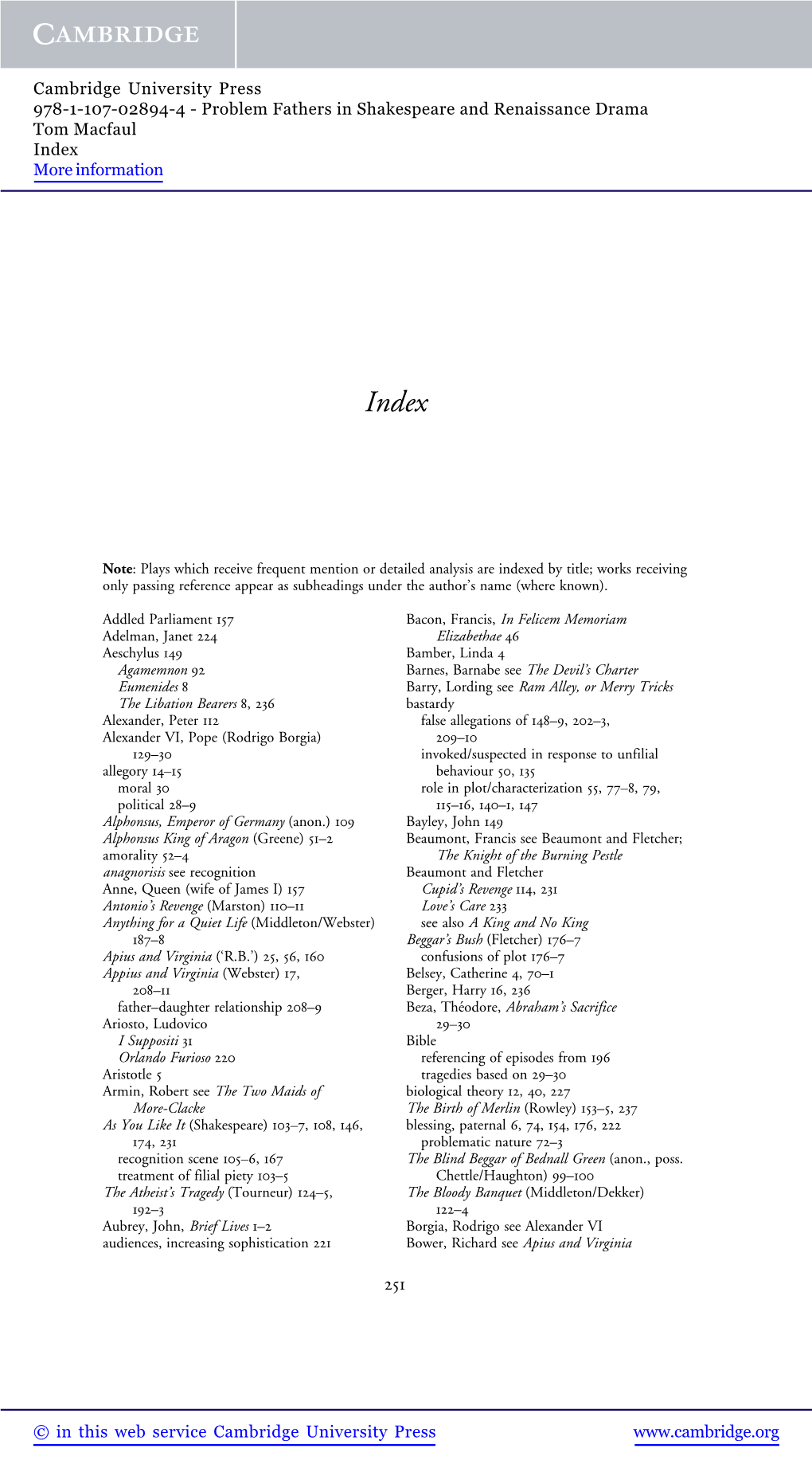

Problem Fathers in Shakespeare and Renaissance Drama Tom Macfaul Index More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fantasies of Necrophilia in Early Modern English Drama

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2014 Exquisite Corpses: Fantasies of Necrophilia in Early Modern English Drama Linda K. Neiberg Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1420 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXQUISITE CORPSES: FANTASIES OF NECROPHILIA IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH DRAMA by LINDA K. NEIBERG A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ii © 2014 LINDA K. NEIBERG All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mario DiGangi Date Chair of Examining Committee Carrie Hintz Date Acting Executive Officer Mario DiGangi Richard C. McCoy Steven F. Kruger Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract EXQUISITE CORPSES: FANTASIES OF NECROPHILIA IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH DRAMA by LINDA K. NEIBERG Adviser: Professor Mario DiGangi My dissertation examines representations of necrophilia in Elizabethan and Jacobean drama. From the 1580s, when London’s theatres began to flourish, until their closure by Parliament in 1642, necrophilia was deployed as a dramatic device in a remarkable number of plays. -

Actes Des Congrès De La Société Française Shakespeare, 33 | 2015 Middleton Beyond the Canon 2

Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 33 | 2015 Shakespeare 450 Middleton beyond the Canon Daniela Guardamagna Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/3394 DOI: 10.4000/shakespeare.3394 ISSN: 2271-6424 Publisher Société Française Shakespeare Electronic reference Daniela Guardamagna, « Middleton beyond the Canon », Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare [Online], 33 | 2015, Online since 10 October 2015, connection on 08 June 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/3394 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/shakespeare.3394 This text was automatically generated on 8 June 2020. © SFS Middleton beyond the Canon 1 Middleton beyond the Canon Daniela Guardamagna 1 The old canon of Thomas Middleton1 has been deeply modified in the last forty years by attribution studies, by the analysis of philologists and the work of MacDonald P. Jackson, David Lake and Roger Holdsworth,2 and especially after the issue of what has been defined as “Middleton’s First Folio”, that is his Collected Works and Textual Companion, edited by Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino.3 2 Critics are now aware that there are many clues hinting at the fact that the ‘new Middleton’ is very different from the author that was proposed till the last decades of the 20th century, that is the cold, misogynist, clinical analyst of the society around him (“a 17th-century Ibsen or Zola”, as he was defined4), and that the new figure presents striking features which greatly modify our perception of his work. 3 In this paper I will concentrate on a specific instance concerning the new canon: the modification of female characters that becomes apparent in Middleton’s writing, considering the new plays, the tragedies in particular, that have been definitely attributed to him in the 2007 Collected Works. -

Why Does Plato's Laws Exist?

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Why Does Plato's Laws Exist? Harold Parker University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Harold, "Why Does Plato's Laws Exist?" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2515. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2515 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2515 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Why Does Plato's Laws Exist? Abstract If the ideal city described at length in Plato’s Republic is a perfect and philosophically attractive encapsulation of Plato’s political philosophy, why does Plato go on to write the Laws – which also describes an ideal city, albeit one very different from the Republic? The fundamental challenge of scholarship concerning the Laws is to supply a comprehensive account of the dialogue that explains all aspects of it while also distinguishing the Laws from the Republic in a way that does not devalue the Laws as a mere afterthought to the Republic. Past attempts at meeting this challenge, I argue, can be classified under the headings of the democratic, legal, and demiurgic approaches. Although each is prima facie plausible, each also faces its own set of problems. Furthermore, none are truly capable of explaining the Laws in its full specificity; the intricate array of customs, regulations, and practices making up the life of the city described form a complex totality not reducible to the concept of democracy, the rule of law, or demiurgy. -

The Ethics of Eating Animals in Tudor and Stuart Theaters

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: THE ETHICS OF EATING ANIMALS IN TUDOR AND STUART THEATERS Rob Wakeman, Doctor of Philosophy, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Professors Theresa Coletti and Theodore B. Leinwand Department of English, University of Maryland A pressing challenge for the study of animal ethics in early modern literature is the very breadth of the category “animal,” which occludes the distinct ecological and economic roles of different species. Understanding the significance of deer to a hunter as distinct from the meaning of swine for a London pork vendor requires a historical investigation into humans’ ecological and cultural relationships with individual animals. For the constituents of England’s agricultural networks – shepherds, butchers, fishwives, eaters at tables high and low – animals matter differently. While recent scholarship on food and animal ethics often emphasizes ecological reciprocation, I insist that this mutualism is always out of balance, both across and within species lines. Focusing on drama by William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and the anonymous authors of late medieval biblical plays, my research investigates how sixteenth-century theaters use food animals to mediate and negotiate the complexities of a changing meat economy. On the English stage, playwrights use food animals to impress the ethico-political implications of land enclosure, forest emparkment, the search for new fisheries, and air and water pollution from urban slaughterhouses and markets. Concurrent developments in animal husbandry and theatrical production in the period thus led to new ideas about emplacement, embodiment, and the ethics of interspecies interdependence. THE ETHICS OF EATING ANIMALS IN TUDOR AND STUART THEATERS by Rob Wakeman Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Advisory Committee: Professor Theresa Coletti, Co-Chair Professor Theodore B. -

The Prosecution and Punishment of Animals and Lifeless Things in the Middle Ages and Modern Times

THE PROSECUTION AND PUNISHMENT OF ANIMALS AND LIFELESS THINGS IN THE MIDDLE AGES AND MODERN TIMES. The Prytaneum was the Hotel de Ville of Athens as of every Greek town. In it was the common hearth of the city, which represented the unity and vitality of the community. From its perpetual fire, colonists, like the American Indians, would carry sparks to their new homes, as a symbol of fealty to the mother city, and here in very early times the prytanis or chief- tain probably dwvelt. In the Prytaneum at Athens the statues of Eirene (Peace) and Hestia (Ilearth) stood; foreign ambassa- dors, famous citizens, athletes, and strangers were entertained there at the public expense; the laws of the great law-giver Solon were displayed within it and before his day the chief archon made it his home. One of the important features of the Prytaneum at Athens were the curious murder trials held in its immediate vicinity. Many Greek writers mention these trials, which appear to have comprehended three kinds of cases. In the first place, if a murderer was unknown or could not be found, he was never- theless tri'ed at this court.' Then inanimate things-such as stones, beams, pliece of iron, ctc.,-which had caused the death of a man by falling upon him-were put on trial at the Pry- tancuni ;2 and lastly animals, which had similarly been the cause 3 of death. Though all these trials were of a ceremonial character, they were carried on with due process of law. Thus, as in all murder trials at Athens, because of 'the religious feeling back of them that such crimes were against the gods as much as against men, they took place in the open air, that the judges might not be contaminated by the pollution supposed to exhale from the 'Aristotle, Constitulion (if :thens, 57, 4; Pollux, Vill, x2o; cf. -

The Bible in Spain - George Borrow

THE BIBLE IN SPAIN - GEORGE BORROW AUTHOR'S PREFACE It is very seldom that the preface of a work is read; indeed, of late years, most books have been sent into the world without any. I deem it, however, advisable to write a preface, and to this I humbly call the attention of the courteous reader, as its perusal will not a little tend to the proper understanding and appreciation of these volumes. The work now offered to the public, and which is styled THE BIBLE IN SPAIN, consists of a narrative of what occurred to me during a residence in that country, to which I was sent by the Bible Society, as its agent for the purpose of printing and circulating the Scriptures. It comprehends, however, certain journeys and adventures in Portugal, and leaves me at last in "the land of the Corahai," to which region, after having undergone considerable buffeting in Spain, I found it expedient to retire for a season. It is very probable that had I visited Spain from mere curiosity, or with a view of passing a year or two agreeably, I should never have attempted to give any detailed account of my proceedings, or of what I heard and saw. I am no tourist, no writer of books of travels; but I went there on a somewhat remarkable errand, which necessarily led me into strange situations and positions, involved me in difficulties and perplexities, and brought me into contact with people of all descriptions and grades; so that, upon the whole, I flatter myself that a narrative of such a pilgrimage may not be wholly uninteresting to the public, more especially as the subject is not trite; for though various books have been published about Spain, I believe that the present is the only one in existence which treats of missionary labour in that country. -

Webster and the Running Footman

Early Theatre 13.1 (2010) David Carnegie Running over the Stage: Webster and the Running Footman Although the frequent stage direction ‘passing over the stage’ has provoked much discussion as to its precise meaning,1 ‘running over the stage’ has attracted much less attention. Indeed, the famous Elizabethan theatrical clown Will Kemp achieved more fame by morris dancing than by running, though in his case heightened by being from London to Norwich.2 In early modern English drama there are, nevertheless, many kinds of running called for in stage directions. Alan Dessen and Leslie Thomson’s Dictionary of Stage Directions in English Drama, 1580–1642 lists roughly 260 examples under the headwords ‘running’, ‘hastily, in haste’, and others, divided into four categories.3 1. ‘enter/exit running/in haste’; this is the largest group, and includes examples such as ‘Enter in haste … a footman’ (Middleton, A Mad World My Masters 2.1.6.2–6.3), ‘Enter Bullithrumble, the shepherd, running in haste’ (? Greene, Selimus sc. 10; line 1877), ‘Enter Segasto running, and Amadine after him, being pursued with a bear’ (Anon., Mucedorus B1r), and presumably ‘Enter Juliet somewhat fast, and embraceth Romeo’ (Shake- speare, Romeo and Juliet 2.5.15.1). 2. ‘runs in/away/out/off ’; a typical example is ‘Lion roars. Thisbe … runs off’ (Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream 5.1.253.1). 3. ‘runs at someone or is run through with a sword’; examples include ‘He draws his rapier, offers to run at Piero; but Maria holds his arm and stays him’ (Marston, Antonio’s Revenge 1.2 [Q 1.4].375–6), and ‘Flamineo runs Marcello through’ (Webster, The White Devil 5.2.14). -

Why Was Edward De Vere Defamed on Stage—And His Death Unnoticed?

Why Was Edward de Vere Defamed on Stage—and His Death Unnoticed? by Katherine Chiljan dward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, died on June 24, 1604. To our knowledge, there was neither public recognition of his death nor Enotice made in personal letters or diaries. His funeral, if one oc- curred, went unremarked. Putting aside his greatness as the poet-playwright “William Shakespeare,” his pen name, Oxford was one of the most senior nobles in the land and the Lord Great Chamberlain of England. During his life, numerous authors dedicated 27 books on diverse subjects to Oxford; of these authors, seven were still alive at the time of his death,1 including John Lyly and Anthony Munday, his former secretaries who were also dramatists. Moreover, despite the various scandals that touched him, Oxford remained an important courtier throughout his life: Queen Elizabeth granted him a £1,000 annuity in 1586 for no stated reason—an extraordinary gesture for the frugal monarch—and King James continued this annuity after he ascend- ed the throne in 1603. Why, then, the silence after Oxford had died? Could the answer be because he was a poet and playwright? Although such activity was considered a déclassé or even fantastical hobby for a nobleman, recognition after death would have been socially acceptable. For example, the courtier poet Sir Philip Sidney (d. 1586) had no creative works published in his lifetime, but his pastoral novel, Arcadia, was published four years after his death, with Sidney’s full name on the title page. Three years after that, Sidney’s sister, the Countess of Pembroke, published her own version of it. -

Article (Published Version)

Article 'Our Other Shakespeare'? Thomas Middleton and the Canon ERNE, Lukas Christian Reference ERNE, Lukas Christian. 'Our Other Shakespeare'? Thomas Middleton and the Canon. Modern Philology, 2010, vol. 107, no. 3, p. 493-505 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:14484 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 492 MODERN PHILOLOGY absorbs and reinterprets a vast array of Renaissance cultural systems. "Our other Shakespeare": Thomas Middleton What is outside and what is inside, the corporeal world and the mental and the Canon one, are "similar"; they are vivified and governed by the divine spirit in Walker's that emanates from the Sun, "the body of the anima mundi" LUKAS ERNE correct interpretation. 51 Campanella's philosopher has a sacred role, in that by fathoming the mysterious dynamics of the real through scien- University of Geneva tific research, he performs a religious ritual that celebrates God's infi- nite wisdom. To T. S. Eliot, Middleton was the author of "six or seven great plays." 1 It turns out that he is more than that. The dramatic canon as defined by the Oxford Middleton—under the general editorship of Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino, leading a team of seventy-five contributors—con- sists of eighteen sole-authored plays, ten extant collaborative plays, and two adaptations of plays written by someone else. The thirty plays, writ ten for at least seven different companies, cover the full generic range of early modern drama: eight tragedies, fourteen comedies, two English history plays, and six tragicomedies. These figures invite comparison with Shakespeare: ten tragedies, thirteen comedies, ten or (if we count Edward III) eleven histories, and five tragicomedies or romances (if we add Pericles and < Two Noble Kinsmen to those in the First Folio). -

THE DOMESTIC DRAMA of THOMAS DEKKER, 1599-1621 By

CHALLENGING THE HOMILETIC TRADITION: THE DOMESTIC DRAMA OF THOMAS DEKKER, 1599-1621 By VIVIANA COMENSOLI B.A.(Hons.), Simon Fraser University, 1975 M.A., Simon Fraser University, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of English) We accept, this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA December 1984 (js) Viviana Comensoli, 1984 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 DE-6 (3/81) ABSTRACT The dissertation reappraises Thomas Dekker's dramatic achievement through an examination of his contribution to the development of Elizabethan-Jacobean domestic drama. Dekker's alterations and modifications of two essential features of early English domestic drama—the homiletic pattern of sin, punishment, and repentance, which the genre inherited from the morality tradition, and the glorification of the cult of domesticity—attest to a complex moral and dramatic vision which critics have generally ignored. In Patient Grissil, his earliest extant domestic play, which portrays ambivalently the vicissitudes of marital and family life, Dekker combines an allegorical superstructure with a realistic setting. -

The Private Theaters in Crisis: Strategies at Blackfriars and Paul’S, 1606–07

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PRIVATE THEATERS IN CRISIS: STRATEGIES AT BLACKFRIARS AND PAUL’S, 1606–07 Christopher Bryan Love, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Professor Theodore B. Leinwand, Department of English This study addresses the ways in which the managers and principal playwrights at second Paul’s and second Blackfriars approached opportunities in the tumultuous 1606–07 period, when the two troupes were affected by extended plague closures and threatened by the authorities because of the Blackfriars’ performance of offensive satires. I begin by demonstrating that Paul’s and Blackfriars did not neatly conform to the social and literary categories or commercial models typically employed by scholars. Instead, they were collaborative institutions that readily adapted to different circumstances and situations. Their small size, different schedules, and different economics gave them a flexibility generally unavailable to the larger, more thoroughly commercial adult companies. Each chapter explores a strategy used by the companies and their playwrights to negotiate a tumultuous theatrical market. The first chapter discusses the mercenary methods employed by the private children’s theaters. Occasionally, plays or play topics were commissioned by playgoers, and some performances at Paul’s and Blackfriars may even have been “private” in the sense of closed performances for exclusive audiences. In this context, I discuss Francis Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle (Blackfriars, 1607), in which Beaumont uses the boorish citizens George and Nell to lay open the private theaters’ mercenary methods and emphasize sophisticated playgoers’ stake in the Blackfriars theater. The second chapter discusses the ways private-theater playwrights used intertextuality to entertain the better sort of playgoers, especially those who might buy quartos of plays. -

The Significance of the Family in Five Renaissance Plays

Tragedies of Blood The Significance of the Family in Five Renaissance Plays A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English in the University of Canterbury by Hester M. M. Lees-Jeffries University of Canterbury 1998 p(, ", r I /(6/ n (, Contents Acknowledgements 1 Abstract 2 Introduction 3 The Historiographical Background 9 The Critical Frame 12 Part One: Natural and Unnatural 19 Part Two: Prison and Sanctuary 71 Conclusion 123 Bibliography 125 -6 1 Acknowled gemen ts I would like to thank David Gunby for being such an interested, supportive and sensible supervisor, and the occupants (and habitues) of 320A, past and present (especially Jane and Chanel) for their friendship, interest and energy. Outside the Department, I thank Emily, Liz, Brigitte and James for their support and friendship, and my own family, the idiosyncrasies of whom pale into insignificance beside those of the others that I have here made my study. 2 Abstract In this thesis, I examine the functions and significance of the family in five English tragedies from the period 1607-30. Drawing on Renaissance texts in which the family is employed as the fundamental analogue of social and moral order, I argue that the prominence of the family in these plays attests to an enduring belief in the need for order and structure in society, which their sensationalist depictions of depravities such as adultery, incest, bastardy and murder should not be allowed to obscure. In doing so, I reject criticism which regards these plays' view of human nature and society as 'progressive', modern and pessimistic, arguing instead that their ethos is implicitly conservative and, if at times cynical, nostalgic.