Steam Engine Time 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Annual Report

The Annual Report clarion west writers workshop • 2019 Our Mission We support emerging and underrepresented voices by providing writers with world-class instruction to empower their creation of wild and amazing worlds. Through conversation and public engagement, we bring those voices to an ever-expanding community. I continue to be inspired by the Clarion no small part due to the dedication of our Executive West community — in Seattle and staff. In 2019, we said goodbye to Neile beyond. Over the past two years we’ve Graham, who has retired as our Workshop Director's been forced to say goodbye to some dear Director, but promises not to go too far. friends and are joining forces to help For 19 years, Neile has helped to ensure Message others through difficult times. The drain that our classes and workshops are high on our community has been telling. quality as well as warm and welcoming. But the way that everyone has come Her constant guiding light is going to together to support each other in love be missed. Taking over from her is Jae and loss is even more telling. Clarion Steinbacher, who has been training with West is surrounded by a caring family of Neile for the past two years and is already individuals with a shared passion. an integral part of the organization, with Perhaps sometimes it seems that their attention to detail and commitment telling stories, especially speculative to the success of the workshop. Please join fiction stories, is not as important as me in welcoming Jae to their new position, the work of other organizations and as well as welcoming several more of individuals during difficult times. -

Dec. 2006 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE

PO Box 656, Washington, DC 20044 - (202) 232-3141 - Issue #201 - Dec. 2006 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: http://www.lambdasf.org/ New Year’s Eve Reminder: Annual LSF Dec. 2006 - Feb. 2007 Video Party Book Exchange Battlestar Galactica Parties announced by Set for Jan. 14th Meeting from Peter Knapp Peter Knapp Come celebrate New Year’s Eve (and other with Lambda Sci-Fi at Rob and Peter’s stuff, too!) home in DC. This annual event will give us a chance to both recover from the That’s right, gang, the Holiday hectic “holiday” season and to party Season is almost upon us again; and it’s some more in anticipation of the new time for a short reminder about Lambda year. Here are the details on how to join Sci-Fi’s upcoming seventeenth annual in on the fun! book (et al) exchange, which will occur at Where: The home of Rob & the January 14th meeting! All LSF mem- Rob and I will be hosting par- Peter - 1425 “S” Street, NW Washington, bers are invited to participate in this “blind ties to view the next four episodes of DC. For directions, see: exchange” -- and visitors are invited to Battlestar Galactica and Jonathan will http://www.lambdasf.org/lsf/club/ join in the fun, too! be the host for the following four epi- PeterRob.html Briefly, this will be an opportu- sodes. Because the holiday season is Date: Sunday, Dec. 31, 2006 nity for LSFers to exchange copies of their upon us, the Sci Fi Channel will be not be Time: The doors will open at favorite science-fiction, fantasy, or hor- broadcasting the show some weekends. -

The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree on April 26, 2009, the James Tiptree, Jr

Spring/Summer 2009 Volume 5 The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Filter House Co-Winner of the Tiptree H Filter House Wins the Tiptree On April 26, 2009, The James Tiptree, Jr. H New Essay Collection from Literary Award Council announced that the Ursula K. Le Guin 2008 Tiptree Award will be going to Patrick Special Features Ness’s young adult novel The Knife of Never Letting Go and Nisi Shawl’s Filter House, an H Hanging out along the Aqueduct…, by Nisi Shawl Aqueduct Press book. page 9 The Tiptree Award, an annual literary prize H L. Timmel Duchamp for science fiction or fantasy “that expands or Interviews Liz Henry about explores our understanding of gender,” will The WisCon Chronicles, Vol. 3 be presented on Memorial Day weekend at page 6 WisCon in Madison, Wisconsin. Each winner H Gwyneth Jones writes about will receive $1000 in prize money, an original The Buonarotti Quartet artwork created specifically for the winning page 2 novel or story, and a confection, usually choco- H Three Observations and a late. The 2008 jurors were Gavin J. Grant Dialogue by Sylvia Kelso page 2 (chair), K. Tempest Bradford, Leslie Howle, Roz Kaveney, and Catherynne M. Valente. In Other News The award is named for Alice B. Sheldon, who wrote under the pseudonym H Aqueduct Celebrates James Tiptree, Jr. By her impulsive choice of a masculine pen name, Sheldon 5th Anniversary cont. on page 5 page 8 H New Spring Releases New from Aqueduct: Ursula K. Le Guin, page 12 Cheek by Jowl Talks and Essays about How and Why Fantasy Matters The monstrous homogenization of our world has now almost destroyed the map, any map, by making every place on it exactly like every other place, and leaving no blanks. -

The Evolution of Lisp

1 The Evolution of Lisp Guy L. Steele Jr. Richard P. Gabriel Thinking Machines Corporation Lucid, Inc. 245 First Street 707 Laurel Street Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142 Menlo Park, California 94025 Phone: (617) 234-2860 Phone: (415) 329-8400 FAX: (617) 243-4444 FAX: (415) 329-8480 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Lisp is the world’s greatest programming language—or so its proponents think. The structure of Lisp makes it easy to extend the language or even to implement entirely new dialects without starting from scratch. Overall, the evolution of Lisp has been guided more by institutional rivalry, one-upsmanship, and the glee born of technical cleverness that is characteristic of the “hacker culture” than by sober assessments of technical requirements. Nevertheless this process has eventually produced both an industrial- strength programming language, messy but powerful, and a technically pure dialect, small but powerful, that is suitable for use by programming-language theoreticians. We pick up where McCarthy’s paper in the first HOPL conference left off. We trace the development chronologically from the era of the PDP-6, through the heyday of Interlisp and MacLisp, past the ascension and decline of special purpose Lisp machines, to the present era of standardization activities. We then examine the technical evolution of a few representative language features, including both some notable successes and some notable failures, that illuminate design issues that distinguish Lisp from other programming languages. We also discuss the use of Lisp as a laboratory for designing other programming languages. We conclude with some reflections on the forces that have driven the evolution of Lisp. -

THE MENTOR 81, January 1994

THE MENTOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION CONTENTS #81 ARTICLES: 27 - 40,000 A.D. AND ALL THAT by Peter Brodie COLUMNISTS: 8 - "NEBULA" by Andrew Darlington 15 - RUSSIAN "FANTASTICA" Part 3 by Andrew Lubenski 31 - THE YANKEE PRIVATEER #18 by Buck Coulson 33 - IN DEPTH #8 by Bill Congreve DEPARTMENTS; 3 - EDITORIAL SLANT by Ron Clarke 40 - THE R&R DEPT - Reader's letters 60 - CURRENT BOOK RELEASES by Ron Clarke FICTION: 4 - PANDORA'S BOX by Andrew Sullivan 13 - AIDE-MEMOIRE by Blair Hunt 23 - A NEW ORDER by Robert Frew Cover Illustration by Steve Carter. Internal Illos: Peggy Ranson p.12, 14, 22, 32, Brin Lantrey p.26 Jozept Szekeres p. 39 Kerrie Hanlon p. 1 Kurt Stone p. 40, 60 THE MENTOR 81, January 1994. ISSN 0727-8462. Edited, printed and published by Ron Clarke. Mail Address: PO Box K940, Haymarket, NSW 2000, Australia. THE MENTOR is published at intervals of roughly three months. It is available for published contribution (Australian fiction [science fiction or fantasy]), poetry, article, or letter of comment on a previous issue. It is not available for subscription, but is available for $5 for a sample issue (posted). Contributions, if over 5 pages, preferred to be on an IBM 51/4" or 31/2" disc (DD or HD) in both ASCII and your word processor file or typed, single or double spaced, preferably a good photocopy (and if you want it returned, please type your name and address) and include an SSAE anyway, for my comments. Contributions are not paid; however they receive a free copy of the issue their contribution is in, and any future issues containing comments on their contribution. -

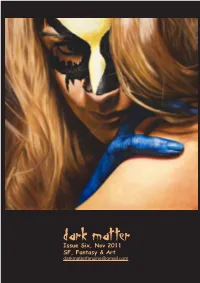

Dark Matter #6

Cover: Wolverine by JKB Fletcher DarkIssue Six, Matter Nov 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Contents: Issue 6 Cover: Wolverine by JKB Fletcher 1 Donations 6 Via Paypal 6 About Dark Matter 7 Competitions 8 Winners 8 Competition terms and conditions 8 Ambassador’s Mission - autographed copy 9 Blood Song - autographed copy 9 Passion - autographed copy 9 The Creature Court Fashion Challenge Contest 10 Christmas Parade 11 Visionary Project 13 Convention/Expo reports 14 Tights and Tiaras: Female Superheroes and Media Cultures 14 #thevenue 14 #thefood 14 #thesessions 15 #karenhealy 15 #fairytaleheroineorfablesuperspy 16 #princecharmingbydaysuperheroinebynight 16 #supermom 16 #wonderwomanworepants 17 #wonderwomanforaday 17 #mywonderwoman 17 #motivationtofight 18 #thefemalesuperhero 19 #dinner 19 #xenaandbuffy 20 #thestakeisnotthepower 20 #buffythetransmediahero 20 #artistandauthors 21 #biggernakedbreasts 22 #sistersaredoingit 22 #sugarandspice 23 #jeangreyasphoenix 23 #nakedmystique 24 #theend 25 Armageddon Expo 2011 26 #thelonegunmen 27 2 Dark Matter #doctorwho 31 #cyberangel 33 #bestlaidplans 33 #theguild 34 #sylvestermccoy 36 #wrapup 37 Timeline Festival 40 MelbourneZombieShuffle 46 White Noise 51 Success without honour 51 New Directions 52 Interviews 54 Troopertrek 2011 54 #update 58 #links 58 Sandeep Parikh and Jeff Lewis @ Armageddon 59 #Effinfunny 60 #5minutecomedyhour 61 #theguild 63 #stanlee 67 #neilgaiman 68 #eringray 69 #zabooandcodex 70 #theguildcomics 72 #thefuture 73 JKB Fletcher talks to Dark Matter -

Remote Debugging and Reflection in Resource Constrained Devices Nikolaos Papoulias

Remote Debugging and Reflection in Resource Constrained Devices Nikolaos Papoulias To cite this version: Nikolaos Papoulias. Remote Debugging and Reflection in Resource Constrained Devices. Program- ming Languages [cs.PL]. Université des Sciences et Technologie de Lille - Lille I, 2013. English. tel-00932796 HAL Id: tel-00932796 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00932796 Submitted on 17 Jan 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N° d’ordre : 41342 THESE présentée en vue d’obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR en Spécialité : informatique par Nikolaos Papoulias DOCTORAT DELIVRE CONJOINTEMENT PAR MINES DOUAI ET L’UNIVERSITE DE LILLE 1 Titre de la thèse : Remote Debugging and Reflection in Resource Constrained Devices Soutenue le 19/12/2013 à 10h devant le jury d’examen : Président Roel WUYTS (Professeur – Université de Leuven) Directeur de thèse Stéphane DUCASSE (Directeur de recherche – INRIA Lille) Rapporteur Marianne HUCHARD (Professeur – Université Montpellier 2) Rapporteur Alain PLANTEC (Maître-Conf-HDR – Université de Bretagne Occ.) Examinateur Serge STINCKWICH (Maître-Conf – Université de Caen) co-Encadrant Noury BOURAQADI (Maître-Assistant – Mines de Douai) co-Encadrant Marcus DENKER (Chargé de recherche – INRIA Lille) co-Encadrant Luc FABRESSE (Maître-Assistant – Mines de Douai) Laboratoire(s) d’accueil : Dépt. -

Science Fiction Review 29 Geis 1979-01

JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1979 NUMBER 29 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $1.50 NOISE LEVEL By John Brunner Interviews: JOHN BRUNNER MICHAEL MOORCOCK HANK STINE Orson Scott Card - Charles Platt - Darrell Schweitzer Elton Elliott - Bill Warren SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC RO. Bex 11408 COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN January, 1979 — Vol .8, No.l Based on a forthcoming novel, SIVA, Portland, OR WHOLE NUMBER 29 by Leigh Richmond 97211 ALIEN TOUTS......................................3 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & piblisher SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION INTERVIEW WITH JOHN BRUWER............. 8 PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY CONDUCTED BY IAN COVELL PAGE 63 JAN., MARCH, MAY, JULY, SEPT., NOV. NOISE LEVEL......................................... 15 SINGLE COPY ---- $1.50 A COLUMN BY JOHN BRUNNER REVIEWS-------------------------------------------- INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL MOORCOCK.. .18 PHOfC: (503) 282-0381 CONDUCTED BY IAN COVELL "seasoning" asimov's (sept-oct)...27 "swanilda 's song" analog (oct)....27 THE REVIEW OF SHORT FICTION........... 27 "LITTLE GOETHE F&SF (NOV)........28 BY ORSON SCOTT CARD MARCHERS OF VALHALLA..............................97 "the wind from a burning WOMAN ...28 SKULL-FACE....................................................97 "hunter's moon" analog (nov).....28 SON OF THE WHITE WOLF........................... 97 OCCASIONALLY TENTIONING "TUNNELS OF THE MINDS GALILEO 10.28 SWORDS OF SHAHRAZAR................................97 SCIENCE FICTION................................ 31 "the incredible living man BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER BLACK CANAAN........................................ -

SF COMMENTARY 81 40Th Anniversary Edition, Part 2

SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 June 2011 IN THIS ISSUE: THE COLIN STEELE SPECIAL COLIN STEELE REVIEWS THE FIELD OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) THE EDITOR PAUL ANDERSON LENNY BAILES DOUG BARBOUR WM BREIDING DAMIEN BRODERICK NED BROOKS HARRY BUERKETT STEPHEN CAMPBELL CY CHAUVIN BRAD FOSTER LEIGH EDMONDS TERRY GREEN JEFF HAMILL STEVE JEFFERY JERRY KAUFMAN PETER KERANS DAVID LAKE PATRICK MCGUIRE MURRAY MOORE JOSEPH NICHOLAS LLOYD PENNEY YVONNE ROUSSEAU GUY SALVIDGE STEVE SNEYD SUE THOMASON GEORGE ZEBROWSKI and many others SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 CONTENTS 3 THIS ISSUE’S COVER 66 PINLIGHTERS Binary exploration Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Stephen Campbell Damien Broderick 5 EDITORIAL Leigh Edmonds I must be talking to my friends Patrick McGuire The Editor Peter Kerans Jerry Kaufman 7 THE COLIN STEELE EDITION Jeff Hamill Harry Buerkett Yvonne Rousseau 7 IN HONOUR OF SIR TERRY Steve Jeffery PRATCHETT Steve Sneyd Lloyd Penney 7 Terry Pratchett: A (disc) world of Cy Chauvin collecting Lenny Bailes Colin Steele Guy Salvidge Terry Green 12 Sir Terry at the Sydney Opera House, Brad Foster 2011 Sue Thomason Colin Steele Paul Anderson Wm Breiding 13 Colin Steele reviews some recent Doug Barbour Pratchett publications George Zebrowski Joseph Nicholas David Lake 16 THE FIELD Ned Brooks Colin Steele Murray Moore Includes: 16 Reference and non-fiction 81 Terry Green reviews A Scanner Darkly 21 Science fiction 40 Horror, dark fantasy, and gothic 51 Fantasy 60 Ghost stories 63 Alternative history 2 SF COMMENTARY No. 81, June 2011, 88 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia. -

Robert Calvert Captain Lockheed and the Starfighters Mp3, Flac, Wma

Robert Calvert Captain Lockheed And The Starfighters mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Non Music Album: Captain Lockheed And The Starfighters Country: US Released: 1977 Style: Alternative Rock, Spoken Word MP3 version RAR size: 1723 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1425 mb WMA version RAR size: 1911 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 657 Other Formats: DXD AHX MP4 FLAC AAC VOC WMA Tracklist Hide Credits Franz Joseph Strauss, Defence Minister, Reviews The Luftwaffe In 1958. Finding It A1 1:40 Somewhat Lacking In Image Potential A2 The Aerospaceage Inferno 4:35 A3 Aircraft Salesman (A Door In The Foot) 1:41 The Widow Maker A4 2:42 Guitar [Lead] – Dave Brock A5 Two Test Pilots Discuss The Starfighter's Performance 0:41 A6 The Right Stuff 4:23 A7 Board Meeting (Seen Through A Contract Lense) 0:58 A8 The Song Of The Gremlin (Part One) 3:21 B1 Ground Crew (Last Minute Reassembly Before Take Off) 3:17 B2 Hero With A Wing 3:20 B3 Ground Control To Pilot 0:52 B4 Ejection 3:35 B5 Interview 3:55 B6 I Resign 0:27 B7 The Song Of The Gremlin (Part Two) 3:10 B8 Bier Garten 0:38 Catch A Falling Starfighter B9 2:54 Percussion [Funeral Drum] – Twink Credits Art Direction – Pierre Tubbs Bass, Guitar [Rhythm] – Lemmy Drums – Simon King Guitar [Lead, Rhythm], Bass – Paul Rudolph Illustration – Stanislaw Fernandes Keyboards – Adrian Wagner Lyrics By – Bob Calvert* Music By – Adrian Wagner (tracks: A8, B7), Arthur Brown (tracks: A8, B7), Dave Brock (tracks: A4), Bob Calvert* (tracks: A1 to A7, A8 to B6, B8, B9) Producer – Roy Baker* Saxophone – Nik Turner Synthesizer – Del Dettmar Vocals – Arthur Brown Vocals, Voice [Spoken Word], Percussion – Robert Calvert Voice [Spoken Word] – Jim Capaldi, Richard Ealing*, Tom Mittledorf, Vivian Stanshall Notes Robert Calvert's 1st solo project. -

Foundation Review of Science Fiction 125 Foundation the International Review of Science Fiction

The InternationalFoundation Review of Science Fiction 125 Foundation The International Review of Science Fiction In this issue: Jacob Huntley and Mark P. Williams guest-edit on the legacy of the New Wave A previously unpublished interview with Michael Moorcock Brian Baker tours Europe with Brian Aldiss Jonathan Barlow conjures with Elric, Jerry Cornelius and Lord Horror Foundation Nick Hubble on the persistence of New Wave-forms in Christopher Priest Peter Higgins is inspired by Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun Gwyneth Jones revisits aliens and the Aleutians 45.3 Volume Conference reports from Kerry Dodd and Gul Dag In addition, there are reviews by: number 125 Jeremy Brett, Kanta Dihal, Carl Freedman, Jennifer Harwood-Smith, Nick Hubble, Carl Kears, Paul Kincaid, Sandor Klapcsik, Chris Pak, Umberto Rossi, Alison Tedman and Juha Virtanen 2016 Of books by: Anne Hiebert Alton and William C. Spruiell, Martyn Amos and Ra Page, Gerry Canavan and Kim Stanley Robinson, Brian Catling, Sonja Fritzsche, Ian McDonald, Paul March-Russell, China Miéville, Carlo Pagetti, Hannu Rajaniemi, Tricia Sullivan and Gene Wolfe Special section on Michael Moorcock and the New Wave Cover image/credit: Mal Dean, cover to the original hardback edition of Michael Moorcock, The Final Programme (Allison & Busby, 1968) Foundation is published three times a year by the Science Fiction Foundation (Registered Charity no. 1041052). It is typeset and printed by The Lavenham Press Ltd., 47 Water Street, Lavenham, Suffolk, CO10 9RD. Foundation is a peer-reviewed journal. Subscription rates for 2017 Individuals (three numbers) United Kingdom £22.00 Europe (inc. Eire) £24.00 Rest of the world £27.50 / $42.00 (U.S.A.) Student discount £15.00 / $23.00 (U.S.A.) Institutions (three numbers) Anywhere £45.00 / $70.00 (U.S.A.) Airmail surcharge £7.50 / $12.00 (U.S.A.) Single issues of Foundation can also be bought for £7.00 / $15.00 (U.S.A.). -

Science Fiction Review 30 Geis 1979-03

MARCH-APRIL 1979 NUMBER 30 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $1.50 Interviews: JOAN D. VINGE STEPHEN R. DONALDSON NORMAN SPINRAD Orson Scott Card - Charles Platt - Darrell Schweitzer Elton Elliott - Bill Warren SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC P.O. Be* 11408 MARCH, 1979 — VOL.8, no.2 Portland, OR 97211 WHOLE NUMBER 30 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & publisher CONFUCIUS SAY MAN WHO PUBLISHES FANZINES ALL LIFE DOOMED TO PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY SEEK MIMEOGRAPH IN HEAVEN, HEKTO- COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN JAN., MARCH, MAY, JULY, SEPT., NOV. Based on "Hellhole" by David Gerrold GRAPH IN HELL (To appear in ASIMOV'S SF MAGAZINE) SINGLE COPY — $1.50 ALIEN THOUGHTS by the editor........... 4 PUOTE: (503) 282-0381 INTERVIEW WITH JOAN D. VINGE CONDUCTED BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER....8 LETTERS---------------- THE VIVISECTOR GEORGE WARREN........... A COLUMN BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER. .. .14 JAMES WILSON............. PATRICIA MATTHEWS. POUL ANDERSON........... YOU GOT NO FRIENDS IN THIS WORLD # 2-8-79 ORSON SCOTT CARD.. A REVIEW OF SHORT FICTION LAST-MINUTE NEWS ABOUT GALAXY BY ORSON SCOTT CARD....................................20 NEAL WILGUS................ DAVID GERROLD........... Hank Stine called a moment ago, to THE AWARDS ARE Ca-IING!I! RICHARD BILYEU.... say that he was just back from New York and conferences with the pub BY ORSON SCOTT CARD....................................24 GEORGE H. SCITHERS ARTHUR TOFTE............. lisher. [That explains why his INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN R. DONALDSON ROBERT BLOCH.............. phone was temporarily disconnected.] The GAIAXY publishing schedule CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS.......................26 JONATHAN BACON.... SAM MOSKOWITZ........... is bi-monthly at the moment, and AND THEN I READ.... DARRELL SCHWEITZER there will be upcoming some special separate anthologies issued in the BOOK REVIEWS BY THE EDITOR..................31 CHARLES PLATT..........