36 #wrapup 37 Timeline Festival 40 MelbourneZombieShuffle 46 White Noise 51 Success without honour 51 New Directions 52 Interviews 54 Troopertrek 2011 54 #update 58 #links 58 Sandeep Parikh and Jeff Lewis @ Armageddon 59 #Effinfunny 60 #5minutecomedyhour 61 #theguild 63 #stanlee 67 #neilgaiman 68 #eringray 69 #zabooandcodex 70 #theguildcomics 72 #thefuture 73 JKB Fletcher talks to Dark Matter -

2256 Inventory 4.Pdf

The Robert Bloch Collection, Acc. ~2256-89-0]-27 Page 11 Box ~ (continueo) Periooicals (continueol: F~ntastic Adyentutes: Vol. 5 (No.8), Allg. 194]: "You Can't Kio Lefty Feep", pp.148-166; "Fairy Tale" under the name Tarleton Fiske, pp.184-202; biographical note on Tarleton Fiske, p.203. Vol. 5 (No.9), Oct. 194]: "A Horse On Lefty Feep", pp. 86-101; "Mystery Of The Creeping Underwear" under the name Tarleton FIske, pp.132-146. Vol. 6 (No.1), Feb. 1944; "Lefty Feep's ~l:abian Nightmare", pp.178-192. Vol. 6 (No. 2), ~pr. 1944: "Lefty Feep Does Time", pp. 156-1'15. Vol. 7 (No.2), Apr. IH5: "Lefty Feep Gets Henpeckeo", 1'1'.116-131. Vol. 6 (No.3), July 1946: "Tree's A Cro"d", pp.74-90. Vol. 9 (No. 51, sept. 1947: "The Mad Scientist", pp. 108-124. Vol. 12 (No.3), Mar. 1950: "Girl From Mars", pp.28-33. Vol. 12 (No.7), July 1950: "End Of YOUl: Rope", 1'p.l10- 124. Vol. 12 (No. S), Aug. 1950: "The Devil With Youl", pp. 8-68. Vol. 13 (No.7), July 1951: "The Dead Don't Die", pp. 8-54; biogl;aphical note, pp.2, 129-130. Fantastic Monsters Of The F11ms, Vol. 1 (No.1), 1962: "Black Lotus", p.10-21, 62. Fantastic Uniyel;se: Vol. 1 (No.6), May 1954: "The Goddess Of Wisdom", pp. 117-128. Vol. 4 (No, 6), Jan. 1956: "You Got To Have Brains", pp .112-120. Vol. 5 (No.6), July 1956: "Founoing Fathel:s", pp.34- Vol. -

THE FOSSIL Official Publication of the Fossils, Inc., Historians Of

THE FOSSIL Official Publication of The Fossils, Inc., Historians of Amateur Journalism Volume 105, Number 3, Whole Number 340, Glenview, Illinois, April 2009 GREETINGS AND FAREWELLS President's Report Guy Miller A letter from Fossil Barry Schrader on a separate matter prompts me to emphasize once again the services of our Library of Amateur Journalism located in the Special Collections Library of the University of Wisconsin in Madison. I have tried to spread the word throughout the hobby from the time I was first elected Fossils President in 1994. Still the fact of its existence seems to have remained a best-kept secret. In my January President's Report, I revealed my need to downsize my hobby office and observed: “Where to send a good portion of the journals is not a problem. I know that my collection of It's a Small World, Campane, The Boxwooder, The Scarlet Cockerel, The Lucky Dog, Churinga, various printed papers, and my ajay books will find their way either into other members' collections or the Library of Amateur Journalism...where...our Fossil collection of amateur journals has found a home.” If you have a collection of ajay journals you deem worthy of preservation, please consider these alternatives. It is satisfying to know that there are fellow ajays still collecting. Already, I have received replies from Barry Schrader and Robert Lichtman, who will be getting their specific requests as soon as the weather permits me to cart the journals to our downtown post office. So, there you area. When you are ready to downsize, remember that there are fellow ajays still collecting and also that we have libraries that are housing special collections. -

SF Commentarycommentary 80A80A

SFSF CommentaryCommentary 80A80A August 2010 SSCCAANNNNEERRSS 11999900––22000022 Doug Barbour Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Bruce Gillespie Paul Ewins Alan Stewart SF Commentary 80A August 2010 118 pages Scanners 1990–2002 Edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia as a supplement to SF Commentary 80, The 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 1, also published in August 2010. Email: [email protected] Available only as a PDF from Bill Burns’s site eFanzines.com. Download from http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC80A.pdf This is an orphan issue, comprising the four ‘Scanners’ columns that were not included in SF Commentary 77, then had to be deleted at the last moment from each of SFCs 78 and 79. Interested readers can find the fifth ‘Scanners’ column, by Colin Steele, in SF Commentary 77 (also downloadable from eFanzines.com). Colin Steele’s column returns in SF Commentary 81. This is the only issue of SF Commentary that will not also be published in a print edition. Those who want print copies of SF Commentary Nos 80, 81 and 82 (the combined 40th Anniversary Edition), should send money ($50, by cheque from Australia or by folding money from overseas), traded fanzines, letters of comment or written or artistic contributions. Thanks to Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) for providing the cover at short notice, as well as his explanatory notes. 2 CONTENTS 5 Ditmar: Dick Jenssen: ‘Alien’: the cover graphic Scanners Books written or edited by the following authors are reviewed by: 7 Bruce Gillespie David Lake :: Macdonald Daly :: Stephen Baxter :: Ian McDonald :: A. -

Land of Bad Dreams

Kyla Lee Ward (b. 1969) is an Australian writer, actor and artist devoted to all things dark and beautiful. Her poetry has previously appeared in Midnight Echo, LAND Bloodsongs, Abaddon, and Gothic.net, as well as in live The of performances. Her novel Prismatic (co-authored as “Edwina Grey”) won the 2007 Aurealis Award for Best AD REAMS Horror Novel. B D Kyla Lee Ward is a darkly shining poetic talent of Australia. The sweep of gothic landscapes and the howling shadowlands of dream in The Land of Bad Dreams propel readers towards old and new vistas of pandemonium, for compulsion is at the heart of Ward’s poetry … compulsion to war against age-old human fears and terrors, and to triumph over them. Who dares fight them with her? In The Land of Bad Dreams, Kyla Ward offers up a rich, eccentric miscellany of dark music, skilfully crafted and strangely wrought. Ann Schwader Delicious antiquity and delirious archaism mix and mingle in Kyla Ward’s verse. With a true poet’s sense of language she teases and tantalises the senses. Leigh Blackmore Kyla has real presence “live” as she has too in these poems. There is a transfixing quality and a warning: “mind how you approach.” Danny Gardner Terror and the beauty it can evoke: that’s what I expect from poetry like this – and that is what The Land of Bad Dreams gave me. This is a collection that should be welcomed. Robert Hood Cover illustration by the Author $18 AU RRP BOOK EXTRACT of KYLA LEE WARD THE LAND OF BAD DREAMS COPYRIGHT NOT FOR SALE, LOAN, COPYING OR PASSING ON IN ANY FORM WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION BY THE PUBLISHER, P’REA PRESS. -

Steam Engine Time 9

Steam Engine Time 9 IN THIS ISSUE: Stephen Campbell Cy Chauvin Ditmar Brad Foster Bruce Gillespie Rob Latham Gillian Polack David Russell Darrell Schweitzer Jan Stinson Frank Weissenborn George Zebrowski and many others DECEMBER 2008 Steam Engine Time Steam Engine Time No 9, December 2008, was edited by Janine Stinson use only, and copyrights belong to the contributors. (tropicsf at earthlink.net), PO Box 248, Eastlake, MI 49626-0248 USA and Bruce Next editorial deadline: 1 January 2009. Gillespie (gandc at pacific.net.au), 5 Howard St., Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia, and published at Illustrations: Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) (front cover, p. 3); Stephen Campbell http://efanzines.com/SFC/SteamEngineTime/SET09.pdf. Members fwa. (back cover); Brad Foster (pp. 59, 60, 62); David Russell (pp. 64, 66, 70, 72, Website: GillespieCochrane.com.au. 73). Print edition only available by negotiation with the editors; first edition and Photographs: Lawrie Brown (pp. 6, 11); Leigh Blackmore (p. 7); Jean Weber primary publication is electronic. A thrice-yearly publishing schedule (at mini- (p. 8); Locus (p. 19); Reeve (p. 37); unknown (p. 40); Foyster collection (p. 50); mum) is intended. All material in this publication was contributed for one-time Alan Stewart (p. 55); Gian Paolo Cossato (pp. 76, 78). Contents 4 EDITORIALS 55 Two ordinary families, with children Jan Stinson Cy Chauvin Fun in Canberra Bruce Gillespie 58 LETTERS OF COMMENT Andrew Darlington :: Steve Sneyd :: E. D. Webber :: Sheryl Birkhead :: TRIBUTES David Lake :: Yvonne Rousseau :: Andy Sawyer :: Fred Lerner :: Cy Chauvin 13 Standing up for science fiction: Stanislaw Lem (1921–2006) :: Paul Voermans :: Lloyd Penney :: Rick Kennett :: Alan Sandercock :: George Zebrowski Robert Elordieta :: Kim Stanley Robinson :: Lyn McConchie :: Darrell 16 Daniel F. -

Nustrnunn W News Volume 7 Number3

Number45 SI.50 nusTRnunn W news Volume 7 Number3 . —-/L^ JUNE |987 IN THIS issue- KEITH TAYLOR WINS 1987 DITMAR APHELION FOLDS TERRY CARR DIES GENE WOLFE SELLS "THE URTH OF THE NEW SUN" TO TOR ARTHUR C. CLARKE SURPRISES US WITH "2061: ODYSSEY THREE" BLUEJAY PUBLISHERS CLOSE CENTURY HUTCHINSON ANNOUNCE SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY SERIES UNWIN HYMAN DROP UNICORN & ORION IMPRINTS PENGUINS LAUNCH CLASSIC SF NEW STAR TREK TV SERIES ON THE WAY PIERS ANTHONY UPDATE JAMES TIPTREE JR DIES NEW BOOKS COMPLETED BY ROBERT HEINLEIN, MARION ZIMMER BRADLEY ANNE MC CAFFREY £ Others PUBLISHERS ANNOUNCEMENTS BOOK REVIEWS CINEMA £ TV NEWS CONVENTIONS & FAN NEWS nUSTRHlimi if HEWS Ml Issue # 45 June 1987 ISSN 0155-8870 Edited and Published by Mervyn R.Binns Phone: (03) 531 5879 'J' ra,^d> Rlpponlea 310Z Victoria, AUSTRALIA All coorespondence to- _ DEAR READERS/ Post Office Box 491 Elsternwlck 3185 I wish to thank all the people who have subscribed Victoria, AUSTRALIA recently, both new and renewals. My old and faith Subscription Rates: ful readers know what to expect, but my new sub scribers are no doubt wondering where ASFN has The current subscription cost is $6.00 for A been over the last six month. Briefly, trying to Issues. This Is an Increase from the last Issue. I have decided to reduce the number of copies eke out a living by listing and selling largely second hand books and more recently putting to for the same amount. When I can publish on some gether the 2nd Issue of BOOKS, which all subscrib sort of a regular basis, I will most likely increase the sub rate and the number of copies ers to ASFN have been sent Incldently, has taken covered. -

THE MENTOR 80, October 1993

THE MENTOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION CONTENTS #80 2 - EDITORIAL SLANT by Ron Clarke 3 - THE JAM JAR by Brent Lillie 5 - THE YANKEE PRIVATEER #17 by Buck Coulson 6 - FROM HUDDERSFIELD TO THE STARS by Steve Sneyd 8 - A SHORT HISTORY OF RUSSIAN "FANTASTIKA" by Andrew Lubenski 17 - A PERSONAL REFERENCE LIBRARY ON A BUDGET by James Verran 18 - JET-ACE LOGAN: The Next Generation by Andrew Darlington 25 - IN DEPTH by Bill Congreve 29 - THE R & R DEPT - Reader's letters 42 - REVIEWS Cover by Antoinette Rydyr Internal Illos: Peggy Ranson p. 4, 28 Kurt Stone p. 29, 42 THE MENTOR 80, October 1993. ISSN 0727-8462. Edited, printed and published by Ron Clarke. NEW POSTAL ADDRESS: THE MENTOR, PO BOX 940K, HAYMARKET, NSW 2000, AUSTRALIA. THE MENTOR is published at intervals of roughly three months. It is available for published contribution (Australian fiction [science fiction or fantasy]), poetry, article, or letter of comment on a previous issue. It is not available for subscription, but is available for $5 for a sample issue (posted). Contributions preferred if over 5 pages to be on an IBM 51/4" or 31/2" disc (DD or HD). Or typed, single or double spaced, preferably a good photocopy (and if you want it returned, please type your name and address) and include an SSAE! so I can make comments on THE MENTOR 80 page 1 submitted works. Contributions are not paid; however they receive a free copy of the issue their contribution is in, and any future issue containing comments on their contribution. -

Australian SF News 46

$150 nusTRnunn NUMBER 46 DECEMBER 1987 IN THIS ISSUE ALFRED BESTER DIES FEATURED BOOK REVIEWS: 'THE SEA AND SUMMER' by GEORGE TURNER Reviewed by RAVERS* GnUERHG Michael Tolly TWO BOOKS BY MICHAEL MOORCOCK Reviewed by Col in Steele RON SMITH DIES ORSON SCOTT CARD REC I EVES ANOTHER HUGO FOR ’SPEAKER FOR THE DEAD- CONSPIRACY WORLD CON REPORTS. HOLLAND WINS '90 A LETTER FROM BRIAN ALDISS A SEQUEL TO ’RENDEZVOUS WITH RAMA' ANNOUNCED COMPREHENSIVE LIST OF PUBLISHER'S ANNOUNCEMENTS KEITH TAYLOR Photo Steve Roylance nusTRnunn news 46 Vol 7 #4 December 1987 ISSN 0155-8870 Edited and published SUBSCRIPTION RATES by Mervyn R.Binns The current rate is still $6.00 for 4 issues, 1 Glen Ei ra Rd and if I decide to change the size or frequency Ripponlea, Victoria 3182 AUSTRALIA in future, current subscriptions will be adjust Please send all correspondence to: ed. All payments should be made to me direct or P.O.Box 491, Elsternwick 3185 to MERV BINNS BOOKS. I have no overseas agents Victoria, AUSTRALIA Phone(03) 531 5879 at this time. Overseas subscribers can send books in trade, or notes If in USA or Britain, ADVERTISING Rates will be quoted on request. although I do not really advise that, or I can It is a waste of space listing them. To be organise payment to friends over there, which quite honest I was a bit disappointed that I will save us the high costs on such a small did not receive any response, even thanks for amount for bank cheques and so forth. -

World Supernatural Literature

World Supernatural Literature Dowling, Terry (Terence William) (1947- ), Australian writer, freelance journalist, award-winning critic, editor and reviewer, one of Australia’s most awarded and highly-regarded writers of speculative fiction. (His fiction has won eleven Ditmar Awards, two Readercon Awards, three Aurealis Awards, a Prix Wolkenstein, and earned two World Fantasy Award nominations). He is author of Rynosseros, Blue Tyson, Twilight Beach and Rynemonn (forthcoming)(the Tom Rynosseros saga), Wormwood, The Man Who Lost Red, Antique Futures: The Best of Terry Dowling; and co-editor of Mortal Fire: Best Australian SF and The Essential Ellison. Dowling has been a musician, songwriter and teacher. He presently teaches a Communications course at the June Dally-Watkins Business Finishing College and is completing a doctorate in Creative Writing which may result in further horror-oriented work. In recent years it has become apparent that despite his acclaimed work as science fiction and fantasy writer having brought him most attention, the supernatural is an integral part of his oeuvre, and is significantly employed by Dowling as one of the modes by which he seeks to resensitise readers to the world about us. Dowling, a writer of formidable intelligence and admirable narrative control, had published many stories with elements of fear and haunting prior to 1995, but An Intimate Knowledge of the Night (Aphelion, 1995) was the first of his works to concentrate almost exclusively on horror. An ambitiously literary work, it presents a series of chilling reality-testings which deal with rapture, fear, the secret, darkest mysteries of the world and the human spirit. -

Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia

SF Commentary 98 50th Anniversary Edition April 2019 84 pages Cover: Elaine Cochrane: ‘Purple Prose’: embroidery. SF COMMENTARY 98 * 50TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION, PART 1 April 2019 84 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 98, 50th ANNIVERSARY EDITION, PART 1, April 2019, is edited and published in a limited number of print copies (this edition only) by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. PREFERRED MEANS OF DISTRIBUTION .PDF FILE FROM EFANZINES.COM: http://efanzines.com or from my email address: [email protected]. FRONT COVER: Elaine Cochrane: ‘Purple Prose’: embroidery presented to Bruce Gillespie on his 72nd birthday. BACK COVER: Ditmar (Dick Jenssen): ‘Follow Me’. ARTWORK: Stephen Campbell (pp. 16, 43, 47); Dimitrii Razuvaev (p. 16); Irene Pagram (pp. 18, 41, 42); Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) (pp. 19, 57); Tim Handfield (p. 43); Grant Gittus (p. 44); Geoff Pollard (p. 44); Cozzolino Hughes (pp. 45, 46); Marius Foley (p. 46); David Wong (p. 47). PHOTOGRAPHS: Randy Byers: ‘Rockaway Sunset’ (p. 3); Gary Mason (p. 4); Christopher Priest (p. 8); Gary Hoff (p. 10); Elaine Cochrane (p. 10); Richard Wilhelm (p. 20); Andrew Darlington (pp. 24–9); Kathy Sauber, University of Washington (pp. 30). 3 CAROUSEL DAYS 32 Tribute to Milt Stevens Alex Skovron John Hertz 33 Tribute to Fred Patten 4 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS: John Hertz WHAT’S A FEW DECADES BETWEEN 36 Tributes to June Moffatt FRIENDS? John Hertz 36 Tribute to Derek Kew Bruce Gillespie Bruce Gillespie 5 In search of personal journalism: 37 Tributes to Mervyn Barrett Gillian Polack interviews Bruce Gillespie Bruce Gillespie, Tom Cardy, Nigel Rowe 7 Bruce Gillespie and Brian Aldiss, 1992: 38 POETRY CORNER Thanks for the thank-you note 38 An Aussie poem, or, I Tim therefore I Tam 9 The early years: Yesterday’s heroes Tim Train 12 The early years: 39 Quoth the raven, ‘Steve Waugh!’ Straight talk about science fiction Tim Train 15 The early years: Hand-made magazines 39 Eight science fiction haiku 17 SFC: The following 40 years ..