The Journal of the Viola Da Gamba Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: a Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras

Texas Music Education Research, 2012 V. D. Baker Edited by Mary Ellen Cavitt, Texas State University—San Marcos Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: A Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras Vicki D. Baker Texas Woman’s University The violin, viola, cello, and double bass have fluctuated in both their gender acceptability and association through the centuries. This can partially be attributed to the historical background of women’s involvement in music. Both church and society rigidly enforced rules regarding women’s participation in instrumental music performance during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In the 1700s, Antonio Vivaldi established an all-female string orchestra and composed music for their performance. In the early 1800s, women were not allowed to perform in public and were severely limited in their musical training. Towards the end of the 19th century, it became more acceptable for women to study violin and cello, but they were forbidden to play in professional orchestras. Societal beliefs and conventions regarding the female body and allure were an additional obstacle to women as orchestral musicians, due to trepidation about their physiological strength and the view that some instruments were “unsightly for women to play, either because their presence interferes with men’s enjoyment of the female face or body, or because a playing position is judged to be indecorous” (Doubleday, 2008, p. 18). In Victorian England, female cellists were required to play in problematic “side-saddle” positions to prevent placing their instrument between opened legs (Cowling, 1983). The piano, harp, and guitar were deemed to be the only suitable feminine instruments in North America during the 19th Century in that they could be used to accompany ones singing and “required no facial exertions or body movements that interfered with the portrait of grace the lady musician was to emanate” (Tick, 1987, p. -

The Comte De St. Germain

THE COMTE DE ST. GERMAIN The Secret of kings: A Monograph By Isabel Cooper-Oakley Milano, G. Sulli-Rao [1912] p. v CONTENTS CHAPTER I. Mystic and Philosopher 1 The theories of his birth--High connections--The friend of kings and princes-- Various titles--Supposed Prince Ragoczy--Historic traces--At the Court at Anspach--Friend of the Orloffs--Moral character given by Prince Charles of Hesse. CHAPTER II. His Travels and Knowledge 25 The Comte de St. Germain at Venice in 1710 and the Countess de Georgy--Letter to the British Museum in 1733 from the Hague--From 1737 to 1742 in Persia--In England in 1745--In Vienna in 1746--In 1755 in India--In 1757 comes to Paris--In 1760 at The Hague--In St. Petersburg in 1762--In Brussels in 1763--Starting new experiments in manufactories--In 1760 in Venice--News from an Italian Newspaper for 1770--M. de St. Germain at Leghorn--In Paris again in 1774--At Triesdorf in 1776--At Leipzig in 1777--Testimony of high character by contemporary writers. p. vi CHAPTER III. PAGE The Coming Danger 53 Madame d’Adhémar and the Comte de St. Germain--His sudden appearance in Paris--Interview with the Countess--Warnings of approaching danger to the Royal Family--Desires to see the King and the Queen--Important note by the Countess d’Adhémar relative to the various times she saw the Comte de St. Germain after his supposed death--Last date 1822. CHAPTER IV. Tragical Prophecies 74 Continuation of the Memoirs of Madame d’Adhémar--Marie Antoinette receives M. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Vol34-1997-1.Pdf

- ---~ - - - - -- - -- -- JOURNAL OF THE VIOLA DA GAMBA SOCIETY OF AMERICA Volume 34 1997 EDITOR: Caroline Cunningham SENIOR EDITOR: Jean Seiler CONSULTING EDITOR: F. Cunningham, Jr. REVIEW EDITOR: Stuart G. Cheney EDITORIAL BOARD Richard Cbarteris Gordon Sandford MaryCyr Richard Taruskin Roland Hutchinson Frank Traficante Thomas G. MacCracken Ian Woodfield CONTENTS Viola cia Gamba Society of America ................. 3 Editorial Note . 4 Interview with Sydney Beck .................. Alison Fowle 5 Gender, Class, and Eighteenth-Centwy French Music: Barthelemy de Caix's Six Sonatas for Two Unaccompanied Pardessus de Viole, Part II ..... Tina Chancey 16 Ornamentation in English Lyra Viol Music, Part I: Slurs, Juts, Thumps, and Other "Graces" for the Bow ................................. Mary Cyr 48 The Archetype of Johann Sebastian Bach's Chorale Setting "Nun Komm, der Heiden Heiland" (BWV 660): A Composition with Viola cia Gamba? - R. Bruggaier ..... trans. Roland Hutchinson 67 Recent Research on the Viol ................. Ian Woodfield 75 Reviews Jeffery Kite-Powell, ed., A Performer's Guide to Renaissance Music . .......... Russell E. Murray, Jr. 77 Sterling Scott Jones, The Lira da Braccio ....... Herbert Myers 84 Grace Feldman, The Golden Viol: Method VIOLA DA GAMBA SOCIETY OF AMERICA for the Bass Viola da Gamba, vols. 3 and 4 ...... Alice Robbins 89 253 East Delaware, Apt. 12F Andreas Lidl, Three Sonatas for viola da Chicago, IL 60611 gamba and violoncello, ed. Donald Beecher ..... Brent Wissick 93 [email protected] John Ward, The Italian Madrigal Fantasies " http://www.enteract.com/-vdgsa ofFive Parts, ed. George Hunter ............ Patrice Connelly 98 Contributor Profiles. .. 103 The Viola da Gamba Society of America is a not-for-profit national I organization dedicated to the support of activities relating to the viola •••••• da gamba in the United States and abroad. -

Color in Your Own Cello! Worksheet 1

Color in your own Cello! Worksheet 1 Circle the answer! This instrument is the: Violin Viola Cello Bass Which way is this instrument played? On the shoulder On the ground Is this instrument bigger or smaller than the violin? Bigger Smaller BONUS: In the video, Will said when musicians use their fingers to pluck the strings instead of using a bow, it is called: Piano Pizazz Pizzicato Potato Worksheet 2 ALL ABOUT THE CELLO Below are a Violin, Viola, Cello, and Bass. Circle the Cello! How did you know this was the Cello? In his video, Will talked about a smooth, connected style of playing when he played the melody in The Swan. What is this style with long, flowing notes called? When musicians pluck the strings on their instrument, does it make the sounds very short or very long? What is it called when musicians pluck the strings? What does the Cello sound like to you? How does that sound make you feel? Use the back of this sheet to write or draw what the sound of the Cello makes you think of! Worksheet 1 - ANSWERS Circle the answer! This instrument is the: Violin Viola Cello Bass Which way is this instrument played? On the shoulder On the ground Is this instrument bigger or smaller than the violin? Bigger Smaller BONUS: In the video, Will said when musicians use their fingers to pluck the strings instead of using a bow, it is called: Piano Pizazz Pizzicato Potato Worksheet 2 - ANSWERS ALL ABOUT THE CELLO Below are a violin, viola, cello, and bass. -

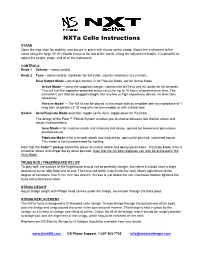

Nxta Cello Instructions STAND Open the Legs Wide for Stability, and Secure in Place with Thumb Screw Clamp

NXTa Cello Instructions STAND Open the legs wide for stability, and secure in place with thumb screw clamp. Mount the instrument to the stand using the large (5/16”) thumb screw at the top of the stand. Using the adjustment knobs, it is possible to adjust the height, angle, and tilt of the instrument. CONTROLS Knob 1 Volume – rotary control Knob 2 Tone – rotary control, clockwise for full treble, counter-clockwise to cut treble. Dual Output Mode – push-pull control, in for Passive Mode, out for Active Mode. Active Mode – Using the supplied charger, connect the NXTa to any AC outlet for 60 seconds. This will fuel the capacitor-powered active circuit for up to 16 hours of performance time. The instrument can then be plugged straight into any low or high impedance device, no direct box necessary. Passive Mode* – The NXTa can be played in this mode with an amplifier with an impedance of 1 meg ohm or greater (3-10 meg ohm recommended) or with a direct box. Switch Arco/Pizzicato Mode selection, toggle up for Arco, toggle down for Pizzicato The design of the Polar™ Pickup System enables you to choose between two distinct attack and decay characteristics: Arco Mode is for massive attack and relatively fast decay, optimal for bowed and percussive plucked sound. Pizzicato Mode is for a smooth attack and long decay, optimal for plucked, sustained sound. This mode is not recommended for bowing. Note that the Polar™ pickup allows the player to control attack and decay parameters. Pizzicato Mode is for a smoother attack and longer decay when plucked. -

Musica Britannica

T69 (2021) MUSICA BRITANNICA A NATIONAL COLLECTION OF MUSIC Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens c.1750 Stainer & Bell Ltd, Victoria House, 23 Gruneisen Road, London N3 ILS England Telephone : +44 (0) 20 8343 3303 email: [email protected] www.stainer.co.uk MUSICA BRITANNICA A NATIONAL COLLECTION OF MUSIC Musica Britannica, founded in 1951 as a national record of the British contribution to music, is today recognised as one of the world’s outstanding library collections, with an unrivalled range and authority making it an indispensable resource both for performers and scholars. This catalogue provides a full listing of volumes with a brief description of contents. Full lists of contents can be obtained by quoting the CON or ASK sheet number given. Where performing material is shown as available for rental full details are given in our Rental Catalogue (T66) which may be obtained by contacting our Hire Library Manager. This catalogue is also available online at www.stainer.co.uk. Many of the Chamber Music volumes have performing parts available separately and you will find these listed in the section at the end of this catalogue. This section also lists other offprints and popular performing editions available for sale. If you do not see what you require listed in this section we can also offer authorised photocopies of any individual items published in the series through our ‘Made- to-Order’ service. Our Archive Department will be pleased to help with enquiries and requests. In addition, choirs now have the opportunity to purchase individual choral titles from selected volumes of the series as Adobe Acrobat PDF files via the Stainer & Bell website. -

The Journal of the Viola Da Gamba Society

The Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society Text has been scanned with OCR and is therefore searchable. The format on screen does not conform with the printed Chelys. The original page numbers have been inserted within square brackets: e.g. [23]. Where necessary footnotes here run in sequence through the whole article rather than page by page and replace endnotes. The pages labelled ‘The Viola da Gamba Society Provisional Index of Viol Music’ in some early volumes are omitted here since they are up-dated as necessary as The Viola da Gamba Society Thematic Index of Music for Viols, ed. Gordon Dodd and Andrew Ashbee, 1982-, available on-line at www.vdgs.org.uk or on CD-ROM. Each item has been bookmarked: go to the ‘bookmark’ tab on the left. To avoid problems with copyright, some photographs have been omitted. Contents of Volume 12 (1983) Editorial Chelys, vol. 12 (1983), p. 2 John Harper article 1 The Distribution of the Consort Music of Orlando Gibbons in Seventeenth-Century Sources Chelys, vol. 12 (1983), pp. 5-18 John M. Jennings article 2 Thomas Lupo Revisited - Is Key the Key to hisLater Music Chelys, vol. 12 (1983), pp. 19-22 Lynn Hulse article 3 John Hingeston Chelys, vol. 12 (1983), pp. 23-42 Gordon Dodd article 4 Tablature Without Tears? Chelys, vol. 12 (1983), pp. 43-46 Hazelle Miloradovitch article 5 Eighteenth-Century Manuscript Transcriptions for Viols of Music by Corelli & Marais in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris: Sonatas and ‘Pièces de Viole’ Chelys, vol. 12 (1983), pp. 47-73 Reviews Clifford Bartlett Orlando Gibbons: new publications of the consort music review 1 Gordon Dodd John Coprario: ‘The Six-part Consorts and Madrigals review 2 Gordon Dodd Richard Charteris: ‘A Catalogue of the printed Book on Music, Printed Music and Music Manuscripts in Archbishop Marsh’s Library, Dublin’ review 3 [extract on] Thomas Gainsborough R.A. -

Crossing Cultural, National, and Racial Boundaries: Portraits of Diplomats and the Pre-Colonial French-Cochinchinese Exchange, 1787-1863

CROSSING CULTURAL, NATIONAL, AND RACIAL BOUNDARIES: PORTRAITS OF DIPLOMATS AND THE PRE-COLONIAL FRENCH-COCHINCHINESE EXCHANGE, 1787-1863 Ashley Bruckbauer A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Mary D. Sheriff Lyneise Williams Wei-Cheng Lin © 2013 Ashley Bruckbauer ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ASHLEY BRUCKBAUER: Crossing Cultural, National, and Racial Boundaries: Portraits of Diplomats and the pre-colonial French-Cochinchinese Exchange, 1787-1863 (Under the direction of Dr. Mary D. Sheriff) In this thesis, I examine portraits of diplomatic figures produced between two official embassies from Cochinchina to France in 1787 and 1863 that marked a pre- colonial period of increasing contact and exchange between the two Kingdoms. I demonstrate these portraits’ departure from earlier works of diplomatic portraiture and French depictions of foreigners through a close visual analysis of their presentation of the sitters. The images foreground the French and Cochinchinese diplomats crossing cultural boundaries of costume and customs, national boundaries of loyalty, and racial boundaries of blood. By depicting these individuals as mixed or hybrid, I argue that the works both negotiated and complicated eighteenth- and nineteenth-century divides between “French” and “foreign.” The portraits’ shifting form and function reveal France’s vacillating attitudes towards and ambivalent foreign policies regarding pre-colonial Cochinchina, which were based on an evolving French imagining of this little-known “Other” within the frame of French Empire. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the support and guidance of several individuals. -

The French Revolution 0

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION 0- THE FRENCH REVOLUTION HIPPOLYTE TAINE 0- Translated by John Durand VOLUME II LIBERTY FUND Indianapolis This book is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to encourage study ofthe ideal ofa society offree and responsible individuals. The cuneiform inscription that serves as our logo and as the design motif for our endpapers is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state ofLagash. ᭧ 2002 Liberty Fund, Inc. All rights reserved. The French Revolution is a translation of La Re´volution, which is the second part ofTaine’s Origines de la France contemporaine. Printed in the United States ofAmerica 02 03 04 05 06 C 54321 02 03 04 05 06 P 54321 Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taine, Hippolyte, 1828–1893. [Origines de la France contemporaine. English. Selections] The French Revolution / Hippolyte Taine; translated by John Durand. p. cm. “The French Revolution is a translation ofLa Re´volution, which is the second part ofTaine’s Origines de la France contemporaine”—T.p. verso. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-86597-126-9 (alk. paper) ISBN 0-86597-127-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. France—History—Revolution, 1789–1799. I. Title. DC148.T35 2002 944.04—dc21 2002016023 ISBN 0-86597-126-9 (set: hc.) ISBN 0-86597-127-7 (set: pb.) ISBN 0-86597-363-6 (v. 1: hc.) ISBN 0-86597-366-0 (v. 1: pb.) ISBN 0-86597-364-4 (v. -

The Duchess of Berry and the Court of Charles X

The Duchess Of Berry And The Court Of Charles X By Imbert De Saint-Amand THE DUCHESS OF BERRY AND THE COURT OF CHARLES X I THE ACCESSION OF CHARLES X Thursday, the 16th of September, 1824, at the moment when Louis XVIII. was breathing his last in his chamber of the Chateau des Tuileries, the courtiers were gathered in the Gallery of Diana. It was four o'clock in the morning. The Duke and the Duchess of Angouleme, the Duchess of Berry, the Duke and the Duchess of Orleans, the Bishop of Hermopolis, and the physicians were in the chamber of the dying man. When the King had given up the ghost, the Duke of Angouleme, who became Dauphin, threw himself at the feet of his father, who became King, and kissed his hand with respectful tenderness. The princes and princesses followed this example, and he who bore thenceforward the title of Charles X., sobbing, embraced them all. They knelt about the bed. The De Profundis was recited. Then the new King sprinkled holy water on the body of his brother and kissed the icy hand. An instant later M. de Blacas, opening the door of the Gallery of Diana, called out: "Gentlemen, the King!" And Charles X. appeared. Let us listen to the Duchess of Orleans. "At these words, in the twinkling of an eye, all the crowd of courtiers deserted the Gallery to surround and follow the new King. It was like a torrent. We were borne along by it, and only at the door of the Hall of the Throne, my husband bethought himself that we no longer had aught to do there.