You Are Here Art After the Internet You Are Here — Art After the Internet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

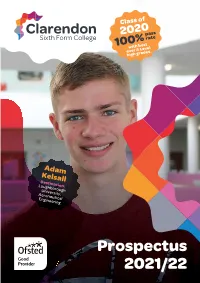

Prospectus 2021/22

Lewis Kelsall 2020 Destination:e Cambridg 100 with bestLeve l University, ever A . Engineering high grades Adam Kelsall Destination: Loughborough University Aeronautical, Engineering Clarendon Sixth Form College Camp Street Ashton-under-Lyne OL6 6DF Prospectus 2021/22 03 Message from the Principal 04 Choose a ‘Good’ College 05 Results day success 06 What courses are on offer? 07 Choosing your level and entry requirements 08 How to apply 09 Study programme 12 Study skills and independent learning programme 13 Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) and Futures Programme 14 Student Hub 16 Dates for your diary 17 Travel and transport 18 University courses at Tameside College 19 A year in the life of... Course Areas 22 Creative Industries 32 Business 36 Computing 40 English and Languages 44 Humanities 50 Science, Mathematics and Engineering 58 Social Sciences 64 Performing Arts 71 Sports Studies and Public Services 02 Clarendon Sixth Form College Prospectus 2021/22 Welcome from the Principal Welcome to Clarendon Sixth Form College. As a top performing college in The academic and support Greater Manchester for school leavers, package to help students achieve while we aim very high for our students. Our studying is exceptional. It is personalised students have outstanding success to your needs and you will have access to a rates in Greater Manchester, with a range of first class support services at each 100% pass rate. stage of your learning journey. As a student, your career aspirations and This support package enables our students your college experience are very important to operate successfully in the future stages of to us. -

The Archival Media Art Experience

The Archival Media Art Experience Master Thesis Handed in to School of Music, Music Therapy, Psychology, Communication, Art & Technology (MPACT) Aalborg University Head of Department Tom Nyvang, Ph.D and the Media Arts Cultures Consortium Course Media Arts Cultures 1st Supervisor Morten Søndergaard, Ph.d. By: Emőke Majohunbo Bada inscription number: 01564275 January 2018 Abstract Topic: The Archival Media Art Experience Author: Emőke Majohunbo Bada Supervisor: Morten Søndergaard, Ph.d. Course/Year: Media Arts Cultures, 2015-2017 4th Semester Placement: Aalborg University Pages: 91 Content: The most immediate way of experiencing an art piece is personal contact with the artefact itself, however often due to the physical limitations of both art object and art consumer, the viewer’s opportunity of encountering an given work in real life and real time is not always feasible. Archives, through media technologies, allow people to experience artworks from a distance. As a result the experience the artwork supplies may change. What factors determine this change, are they apparent to viewers of archives? Before investigating archival art experiences, the following main terms: experience, engagement, media art, technology, internet and archive need to be explored thoroughly. The following authors such as Dewey, Fenner, Ricardo, Zielinksi, Idhe, Hine, Hogan and Manoff are but a few of those whom the thesis bases its theory upon. As all experiences are highly personal phenomena, therefore interviewing people about their experiences was chosen as method for gathering such information. To guide the participants in the research, five different media artworks were chosen carefully as case studies to observe the particulars of the archival experience. -

Tommy Clarke 18 Wolf Ademeit 20 Yann Arthus-Bertrand

Contents 2 The Frame & Arts 4 Samsung Collection 6 Curation Story Artist Profiles 8 Bohnchang Koo 10 Luisa Lambri 12 ruby onyinyechi amanze 14 Todd Eberle 16 Tommy Clarke 18 Wolf Ademeit 20 Yann Arthus-Bertrand 22 Samsung Collection at a Glance 29 Art Store Gallery Partners 30 ALBERTINA 32 Artspace 34 LUMAS 36 MAGNUM PHOTOS 38 Museo Del Prado Collection 40 Saatchi Art 42 Sedition 44 How to Use 46 My Collection 50 The Frame Specifications Tommy Clarke, Playa Shoreline (2015) 1 The Frame & ArtsArt The Frame. Art when it's off, TV when it's on. Introducing The Frame, a TV that elegantly enables you to make anye spac more welcoming, more entertaining and more inspiring. Turn on The Frame in TV mode and watch a beautiful 4K UHD Smart TV with outstanding detail and picture quality. Turn off and you seamlessly switch into Art Mode, transforming The Frame into a unique work of art that enriches your living space. The Frame with Walnut Customizable Frame Scott Ramsay, Mana Pools Bee-Eaters (2015) Curated art for your inspiration. Destined to expand your horizons, The Frame’s Art Mode showcases selections of museum-quality artwork professionally curated for you in the exclusive Samsung Collection and online Art Store. Or use My Collection Art Mode TV Mode to display cherished photos of special moments with family and friends. The perfect mode for any mood, Art Mode introduces TV with a sense of your own inimitable style and a knack for enhancing any décor. The Frame, Designed for your space. 2 The Frame 3 The Frame grants you exclusive access to 100 remarkable artworks across 10 categories from 37 renowned artists from the four corners of the world. -

Cairns Part E the Rainforest City Cairns Master Plan City Centre

CAIRNS PART E THE RAINFOREST CITY CAIRNS MASTER PLAN CITY CENTRE CAIRNS PART E THE RAINFOREST CITY CAIRNS MASTER PLAN CITY CENTRE August 2014 - Cairns Regional Council 119-145 Spence Street - PO Box 359 - Cairns - QLD 4870 Ph: (07)4044 3044 F: (07)4044 3022 E: [email protected] This document is available on the Cairns Regional Council website: www.cairns.qld.gov.au Acknowledgements This document would not have been possible without the collaborative efforts of a number of people and organisations. Cairns Regional Council would like to thank all contributors for their involvement, passion and valuable contributions to this section of the master plan. We would particularly like to thank Architectus for allowing us to use their material and imagery; and acknowledge their valuable contribution to the preparation of this document. References Cairns City Centre Master Plan Report October 2011 (Architectus) The Project Team includes the following Council officers: Brett Spencer Manager Parks and Leisure Helius Visser Manager Infrastructure Management Malcolm Robertson Manager Inner City Facilities Debbie Wellington Team Leader Strategic Planning Jez Clark Senior Landscape Architect Claire Burton Landscape Architect C CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION............................................ 10 1.1 What is the purpose of this document? ...................................10 1.2 What area does this document cover? ....................................10 1.3 Who will use this document?.....................................................12 1.4 -

Download Download

Special Issue: Rethinking Affordance Once Again, the Doorknob: Media Theory Vol. 3 | No. 1 | 49-72 © The Author(s) 2019 Affordance, Forgiveness, and CC-BY-NC-ND http://mediatheoryjournal.org/ Ambiguity in Human-Computer Interaction and Human-Robot Interaction OLIA LIALINA Merz Akademie, Stuttgart, Germany Abstract Based on the author‟s keynote lecture at the 2018 „Rethinking Affordance‟ symposium (Stuttgart, Germany), this essay offers a comprehensive survey of the tensions between J.J. Gibson‟s and Don Norman‟s perspectives on the concept of affordance, and formulates an incisive critique of how Norman reconfigured Gibson‟s initial theory. The essay‟s key arguments are triangulated in a critical dialogue between design practices, affordance theory, and a critical reading of design pedagogy. Drawing on her own practice as a pioneering net artist and digital folklore researcher, the author moves from early internet design practices through human-computer interaction and user experience design towards a speculative consideration of the affordances of human- robotic interaction. Keywords AI, Affordance, Interface Design, UX Introduction This essay aims to rethink the concept of affordance through a triangulated analysis of correspondence with design practitioners, critical re-readings of canonical texts, and reflexive engagement with my own creative and pedagogical practices. As both a net artist and an instructor in the field of digital design, I strive to reflect critically on the medium that I work with, in part by way of exploring and showing its underlying properties. Furthermore, as a web archivist and digital folklore researcher, I am also Media Theory Vol. 3 | No. 1 | 2019 http://mediatheoryjournal.org/ interested in examining how users deal with the worlds that they are thrown into by designers. -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

Postinternet, Its Art and (The) New Aesthetic

POSTINTERNET, ITS ART AND (THE) NEW AESTHETIC — A Conceptual Framework for Art Education POSTINTERNET, ITS ART AND (THE) NEW AESTHETIC — A Conceptual Framework for Art Education Elina Nissinen Master of Arts thesis, 30 ECTS Supervisor Kevin Tavin Master’s Program in Art Education Department of Art Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture 2018 Author Elina Nissinen Työn nimi Postinternet, Its Art and (The) New Aesthetic – A Conceptual Framework for Art Education Department Department of Art Degree programme Master’s program in Art Education Year 2018 Number of pages 83 Language English Abstract As one might expect from terms employing the prefixes ‘post’ or ‘new,’ combined with the words ‘internet,’ ‘art,’ and ‘aesthetic,’ postinternet, postinternet art (PIA), and New Aesthetic ((the) NA) are broad and disputable concepts. I started this study because I noticed that these ambiguous, yet widely- discussed terms were hardly acknowledged in art education. This thesis provides a conceptual framework for postinternet, PIA, and (the) (the) NA through a critical review of the literature. Postinternet and (the) NA are notions and phenomena that signpost an era and a condition of unprecedented pace of computation-driven transformations in the human culture. They continue the list of theoretical neologisms indicating the changes brought about by the post-conditions. This thesis establishes that postinternet, PIA, and (the) NA are characterized through their paradoxical relation to time and temporality at conceptual and thematical levels. Obsessed with novelty, these terms attempt to break off from their “previous,” while, starting from their titles, simultaneously anchoring themselves to the past. Postinternet is a notion that describes the inescapable consequences of the intermixing of the online and offline, the omnipresence of the internet. -

A Critical Analysis of Art in the Post- Internet Era Mark Gens

Art Post Internet A Critical Analysis of Art in the Post- Internet Era Mark Gens Te ability of technology to transform art, artist, and art world is not a new concept. Te impact of digital technology and the Internet is yet another dynamic force. What is taking place is a redefnition of authorship, collaboration, and materiality as well as a need for new theoretical and aesthetic notions of how – and where – art is made, viewed, marketed and collected. Tese factors, the ever-expanding World Wide Web, and the pervasive individual ownership of networked devices by most of the privileged world, have ushered in what some refer to as the Post-Internet era. Rather than focusing on the validity of the highly-debated term “Post-Internet” this paper will focus on the developmental shift to which the term refers. Tis shift is an important marker in the movement of ideas and criticality, culture, and context. It is necessary to consider the digital art predecessors to the Post-Internet era. However, the exhibition Art Post-Internet, held at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, China in the spring of 2014, is vital for its well-articulated curatorial perspective. Although the signifcance of the Post-Internet era is still being determined and defned at this moment, Art Post-Internet has made great strides in solidifying its look, methods, context and meaning. Post-Internet is not the end of an era, but rather a poignant marker with lasting potential in the continuum of art history. Mark Gens is a multi-media artist, student, and writer in New York City. -

His Ghosts Must Do My Bidding

Wysing Arts Centre Press Release 21 May 2019 All His Ghosts Must Do My Bidding An ambitious new exhibition celebrating the 30th Anniversary of Wysing Arts Centre 7 July to 25 August Launch: 6 July, 5pm–8pm Gone's for once the old magician With his countenance forbidding; I'm now master, I'm tactician, All his ghosts must do my bidding. Know his incantation, Spells and gestures too; By my mind's creation Wonders shall I do. (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice”, 1779, translation by Paul Dyrsen, 1878) Wysing Arts Centre is delighted to announce an ambitious new exhibition to celebrate its 30th anniversary. Staged across Wysing’s 11-acre rural site, All His Ghosts Must Do My Bidding considers art as magic, artists as magicians, and the studio as a magical site.* The exhibition features new commissions from artists Jill McKnight, Tessa Norton, Pallavi Paul, Imran Perretta and Morgan Quaintance alongside works from Jonathan Baldock, Anna Bunting-Branch, Olivier Castel, Melika Ngombe Kolongo, Shana Moulton, Harold Offeh, Heather Phillipson, Elizabeth Price, Laure Prouvost, Phil Root and Tai Shani. The exhibition begins as an idealistic retelling of “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice”, the tale in which an apprentice uses the master’s magic to cause chaos in the unattended studio, before being caught and punished. In a deliberate act of misreading, All His Ghosts... leaves the tale unfinished, re- interpreting the story as one of liberation. With the ‘forbidding’ master sorcerer gone, and the story’s moralising ending removed, the apprentice is free to experiment, to create and to fail without judgement. -

View PDF for This Newsletter

Newsletter No. 152 September 2012 Price: $5.00 Australasian Systematic Botany Society Newsletter 152 (September 2012) AUSTRALIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY SOCIETY INCORPORATED Council President Vice President Peter Weston Dale Dixon National Herbarium of New South Wales Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney Mrs Macquaries Road Mrs Macquaries Road Sydney, NSW 2000 Sydney, NSW 2000 Australia Australia Tel: (02) 9231 8171 Tel: (02) 9231 8111 Fax: (02) 9241 2797 Fax: (02) 9251 7231 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Treasurer Secretary Frank Zich John Clarkson Australian Tropical Herbarium Dept of National Parks, Recreation, Sport and Racing E2 building, J.C.U. Cairns Campus PO Box 156 PO Box 6811 Mareeba, QLD 4880 Cairns, Qld 4870 Australia Australia Tel: +61 7 4048 4745 Tel: (07) 4059 5014 Fax: +61 7 4092 2366 Fax: (07) 4091 8888 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Councillor (Assistant Secretary - Communications Councillor Ilse Breitwieser Pina Milne Allan Herbarium National Herbarium of Victoria Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd Royal Botanic Gardens PO Box 40 Birdwood Ave Lincoln 7640 South Yarra VIC 3141 New Zealand Australia Tel: +64 3 321 9621 Tel: (03) 9252 2309 Fax: +64 3 321 9998 Fax: (03) 9252 2423 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Other Constitutional Bodies Public Officer Hansjörg Eichler Research Committee Annette Wilson Bill Barker Australian Biological Resources Study Philip Garnock-Jones GPO Box 787 Betsy Jackes Canberra, ACT 2601 Greg Leach Australia Nathalie Nagalingum Christopher Quinn Affiliate Society Chair: Dale Dixon, Vice President Papua New Guinea Botanical Society Grant application closing dates: Hansjörg Eichler Research Fund: ASBS Website on March 14th and September 14th each year. -

The Origins and Exhibition of Rachel Whiteread's 'Untitled (Room 101)'

MA.NOV.Lawrence.pg.proof.corrs:Layout 1 15/10/2010 16:18 Page 736 A substitute for history: the origins and exhibition of Rachel Whiteread’s ‘Untitled (Room 101)’, 2003 by JAMES LAWRENCE IN NOVEMBER 2003, Untitled (Room 101) (Fig.46), by Rachel Whiteread, appeared in the Italian Cast Court at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, where it remained until the following summer. In contrast to the ornate surfaces, elegant contrapposto and fluid modelling of the surrounding casts, the new object presented a rectilinear mass of pockmarked planes and stodgy architectural details. The parenthetical title alludes to the place of final torture in George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) but refers specifically to the real source of the sculpture: Room 101 at Broadcasting House (Fig.45), the headquarters that George Val Myer and Francis James Watson-Hart designed for the British Broadcasting Corporation. A widespread legend held that Room 45. Broadcasting House, 2–22 101 served as Orwell’s office when he worked for the Eastern Portland Place, Service during the Second World War. Early coverage and sub- London W1. sequent discussion of Untitled (Room 101) emphasised this unsub- 1932. Designed by George stantiated literary connection – all the more resonant in 2003, the Val Myer and centenary of Orwell’s birth – and the connotations of authoritar- Francis James ian menace that flow from it.1 This article focuses on less allusive Watson-Hart. (Photograph by aspects, including the circumstances that led to the creation of the Janet Hall, 1995; sculpture; the physical conditions of its origins, form and public RIBA Library display; and the interpretive consequences of those physical traits.