The Bechdel Test

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sofia Coppola and the Significance of an Appealing Aesthetic

SOFIA COPPOLA AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF AN APPEALING AESTHETIC by LEILA OZERAN A THESIS Presented to the Department of Cinema Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Leila Ozeran for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Cinema Studies to be taken June 2016 Title: Sofia Coppola and the Significance of an Appealing Aesthetic Approved: r--~ ~ Professor Priscilla Pena Ovalle This thesis grew out of an interest in the films of female directors, producers, and writers and the substantially lower opportunities for such filmmakers in Hollywood and Independent film. The particular look and atmosphere which Sofia Coppola is able to compose in her five films is a point of interest and a viable course of study. This project uses her fifth and latest film, Bling Ring (2013), to showcase Coppola's merits as a filmmaker at the intersection of box office and critical appeal. I first describe the current filmmaking landscape in terms of gender. Using studies by Dr. Martha Lauzen from San Diego State University and the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media to illustrate the statistical lack of a female presence in creative film roles and also why it is important to have women represented in above-the-line positions. Then I used close readings of Bling Ring to analyze formal aspects of Sofia Coppola's filmmaking style namely her use of distinct color palettes, provocative soundtracks, car shots, and tableaus. Third and lastly I went on to describe the sociocultural aspects of Coppola's interpretation of the "Sling Ring." The way the film explores the relationships between characters, portrays parents as absent or misguided, and through film form shows the pervasiveness of celebrity culture, Sofia Coppola has given Bling Ring has a central ii message, substance, and meaning: glamorous contemporary celebrity culture can have dangerous consequences on unchecked youth. -

Female Improvisational Poets: Challenges and Achievements in the Twentieth Century

FEMALE .... improvisational - ,I: t -,· POETS ...~1 Challenges and Achievements in the Twentieth Century In December 2009, 14,500 people met at the Bilbao Exhibi tion Centre in the Basque Country to attend an improvised poetry contest.Forty-four poets took part in the 2009 literary tournament, and eight of them made it to the final. After a long day of literary competition, Maialen Lujanbio won and received the award: a big black txapela or Basque beret. That day the Basques achieved a triple triumph. First, thou sands of people had gathered for an entire day to follow a lite rary contest, and many more had attended the event via the web all over the world. Second, all these people had followed this event entirely in Basque, a language that had been prohi bited for decades during the harsh years of the Francoist dic tatorship.And third, Lujanbio had become the first woman to win the championship in the history of the Basques. After being crowned with the txapela, Lujanbio stepped up to the microphone and sung a bertso or improvised poem refe rring to the struggle of the Basques for their language and the struggle of Basque women for their rights. It was a unique moment in the history of an ancient nation that counts its past in tens of millennia: I remember the laundry that grandmothers of earlier times carried on the cushion [ on their heads J I remember the grandmother of old times and today's mothers and daughters.... • pr .. Center for Basque Studies # avisatiana University of Nevada, Reno ISBN 978-1-949805-04-8 90000 9 781949 805048 ■ .~--- t _:~A) Conference Papers Series No. -

FIRST CENTURY AVANT-GARDE FILM RUTH NOVACZEK a Thesis

NEW VERNACULARS AND FEMININE ECRITURE; TWENTY- FIRST CENTURY AVANT-GARDE FILM RUTH NOVACZEK A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 Acknowledgements Thanks to Chris Kraus, Eileen Myles and Rachel Garfield for boosting my morale in times of great uncertainty. To my supervisors Michael Mazière and Rosie Thomas for rigorous critique and sound advice. To Jelena Stojkovic, Alisa Lebow and Basak Ertur for camaraderie and encouragement. To my father Alfred for support. To Lucy Harris and Sophie Mayer for excellent editorial consultancy. To Anya Lewin, Gillian Wylde, Cathy Gelbin, Mark Pringle and Helen Pritchard who helped a lot one way or another. And to all the filmmakers, writers, artists and poets who make this work what it is. Abstract New Vernaculars and Feminine Ecriture; Twenty First Century Avant-Garde Film. Ruth Novaczek This practice-based research project explores the parameters of – and aims to construct – a new film language for a feminine écriture within a twenty first century avant-garde practice. My two films, Radio and The New World, together with my contextualising thesis, ask how new vernaculars might construct subjectivity in the contemporary moment. Both films draw on classical and independent cinema to revisit the remix in a feminist context. Using appropriated and live-action footage the five short films that comprise Radio are collaged and subjective, representing an imagined world of short, chaptered ‘songs’ inside a radio set. The New World also uses both live-action and found footage to inscribe a feminist transnational world, in which the narrative is continuous and its trajectory bridges, rather than juxtaposes, the stories it tells. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

My Name Is Corrina and I'm the Founder of Bechdel Test Fest

My name is Corrina and I’m the founder of Bechdel Test Fest - an ongoing celebration of women in film. I’m also a freelance critic for Empire Magazine and most recently have produced a documentary on Ava Duvernay for the BBC and have had the pleasure of working with debbie tucker green on the release of her forthcoming new film. In addition I am the resident film critic for Sunday Brunch once a month on Channel 4. I previously worked for Picturehouse Entertainment distribution company but now... My name is corrina and I’m the founder of Bechdel Test Fest - an ongoing celebration of women in film. I’m also a freelance critic for Empire Magazine and most recently have produced a documentary on Ava Duvernay for the BBC and have had the pleasure of working with debbie tucker green on the release of her forthcoming new film. In addition I am the resident film critic for Sunday Brunch once a month on Channel 4 I previously worked for Picturehouse Entertainment distribution company but now.... ...For the day job, I am the arts and culture comms officer for Hackney Council which has me working on events such as Windrush Festival, Hackney’s Anti Racism Plan, Carnival, Black History Season, Hackney Black History Curriculum and the forthcoming Census. I’m Hackney born and bred so... Right now, due to the pandemic, Bechdel Test Fest has been unable to screen films of course but we are still committed to celebrating the work of female-identifying women in film via our Friday newsletter and social which promotes all the week’s new releases and our podcast Who Is She which spotlights and usually interviews a brilliant female filmmaker. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin J

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement Justin J. Grandinetti James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Rhetoric Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grandinetti, Justin J., "Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement" (2015). Masters Theses. 43. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/43 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Occupy the Future: A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin Grandinetti A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communication May 2015 Dedication Page This thesis is dedicated to the world’s revolutionaries and all the individuals working to make the planet a better place for future generations. ii Acknowledgements I’d like to thank a number of people for their assistance and support with this thesis project. First, a heartfelt thank you to my thesis chair, Dr. Jim Zimmerman, for always being there to make suggestions about my drafts, talk about ideas, and keep me on schedule. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Identifying Missing Component in the Bechdel Test Using Principal Component Analysis Method Raghav Lakhotia, Chandra Kanth Nagesh, Krishna Madgula

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Computer and Systems Engineering Vol:13, No:6, 2019 Identifying Missing Component in the Bechdel Test Using Principal Component Analysis Method Raghav Lakhotia, Chandra Kanth Nagesh, Krishna Madgula about how women are under-represented on screen. According Abstract—A lot has been said and discussed regarding the to the report "Celluloid Ceiling" [3], "women comprised only rationale and significance of the Bechdel Score. It became a digital 18% of all the directors, writers, producers, editors, executive sensation in 2013, when Swedish cinemas began to showcase the and cinematographers working on the top 250 domestic Bechdel test score of a film alongside its rating. The test has drawn grossing films in 2017". While in 2016, only 12% of films out criticism from experts and the film fraternity regarding its use to rate the female presence in a movie. The pundits believe that the score is of 900 had a balanced cast [4]. Men outnumber women in the too simplified and the underlying criteria of a film to pass the test film industry as well. The issue has long prevailed in the must include 1) at least two women, 2) who have at least one industry since, but the question arises; did we highlight this dialogue, 3) about something other than a man, is egregious. In this gender bias to the extent that we should have? research, we have considered a few more parameters which highlight In 1985, Alison Bechdel, an American cartoonist, invented how we represent females in film, like the number of female a score [5] to gauge gender equality on screen. -

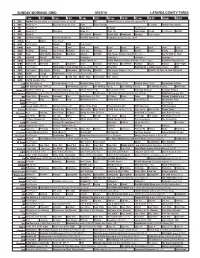

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/23/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 Am 7:30 8 Am 8:30 9 Am 9:30 10 Am 10:30 11 Am 11:30 12 Pm 12:30 2 CBS Football New York Giants Vs

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/23/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS Football New York Giants vs. Los Angeles Rams. (6:30) (N) NFL Football Raiders at Jacksonville Jaguars. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Figure Skating F1 Count Formula One Racing 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Regional Coverage. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Rick Steves’ Europe Travel Skills (TVG) Å Age Fix With Dr. Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Tigres República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Home Alone 2: Lost in New York ›› (1992) (PG) Zona NBA Next Day Air › (2009) Donald Faison. -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10. -

Author Alison Bechdel's Acceptance of Her Homosexual Iden

Acceptance versus Suppression: Homosexuality in the “Fun Home” Author Alison Bechdel’s acceptance of her homosexual identity, as illustrated in Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, is a more fluid experience than her father’s similar realization. Their unique first experiences with their sexuality play a role in their definitions of homosexuality. Both also spend their emerging adulthood years in different settings: Alison in a college setting and Bruce in a small town. Literature is a common bond between the two throughout their relationship, but affects each in different ways, particularly in reference to understanding their sexuality. The immense distinctions in their encounters and experiences involving their homosexuality ultimately shaped their development: Alison into a woman accepting of her identity and Bruce into a man suppressing his. Each character’s first experience with homosexuality differed in everything from their age at the time to the type of person with whom it occurred. Bruce had his first encounter when he was young with a worker at his family farm. Here, he describes it as “nice”, rather than a traumatizing encounter (Bechdel 220). Inspecting the drawings, his face tells a different story. Because of how casually he refers to it, he still seems unwilling to fully admit to his gratification of the experience, even if it was something he enjoyed. When Alison’s mother first informs Alison that her dad is also homosexual, she blames it on this experience (58). 1 Her mother stutters, showing her acknowledgement that her husband’s encounter with the farm hand was not molestation, but something he wanted and most likely enjoyed. -

My Favourite Film Trailer About Movie

BRIDE WARS MY FAVOURITE FILM TRAILER ABOUT MOVIE American romantic comedy film Director: Gary Wincik Writers: Greg DePaul, Casey Wilson Premiere: (USA) 9th January 2009 (SLO) 5th February 2009 Boston, New York City 89min ACTORS and ACTRESSES Kate Hudons as Liv Lerner Successful woman who attemps to be perfect. Anne Hathaway as Emma Allen Middle school teacher who takes care of everyone. ACTORS and ACTRESSES Fletcher Daniel Marion Nathan Candice Bergen as Marion St. Claire (very famous wedding planner) Chris Pratt as Fletcher Flemson (Emma's fiance) Bryan Greenberg as Nathan (Liv's younger brother who is in love with Emma) Steve Howey as Daniel Williams (Liv's fiance) Some words which you possible won‘t understand? • Childhood – otroštvo • Fiance – zaročenec • Sun tanning – porjavitvena krema, solarij • Alternative dance instructor – nadomesten učitelj plesa • To torture – mučiti • Highlights – prameni STORY • Story is about two best friends. • Dreaming about the perfect wedding. • Felling in love with the idea. • So when they grew up, became engaged to their boyfriends. • Starting planning the wedding. First step: reservation. • They picked the date. • Few days later, they found out.. • None of them didn‘t want changed her plans. • Their fiances suggested a double wedding STORY • So war between brides began. • Each wanted to destroy the wedding of another one. • Liv stole Emma's dream DJ. • With help of spray tanning she changed Emma's skin to orange. • Emma sent Liv cookies and chocolate so she will gain weight and not fit her dress. • She also changed Liv's hair highlights to blue. • Uncover end! »They haven't spoken in a week.