Toccata Classics TOCC0189 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2012). Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century. In: Lawson, C. and Stowell, R. (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Musical Performance. (pp. 643-695). Cambridge University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/6305/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521896115.027 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/2654833/WORKINGFOLDER/LASL/9780521896115C26.3D 643 [643–695] 5.9.2011 7:13PM . 26 . Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century IAN PACE 1815–1848 Beethoven, Schubert and musical performance in Vienna from the Congress until 1830 As a major centre with a long tradition of performance, Vienna richly reflects -

An Ashgate Book

An Ashgate Book ZZZURXWOHGJHFRP Ernst by Frederick Tatham, England, 1844 (from a picture once owned by W.E. Hill and Sons) HEINRICH WILHELM ERNST: VIRTUOSO VIOLINIST To Marie Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst: Virtuoso Violinist M.W. ROWE Birkbeck College, University of London, UK ROUTLEDGE Routledge Taylor & Francis Group LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 2008 by Ashgate Publishing Published 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © M.W. Rowe 2008 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. M.W. Rowe has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Rowe, Mark W. Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst : virtuoso violinist 1. Ernst, Heinrich Wilhelm, 1812–1865 2. Violinists – Biography I. Title 787.2'092 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rowe, Mark W. Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst : virtuoso violinist / by Mark W. Rowe. p. cm. Includes discography (p. 291), bibliographical references (p. 297), and index. ISBN 978-0-7546-6340-9 (alk. paper) 1. -

Technical Analysis on HW Ernst's Six Etudes for Solo Violin in Multiple

Technical Analysis on Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst’s Six Etudes for Solo Violin in Multiple Voices In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music Violin by Shang Jung Lin M.M. The Boston Conservatory November 2019 Committee Chair: Won-Bin Yim, D.M.A. Abstract Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst was a Moravian violinist and composer who lived between 1814-1865. He was a friend of Brahms, collaborator with Mendelssohn, and was admired by Berlioz and Joachim. He was known as a violin virtuoso and composed many virtuosic works including an arrangement of Schubert’s Erlkönig for solo violin. The focus of this document will be on his Six Etudes for Solo Violin in Multiple Voices (also known as the Six Polyphonic Etudes). These pieces were published without opus number around 1862-1864. The etudes combine many different technical challenges with musical sensitivity. They were so difficult that the composer never gave a public performance of them. No. 6 is the most famous of the set, and has been performed by soloists in recent years. Ernst takes the difficulty level to the extreme and combines different layers of techniques within one hand. For example, the second etude has a passage that combines chords and left-hand pizzicato, and the sixth etude has a passage that combines harmonics with double stops. Etudes from other composers might contain these techniques but not simultaneously. The polyphonic nature allows for this layering of difficulties in Ernst’s Six Polyphonic Etudes. -

Beverly Brown, Violonchelo

BEVERLY BROWN, VIOLONCHELO. UN VIOLONCHELO QUE ENAMORA… Beverly Brown nació en la ciudad de Ann Arbor en Estados Unidos. Estudió la licenciatura en la Universidad de Michigan, donde se graduó con honores. Cursó una maestría en el Conservatorio Peabody de la Universidad Johns Hopkins. Se trasladó a México en 1983, año en el que ingresó a la Orquesta Filarmónica de la UNAM, y en la que es violonchelista principal. Además de sus conciertos con la OFUNAM, ha tocado como solista con orquestas y suele interpretar música de cámara. Asimismo, imparte clases particulares de violonchelo. Giuseppe Maria Clemente dall'Abaco (1710-1805) Nació en Bruselas en 1710. Siguió los pasos de su padre y estudió música. Su talento fue tan evidente que a la edad de 19 años fue nombrado violonchelista en la orquesta de la corte del Príncipe Clemens August von Bayern en Bonn y, 10 años después, llega a ser director de la agrupación. Fue uno de los más grandes violonchelistas de su tiempo. Muy pocas de sus composiciones han sobrevivido, entre ellas sus 11 Capricci para violonchelo solo. En las partituras no hay indicaciones de tempo, dinámica o expresión, es necesario que el solista utilice su conocimiento de la práctica de interpretación e improvise libremente en el estilo marcado. Algunos pasajes muestran un virtuosismo elevado, pero sin dejar de ser sensible, melancólico y expresivo. En particular el Primer Capricci es una pieza de una belleza que nos envuelve desde la primera nota, nos roba el corazón, de una enorme espiritualidad que nos transmite la maestra Beverly Brown. Carlo Alfredo Piatti 1822-1901) Nació cerca de Bérgamo en 1822. -

Toccata Classics TOCC0163 Notes

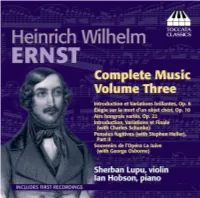

P ERNST Complete Music, Volume Three Introduction et Variations Brillantes en form de Fantaisie pour le violon sur le Quatuor favori de Ludovic de F. Halévy, Op. 6 13:45 1 Introduction: Moderato 3:45 2 Thema: Moderato 1:09 3 Var. 1: Risoluto 1:29 4 Var. 2 1:23 5 Var. 3 1:10 6 Var. 4 1:41 7 Molto Adagio 1:28 8 Allegretto moderato 0:37 9 Finale: Lostesso Tempo 1:00 Élégie sur la mort d’un objet chéri, Op. 10 9:19 10 Introduction by Louis Spohr 2:11 11 Élégie 7:08 Introduction, Variations et Final, Dialogués & Concertans sur une Valse favorite pour Piano et Violon par Charles Schunke et H. W. Ernst, [Schunke’s] Op. 26 13:59 12 Introduzione: Moderato maestoso 3:27 13 Tema 0:57 14 Var. 1: Meno Vivo 0:53 15 Var. 2 0:51 16 Var. 3: Brillante ma moderato 1:13 17 Var. 4: Andantino pastorale 2:05 18 Finale 4:33 2 Pensées Fugitives, Part II 22:39 19 No. 7 Rêverie: Quasi Allegretto 3:49 20 No. 8 Un Caprice: Allegro assai 2:06 21 No. 9 Inquiétude: Adagio 3:28 22 No. 10 Prière pendant l’orage: Allegro non troppo 2:59 23 No. 11 Intermezzo: Allegro poco agitato 3:06 24 No. 12 Thème original de H. W. Ernst: Allegretto 1:12 25 Variation: Moderato 1:25 26 Presto capriccioso: Presto 4:34 Souvenirs de l’Opéra La Juive de F. Halevy pour Piano et Violon Concertants Composés par Osborne et Ernst 8:07 27 Adagio 4:03 28 Allegro 4:04 Airs hongrois variés, Op. -

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) N.P. Troubetskoy—an Outstanding Leader of the Moscow Branch of the Russian Musical Society Olga Glushkova State Institute of art studies Moscow, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The article is devoted to one of the leaders of the The Society existed during the reigns of Emperors Moscow branch of the Imperial Russian musical society, Alexander II, Alexander III, and Nicholas II. Ever since its Prince Nikolai P.Troubetskoy, who participated, along with foundation, the RMS has always been under the auspices of many outstanding representatives of Russian musical culture, Grand Princes and Duchesses: Elena Pavlovna, Nikolai the August patrons of the Society and well-known Konstantinovich, Alexandra Iosifovna, Konstantin philanthropists in the creation of concert and educational Konstantinovich, Sergei Aleksandrovich, and Princess Elena traditions of musical life of Moscow and the Moscow of Sachsen-Altenburg. Conservatory. The main figures of the IRMS were the princes V.F. Keywords—Prince N.P. Troubetskoy; Russian Musical Odoyevsky, N.P. Troubetskoy, D.A. Obolensky and A.A. Society; Moscow conservatory; Ahturka Obolensky, who were philanthropists; the Rubinstein brothers, the pianists; the composers A.S. Dargomyzhsky I. INTRODUCTION and P.I. Tchaikovsky. Many town governors, important industrialists, merchants, and landlords contributed to the The 19th century saw dramatic changes in the history of very existence and elaboration of the Society’s endeavours: Russian musical culture. Undoubtedly, the establishment of M.P. Aznachevsky, S.M. Tretyakov, N.A. Alexeyeva and the Russian Musical Society in 1859 (that also existed under K.S. -

Recomposing National Identity: Four Transcultural Readings of Liszt’S Marche Hongroise D’Après Schubert

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Loya, S. (2016). Recomposing National Identity: Four Transcultural Readings of Liszt’s Marche hongroise d’après Schubert. Journal of the American Musicological Society, 69(2), pp. 409-476. doi: 10.1525/jams.2016.69.2.409 This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/15059/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/jams.2016.69.2.409 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Recomposing National Identity: Four Transcultural Readings of Liszt’s Marche hongroise d’après Schubert SHAY LOYA A Curious Attachment Sometime in 1882, past his seventieth year, Liszt decided that an old piece of his deserved another revision. This resulted in the last of many arrange- ments of the Marche hongroise d’après Schubert, a work that originally took form as the second movement of the Mélodies hongroises d’après Schubert of 1838–39 (S. -

Louise Dulcken Soon Ranked Among the Main Musical Events of the Year

Dulcken, Louise Louise Dulcken soon ranked among the main musical events of the year. Birth name: Louise Marie Louise David The “stars” of the Italian opera such as Giulietta Grisi, Variants: Louise David, Louise Dulken, Louise Marie Giovanni Battista Rubini, Antonio Tamburini and Luigi Louise Dulcken, Louise Marie Louise Dulken, Louisa Lablache took part in them, along with well-known Euro- Dulcken, Louisa David, Louisa Dulken, Louisa Marie pean musicians: the pianists Leopold de Meyer, Alexan- Louisa Dulcken, Louisa Marie Louisa David, Louisa der Dreyschock and – also as pianist – Felix Mendels- Marie Louisa Dulken, Luise Dulcken, Luise David, Luise sohn Bartholdy, the harpists Aline Bertrand, Robert Ni- Dulken, Luise Marie Luise Dulcken, Luise Marie Luise cholas-Charles Bochsa, Théodore Labarre and Elias Pa- David, Luise Marie Luise Dulken rish Alvars, the concertina player Giuligo Regondi, the violinists Charles de Bérot, Camillo Sivori, Leopold Ganz * 20 March 1811 in Hamburg, and Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst as well as the violoncellists † 12 April 1850 in London, Max Bohrer, Moritz Ganz and Jacques Offenbach. Louise Dulcken went on a number of concert tours through, “Madame Dulcken’s Concert. This concert, which is al- among other places, Germany, Russia and Latvia, and fre- ways one of the great affairs of the season, took place quently took part in the concerts of her colleagues in Eng- Monday morning, when the Opera Concert-room was land as well. In addition to her performances and ap- crowded in every part by a most fashionable audience. pearances as pianist, Louise Dulcken was simultaneously The programme was one of more than usual bulk [...]. -

Pedagogical Examination of Henryk Wieniawski's L'école

PEDAGOGICAL EXAMINATION OF HENRYK WIENIAWSKI’S L’ÉCOLE MODERNE OPUS 10 by PAWEL KOZAK (Under the Direction of Levon Ambartsumian and Stephen Valdez) ABSTRACT This document examines the violin techniques found in Wieniawski’s caprices L’école modern Opus 10, and presents practice solutions to the technical challenges. Chapter one provides biographical information on Wieniawski, focusing on his life as a violinist, composer, and pedagogue. Chapter two is an introduction to L’école moderne, containing a list of techniques found within each caprice, and a list of caprices/etudes which should be mastered prior to learning this work. Chapter three examines the technical challenges of each caprice and presents methods for their realization. Chapter four summarizes main ideas discussed in chapter three. INDEX WORDS: Henryk Wieniawski, Wieniawski, L’école moderne, Opus 10, violin caprices. PEDAGOGICAL EXAMINATION OF HENRYK WIENIAWSKI’S L’ÉCOLE MODERNE OPUS 10 by PAWEL KOZAK BM, Augusta State University, 2003 MM, University of Georgia, 2005 A Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2011 © 2011 Pawel Kozak All Rights Reserved PEDAGOGICAL EXAMINATION OF HENRYK WIENIAWSKI’S L’ÉCOLE MODERNE OPUS 10 by PAWEL KOZAK Major Professors: Levon Ambartsumian Stephen Valdez Committee: Milton Masciadri Evgeny Rivkin Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my sincere gratitude to my doctoral committee members for their continued support of this document. I would especially like to thank Dr. -

5040167-44026A-5060113443113

HEINRICH WILHELM ERNST: COMPLETE WORKS, VOLUME SIX by Mark Rowe Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst was one of the most important violin virtuosi of the nineteenth century. Born to Jewish parents in Brno on 8 June 1812, he began to learn the violin at the age of nine, and his progress was soon so rapid that he transferred to the Vienna Conservatoire in 1825. Here he studied under Jakob Böhm (for violin) and Ignaz Seyfried (for composition), but it was Paganini’s Viennese concerts in 1828 which inspired the young virtuoso to set off on an ambitious solo tour of Germany in 1829–30 – sometimes entering into competition with Paganini himself – before heading for Paris in 1831. Remorseless practice ensured that by 1834 he was appearing in concerts with Liszt and Chopin, and his success became unequivocal when he triumphed over the now ailing Paganini in Marseilles in 1837. During the next eleven years, Ernst completed spectacularly successful tours of France, the Austrian Empire, Germany, Poland, the Low Countries, Britain, Scandinavia and Russia, before the 1848 Revolution put a temporary end to professional musical activity across the continent. He spent a good deal of the next eight years in Britain – one of the few major European countries unaffected by revolution – but he still undertook a handful of extended foreign tours, and on one of these excursions, to France in 1852, he met the actress Amélie-Siona Lévy. By the time they married, two years later, Ernst’s health – which had been delicate since his early twenties – was beginning to fail, and in 1858 he was forced to retire from the stage. -

TCHAIKOVSKY EDITION Liner Notes and Sung Texts

TCHAIKOVSKY EDITION Liner notes and sung texts Liner notes A RICH, HUMANE LEGACY: THE MUSIC OF PYOTR ILYICH of Mozart’s spirit that he later paid homage in so many works TCHAIKOVSKY which turned out to be neo‐Classical avant la lettre. As Julian Barnes so elegantly demonstrated in his novel Flaubert’s Parrot, you can provide a number of selective, conflicting Even this is to limit the sheer encyclopaedic breadth of biographies around a great creative artist’s life, and any one of Tchaikovsky’s composing genius. He wrote in every medium them will be true. By those standards, one could counter Harold conceivable at the time, and if not every opus can possibly be at C. Schonberg’s thumbnail sketch of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky as ‘a his highest level of inspiration, there are masterpieces in each nervous, hypochondriacal, unhappy man – unhappy at home, genre: opera, song, symphonic music, occasion‐pieces (which unhappy away from home’, with a portrait of the composer as an includes the ‘1812 Overture’ – much‐maligned, but does what it older man: confident, healthy, a keen traveller, a generous spirit says on the tin), chamber works and choral settings of the who had come to terms with his demons even if they occasionally Russian Orthodox service, which it was then regarded as popped up to haunt him, and a lover of the Russian landscape pioneering to even attempt to promote. who was very much at peace with the natural beauty of the country surroundings he had chosen as his dwelling. His first fully fledged steps in composition contradict one perceived dichotomy: between his association with the Neither image is, of course, the whole story, and it is only slowly Germanically motivated founder‐brothers of Russia’s two that the public is learning, thanks to a wider retrospective on academic institutions – the St Petersburg Conservatoire founded Tchaikovsky’s genius in the round, to balance the tabloidised first by Anton Rubinstein in 1862, and its Moscow counterpart portrait with the less sensationalised second.