Two Points for Kissing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Tonnage Rating" Discarded Packard

PHOMIXEVT WRITERS CORIBrTE. HERLD SrORTS LEID AJLL. lot-'- sport pcpe carrooiUt 1 Tad Dorian ad o' i latest news of boxing, wrestling- foo- bfJ-- i a. golf bowling JLsS J, writer :san rare and Er i'1 ter all tennis and othar athletic mBEBBSm and dopester T S. Andrews boxing critic Frars s columns of The Herald. Full JJ&CjrJLJLJP w.orJ-Jac- k ound the sport in SJ. i9 Otiimt-- t one of the greatest amateur fcol'ers of the u re serWce on all biff game and match. Re- - PASO Velock and 'Gravy baseball and boxing wri'ers r in ormation on sporting" events given special OUT-DOO- leading to The Herald Sports Department n by Sports Information Bureau. Telephone 2020 BOXING BOWLING BASKETBALL BASEBALL GOLF TENNIS IfR LIFE are contributors Army And City League Teams Organize; Featherweight Champ Loses Bout - - " .. - p A T TT TT 1 Tt ITSt SIX TFMI1 Wll 1 Carpentier Is Crafty And Texas League Fans Will Australia Has ma tor title VALGER DEFEATS UIA ILnlilu HILL ixrsn o , ua n,--, See Some Heavy Hitting nonorsmuewnawaras wno COMPOSE FAS s irio S Kol-- r chip j. TJOUSTQN, Tex, Pen. 2. FandonVs continned. "but by no means a --li-lO l tea tre&iiiiimrrrtf- ForChampionJackDempsey II plea for more hitting naa been majority. Cy Young, Matty and Carpentler's bonnet. He'll be think- heard at last by the Texas as ap Rocker, of the pitching Zfi&t5tM05H.the top of the lightweight ing a mile a minute when he meets well as the major leagues school that hna passed along In America and a match McAuliffe Dempeey, and fighting the same way. -

Georges Carpentier Sur La Riviera En Février 1912, Stéphane Hadjeras

Georges Carpentier sur la Riviera Février 1912 Stéphane Hadjeras Doctorant en histoire Contemporaine - Université de Franche Comté A la fin de l’année 1911, Georges Carpentier n’avait même pas 18 ans et pourtant sa carrière de pugiliste semblait avoir pris un tournant majeur pour au moins deux raisons. D’abord le 23 octobre, devant un public londonien médusé, il devint, en infligeant au King’s Hall une sévère défaite au britannique Young Joseph, le premier champion d’Europe français. Puis, le 13 décembre, au Cirque de Paris, à la grande surprise des journalistes sportifs et autres admirateurs du noble art, il battit aux points le célèbre « fighter » américain, ancien champion du monde des poids welters, Harry Lewis. Accueilli, en véritable héros à son retour de Londres, par plus de 3000 personnes à la Gare du Nord, plébiscité par la presse sportive après son triomphe sur l’américain, ovationné par un Paris mondain de plus en plus féru de boxe, Georges Carpentier fut en passe de devenir en ce début d’année 1912 l’idole de toute une nation. Ainsi, l’annonce de son combat contre le britannique Jim Sullivan, le 29 février, à Monte Carlo, pour le titre de champion d’Europe des poids moyens, apparut de plus en plus comme une confirmation de l’inéluctable ascension du « petit prodige »1 vers le titre mondial. Monte Carlo. L’évocation de ce lieu provoqua chez le champion un début d’évasion : « La Cote d’Azur, la mer bleue, le ciel plus bleu encore, les palmiers, les arbres avec des oranges ! J’avais vu des affiches et des prospectus. -

January 2010 Newsletter

January 2010 – Volume 2, Issue 1 THE DRAGON’S LAIR NEWSLETTER OF THE IRON DRAGON KUNG FU AND KICKBOXING CLUB 91 STATION STREET, UNIT 8, AJAX, ONTARIO L1S 3H2 JANUARY 2010 VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 (905) 427-7370 / [email protected] / www.iron-dragon.ca COMMENTARY HAPPY NEW YEAR! 2010 here we come! Those of you who have heeded Ol’ Sifu’s advice have burst out of the starting blocks to start 2010 up and running. For those brethren who did not and are now horizontal on the couch, recovering from their New Years Eve hangover…..IT IS STILL NOT TOO LATE! LOL! Get ye’ over to yonder Iron Dragon Kung Fu and Kickboxing Club as soon as you can so that you will be ahead of the pack for 2010! CHANGES IN CLASS FORMATS FOR 2010! I am tinkering with the format for Saturdays Circuit Training and MMA class. From now on the new Chinese Wrestling Moves will be introduced on Thursday nights and then the reinforcement of those moves will be done on Saturday along with Open Grappling and also at the end of every Kung Fu Kickboxing Class till the following Thursday. We will use the Ontario Jiu Jitsu Point System to score Saturdays Open Grappling so we can get used to the point system before 2010 grappling competitions. Chinese Wrestling techniques that are not legal in Jiu Jitsu and Grappling will still be taught because they are effective self defense - we just have to remember what is legal in competition! LOL! The Wednesday classes at 12:00 pm and 8:00 pm have been designated as full equipment training classes. -

My Fighting Life

MY MY FIGHTING LIFE Photo: Hana Studios, Ltd. _/^ My Fighting Life BY GEORGES GARPENTIER (Champion Heavy-wight Boxer of With Eleven Illustrations CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1920 To All British Sportsmen I dedicate this, The Story of My Life. Were I of their own great country, I feel I could have no surer, no warmer, no more lasting place in their friendship CONTENTS CHAPTBX FAGB 1. I BECOME DESCAMPS' PUPIL ... 1 2. To PARIS 21 3. MY PROFESSIONAL CAREER BEGINS . 30 4. I Box IN ENGLAND ..... 47 5. MY FIGHTS WITH LEDOUX, LEWIS, SULLIVAN AND OTHERS ..... 51 6. I MEET THE ILLINOIS THUNDERBOLT . 68 7. MY FIGHTS WITH WELLS AND A SEQUEL . 79 8. FIGHTS IN 1914 99 9. THE GREAT WAR : I BECOME A FLYING MAN 118 10. MILITARY BOXING ..... 133 11. ARRANGING THE BECKETT FIGHT . 141 12. THE GREAT FIGHT 150 13. PSYCHOLOGY AND BOXING . 158 14. How I TRAINED TO MEET BECKETT . 170 15. THE FUTURE OF BOXING : TRAINING HINTS AND SECRETS . .191 16. A CHAPTER ON FRA^OIS DESCAMPS . 199 17. MEN I HAVE FOUGHT .... 225 ILLUSTRATIONS GEORGES CARPENTIER .... Frontispiece FACING PAGE 1. CARPENTIER AT THE AGE OF TWELVE . 10 CARPENTIER AT THE AGE OF THIRTEEN . 10 2. CARPENTIER (WHEN ELEVEN) WITH DESCAMPS . 24 CARPENTIER AND LEDOUX . .24 3. M. DESCAMPS ...... 66 4. CARPENTIER WHEN AN AIRMAN . .180 5. CARPENTIER AT THE AGE OF SEVENTEEN . 168 CARPENTIER TO-DAY . .. .168 6. CARPENTIER IN FIGHTING TRIM . 226 7. M. AND Mme. GEORGES CARPENTIER . 248 MY FIGHTING LIFE CHAPTER I I BECOME DESCAMPS' PUPIL OUTSIDE my home in Paris many thousands of my countrymen shouted and roared and screamed; women tossed nosegays and blew kisses up to my windows. -

This Is a Terrific Book from a True Boxing Man and the Best Account of the Making of a Boxing Legend.” Glenn Mccrory, Sky Sports

“This is a terrific book from a true boxing man and the best account of the making of a boxing legend.” Glenn McCrory, Sky Sports Contents About the author 8 Acknowledgements 9 Foreword 11 Introduction 13 Fight No 1 Emanuele Leo 47 Fight No 2 Paul Butlin 55 Fight No 3 Hrvoje Kisicek 6 3 Fight No 4 Dorian Darch 71 Fight No 5 Hector Avila 77 Fight No 6 Matt Legg 8 5 Fight No 7 Matt Skelton 93 Fight No 8 Konstantin Airich 101 Fight No 9 Denis Bakhtov 10 7 Fight No 10 Michael Sprott 113 Fight No 11 Jason Gavern 11 9 Fight No 12 Raphael Zumbano Love 12 7 Fight No 13 Kevin Johnson 13 3 Fight No 14 Gary Cornish 1 41 Fight No 15 Dillian Whyte 149 Fight No 16 Charles Martin 15 9 Fight No 17 Dominic Breazeale 16 9 Fight No 18 Eric Molina 17 7 Fight No 19 Wladimir Klitschko 185 Fight No 20 Carlos Takam 201 Anthony Joshua Professional Record 215 Index 21 9 Introduction GROWING UP, boxing didn’t interest ‘Femi’. ‘Never watched it,’ said Anthony Oluwafemi Olaseni Joshua, to give him his full name He was too busy climbing things! ‘As a child, I used to get bored a lot,’ Joshua told Sky Sports ‘I remember being bored, always out I’m a real street kid I like to be out exploring, that’s my type of thing Sitting at home on the computer isn’t really what I was brought up doing I was really active, climbing trees, poles and in the woods ’ He also ran fast Joshua reportedly ran 100 metres in 11 seconds when he was 14 years old, had a few training sessions at Callowland Amateur Boxing Club and scored lots of goals on the football pitch One season, he scored -

Walcott in 1 Punch KO 10 ^ Tragedy

A RHH: ms\ ': '•' I" WWI W MB Ike, Sugar, Ez Dethroned; Who's Next? THE OHIO J - •••—g * **^*»— \%:*n High st. 10 Poop**** Walcott In 1 Punch KO ^ PITTSBURGH.—Four tune* previously a challenger but taever a winner, ancient Jersey Joe Walcott rewrote THLZ OHIO M VOL. J. Wa. 7 SATURDAY, JULY 28, 1951 COLUMBUS. OHIO boxing'* Cinder*?! I * Story by ocotriog a one-punch seventh •round kayo over Champion Eaaanrl Charles of Cincinnati before a shocked throng of 30,000 fane here at Forbes INEL field Wednesday night. Thus, the up.iet Mtrinir, be . gun with Ike Williams' de* coming in with a hard right m«*e in the lightweight di- hand. VOL. 3, No. 6 Saturday, July 21, 1951 CoJumbae, Ohio vi-tioii. Sugar Ray Robin- Ex fell forward, rolled aon'a fumbling of the mid over and making a dee- dleweight crown m London perate effort to rise, as Tragedy a week aft*o, w tarried over the count reached nine, Sports Gleanings into the heavyweight divi slumped on his face and sion, mo-rt lucrative of the the year's biggest sports lot, and where thi* crazy story was born. Thc kayo •pin of up.net event** will end was recorded at 55 sec no one dares predict. onds of the seventh round. Turpin Gives Boxing Needed Walcott had been refer That's the fight simply. red to by many as "Often a There were no sensational beat man but never a bride," early round exchanges and and along with the Drornot- the finish came as sudden as ers of Wednesday's fight was the surprise with which Shot In Arm In Beating Ray was being ridiculed, by fans it was received. -

On Modernity, Identity and White-Collar Boxing. Phd

From Rookie to Rocky? On Modernity, Identity and White-Collar Boxing Edward John Wright, BA (Hons), MSc, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. September, 2017 Abstract This thesis is the first sociological examination of white-collar boxing in the UK; a form of the sport particular to late modernity. Given this, the first research question asked is: what is white-collar boxing in this context? Further research questions pertain to social divisions and identity. White- collar boxing originally takes its name from the high social class of its practitioners in the USA, something which is not found in this study. White- collar boxing in and through this research is identified as a practice with a highly misleading title, given that those involved are not primarily from white-collar backgrounds. Rather than signifying the social class of practitioner, white-collar boxing is understood to pertain to a form of the sport in which complete beginners participate in an eight-week boxing course, in order to compete in a publicly-held, full-contact boxing match in a glamorous location in front of a large crowd. It is, thus, a condensed reproduction of the long-term career of the professional boxer, commodified for consumption by others. These courses are understood by those involved to be free in monetary terms, and undertaken to raise money for charity. As is evidenced in this research, neither is straightforwardly the case, and white-collar boxing can, instead, be understood as a philanthrocapitalist arrangement. The study involves ethnographic observation and interviews at a boxing club in the Midlands, as well as public weigh-ins and fight nights, to explore the complex interrelationships amongst class, gender and ethnicity to reveal the negotiation of identity in late modernity. -

Boxing Edition

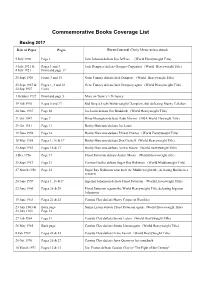

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

Tyson Fury BBC SPOTY Furore Could Have Been Avoided – They Should Have Chosen Anthony Crolla

BBC SPOTY Tyson Fury Furore could have been avoided Item Type Article Authors Randles, David Citation Randles, D. (2015). BBC SPOTY Tyson Fury Furore could have been avoided. Vice Sports. Retrieved from https:// sports.vice.com/en_uk/article/bbc-spoty-tyson-fury-furore- could-have-been-avoided-they-should-have-chosen-anthony- crolla Publisher Vice Sports Download date 30/09/2021 05:17:40 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/618221 Tyson Fury BBC SPOTY furore could have been avoided – they should have chosen Anthony Crolla By David Randles - @davidrandles It will be interesting to see the table plan for the BBC Sports Personality of the Year awards. While steps will be taken to keep Tyson Fury away from Jessica Ennis-Hill, it may also be wise to put Greg Rutherford at the opposite end of the room to the recently crowned heavyweight champion of the world. It was Fury’s sexist comments about Ennis-Hill, combined with his forthright views aligning homosexuality and pedophilia, that riled Rutherford enough for the Olympic long jump champion to withdraw from the SPOTY 2015 running before changing his mind. Joining the chorus of condemnation for Fury are Northern Ireland’s largest gay rights group the Rainbow Project, who this week labeled his comments as ‘extremely callous’ and ‘erroneous’. In response to Fury’s insistence that a woman’s place is ‘in the kitchen or on her back’, feminist group Fight4Equality has blasted the self-titled Gypsy King’s ‘neanderthal worldview’ insisting Fury ‘should not be feted as a role model for young people.’ Both groups will be joined by other LGBT campaigners outside Belfast’s SSE Arena on Sunday evening to picket the BBC, angry that the show will go on despite vocal public opposition to Fury’s involvement. -

Mixed Martial Arts Rules for Amateur Competition Table of Contents 1

MIXED MARTIAL ARTS RULES FOR AMATEUR COMPETITION TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SCOPE Page 2 2. VISION Page 2 3. WHAT IS THE IMMAF Page 2 4. What is the UMMAF Page 3 5. AUTHORITY Page 3 6. DEFINITIONS Page 3 7. AMATEUR STATUS Page 5 8. PROMOTERS & REQUIREMENTS Page 5 9. PROMOTERS INSURANCE Page 7 10. PHYSICIANS AND EMT’S Page 7 11. WEIGN-INS & WEIGHT DIVISIONS Page 8 12. COMPETITORS APPEARANCE& REQUIREMENTS Page 9 13. COMPETITOR’s MEDICAL TESTING Page 10 14. MATCHMAKING APPROVAL Page 11 15. BOUTS, CONTESTS & ROUNDS Page 11 16. SUSPENSIONS AND REST PERIODS Page 12 17. ADMINISTRATION & USE OF DRUGS Page 13 18. JURISDICTION,ROUNDS, STOPPING THE CONTEST Page 13 19. COMPETITOR’s REGISTRATION & EQUIPMENT Page 14 20. COMPETITON AREA Page 16 21. FOULS Page 17 22. FORBIDDEN TECHNIQUES Page 18 23. OFFICIALS Page 18 24. REFEREES Page 19 25. FOUL PROCEDURES Page 21 26. WARNINGS Page 21 27. STOPPING THE CONTEST Page 22 28. JUDGING TYPES OF CONTEST RESULTS Page 22 29. SCORING TECHNIQUES Page 23 30. CHANGE OF DECISION Page 24 31. ANNOUNCING THE RESULTS Page 24 32. PROTESTS Page 25 33. ADDENDUMS Page 26 PROTOCOL FOR COMPETITOR CORNERS ROLE OF THE INSPECTORS MEDICAL HISTORY ANNUAL PHYSICAL OPTHTHALMOLOGIC EXAM PROTOCOL FOR RINGSIDE EMERGENCY PERSONNEL PRE & POST –BOUT MEDICAL EXAM 1 SCOPE: Amateur Mixed Martial Arts [MMA] competition shall provide participants new to the sport of MMA the needed experience required in order to progress through to a possible career within the sport. The sole purpose of Amateur MMA is to provide the safest possible environment for amateur competitors to train and gain the required experience and knowledge under directed pathways allowing them to compete under the confines of the rules set out within this document. -

Myrrh NPR I129 This Newsletter Is Dedicated to the Nucry of Jim

International Boxing Research Organization Myrrh NPR i129 This newsletter is dedicated to the nucry of Jim Jacobs, who was not only a personal friend, but a friend to all boxing his- torians. Goodbye, Jim, I'll miss you. From: Tim Leone As the walrus said, "The time has come to talk of many things". This publication marks the 6th IBRO newsletter which has been printed since John Grasso's departure. I would like to go on record by saying that I have enjoyed every minute. The correspondence and phone conversations I have with various members have been satisfing beyond words. However, as many of you know, the entire financial responsibility has been paid in total by yours truly. The funds which are on deposit from previous membership cues have never been forwarded. Only four have sent any money to cover membership dues. To date, I have spent over $6,000.00 on postage, printing, & envelopes. There have also been a quantity of issues sent to prospective new members, various professional groups, and some newspapers.I have not requested, nor am I asking or expecting any re-embursement. The pleasure has been mine. However; the members have now received all the issues that their dues (sent almost two years ago) paid for. I feel the time is prudent to request new membership dues to off-set future expenses. After speaking with various members, and taking into consideration the post office increase April 1, 1988, a sum of $20.00, although low to the point of barely breaking even, should be asked for. -

WBC International Championships

Dear Don José … I will be missing you and I will never forget how much you did for the world of boxing and for me. Mauro Betti The Committee decided to review each weight class and, when possible, declare some titles vacant. The hope is to avoid the stagnation of activities and, on the contrary, ensure to the boxing community a constant activity and the possibility for other boxers to fight for this prestigious belt. The following situation is now up to WEDNESDAY 9 November 2016: Heavy Dillian WHYTE Jamaica Silver Heavy Andrey Rudenko Ukraine Cruiser Constantin Bejenaru Moldova, based in NY USA Lightheavy Joe Smith Jr. USA … great defence on the line next December. Silver LHweight: Sergey Ekimov Russia Supermiddle Michael Rocky Fielding Great Britain Silver Supermiddle Avni Yildirim Turkey Middle Craig CUNNINGHAM Great Britain Silver Middleweight Marcus Morrison GB Superwelter vacant Sergio Garcia relinquished it Welter Sam EGGINGTON Great Britain Superlight Title vacant Cletus Seldin fighting for the vacant belt. Silver 140 Lbs Aik Shakhnazaryan (Armenia-Russia) Light Sean DODD, GB Successful title defence last October 15 Silver 135 Lbs Dante Jardon México Superfeather Martin Joseph Ward GB Silver 130 Lbs Jhonny Gonzalez México Feather Josh WARRINGTON GB Superbantam Sean DAVIS Great Britain Bantam Ryan BURNETT Northern Ireland Superfly Vacant title bout next Friday in the Philippines. Fly Title vacant Lightfly Vacant title bout next week in the Philippines. Minimum Title vacant Mauro Betti WBC Vice President Chairman of WBC International Championships Committee Member of Ratings Committee WBC Board of Governors Rome, Italy Private Phone +39.06.5124160 [email protected] Skype: mauro.betti This rule is absolutely sacred to the Committee WBC International Heavy weight Dillian WHYTE Jamaica WBC # 13 WBC International Heavy weight SILVER champion Ukraine’s Andryi Rudenko won the vacant WBC International Silver belt at Heavyweight last May 6 in Odessa, Ukraine, when he stopped in seven rounds USA’s Mike MOLLO.