An Idea in Good Currency: Collaborative Leadership in the National Security Community Rodger Shanahan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Counterinsurgency in a Test Tube

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Counterinsurgency in a Test Tube Analyzing the Success of the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI) Russell W. Glenn Prepared for the United States Joint Forces Command Approved for public release; distribution unlimited NATIONAL DEFENSE RESEARCH INSTITUTE The research described in this report was prepared for the United States Joint Forces Command. -

RAA Liaison Letter Winter 2019 Edition-Web

The Royal Australian Artillery LIAISON LETTER Winter 2019 See Associations & Organisations Section inside for how to join or for more information. The Official Journal of the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery Incorporating the Australian Gunner Magazine First Published in 1948 CONTENTS Editor’s Comment 1 Letters to the Editor 3 Regimental 9 Around the Regiment 33 Professional Papers 55 RAA Capability & Personnel 71 Associations & Organisations 79 LIAISON NEXT EDITION DEADLINE Contributions for the RAA Liaison Letter 2019 – Summer Edition should be forwarded to the LETTER Editor by no later than Friday 27th September 2019. Winter Edition Liaison Letter on‐line The Liaison Letter is on the DRN and can be 2019 found on the Head of Regiment - Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery (RRAA) Share Point Page: Incorporating the http://drnet/Army/RRAA/PublicationsOrders/Pa Australian Gunner Magazine ges/Publications.aspx It is also available on the Royal Australian Artillery Historical Company (RAAHC) & Australian Artillery Association websites. Publication information Front Cover: Gunners Fund Advertisement – Seeking Your Support Front Cover Theme by: Major DT (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Compiled and Edited by: Major DT (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Published by: Lieutenant Colonel N (Nick) Wilson, Head of Regiment Desktop Publishing: Major DT (Terry) Brennan & Assisted by Michelle Ray (Honorary Desktop Publisher) Front Cover & Graphic Design: DT (Terry) Brennan Printed by: Defence Publishing Service – Victoria Distribution: For issues relating to content or distribution contact the Editor on email: [email protected] or [email protected] Contributors are urged to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in their articles. -

RAA Liaison Letter Spring 2013

The Royal Australian Artillery LIAISON LETTER Spring Edition 2013 Exercise Talisman Sabre 2013 The Official Journal of the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery Incorporating the Australian Gunner Magazine First Published in 1948 CONTENTS Editor’s Comment 1 Letters to the Editor 2 Regimental 7 Operations 19 Capability 21 RAA Professional Papers 23 Around the Regiment 33 Personnel & Training 43 LIAISON Associations & Organisations 47 LETTER Spring Edition NEXT EDITION CONTRIBUTION DEADLINE Contributions for the Liaison Letter 2014 – Autumn 2013 Edition should be forwarded to the Editor by no later than Friday 14th February 2014. LIAISON LETTER ON-LINE Incorporating the The Liaison Letter is on the Regimental DRN web-site – Australian Gunner Magazine http://intranet.defence.gov.au/armyweb/Sites/RRAA/. Content managers are requested to add this to their links. Publication Information Front Cover: Exercise Talisman Sabre 13 Front Cover Concept by: Major D.T. (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Compiled and Edited by: Major D.T. (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Published by: Lieutenant Colonel Dave Edwards, Deputy Head of Regiment Desktop Publishing: Michelle Ray, Combined Arms Doctrine and Development Section, Puckapunyal, Victoria 3662 Front Cover & Graphic Design: Felicity Smith, Combined Arms Doctrine and Development Section, Puckapunyal, Victoria 3662 Printed by: Defence Publishing Service – Victoria Distribution: For issues relating to content or distribution contact the Editor on email: [email protected] or [email protected] Contributors are urged to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in their articles. The Royal Australian Artillery, Deputy Head of Regiment and the RAA Liaison Letter editor accept no responsibility for errors of fact. -

Projection to East Timor

Chapter 11 Projection to East Timor In August 1942 in New Guinea during the Second World War and in 1966 in Vietnam an accumulation of risks resulted in a small number of Australian troops facing several thousand well-equipped, well-trained and more experienced enemy troops. Fortunately, climate, terrain and the resilience of junior leaders and small teams, as well as effective artillery support in 1966, offset the numerical and tactical superiority of their opponents. Australian troops prevailed against the odds. If either of these two tactical tipping points had gone the other way, there would have been severe strategic embarrassment for Australia. There could have been public pressure for a change in Government and investigations into the competence of the Australian armed forces. For 48 hours in September 1999, renegade members of the Indonesian military forces and their East Timorese auxiliaries provoked members of an Australian vanguard of the International ForceÐEast Timor (INTERFET) in the streets of the East Timor capital, Dili. Indonesians outnumbered Australians, who carried only limited quantities of ammunition.1 On the night of 21 September, a 600-strong East Timorese territorial battalion confronted a 40-strong Australian vehicle checkpoint on Dili's main road. Good luck, superior night-fighting technology, the presence of armoured vehicles and discipline under pressure resulted in another historic tactical tipping point going Australia's way. Had there been an exchange of fire that night, there would have been heavy casualties on both sides and several hours of confused fighting between Australian, Indonesian and East Timorese territorial troops. There was also potential for Indonesian and Australian naval vessels to have clashed as Australian ships rushed to deliver ammunition to Australian troops, as well as for Australian transport aircraft and helicopters to have been attacked at Dili airport. -

Biographical Details

Major General Paul Symon, AO In January 1998, the then Lieutenant Colonel Paul Symon was appointed as the Commanding Officer of the First Field Regiment, RAA. During his tenure, the Regiment was an integrated regular/reserve unit based in Enoggera Barracks, Brisbane as the direct support regiment to the Sixth Brigade of the First Australian Division. Born in Melbourne in 1960, he graduated from the Royal Military College, Duntroon, in 1982 as recipient of the Sword of Honour and its senior cadet. He was allotted to the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery and enjoyed many postings with the gunners, culminating in unit command in 1998-1999. His career in the most senior ranks have included postings as the 47th Deputy Chief of the Army from December 2008 to September 2011, and as Director of the Defence Intelligence Organisation from September 2011 until the present (June 2014). Major General Symon served on operations four times. His most important joint command was in late 2005 until mid 2006 when appointed Commander Middle East. This appointment gave him national command responsibility for all soldiers, sailors and airmen/women in Iraq and Afghanistan. He advised the United Nations Special Representative in East Timor in the four months prior to the deployment of INTERFET. This entailed close liaison with the Indonesian military, Falantil and militia leaders prior to, during, and after the vote for independence in 1999. For his leadership in East Timor and in command, he was named a Member of the Order of Australia in the 2000 Queen’s Birthday honours list. In 1997 he served with the United Nations in South Lebanon and the Golan Heights in a period of significant tension between Hezbollah and the Israeli Defence Force. -

Raaliaison Letter Spring 2006

The Royal Australian Artillery LIAISON LETTER Spring Edition 2006 The Official Journal of the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery Incorporating the Australian Gunner Magazine First Published in 1948 RAA LIAISON LETTER Spring Edition 2006 Publication Information Front Cover: 2nd/10th Field Regiment in Focus (see ‘2nd/10th Unit Report’) Front Cover Design by: Corporal Michael Davis, 1st Joint Public Affairs Unit Edited and Compiled by: Major D.T. (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Published by: Deputy Head of Regiment, School of Artillery, Bridges Barracks, Puckapunyal, Victoria 3662 Desktop Publishing by: Michelle Ray, Combat Arms Doctrine and Development Section, Bridges Barracks, Puckapunyal, Victoria 3662 Printed by: Defence Publishing Service - Victoria Distribution: For issues relating to content or distribution contact the Editor on email [email protected] Contributors are urged to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in their articles; the Royal Australian Artillery, Deputy Head of Regiment and the RAA Liaison Letter editor accept no responsibility for errors of fact. The views expressed in the Royal Australian Artillery Liaison Letter are the contributors and not necessarily those of the Royal Australian Artillery, Australian Army or Department of Defence. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise for any statement made in this publication. RAA Liaison Letter 2006 - Spring Edition Contents Distribution 4 Editors Comment 5 Letters to the Editor -

LIAISON LETTER Spring 2017

The Royal Australian Artillery LIAISON LETTER Spring 2017 The Official Journal of the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery Incorporating the Australian Gunner Magazine First Published in 1948 CONTENTS Editor’s Comment 1 Letters to the Editor 2 Regimental 3 Professional Papers 15 Around the Regiment 35 Rest 55 RAA Capability & Personnel 63 Associations & Organisations 73 LIAISON NEXT EDITION DEADLINE Contributions for the RAA Liaison Letter 2018 – Winter Edition should be forwarded to the LETTER Editor by no later than Friday 11th May 2018. Liaison Letter on‐line The Liaison Letter is on the DRN and can be Spring Edition found on the Head of Regiment ‐ Royal 2017 Regiment of Australian Artillery (RRAA) Share Point Page: http://drnet/Army/RRAA/PublicationsOrders/Pa Incorporating the ges/Publications.aspx Unit Content Managers Australian Gunner Magazine are requested to add this to their links. It is also on the Royal Australian Artillery Historical Company (RAAHC) & Australian Artillery Association websites. Publication information Front Cover: A Snap Shot of Regimental Life Front Cover Theme by: Major DT (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Compiled and Edited by: Major DT (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Published by: Brigadier Craig Furini AM, CSC, Head of Regiment Desktop Publishing: Major DT (Terry) Brennan & Assisted by Michelle Ray Front Cover & Graphic Design: DT (Terry) Brennan Printed by: Defence Publishing Service – Victoria Distribution: For issues relating to content or distribution contact the Editor on email: [email protected] or [email protected] Contributors are urged to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in their articles. -

Struggling for Self Reliance

STRUGGLING FOR SELF RELIANCE Four case studies of Australian Regional Force Projection in the late 1980s and the 1990s STRUGGLING FOR SELF RELIANCE Four case studies of Australian Regional Force Projection in the late 1980s and the 1990s BOB BREEN Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/sfsr_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Breen, Bob. Title: Struggling for self reliance : four case studies of Australian regional force projection in the late 1980s and the 1990s / Bob Breen. ISBN: 9781921536083 (pbk.) 9781921536090 (online) Series: Canberra papers on strategy and defence ; 171 Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Australia--Armed Forces. National security--Australia. Australia--Defenses--Case studies. Dewey Number: 355.033294 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. The Canberra Papers on Strategy and Defence series is a collection of publications arising principally from research undertaken at the SDSC. Canberra Papers have been peer reviewed since 2006. All Canberra Papers are available for sale: visit the SDSC website at <http://rspas. anu.edu.au/sdsc/canberra_papers.php> for abstracts and prices. Electronic copies (in pdf format) of most SDSC Working Papers published since 2002 may be downloaded for free from the SDSC website at <http://rspas.anu.edu.au/sdsc/working_papers.php>. The entire Working Papers series is also available on a ‘print on demand’ basis. -

RAA Liaison Letter Spring 2012

The Royal Australian Artillery LIAISON LETTER Spring Edition 2012 The Official Journal of the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery Incorporating the Australian Gunner Magazine First Published in 1948 CONTENTS Editor’s Comment 1 Letters to the Editor 3 Regimental 8 Operations 20 Capability 26 Professional Papers 28 RAA Take Post 48 Personnel & Training 54 Around the Regiments 60 LIAISON Associations & Organisations 78 LETTER NEXT EDITION CONTRIBUTION DEADLINE Contributions for the Liaison Letter 2013 – Autumn Edition should be forwarded to the editor by no later Spring Edition than Friday 23rd February 2013. 2012 LIAISON LETTER ON-LINE The Liaison Letter is on the Regimental DRN web-site at http://intranet.defence.gov.au/armyweb/Sites/RRAA/. Incorporating the Content managers are requested to add this to their links. Australian Gunner Magazine Publication Information Front Cover: Top L ef t: Lance Bombardier Dan Cooke from the Artillery Training Advisory Team Four at the Kabul Military Training Centre during a live fire exercise. Photograph by Sergeant Mick Davis. Top Right: Bombardier Jordan Haskins at the Counter Rocket Artillery and Mortar (CRAM) system at the Multi National Base Tarin Kot, Afghanistan. Photograph by Corporal Mark Doran. Bottom Left: Bombardier Michael Cross looks down a bustling street in downtown Dili, as his patrol waits to rendezvous with a New Zealand Army Patrol. Photograph by Corporal Chris Moore. Bottom Right: Bombardier Kane Robertson from the Artillery Training Advisory Team Four with instructor, Staff Sergeant Leyagat Khawah from the Afghan National Army at the Kabul Military Training Centre during a live fire exercise. Photograph by Sergeant Mick Davis. -

CREATING ONE DEFENCE First Principles Review CREATING ONE DEFENCE 2 First Principles Review | CREATING ONE DEFENCE CONTENTS

First Principles Review CREATING ONE DEFENCE First Principles Review CREATING ONE DEFENCE 2 First Principles Review | CREATING ONE DEFENCE CONTENTS Foreword 5 Key Recommendations 7 Specific Recommendations 9 Creating One Defence Chapter 1: One Defence – Case for Change 11 Chapter 2: One Defence – A Strong, Strategic Centre 19 Chapter 3: One Defence – Capability Development Life Cycle 31 Chapter 4: One Defence – Corporate and Military Enablers 43 Chapter 5: One Defence – Workforce 53 Optimising Resources and Implementation Chapter 6: One Defence – Optimising Resources and Dispelling Myths 63 Chapter 7: One Defence – Implementation 71 Annexes 79 A. Terms of Reference including alignment with recommendations 81 B. Framework for the First Principles Review of Defence 89 C. Recurring themes identified in recent reviews 91 D. Growth in Defence senior leadership numbers 95 E. Capability Development Life Cycle 97 F. Australian Public Service classifications and Australian Defence Force equivalent ranks 99 G. List of stakeholder interviews 101 H. Departmental Secretariat 107 First Principles Review | CREATING ONE DEFENCE 3 4 First Principles Review | CREATING ONE DEFENCE FOREWORD I am pleased to present the Report of the First Principles Review Team. In August 2014, the previous Minister for Defence appointed the team to undertake the First Principles Review of Defence. I was asked to chair the review team comprised of Professor Robert Hill, Professor Peter Leahy, Mr Jim McDowell and Mr Lindsay Tanner. The membership of the review team brought together a range of perspectives and a wealth of experience and expertise. We were ably supported by Roxanne Kelley, Major General Paul Symon and their secretariat1 as well as the Boston Consulting Group. -

Four Case Studies of Australian Regional Force Projection in the Late 1980S and the 1990S

STRUGGLING FOR SELF RELIANCE Four case studies of Australian Regional Force Projection in the late 1980s and the 1990s STRUGGLING FOR SELF RELIANCE Four case studies of Australian Regional Force Projection in the late 1980s and the 1990s BOB BREEN Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/sfsr_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Breen, Bob. Title: Struggling for self reliance : four case studies of Australian regional force projection in the late 1980s and the 1990s / Bob Breen. ISBN: 9781921536083 (pbk.) 9781921536090 (online) Series: Canberra papers on strategy and defence ; 171 Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Australia--Armed Forces. National security--Australia. Australia--Defenses--Case studies. Dewey Number: 355.033294 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. The Canberra Papers on Strategy and Defence series is a collection of publications arising principally from research undertaken at the SDSC. Canberra Papers have been peer reviewed since 2006. All Canberra Papers are available for sale: visit the SDSC website at <http://rspas. anu.edu.au/sdsc/canberra_papers.php> for abstracts and prices. Electronic copies (in pdf format) of most SDSC Working Papers published since 2002 may be downloaded for free from the SDSC website at <http://rspas.anu.edu.au/sdsc/working_papers.php>. The entire Working Papers series is also available on a ‘print on demand’ basis. -

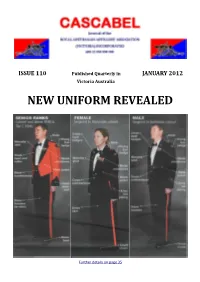

Issue110 – Jan 2012

ISSUE 110 Published Quarterly in JANUARY 2012 Victoria Australia NEW UNIFORM REVEALED Further details on page 35 Article Pages Assn Contacts, Conditions & Copyright 3 & 4 The President Writes/Membership Report 5 From The Colonel Commandant 6 CO 2/10 Fd Regt 7 Editors’ Indulgence 9 RAA Luncheon 10 Origins of the Tank – Part 3 11 A 7 minute photo shoot 15 What is the main ingredient of WD-40? 16 Major General P. L. Brereton, AM, RFD 17 Quote from Harold + Long Tan documentary trailer 18 The battle of Maryang San 19 Some other military reflections - TEWTs 20 Viet vets honoured with citation 23 Definition!!! of a “Drop Short” + Distinguished RAAF Squadrons 24 Best of British traditions 25 Minister for Defence - Paper on Afghanistan 26 They will make a telling difference 27 Darwin Military Museum + Maxine at her best 29 A Proud Gunner + Canadian vehicles on loan 30 Australian and US Marine artillery crews team up 31 Fired up in the kitchen 32 How slow can a SR-71 fly 33 Arty celebrates milestones 34 Facelift for mess dress 35 For exemplary service 36 WW11 - Little known history + Space exploration 37 Gunners take on Viper 38 VALE - Cpl Ashley Birt: Capt Bryce Duffy: LCpl Luke Gavin 39 Family statement for Craftsman Beau Pridue 40 VALE - Lt Gen Donald Dunstan 41 RAA Association (Vic) Inc Corp Shop 42 Parade Card/Changing your address? See cut-out proforma 43 Current Postal Addresses All mail for the Association, except matters concerning Cascabel, should be addressed to: The Secretary RAA Association (Vic) Inc. 8 Alfada Street Caulfield South Vic.