The Bibliographical Variants Between the Last of Us and the Last of Us Remastered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

The First but Hopefully Not the Last: How the Last of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre

The College of Wooster Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2018 The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre Joseph T. Gonzales The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gonzales, Joseph T., "The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre" (2018). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 8219. This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The College of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2018 Joseph T. Gonzales THE FIRST BUT HOPEFULLY NOT THE LAST: HOW THE LAST OF US REDEFINES THE SURVIVAL HORROR VIDEO GAME GENRE by Joseph Gonzales An Independent Study Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Course Requirements for Senior Independent Study: The Department of Communication March 7, 2018 Advisor: Dr. Ahmet Atay ABSTRACT For this study, I applied generic criticism, which looks at how a text subverts and adheres to patterns and formats in its respective genre, to analyze how The Last of Us redefined the survival horror video game genre through its narrative. Although some tropes are present in the game and are necessary to stay tonally consistent to the genre, I argued that much of the focus of the game is shifted from the typical situational horror of the monsters and violence to the overall narrative, effective dialogue, strategic use of cinematic elements, and character development throughout the course of the game. -

La Evolución De La Narrativa En El Videojuego Trabajo Final De Grado

La evolución de la narrativa en el videojuego Trabajo final de grado Curso 2018/2019 Javier M. García González Beneharo Mesa Peña Grado en Periodismo Profesor tutor: Dr. Benigno León Felipe Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y de la Comunicación Trabajo final de grado RESUMEN En este trabajo se pretende mostrar los mecanismos y funcionamientos narrativos dentro de la industria lúdica del videojuego, comentando los primeros títulos que fueron creados y la posterior evolución de la narración de sus historias. Asimismo, se analizarán las particularidades entre las mecánicas del videojuego y cómo estas se ajustan a la narrativa a cada género, señalando cuáles son los más populares, cuáles incurren más en disonancias, juegos de autor, así como aquellos títulos que han sentado precedentes a la hora de crear historias en los videojuegos. Como conclusión final, se tratará de mostrar las particularidades y complejidades de un medio que, si bien es menos longevo que el cine, música o la literatura, genera más beneficio que los anteriores en su conjunto. Por otro lado, aunque en sus inicios el videojuego tuviera unos objetivos más limitados, a lo largo de su evolución se ha acercado al lenguaje literario y cinematográfico, creando así una retroalimentación entre estas tres modalidades artísticas. PALABRAS CLAVE Videojuego, narrativa, ludonarrativa, software, interactividad, transmedia, arte, literatura, cine. ABSTRACT The aim of this work is to show the narrative mechanisms and functions within the video game industry, commenting on the first titles that were created and the subsequent evolution of storytelling. Also, It will analyze the particularities between the mechanics of the game and how they fit the narrative to each genre, indicating which are the most popular, which incur more dissonance, author games, as well as those titles that set precedents to create stories in video games. -

Playstation Games

The Video Game Guy, Booths Corner Farmers Market - Garnet Valley, PA 19060 (302) 897-8115 www.thevideogameguy.com System Game Genre Playstation Games Playstation 007 Racing Racing Playstation 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London Adventure Action & Adventure Playstation 102 Dalmatians Puppies to the Rescue Action & Adventure Playstation 1Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 2Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 3D Baseball Baseball Playstation 3Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 40 Winks Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 2 Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 3 Electrosphere Other Playstation Aces of the Air Other Playstation Action Bass Sports Playstation Action Man Operation EXtreme Action & Adventure Playstation Activision Classics Arcade Playstation Adidas Power Soccer Soccer Playstation Adidas Power Soccer 98 Soccer Playstation Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Iron and Blood RPG Playstation Adventures of Lomax Action & Adventure Playstation Agile Warrior F-111X Action & Adventure Playstation Air Combat Action & Adventure Playstation Air Hockey Sports Playstation Akuji the Heartless Action & Adventure Playstation Aladdin in Nasiras Revenge Action & Adventure Playstation Alexi Lalas International Soccer Soccer Playstation Alien Resurrection Action & Adventure Playstation Alien Trilogy Action & Adventure Playstation Allied General Action & Adventure Playstation All-Star Racing Racing Playstation All-Star Racing 2 Racing Playstation All-Star Slammin D-Ball Sports Playstation Alone In The Dark One Eyed Jack's Revenge Action & Adventure -

Markedness, Gender, and Death in Video Games

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-2-2020 1:00 PM Exquisite Corpses: Markedness, Gender, and Death in Video Games Meghan Blythe Adams, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Boulter, Jonathan, The University of Western Ontario : Faflak, Joel, The University of Western Ontario A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in English © Meghan Blythe Adams 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Meghan Blythe, "Exquisite Corpses: Markedness, Gender, and Death in Video Games" (2020). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7414. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7414 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This dissertation analyzes gendered death animations in video games and the way games thematize death to remarginalize marked characters, including women. This project combines Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s work on the human subjection to death and Georges Bataille’s characterization of sacrifice to explore how death in games stages markedness. Markedness articulates how a culture treats normative identities as unproblematic while marking non-normative identities as deviant. Chapter One characterizes play as a form of death-deferral, which culminates in the spectacle of player-character death. I argue that death in games can facilitate what Hegel calls tarrying with death, embracing our subjection to mortality. -

Uncharted 2: Among Thieves Breaks Away and Flees with 10 Awards During the 13Th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards

Contact: Debby Chen / Wendy Zaas Geri Gordon Miller Rogers & Cowan Academy of Interactive Arts and 310-854-8168 / 310-854-8148 Sciences [email protected] 818-876-0826 x202 [email protected] [email protected] UNCHARTED 2: AMONG THIEVES BREAKS AWAY AND FLEES WITH 10 AWARDS DURING THE 13TH ANNUAL INTERACTIVE ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS LAS VEGAS – February 18, 2010 – Escaping with10 outstanding awards, Uncharted 2: Among Thieves (Sony Computer Entertainment) ran over the competition at the 13th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards®. Hosted by stand-up comedian and video game enthusiast Jay Mohr at the Red Rock Resort in Las Vegas, the evening brought together renowned leaders from the gaming industry to recognize their outstanding achievements and contributions to the space. The 13th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards honored successful game designer and Activision co-founder, David Crane with the AIAS’ first Pioneer Award. Entertainment Software Association (ESA) founder, Douglas Lowenstein was honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award. Gaming legend behind successful titles, Crash Bandicoot and Spyro the Dragon, Mark Cerny, was inducted into the Hall of Fame, one of the organization’s highest honors. “The interactive world continues to grow and move forward every day. While we have seen tremendous advances in the community, I believe this is only the beginning,” said Joseph Olin, president, AIAS. “With the help of the tremendously talented men and women here tonight, we will continue to create games that inspire each other to continue pushing the envelope.” These peer-based awards recognize the outstanding products, talented individuals and development teams that have contributed to the advancement of the multi-billion dollar worldwide entertainment software industry. -

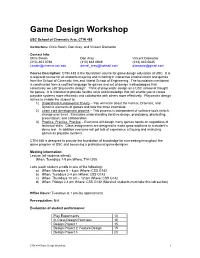

Game Design Workshop

Game Design Workshop USC School of Cinematic Arts, CTIN 488 Instructors: Chris Swain, Dan Arey, and Vincent Diamante Contact Info: Chris Swain Dan Arey Vincent Diamante (310) 403 0798 (310) 663 0949 (213) 840 0645 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Course Description: CTIN 488 is the foundation course for game design education at USC. It is a required course for all students majoring and minoring in interactive entertainment and games from the School of Cinematic Arts and Viterbi School of Engineering. The foundation mentioned is constructed from a codified language for games and set of design methodologies that collectively we call “playcentric design”. Think of playcentric design as a USC school of thought for games. It is intended to provide flexible skills and knowledge that will enable you to create playable systems more efficiently and collaborate with others more effectively. Playcentric design strives to enable the student to: 1) Understand Fundamental Theory – You will learn about the Formal, Dramatic, and Dynamic elements of games and how the three interrelate 2) Learn core development process – This process is independent of software tools (which change over time). It includes understanding iterative design, prototyping, playtesting, presentation, and collaboration 3) Practice, Practice, Practice – Everyone will design many games hands-on regardless of technical skills. Class assignments are designed to make good additions to a student’s demo reel. In addition everyone will get lots of experience critiquing and analyzing games as playable systems. CTIN 488 is designed to provide the foundation of knowledge for succeeding throughout the game program at USC and becoming a professional game designer. -

Universidad De Guadalajara

Universidad de Guadalajara Centro Universitario en Arte, Arquitectura y Diseño Doctorado Interinstitucional en Arte y Cultura Tema de Tesis: En contra de la momificación. Los videojuegos como artefactos de cultura visual contemporánea: la emulación y simulación a nivel circuito, a modo de tácticas de su preservación Tesis que para obtener el grado de Doctor en Arte y Cultura Presenta: Romano Ponce Díaz Director de Tesis: Dr. Jorge Arturo Chamorro Escalante Línea de Generación y Aplicación del Conocimiento: Artes Visuales. Guadalajara, Jalisco, febrero del 2019 1 En contra de la momificación. Los videojuegos como artefactos de cultura visual contemporánea: la emulación y simulación a nivel circuito, a modo de tácticas de su preservación. ©Derechos Reservados 2019 Romano Ponce Díaz [romano.ponce@ alumnos.udg.mx] 2 ÍNDICE DE ILUSTRACIONES. 8 ÍNDICE DE TABLAS. 8 1.1 PRESENTACIÓN 9 1.2 AGRADECIMIENTOS 11 1.3 RESUMEN 13 1.4 ABSTRACT 14 2 PRIMER NODO: EXPOSICIÓN. 16 2.1.1 CAPÍTULO 2. EL PROBLEMA PREFIGURADO: 19 2.2 OTRO EPÍLOGO A MANERA DE PRÓLOGO. 19 2.3 EL RELATO COMO PRESERVADOR DEL TESTIMONIO DE LA CULTURA. 20 2.4 LA MEMORIA PROSTÉTICA, SU RELACIÓN CON LOS OBJETOS, Y, LA NATURALEZA FINITA 27 2.4.1 CINEMATOGRAFÍA, EXPLOSIONES Y FILMES PERDIDOS 29 2.4.2 LOS VIDEOJUEGOS Y LAS FORMAS DE MIRAR AL MUNDO 33 2.4.3 VIDEOJUEGOS, IDEOLOGÍA, VISUALIDAD Y ARTE: 35 2.4.4 LA ESTRUCTURA DE LA OBSOLESCENCIA Y EL MALESTAR DE LA CULTURA 46 2.5 ANTES DE QUE CAIGA EN EL OLVIDO: UNA HIPÓTESIS 49 2.5.1 SOBRE LOS OBJETIVOS, ALCANCES, Y LA MORFOLOGÍA DEL TEXTO 51 3 CAPÍTULO 3. -

Billy Harper Animation Director at Sucker Punch Productions [email protected]

Billy Harper Animation Director at Sucker Punch Productions [email protected] Summary My professional experience is best expressed by the recommendations on my resume. I will let those speak for me. I get emotional for a living. Experience Character/Cinematic Supervisor at Sucker Punch Productions September 2009 - Present (5 years 5 months) Responsible for working with Animation, Character, Design, Environment, and Engineering teams to develop characters, cinematics, animations, animation rigs and pipelines. Taking that information and applying it to schedules for the character, cinematic, and animation artists, and making sure everything is on track. Collaborating with the Art Director to make sure our style fits with the rest of the visuals. Then creating characters and animation that will help define that style and inspire the art team. Co-Founder/Character Director at Dreamhive, LLC October 2006 - August 2009 (2 years 11 months) Besides co-founding the studio, I was the Character Director and Director of Client Affairs. As Director of Client Affairs, I was responsible for landing and managing contracts with Morgan Rose, Ready at Dawn, EA Salt Lake, SCEA, BottleRocket, and Madonna. I was also the key person in setting up a very exciting partnership with Jason Rubin, Andy Gavin, and Jason Kay's entertainment group, Monkey Gods A Character Director for our studio, I performed various Character Modeling, Texturing, and Rigging tasks. I also grew into an Animation Direction role on teams ranging from 5 to 10 animators working remotely on several projects. I also pioneered new ground beta testing Autodesk's Mudbox software. My techniques for using the software caught the eye of Autodesk and they had me do multiple talks up and down the east coast. -

Game Narrative Review

Game Narrative Review ==================== Your name (one name, please): Jessica Lichter Your school: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Your email: [email protected] Month/Year you submitted this review: 04/2017 ==================== Game Title: The Last of Us Platform: PlayStation 3/4 Genre: Action-adventure, survival horror Release Date: June 14, 2013 (PlayStation 3) July 29, 2014 (PlayStation 4) Developer: Naughty Dog Publisher: Sony Computer Entertainment Game Writer/Creative Director/Narrative Designer: Neil Druckmann Overview The Last of Us (TLOU) is a third person shooter action-adventure/survival horror game that follows the journey of a man named Joel twenty years after an outbreak of a mutant Cordyceps fungus and the resulting death of his daughter. Post-apocalyptic America is in ruins. Some survive in the wild, in quarantine zones, occupy lost cities, and everyone fights to stay alive. People not only have to worry about the zombie-like creatures (called the infected) produced by the outbreak, but other humans who pose threats as well. Joel takes on the task of smuggling fourteen-year-old Ellie, who was bitten by the infected yet has not been taken by the cordyceps disease, across the ravaged United States to an organization’s lab to test for a possible cure. The game draws players into a story full of emotion, outstanding visuals, flexible gameplay, and insight into a world which could potentially be our own someday. TLOU provides a unique experience in the way that the characters themselves feel remarkably real. The dialogue exchanged between Ellie and Joel seems like the type of conversation one would have with one of their friends or family, and the excellent writing put into these exchanges build the characters beyond the cut scenes. -

The Possibilities of the Video Game Exhibition

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-2017 The Possibilities of the Video Game Exhibition Elizabeth Legere 2762328 CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/145 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Possibilities of the Video Game Exhibition by Elizabeth Legere Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2017 Thesis Sponsor: 4/30/2017 Joachim Pissarro Date Signature [Joachim Pissarro] 4/30/2017 Constance DeJong Date Signature of Second Reader [Constance DeJong] DEDICATION This paper is dedicated to Iris Barry, the founder of MoMA’s Film Library in 1929 and the Film Department at MoMA’s first curator. She led the Film Department at MoMA to incredible success despite initial skepticism from the greater public. Her pioneering in promoting Film as a legitimate art form to the greater art world has inspired many of the ideas presented in this paper, and has encouraged me to dream bigger with regards to the future of the relationship between video games and art museums. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my primary advisor, Joachim Pissarro, for being willing to take on an unconventional thesis topic, and for inspiring me to push the boundaries of what I imagined I could accomplish. -

“How Can a Narrative Designer Encourage Empathy in Players?”

“How can a narrative designer encourage empathy in players?” Many video games seek to create a meaningful relationship between the player and NPCs in their in-game worlds. This can be a romantic, platonic or familial. Narrative designers want to create the illusion of a real emotional bond with a fictional game character, even though many of the stories these relationships exist in are linear. In screen-writing, there are distinct methods to generate empathy and engagement from the audience for characters on screen. However, players have agency, it is by the nature of the medium that they are able to shape and have a meaningful effect on the in-game world they are inhabiting. Viewers of film and literature do not have this ability. Thus, a problem arises. What is applicable from the language of film to generate these relationships in a medium where there is uncertainty about how a player will act? How does a narrative designer approach this issue? “What is taken to be real elicits emotions. What does not impress one as true and unavoidable elicits no emo- tion or a weaker one.”1 How can this scenario be avoided in games? Whilst cinematography and acting bring weight and meaning to a story and its characters, in Commented [ST1]: Not sure if this was meant to be a full stop but a comma would make the sentence flow much game development; animation, level and mechanic design, as well as several other disciplines better must also align and flow to successfully generate player empathy. This is what shall be explored, through investigating case studies of how it has been approached with different degrees of success in several video game titles.