Dissolving Borders: the Integration of Writing Into a Movement Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resources to Support Remote Dance Teaching

Resources to Support Remote Dance Teaching This document includes a number of dance resources and activities that can be completed remotely by students GENERAL RESOURCES: TWINKL resources Twinkl are offering one month ‘ultimate membership’ totally free of charge.T o register, visit https://www.twinkl.co.uk/offer and type in the code - UKTWINKLHELPS. The website includes excellent dance resources created by Justine Reeve AKA ‘The Dance Teacher’s Agony Aunt’. ArtsPool ArtsPool are also offering access to their e-learning portal free of charge for 1 month. This is for GCSE groups only. To gain access, email [email protected] BBC A series of street dance videos that could assist learning techniques at home, or support a research project. There are lots of other resources on BBC Teach and School Radio that could assist home study. Click here for more Resource lists for dancers Created by dance education expert Fiona Smith, this document is free to access on the One Dance UK website. It includes links to a variety of YouTube performances that could help students research different styles, cultures and companies. It also includes links to performances that may have been used for GCSE/BTEC/RSL/A LEVEL study. Click here for more BalletBoyz Access to a range of resources that could be used to accompany home study Click here for more 11 Plus A strength and conditioning programme developed at Elmhurst Ballet School and in collaboration with the University of Wolverhampton Click here for more Quizlet Create your own revision cards Click here for more Discover! Creative Careers Research into careers linked to the creative industries Click here for more Create & Dance The Royal Opera House’s creative learning programme with digital activities Click here for more Marquee TV A subscription-based service for viewing dance and other art forms Click here for more Yoga4Dancers Yoga sequences that can be done at home Click here for more 64 Million Artists Will be sharing two weeks of fun, free and accessible creative challeng-es to do at home starting 23rd March. -

Glen Tetley: Contributions to the Development of Modern

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. GLEN TETLEY: CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN DANCE IN EUROPE 1962-1983 by Alyson R. Brokenshire submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences Of American University In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree Of Masters of Arts In Dance Dr. -

Come up to the Lab a Sciart Special

024 on tourUK DRAMA & DANCE 2004 COME UP TO THE LAB A SCIART SPECIAL BOBBY BAKER_RANDOM DANCE_TOM SAPSFORD_CAROL BROWN_CURIOUS KIRA O’REILLY_THIRD ANGEL_BLAST THEORY_DUCKIE CHEEK BY JOWL_QUARANTINE_WEBPLAY_GREEN GINGER CIRCUS_DIARY DATES_UK FESTIVALS_COMPANY PROFILES On Tour is published bi-annually by the Performing Arts Department of the British Council. It is dedicated to bringing news and information about British drama and dance to an international audience. On Tour features articles written by leading and journalists and practitioners. Comments, questions or feedback should be sent to FEATURES [email protected] on tour 024 EditorJohn Daniel 20 ‘ALL THE WORK I DO IS UNCOMPLETED AND Assistant Editor Cathy Gomez UNFINISHED’ ART 4 Dominic Cavendish talks to Declan TheirSCI methodologies may vary wildly, but and Third Angel, whose future production, Donnellan about his latest production Performing Arts Department broadly speaking scientists and artists are Karoshi, considers the damaging effects that of Othello British Council WHAT DOES LONDON engaged in the same general pursuit: to make technology might have on human biorhythms 10 Spring Gardens SMELL LIKE? sense of the world and of our place within it. (see pages 4-7). London SW1A 2BN Louise Gray sniffs out the latest projects by Curious, In recent years, thanks, in part, to funding T +44 (0)20 7389 3010/3005 Kira O’Reilly and Third Angel Meanwhile, in the world of contemporary E [email protected] initiatives by charities like The Wellcome Trust dance, alongside Wayne McGregor, we cover www.britishcouncil.org/arts and NESTA (the National Endowment for the latest show from Carol Brown, which looks COME UP TO Science, Technology and the Arts), there’s THE LAB beyond the body to virtual reality, and Tom Drama and Dance Unit Staff 24 been a growing trend in the UK to narrow the Lyndsey Winship Sapsford, who’s exploring the effects of Director of Performing Arts THEATRE gap between arts and science professionals John Kieffer asks why UK hypnosis on his dancers (see pages 9-11). -

Dance & Museums Working Together Symposium Report

Dance & Museums Working Together Symposium Symposium Report - Content, Analysis & Recommendations January 2015 Author: Emma McFarland, Consultant, eMc arts E: [email protected] arts eMc TRINITY LABAN CONSERVATOIRE OF MUSIC & DANCE Contents Section 1 : About the Symposium 4 Introduction 4 1. Overview 5 Section 2 : Symposium Content 7 2. Presentations & Case Studies 7 3. Feedback from Discussion Groups 14 4. Enquiry Groups 4.1 Topic 1 – Schools & the Curriculum 14 4.2 Topic 2 – Responding Creatively to Objects 16 4.3 Topic 3 – Audience Engagement and Response 20 4.4 Topic 4 – Dance as Object – Live Curation and Archiving 23 5. Panel Q & A 25 Section 3 : Rationale for Dance and Museums Working Together 28 6. Opportunities and Benefits of Museum – Dance Collaboration 6.1 New and innovative ways of interpreting objects / artefacts, collections 28 and exhibitions 6.2 Developing new audiences / visitors 28 6.3 Collaboration as a way of informing the development of dance performance 29 6.4 Providing rich, new artistic stimuli 29 6.5 Encouraging reflections on dance’s own history 30 6.6 Offers new approaches to museum learning and participatory work 30 6.7 Organisational benefits 30 Section 4 : Considerations around Museums – Dance Collaboration 31 7. Potential Issues and Challenges of Museums – Dance Collaboration 7.1 Need for deeply rooted partnerships 31 7.2 The need for trust....and risk 31 7.3 The role of the artist 32 7.4 Purpose, priorities and planning 33 7.5 Audiences and visitors 33 7.6 Practical considerations 34 7.7 Evaluation of ‘pop-up’ dance activity in museums 34 Section 5 : Where Next? 36 8. -

Rambert Area of Study: Set Work Rooster

Component 2: Rambert Area of Study: Set work Rooster Refer also to Alston booklet/ North resources and Rooster booklet (s) for detail to support this guide. Revision Booklet What AQA need you to know: Understood Revised Revised 2017 2018 the stylistic features of Rambert Dance Company and how these relate to the genre the choreographic approach (the particular technique, movement style and choreographic style) of a minimum of two named practitioners the influences affecting the development of the named practitioner’s technique and style at least two works from each of the selected named practitioners, including the following features of each work: significance of the character of each dance the subject matter (eg theme or topic) and its treatment the form of the dance (eg phrases, sections) the constituent features of the dance and their relevance in embodying the subject matter the importance of the practitioners’ works in the development of the genre in relation to Rambert Dance Company the relationship between the development of the genre and its context, ie the position of the genre within history, culture and society the genre’s capacity to reflect and challenge society terminology specific to the genre Rambert Background Knowledge What was Marie Rambert’s dance background? How would Rambert’s background have affected her style? What was Ballet Rambert’s key focus until 1966? Who brought around change in 1966? What was his role? What changes did he bring about? What roles did Bruce perform as a principal? When was his first piece -

ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’S QOYA: a Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life That Is Wise, Wild and Free

“The Qoya were the sacred women of the Inka, daughters of the Sun, the ones chosen to uplift humanity to our grandest and greatest possibilities. Rochelle accomplishes this great task in this stunning book.” —Alberto Villoldo, PhD, author of Shaman, Healer, Sage and One Spirit Medicine Q YA A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’s QOYA: A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free “Through the sincere, witty, and profound sharing of her own life experiences, Rochelle reveals to us a valuable map to recover one’s joy, confidence, and authenticity. She shows us the way back to love by feeling gratitude for one’s own experiences. She offers us price- less tools and practices to reconnect with our innate intelligence and sense of knowing what is right for us. More than a book, this is a companion through difficult moments or for getting from well to wonderful!” —Marcela Lobos, shamanic healer, senior staff member at the Four Winds Society, and co-founder of Los Cuatro Caminos in Chile “Qoya represents the future – the future of spirituality, femininity, and movement. If I’ve learned anything in my work, it is that there is an awakening of women everywhere. The world is yearning for the balance of the feminine essence. This book shows us how to take the next step.” —Kassidy Brown, co-founder of We Are the XX “Rochelle Schieck has made her life into a solitary vow: to remem- ber who she is – not in thought or theory – but in her bones, in the truth that only exists in her body. -

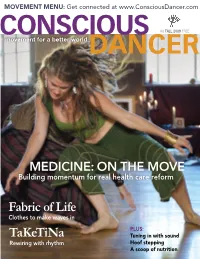

Taketina Tuning in with Sound Rewiring with Rhythm Hoof Stepping a Scoop of Nutrition

MOVEMENT MENU: Get connected at www.ConsciousDancer.com CONSCIOUS #8 FALL 2009 FREE movement for a better world DANCER MEDICINE: ON THE MOVE Building momentum for real health care reform Fabric of Life Clothes to make waves in PLUS: TaKeTiNa Tuning in with sound Rewiring with rhythm Hoof stepping A scoop of nutrition • PLAYING ATTENTION • DANCE–CameRA–ACtion • BREEZY CLEANSING American Dance Therapy Association’s 44th Annual Conference: The Dance of Discovery: Research and Innovation in Dance/Movement Therapy. Portland, Oregon October 8 - 11, 2009 Hilton Portland & Executive Tower www.adta.org For More Information Contact: [email protected] or 410-997-4040 Earn an advanced degree focused on the healing power of movement Lesley University’s Master of Arts in Expressive Therapies with a specialization in Dance Therapy and Mental Health Counseling trains students in the psychotherapeutic use of dance and movement. t Work with diverse populations in a variety of clinical, medical and educational settings t Gain practical experience through field training and internships t Graduate with the Dance Therapist Registered (DTR) credential t Prepare for the Licensed Mental Health Counselor (LMHC) process in Massachusetts t Enjoy the vibrant community in Cambridge, Massachusetts This program meets the educational guidelines set by the American Dance Therapy Association For more information: www.lesley.edu/info/dancetherapy 888.LESLEY.U | [email protected] Let’s wake up the world.SM Expressive Therapies GR09_EXT_PA007 CONSCIOUS DANCER | FALL 2009 1 Reach -

Dancing Into the Chthulucene: Sensuous Ecological Activism In

Dancing into the Chthulucene: Sensuous Ecological Activism in the 21st Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kelly Perl Klein Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Dr. Harmony Bench, Advisor Dr. Ann Cooper Albright Dr. Hannah Kosstrin Dr. Mytheli Sreenivas Copyrighted by Kelly Perl Klein 2019 2 Abstract This dissertation centers sensuous movement-based performance and practice as particularly powerful modes of activism toward sustainability and multi-species justice in the early decades of the 21st century. Proposing a model of “sensuous ecological activism,” the author elucidates the sensual components of feminist philosopher and biologist Donna Haraway’s (2016) concept of the Chthulucene, articulating how sensuous movement performance and practice interpellate Chthonic subjectivities. The dissertation explores the possibilities and limits of performances of vulnerability, experiences of interconnection, practices of sensitization, and embodied practices of radical inclusion as forms of activism in the context of contemporary neoliberal capitalism and competitive individualism. Two theatrical dance works and two communities of practice from India and the US are considered in relationship to neoliberal shifts in global economic policy that began in the late 1970s. The author analyzes the dance work The Dammed (2013) by the Darpana Academy for Performing Arts in Ahmedabad, -

FINAL Thesis Dance, Empowerment and Spirituality

13 Introduction Imagine entering a space full of people, all engaged with their own movement, emotions and process. Some are dancing fast; others are lying on the floor. Some are stretching their bodies tall in all directions, whereas other movements are barely visible. People may be crying, shouting, or dancing with an expression of joy on their face. There are men and women of all ages, colourfully dressed. If you let your fantasy run wild, you can imagine them as animals swishing their tails while moving stealthily through the jungle, as indigenous people, stamping their feet on the beat. You may see dancing fairies, solid trees and stout warriors. You may see vulnerable, delicate beings of great beauty, or even see seaweeds, moving gently on an invisible current. The raw and the ugly, the wild and the contained, the silence and the storm all may be present in the room. Welcome. You have just arrived in a Movement Medicine space. These spaces form the focus of this research project. Indeed, paraphrasing Performance Studies scholar Fiona Buckland, this research is both a dance floor where people enter and move, and simultaneously a dancer who even now is checking out the floor (F. Buckland, 2002: 14). My baseline motivation for this study is a curiosity about people’s search for meaning and self-understanding in western culture in the early 21st century. The decline of traditional religious frameworks after the Second World War, led to the remarkable rise of many so called alternative spiritualities or New Religious Movements1 (compare Greenwood, 2000: 8). -

Dance & Spectacle

Proceedings Dance & Spectacle Thirty-third Annual International Conference University of Surrey, Guildford and The Place, London, UK July 8–11, 2010 Society of Dance History Scholars Proceedings Dance & Spectacle Thirty-third Annual International Conference University of Surrey, Guildford and The Place, London, UK July 8–11, 2010 The 2010 SDHS conference, “Dance & Spectacle”, was held July 9–11, 2010, at the University of Surrey, U.K. Each presenter at the conference was invited to contribute to the Proceedings. Those who chose to contribute did so by submitting pdf files, which are assembled here. There was minimal editorial intervention — little more than the addition of page numbers and headers. Authors undertook to adhere to a standard format for fonts, margins, titles, figures or illustrations, order of sections, and so on, but there may be minor differences in format from one paper to another. Individual authors hold the copyrights to their papers. The Society of Dance History Scholars is not legally responsible for any violation of copyright; authors are solely responsible. Published by the Society of Dance History Scholars, 2010. Contents 1. Adair 1 2. Alzalde 9 3. Argade 19 4. Briand 33 5. Carr 49 6. Carter 61 7. Cramer 69 8. David 79 9. Daye 89 10. Friedman 97 11. Grau 109 12. Grotewohl 115 13. Hamp 123 14. Hardin 131 15. Holscher¨ 137 16. Kew 145 17. Klein 153 18. Lenart 159 19. Main 169 20. Mathis-Masury 177 21. Mercer 185 22. Milanovic 195 23. Milazzo 201 24. Monroe 211 25. Mouat 217 26. Paris 229 iv 27. -

University of Movement Giving the Body Credit on Today’S Campuses

MOVEMENT MENU: Fresh Events at MovingArtsNetwork.com CONSCIOUS #6 SPRING 2009 FREE movement for a better world DANCER Soul Motion Inner-Activating with Vinn Martí Shiva Rea, UCLA graduate, transforms the learning curve. University of Movement GIVIng THE BODY CREDIT ON TODAY’S CAMPUSES PLUS AQua MantRA Lyric of Laban DIVING Into DIGItaL Decoding the DNA of Dance UPLIFTING TRendS 10 Shiva Rea shapes a perfect Natarajasana at the Devi Temple in Chidambaram, India. 16 14 5 MENTOR Lyric of Laban Rudolf Laban created a system for mapping movement that is still in use today. Ahead of FEATURES his time in the early 20th century, he created a poetic language of science and motion. 7 WARMUPS 10 Minister of Soul • Recession-proof Trendspotting Departments Diving into the mystery of the present moment • Let Your Moves Be Your Music with Vinn Martí. Editor Mark Metz shares a day of • Debbie Rosas: The Body’s Business movement with the founder of Soul Motion. • Disco Revival Saves Lives 20 VITALITY Drink Up! 14 Laura Cirolia follows her intuition to discover Dance, Dance, Education natural truths about the water we drink and why The convergence of mind and body is good news proper hydration is so important. IN D in the world of academia. 23 SOUNDS Diving into Digital ON PU R 14 In higher education, the buzzword is embodiment. Eric Monkhouse demystifies the digital options facing DJs today and provides helpful tips for EWIJK / New curricula embrace the body at interdisciplinary D O L institutions around the country. performing live with a laptop. -

Women's Experience of 5 Rhythms Dance and the Effects on Their Emotional Wellbeing

Women's experience of 5 Rhythms dance and the effects on their emotional wellbeing Sarah Cook, Karen Ledger and Nadine Scott 2003 Written by Sarah Cook, Karen Ledger and Nadine Scott Published in 2003 By: U.K. Advocacy Network 14-18 West Bar Green Sheffield S1 2DA Tel 0114 2728171 Fax 0114 2727786 Email [email protected] Dancing for Living Women’s experience of 5 Rhythms dance and the effects on their emotional wellbeing Copyright © 2003 Sarah Cook, Karen Ledger and Nadine Scott ISBN 0 9537303 3 6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in any retrieval system of any nature, without the written permission of the copyright holder, to whom the application should be made in writing. Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the contents of this publication. However the U.K. Advocacy Network cannot accept liability for any errors which may occur. Further Copies are available from UKAN at the address above. Printed in England by: Alphagraphics Weston House, West Bar Green Sheffield, S1 2DA Tel: 0114 2750076 Fax: 0114 2750350 1 Contents Page Introduction 3 Research Methods 4 The Participants 9 Our Experience of Dancing 5 Rhythms 11 Transformation Through Dance 14 Effects on Day to Day Living 16 What Helps People to Take Part 18 Personal Accounts 20 Discussion 22 References and Information 26 Acknowledgements 26 Appendix 1, The Dance Workshop Flier 27 Appendix 2, Teaching 5 Rhythms 28 3 are so loaded with different meanings, or Introduction when examined, are unclear.