Schmidtjoshua.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4/23/2015 1 •Psychedelics Or Hallucinogens

4/23/2015 Hallucinogens •Psychedelics or This “classic” hallucinogen column The 2 groups below are quite different produce similar effects From the classic hallucinogens Hallucinogens Drugs Stimulating 5HT Receptors Drugs BLOCKING ACH Receptors • aka “psychotomimetics” LSD Nightshade(Datura) Psilocybin Mushrooms Jimsonweed Morning Glory Seeds Atropine Dimethyltryptamine Scopolamine What do the very mixed group of hallucinogens found around the world share in common? •Drugs Resembling NE Drugs BLOCKING Glutamate Receptors •Peyote cactus Phencyclidine (PCP) •Mescaline Ketamine All contain something that resembles a •Methylated amphetamines like MDMA High dose dextromethorphan •Nutmeg neurotransmitter •New synthetic variations (“bath salts”) •5HT-Like Hallucinogens •LSD History • Serotonin • created by Albert Hofmann for Sandoz Pharmaceuticals LSD • was studying vasoconstriction produced by ergot alkaloids LSD • initial exposure was accidental absorption thru skin • so potent ED is in millionths of a gram (25-250 micrograms) & must be delivered on something else (sugar cube, gelatin square, paper) Psilocybin Activate 5HT2 receptors , especially in prefrontal cortex and limbic areas, but is not readily metabolized •Characteristics of LSD & Other “Typical” •Common Effects Hallucinogens • Sensory distortions (color, size, shape, movement), • Autonomic (mostly sympathetic) changes occur first constantly changing (relatively mild) • Vivid closed eye imagery • Sensory/perceptual changes follow • Synesthesia (crossing of senses – e.g. hearing music -

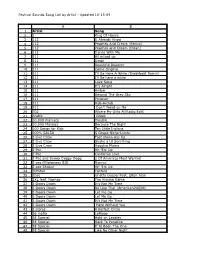

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

The Psytrance Party

THE PSYTRANCE PARTY C. DE LEDESMA M.Phil. 2011 THE PSYTRANCE PARTY CHARLES DE LEDESMA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of East London for the degree of Master of Philosophy August 2011 Abstract In my study, I explore a specific kind of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) event - the psytrance party to highlight the importance of social connectivity and the generation of a modern form of communitas (Turner, 1969, 1982). Since the early 90s psytrance, and a related earlier style, Goa trance, have been understood as hedonist music cultures where participants seek to get into a trance-like state through all night dancing and psychedelic drugs consumption. Authors (Cole and Hannan, 1997; D’Andrea, 2007; Partridge, 2004; St John 2010a and 2010b; Saldanha, 2007) conflate this electronic dance music with spirituality and indigene rituals. In addition, they locate psytrance in a neo-psychedelic countercultural continuum with roots stretching back to the 1960s. Others locate the trance party events, driven by fast, hypnotic, beat-driven, largely instrumental music, as post sub cultural and neo-tribal, representing symbolic resistance to capitalism and neo liberalism. My study is in partial agreement with these readings when applied to genre history, but questions their validity for contemporary practice. The data I collected at and around the 2008 Offworld festival demonstrates that participants found the psytrance experience enjoyable and enriching, despite an apparent lack of overt euphoria, spectacular transgression, or sustained hedonism. I suggest that my work adds to an existing body of literature on psytrance in its exploration of a dance music event as a liminal space, redolent with communitas, but one too which foregrounds mundane features, such as socialising and pleasure. -

Hallucinogen LSD (Live Mix) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Hallucinogen LSD (Live Mix) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: LSD (Live Mix) Country: UK Released: 1995 Style: Goa Trance MP3 version RAR size: 1524 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1155 mb WMA version RAR size: 1510 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 731 Other Formats: APE AUD WMA DTS MIDI MOD ASF Tracklist Hide Credits LSD (Live Mix) A 9:05 Producer, Remix – Hallucinogen LSD (L.S. Doof Remix) B1 6:19 Remix – DoofWritten-By – N. Barber* LSD (Original Version) B2 6:46 Producer [Additional] – Ben KemptonProducer, Mixed By – Hallucinogen Companies, etc. Mixed At – Doof Studios Produced At – Hallucinogen Sound Labs Mixed At – Hallucinogen Sound Labs Phonographic Copyright (p) – Dragonfly Records Copyright (c) – Dragonfly Records Credits Written-By – Simon Posford Notes B1: Mixed at Doof Studios, London. B2: Produced & mixed at Hallucinogen Sound Labs, London. ℗ Dragonfly Records 1995 © Dragonfly Records 1995 Comes in three versions - green, orange or purple label on the A side. Durations extracted from vinyl rip Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year LSD (Live Mix) (12", BFLT 29 Hallucinogen Dragonfly Records BFLT 29 UK 1995 Pur) LSD Remixes (4xFile, TWXDL01 Hallucinogen Twisted Records TWXDL01 UK 2008 MP3, 320) SUB 4804.1 Hallucinogen LSD (CD, Single, Ora) Substance SUB 4804.1 France 1996 LSD (Live Mix) (12", BFLT 29 Hallucinogen Dragonfly Records BFLT 29 UK 1995 Gre) TWST 13RX Hallucinogen LSD (12", Ltd) Twisted Records TWST 13RX Europe 2001 Comments about LSD (Live Mix) - Hallucinogen Nuliax If you like this then you like Goa/Psy Trance. Tired of people whining about how Goa/Psy all sounds the same. -

Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com

Hallucinogens And Dissociative Drug Use And Addiction Introduction Hallucinogens are a diverse group of drugs that cause alterations in perception, thought, or mood. This heterogeneous group has compounds with different chemical structures, different mechanisms of action, and different adverse effects. Despite their description, most hallucinogens do not consistently cause hallucinations. The drugs are more likely to cause changes in mood or in thought than actual hallucinations. Hallucinogenic substances that form naturally have been used worldwide for millennia to induce altered states for religious or spiritual purposes. While these practices still exist, the more common use of hallucinogens today involves the recreational use of synthetic hallucinogens. Hallucinogen And Dissociative Drug Toxicity Hallucinogens comprise a collection of compounds that are used to induce hallucinations or alterations of consciousness. Hallucinogens are drugs that cause alteration of visual, auditory, or tactile perceptions; they are also referred to as a class of drugs that cause alteration of thought and emotion. Hallucinogens disrupt a person’s ability to think and communicate effectively. Hallucinations are defined as false sensations that have no basis in reality: The sensory experience is not actually there. The term “hallucinogen” is slightly misleading because hallucinogens do not consistently cause hallucinations. 1 ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com How hallucinogens cause alterations in a person’s sensory experience is not entirely understood. Hallucinogens work, at least in part, by disrupting communication between neurotransmitter systems throughout the body including those that regulate sleep, hunger, sexual behavior and muscle control. Patients under the influence of hallucinogens may show a wide range of unusual and often sudden, volatile behaviors with the potential to rapidly fluctuate from a relaxed, euphoric state to one of extreme agitation and aggression. -

Public Leadership—Perspectives and Practices

Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Edited by Paul ‘t Hart and John Uhr Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/public_leadership _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Public leadership pespectives and practices [electronic resource] / editors, Paul ‘t Hart, John Uhr. ISBN: 9781921536304 (pbk.) 9781921536311 (pdf) Series: ANZSOG series Subjects: Leadership Political leadership Civic leaders. Community leadership Other Authors/Contributors: Hart, Paul ‘t. Uhr, John, 1951- Dewey Number: 303.34 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher Images comprising the cover graphic used by permission of: Victorian Department of Planning and Community Development Australian Associated Press Australian Broadcasting Corporation Scoop Media Group (www.scoop.co.nz) Cover graphic based on M. C. Escher’s Hand with Reflecting Sphere, 1935 (Lithograph). Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2008 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University. He is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). -

Final Copy 2019 01 31 Charl

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Charles, Christopher Title: Psyculture in Bristol Careers, Projects and Strategies in Digital Music-Making General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Psyculture in Bristol: Careers, Projects, and Strategies in Digital Music-Making Christopher Charles A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of Ph. D. -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

2019 Contribution Refund Summary for Political Party Units Democratic

2019 Contribution Refund Summary for Political Party Units Note: Contributions from a married couple filing jointly are reported as one contribution Party Units Contribution Number Refund Democratic Farmer Labor Party 1st Senate District DFL 5 $450.00 2nd Congressional District DFL 16 $696.28 3rd Congressional District DFL 6 $435.00 5B House District DFL 7 $360.00 5th Congressional District DFL 1 $50.00 5th Senate District DFL 1 $40.00 6th Congressional District DFL 9 $621.42 6th Senate District DFL 2 $150.00 8th Congressional District DFL 1 $100.00 8th Senate District DFL 4 $250.00 9th Senate District DFL 1 $50.00 10th Senate District DFL 1 $50.00 11A House District DFL 1 $50.00 11th Senate District DFL 1 $50.00 12th Senate District DFL 2 $200.00 13th Senate District DFL 17 $1,266.67 14th Senate District DFL 9 $620.00 16th Senate District DFL 36 $2,534.98 19th Senate District DFL 2 $100.00 20th Senate District DFL 7 $350.00 22nd Senate District DFL 3 $200.00 Party Units Contribution Number Refund 25B House District DFL (Olmsted-25) 64 $4,092.75 25th Senate District DFL 4 $200.00 26th Senate District DFL 1 $100.00 29th Senate District DFL 25 $1,920.00 30th Senate District DFL 1 $50.00 31st Senate District DFL 4 $300.00 32nd Senate District DFL 27 $1,900.00 33rd Senate District DFL 43 $3,070.00 34th Senate District DFL 74 $5,310.00 35th Senate District DFL 17 $1,301.30 36th Senate District DFL 2 $150.00 37th Senate District DFL 1 $100.00 38th Senate District DFL 11 $730.00 39th Senate District DFL 14 $1,185.00 40th Senate District DFL -

The BG News March 5, 1998

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 3-5-1998 The BG News March 5, 1998 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News March 5, 1998" (1998). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6302. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6302 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Story Idea? MEN'S BASKETBALL TODAY MAC CHAMPIONSHIP NATION • 4 " you have a news tip or have an idea tor 6 story, call us between noon and 7 p.m. Miami 77 A study says minorities wait longer High: 39 372-6966 Eastern Michigan . .92 for liver transplants Low: 21 • * * • • THURSDAY March 5,1998 • * • Volume 84, Issue 111 Bowling Green, Ohio News • • * • * "An independent student voice serving Bowling Green since 1920' Hartman testifies in trial Crash □ Jack Hartman tesified the University, but he was never called for an interview or even today he thought the seriously considered for the posi- Administration journalism department tion. Instead, it was given to would not consider him Debbie Owens because of her said. skin color, he said. Hartman maintains even if he for a position because Nancy Brendlinger, current would have known the position he is a white male. chairwoman of the department of was considered to be entry level, Journalism and member of the he still would have applied in an search committee for the posi- attempt to make the department tion, agrees that Hartman was upgrade the position rank and By DARLA WARNOCK never a serious candidate. -

Download Brochure

Name: Niraj Singh ACOUSTAMIND Hometown: Mumbai Genre: Electronic Dance Music: Psytrance, Dark Progressive Likes (Facebook): 1270 likes About: Acoustamind - is Niraj Singh who is born and bred from Bombay, India. Niraj got acquainted with disc joking at a very tender age of 16. In his Djing journey, he was hit by the psychedelic music wave in 2005 which gave birth to his psychedelic project “Psyboy Original” under which he performed in several events and festivals throughout India. Completed his “Audio Engineering” from the prestigious SAE institute in the year 2012 to deepen his understanding of music production and is currently pursuing Acoustical instruments. He spends majority time of the day in his studio (Rabbit Hole Soundlab), producing music which consists of dark and harmonic atmospheres, deep and powerful bass lines, psychedelic melodies and synthesized rhythms. His music is a smooth blend of familiar Sounds from the nature and unheard Alienated sounds. “Acoustamind” as a project believes and focuses on working with collaboration with various artists like Karran, Shishiva, etc to produce music with cross collaboration of creative ideologies. Niraj has shared the stage with many senior artists of the dark and forest psychedelic trance genre on numnerous occasions in Goa and other parts of India. Acoustamind’s objective is to spread UNBOUNDED FRESH BREATHTAKING AND BRAIN TRANSFORMING ELECTROMAGNETIC WAVES with a humble smile through SOUNDCARPETS MELTED WITH PHAT KICKS AND ULTRAUEBERROLLING GROOVY BASSLINES and wishes to travel the world. http://bhooteshwara.com/artist/acoustamind/ http://soundcloud.com/…/acoustamind-vs-kosmic-baba-bad-robot Name: Ovnimoon records ALPHATRANCE Hometown: Toulouse, France Genre: Psychedelic trance, Progressive trance Psytrance, Trance Likes(Facebook): 10,588 About: Dj Alphatrance (Ovnimoon Records) is DJ who is spiritually enlightened by Buddhism. -

1 : Daniel Kandi & Martijn Stegerhoek

1 : Daniel Kandi & Martijn Stegerhoek - Australia (Original Mix) 2 : guy mearns - sunbeam (original mix) 3 : Close Horizon(Giuseppe Ottaviani Mix) - Thomas Bronzwaer 4 : Akira Kayos and Firestorm - Reflections (Original) 5 : Dave 202 pres. Powerface - Abyss 6 : Nitrous Oxide - Orient Express 7 : Never Alone(Onova Remix)-Sebastian Brandt P. Guised 8 : Salida del Sol (Alternative Mix) - N2O 9 : ehren stowers - a40 (six senses remix) 10 : thomas bronzwaer - look ahead (original mix) 11 : The Path (Neal Scarborough Remix) - Andy Tau 12 : Andy Blueman - Everlasting (Original Mix) 13 : Venus - Darren Tate 14 : Torrent - Dave 202 vs. Sean Tyas 15 : Temple One - Forever Searching (Original Mix) 16 : Spirits (Daniel Kandi Remix) - Alex morph 17 : Tallavs Tyas Heart To Heart - Sean Tyas 18 : Inspiration 19 : Sa ku Ra (Ace Closer Mix) - DJ TEN 20 : Konzert - Remo-con 21 : PROTOTYPE - Remo-con 22 : Team Face Anthem - Jeff Mills 23 : ? 24 : Giudecca (Remo-con Remix) 25 : Forerunner - Ishino Takkyu 26 : Yomanda & DJ Uto - Got The Chance 27 : CHICANE - Offshore (Kitch 'n Sync Global 2009 Mix) 28 : Avalon 69 - Another Chance (Petibonum Remix) 29 : Sophie Ellis Bextor - Take Me Home 30 : barthez - on the move 31 : HEY DJ (DJ NIKK HARDHOUSE MIX) 32 : Dj Silviu vs. Zalabany - Dearly Beloved 33 : chicane - offshore 34 : Alchemist Project - City of Angels (HardTrance Mix) 35 : Samara - Verano (Fast Distance Uplifting Mix) http://keephd.com/ http://www.video2mp3.net Halo 2 Soundtrack - Halo Theme Mjolnir Mix declub - i believe ////// wonderful Dinka (trance artist) DJ Tatana hard trance ffx2 - real emotion CHECK showtek - electronic stereophonic (feat. MC DV8) Euphoria Hard Dance Awards 2010 Check Gammer & Klubfiller - Ordinary World (Damzen's Classix Remix) Seal - Kiss From A Rose Alive - Josh Gabriel [HQ] Vincent De Moor - Fly Away (Vocal Mix) Vincent De Moor - Fly Away (Cosmic Gate Remix) Serge Devant feat.