The Scottish-Canadian Coast Range Expedition, 1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1922 Elizabeth T

co.rYRIG HT, 192' The Moootainetro !scot1oror,d The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME FIFTEEN Number One D EC E M BER 15, 1 9 2 2 ffiount Adams, ffiount St. Helens and the (!oat Rocks I ncoq)Ora,tecl 1913 Organized 190!i EDITORlAL ST AitF 1922 Elizabeth T. Kirk,vood, Eclttor Margaret W. Hazard, Associate Editor· Fairman B. L�e, Publication Manager Arthur L. Loveless Effie L. Chapman Subsc1·iption Price. $2.00 per year. Annual ·(onl�') Se,·ent�·-Five Cents. Published by The Mountaineers lncorJ,orated Seattle, Washington Enlerecl as second-class matter December 15, 19t0. at the Post Office . at . eattle, "\Yash., under the .-\0t of March 3. 1879. .... I MOUNT ADAMS lllobcl Furrs AND REFLEC'rION POOL .. <§rtttings from Aristibes (. Jhoutribes Author of "ll3ith the <6obs on lltount ®l!!mµus" �. • � J� �·,,. ., .. e,..:,L....._d.L.. F_,,,.... cL.. ��-_, _..__ f.. pt",- 1-� r�._ '-';a_ ..ll.-�· t'� 1- tt.. �ti.. ..._.._....L- -.L.--e-- a';. ��c..L. 41- �. C4v(, � � �·,,-- �JL.,�f w/U. J/,--«---fi:( -A- -tr·�� �, : 'JJ! -, Y .,..._, e� .,...,____,� � � t-..__., ,..._ -u..,·,- .,..,_, ;-:.. � --r J /-e,-i L,J i-.,( '"'; 1..........,.- e..r- ,';z__ /-t.-.--,r� ;.,-.,.....__ � � ..-...,.,-<. ,.,.f--· :tL. ��- ''F.....- ,',L � .,.__ � 'f- f-� --"- ��7 � �. � �;')'... f ><- -a.c__ c/ � r v-f'.fl,'7'71.. I /!,,-e..-,K-// ,l...,"4/YL... t:l,._ c.J.� J..,_-...A 'f ',y-r/� �- lL.. ��•-/IC,/ ,V l j I '/ ;· , CONTENTS i Page Greetings .......................................................................tlristicles }!}, Phoiitricles ........ r The Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and the Goat Rocks Outing .......................................... B1/.ith Page Bennett 9 1 Selected References from Preceding Mount Adams and Mount St. -

Uvic Thesis Template

Dendroclimatological and dendroglaciological investigations at Confederation and Franklin glaciers, central Coast Mountains, British Columbia, Canada. by Bethany L. Coulthard B.A., Mount Allison University, 2007 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Department of Geography © Bethany Coulthard, 2009 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Dendroclimatological and dendroglaciological investigations at Confederation and Franklin glaciers, central Coast Mountains, British Columbia, Canada. by Bethany L. Coulthard B.A., Mount Alison University, 2007 Supervisory Committee Dr. Dan J. Smith, (Department of Geography) Supervisor Dr. J. Gardner, (Department of Geography) Departmental Member Dr. T. Lacourse, (Department of Geography) Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Dan J. Smith, (Department of Geography) Supervisor Dr. J. Gardner, (Department of Geography) Departmental Member Dr. T. Lacourse, (Department of Geography) Departmental Member It has become increasingly clear that climate fluctuations during the Holocene interval were unusually frequent and rapid, and that our current understanding of the temporal and spatial distribution of these oscillations is incomplete. Little paleoenvironmental research has been undertaken on the windward side of the central Coast Mountains of British Columbia, Canada. Very high annual orographic precipitation totals, moderate annual temperatures regulated by the Pacific Ocean, and extreme topographic features result in a complex suite of microclimate conditions in this largely unstudied area. Dendroclimatological investigations conducted on a steep south-facing slope near Confederation and Franklin glaciers suggest that both mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana) and subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) trees at the site are limited by previous year mean and maximum summer temperatures. -

Download Download

"BEING A GIRL WITHOUT BEING A GIRL": Gender and Mountaineering on Mount Waddingtotty 1926-36 KAREN ROUTLEDGE LIVE IN A CITY SHAPED BY MOUNTAINS. I first realize this while standing on top of one. It is 8:00 AM on the summit of Mount Baker, a Cascade Ivolcano just south of the American border. The summer morning is already scorching; snow glitters and melts at my feet. I am looking at the region where I have spent most of my life, but it has become another planet: alien, stunningly beautiful, yet somehow familiar. The view is dizzying; there's so much light, so much heat, so much air. All around me, peaks are stacked upon peaks, layers of paling blue fading into the sun-bleached sky. The sight of all this land at once is overwhelming. I know this place but not like this. Ironically, while Mount Baker's snow-capped plateau is a prominent landmark to Vancouverites, the city is utterly insignificant from here. Vancouver lies buried somewhere to the northwest, a squat grey mass in a valley of haze and smog, a sprawling city limited by mountains in three directions. I look down at this map made real before me and finally understand the extent to which geography shapes the way we live. The mountains that surround Vancouver are far more than landmarks, sources of income, and tourist beacons. We have changed these mountains and been changed by them. From their slopes and summits, countless city people have glimpsed not only their home from a different perspective but also their own lives, values, and priorities. -

SKI-CLIMBS in the COAST RANGE by W

34 CANADIAN SKI ANNUAL SKI-CLIMBS IN THE COAST RANGE By W. A. DON MUNDAY. Reprinted from The Canadian Alpine Journal, 1930 THREE seasons in the Mount Waddington cliff amused us. One cub always tarried just section of the Coast Range fully convinced too long, then hunted the rest of the family us that skis were logical equipment to over- while the family hunted him elsewhere. come the obstacles imposed by the immense Remarkable changes had taken place on snowfields. Faster travelling meant ex- the glacier since 1927. The wide white tending one's effective climbing range, there- corridor between the two medical moraines by making it possible to take advantage of was now a gorge from 100 to 200 feet in brief spells of favorable weather where un- depth. Areas of formerly clear ice were now settled weather naturally resulted from sea- littered with moraine. Some of the surface winds sweeping up abruptly . 10,000 feet streams flowed in canyons 50 feet below the across the glacial mantle of the range. general level. We landed at the mouth of the Franklin On the 14th we went through to base River, at the head of the Knight Inlet, on camp at 5,400 feet, arriving about 5 p.m., July 9, 1930, and started up the valley next after a climb of 5,000 feet in the course of morning with the ftrst packs. Erosion of the about 12 miles. The unceasing wind down river banks forced us to do much cutting of the glacier proves wearying. The worst part new trail through thick second-growth and of the trip \vas what we called the "swamp," brush, including some devil's club fIfteen opposite Confederation Glacier where sod feet high. -

In Memoriam COMPILED by GEOFFREY TEMPLEMAN

In Memoriam COMPILED BY GEOFFREY TEMPLEMAN The Alpine Club Obituary Year ofElection Sir Douglas Laird Busk 1927 (Hon 1976) Phyllis B Munday Hon LAC 1937 Paul Bauer 1933 & 1953 Stephen David Padfield 1976 Guy Dufour 1968 The Very Rev Harold Claude Noel Williams 1958 Robert Carmichael Stuart Low 1983 Dennis Kemp ACG 1953,1967 Esme M Speakman LAC 1946 Francis Hugh Keenlyside 1948 Countess Dorothea Gravina LAC 1955 Thomas Fitzherbert Latham (d 1987) 1955 Johannes Adolf Noordyk 1974 William J March 1987 William David Brown 1949 Maurice Bennett 1959 Richard Ayrton 1956 Irene Poole LAC 1931 Leslie Ashcroft Ellwood (d 1988) 19 2 3 The tribute to J Monroe Thorington, who died in 1989, was received anonymously from America; I am pleased to be able to print it here. J Monroe Thorington 1894-1989 Dr Thorington was born atPhiladelphia in 1894. His grandfather, who joined a fur company out of St Louis in 1837 and spent two years on the Western Plains, became US Senator for Iowa, and was American Consul on the Isthmus of Panama during the French administration. His father, James Thorington, served as surgeon of the Panama Railroad during this period before coming to Philadelphia. The subject of this memoir graduated from Princeton in 1915, received his MD from the University of Pennsylvania in 1919 and, after residency at the Presbyterian Hospital, began the practice of ophthalmology. During 1917 he worked at the American Ambulance Hospital, Neuilly-sur-Seine, and then for 294 THE ALPINE JOURNAL six years he was Instructor in Ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania and became Associate Ophthalmologist at the Presbyterian Hospital. -

Kathryn Bridge

MEDIA IMAGES Media Images for Curious, Royal BC Museum at Wing Sang, June 14 – Sept 3, 2012 Images available from: [email protected] or by calling 250-387-3207 (or 250-387-2101) The four concurrent exhibitions in the 7,500 sq ft space are: Artifact|Artifiction; Intimate Glimpses; Magic Lantern; Bottled Beauty. Wing Sang building at 51 East Pender, in Vancouver’s Chinatown, built in 1889. Photo: Martin Tessler Mockup of the Wing Sang building as it will look from June 14 to September 3, 2012 during the Royal BC Museum’s Curious exhibition. Intimate Glimpses Emily Carr – the evolution of an artist Credit: © Royal BC Museum, BC Archives. Emily Carr wearing cape and tam, 1901. Photographer (attributed to) John Douglas, St. Ives, England. I- 60891. Emily Carr, age 30, poses for the camera in 1901. Her cape dates to the 1890s, perhaps purchased while in England. Intimate Glimpses Emily Carr – the evolution of an artist Credit: © Royal BC Museum, BC Archives. The two friends are short, cannot see over the crowds and miss most of Queen Victoria’s funeral procession. Sketch and prose from Emily Carr “funny book” tracing her adventures with friend and fellow boarder Beatrice Hannah Kendall, London 1901. On loan, private collection. Note: This sketch and the prose below would have appeared on opposing pages in the handmade book Emily Carr gave to her friend Hannah Kendall. Intimate Glimpses Emily Carr – the evolution of an artist Credit: © Royal BC Museum, BC Archives. The two friends are short, cannot see over the crowds and miss most of Queen Victoria’s funeral procession. -

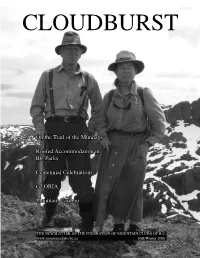

Cloudburst Fall 2006.Indd

CLOUDBURST On the Trail of the Mundays Roofed Accommodation in BC Parks Centennial Celebrations GLORIA Mountain Caribou THE NEWSLETTER OF THE FEDERATION OF MOUNTAIN CLUBS OF B.C. www.mountainclubs.bc.ca Fall/Winter 2006 CLOUDBURST Cloudburst is published semi-annually by the Federation Club Membership of Mountain Clubs of BC. Publication/Mail sales Please contact the FMC office to receive a list Agreement # 41309018. Printed by Hemlock Printers. of clubs that belong to the FMC (See inside back cover). Circulation 3,500. Membership is $15 per annum per membership when a member of a FMC Club and $25 per annum for individual members. Board of Directors President: Pat Harrison (VOA) Vice President: Peter Rothermel (IMR, ACC-VI) Articles: We welcome articles which inform our readers Secretary: vacant about mountain access, recreation, and conservation Treasurer: Don Morton (ACC-VI) issues or activities in B.C. Don’t limit yourself to prose: Directors: Paul Chatterton(Ind), Dave King (CR, ACC- photographs and poems also accepted. Pieces should not PG), Bill Perry (IMR), Ken Rodonets (CDMC), Manrico exceed 1,000 words. Scremin (ACC-Van), Eleanor Acker (NVOC) Committee Co-Chairs Submission Deadlines: Recreation and Conservation: vacant Fall/Winter - Oct 15 Trails: Pat Harrison, Alex Wallace Spring/Summer - April 15 Staff Executive Director: Evan Loveless Advertising: The FMC invites advertising or classified Bookkeeper: Kathy Flood advertising that would be useful to our members. For More Information Rates: www.mountainclubs.bc.ca $400 back page $300 full page PO Box 19673, Vancouver British Columbia $160 ½ page $80 ¼ page V5T 4E7 $40 business card Tel: 604-873-6096 Fax: 604-873-6086 Email: [email protected] Editor/Production: Meg Stanley (margaretmary@telus. -

BUTE INLET / MOUNT WADDINGTON STORIES by Rob Wood (Extracts from My Book “Towards the Unknown Mountains” – Ptarmigan Press

BUTE INLET / MOUNT WADDINGTON STORIES by Rob Wood (Extracts from my book “Towards the Unknown Mountains” – Ptarmigan Press 1991). 1. A short history of early explorations of Mt. Waddington. 2. Our first trip up Bute Inlet into the Waddington range. 3. A wintery ascent of Mt. Waddington from Bute. A SHORT HISTORY OF EARLY EXPLORATIONS OF MOUNT WADDINGTON British Columbia’s highest mountain, Mount Waddington, soars 13,177 feet above a barely penetrable shroud of remote and rugged wilderness with hundreds of square miles of cascading glaciers, thick- jungle and precipitous canyons, treacherous rivers and exposed ocean inlets with few natural harbours. The sheer size and inaccessibility of this formidable wilderness shroud might account for the fact that the mountain’s very existence was not fully recognized until 1925. It took a particularly adventurous and determined couple, Don and Phyllis Munday, to prove it. Though Captain Robert Bishop had sighted and triangulated the mountain in 1922, his report was lost amongst the files of the Canadian Geological Survey. Three years later the Mundays sighted a very big mountain, one hundred and fifty miles due north, from Mount Arrowsmith on Vancouver Island. It was, said Munday…., “the far-off finger of fate beckoning…a marker along the trail of adventure…a torch to set the imagination on fire.” Later that fall (1925) they headed up Bute Inlet and climbed Mount Rodney which rises almost eight thousand feet sheer out of the sea. From here they confirmed their discovery of what they called Mystery Mountain which would become the major preoccupation in their lives for the next ten years. -

Selected Excerpts from the Vancouver Natural History Society “Bulletin”

Selected Excerpts from the Vancouver Natural History Society “Bulletin” (With Notes and an Index) (Number 1, September, 1943 to Number 153, December 1971) Compiled by Bill Merilees Vancouver Natural History Society 2005 Dedication I would like to dedicate this contribution to our understanding of Greater Vancouver’s natural heritage to the members, past, present and future, of the Vancouver Natural History Society. To those past, for putting on record the observations and information contained within these pages, and to present and future members, in the hope that they will continue the ‘tradition’ as well as gain an appreciation of the Society’s roots and accomplishments. Along my personal path of life, three individuals have played very important roles in shaping my appreciation of the natural world. First is my father, Welborne Lawrence Merilees, whose love of the out doors, its vegetation and wildlife, first introduced me to Vancouver’s living heritage. Second is William Marsden Hughes, war veteran, bird- bander and V.N.H.S. Ornithology (Birding) Section leader during the late 1950’s and early 1960’s. Bill took me ‘under his wing’ and honed my skills in the techniques of field observation and data collection. Finally to Dr. Ian McTaggart-Cowan, Head of the Zoology Department and later Dean, Faculty of Graduate Studies at U.B.C., who further inspired and stimulated me to build on my curiosity from a more academic perspective. Along my path, an incredible number of individuals have ‘assisted the process’ in countless ways. Many, are mentioned within these pages. Introduction to the V.N.H.S. -

Bchn 1989 Summer.Pdf

MEMBER***** ********SOCIETIES Member Societies and their secretaries are responsible for seeing that the correct address for their society is up-to-date. Please send any change to both the Treasurer and the Editor at the addresses inside the back cover. The Annual Return as at October V31 St should include telephone numbers for contact. Members’ dues for the year 1988/89 were paid by the following Members Societies: Alberni District Historical Society, Box 284, Port Alberni, B.C. V9Y 7M7 Atlin Historical Society, P0. Box 111, Atlin, B.C. VOW lAO BCHF - Gulf Island Branch, do Marian Worrall, Mayne Island, VON 2J0 BCHF - Victoria Section, do Charlene Rees, 2 - 224 Superior Street, Victoria, B.C. V8V 1T3 Burnaby Historical Society, 4521 Watling Street, Burnaby, B.C. V5J 1V7 Chemainus Valley Historical Society, PC. Box 172, Chemainus, B.C. VOR 1 KO Cowichan Historical Society, P0. Box 1014, Duncan, B.C. V9L 3Y2 District 69 Historical Society, PC. Box 3014, Parksville, B.C. VOR 2S0 East Kootenay Historical Association, PC. Box 74, Cranbrook, B.C. Vi C 4H6 Fraser Nechako Historical Society 2854 Alexander Cresent, Prince George, B.C. V2N 1J7 Golden & District Historical Society, Box 992, Golden,.B.C. VOA 1 HO Ladysmith Historical Society, Box 11, Ladysmith, B.C. VOR 2E0 Lantzville Historical Society, Box 501, Lantzville, B.C. VOR 2HO Nanaimo Historical Society, P0. Box 933, Station ‘A’, Nanaimo, B.C. V9R 5N2 Nanooa Historical and Museum Society, R.R.i, Box 22, Marina Way, Nanoose Bay, B.C. VOR 2R0 North Shore Historical Society, 623 East 10th Street, North Vancouver, B.C. -

A Crossing of the Coast RANGE of BRITISH Columbia

A Grossing of the Coast Range of British Columbia. 75 by some ugly stone-swept gullies, the crossing of which was obviously too dangerous to attempt. We worked over to the right, but found -ourselves completely cut off by a lipe of vertical ice cliffs below from which great masses were breaking off at frequent intervals. This left the centre icefall as the only alternative. We were all very despondent and returned disconsolately to the loads for a meal at 2.30. A cup of tea and ' satu ' put new heart into the party and we set off to attack the icefall. It was a terribly complicated affair and we had a strenuous time trying line after line. By 5.30 we had worked our way down the upper bit and become more hopeful of success. At dawn the following morning, from the ice ledge on which we were camped, we saw a sunrise which for beauty far surpassed any I had seen before. In the right and left foreground were the icy walls, steep-sided and grim, enclosing the head of the Maiktoli valley ; in front, beyond the tiny foreground of snow and immensely far below was a lake of vivid colour at the bottom of which we could see the Sunder dhunga River flowing away from us into a placid sea of cloud which stretched without a break over the plains of India. The day was one of heavy toil and no small excitement, but night found us sitting on a rock ledge some 3000 ft. lower down gazing out upon a scene similar in general detail to that of the morning, but now lit by the delicate rays of a full moon. -

British Columbia Historical Quarterly

L1E3RA’ L ROADS THE BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY JANUARY, 1949 BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Published by the Archives of British Columbia in co-operation with the British Columbia Historical Association. EDITOR. WILL.nD E. IRELAND. Provincial Archives, Victoria. ASSOCIATE EDITOR. MAnGE W0LFENDEN. Provincial Archives, Victoria. ADVISORY BOARD. J. C. G00DFELL0w, Princeton. T. A. RIcKAIn, Victoria. W. N. SAGE, Vanoowoer. Editorial communications should be addressed to the Editor. Subscriptions should be sent to the Provincial Archives, Parliament Buildings, Victoria, B.C. Price, 50c. the copy, or $2 the year. Members of the British Columbia Historical Association in good standing receive the Quarterly without further charge. Neither the Provincial Archives nor the British Columbia Historical Association assumes any responsibility for statements made by contributors to the magazine. The Quarterly is indexed in Faxon’s Annual Magazine Subject-Index and the Canadian Index. BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY “Any country worthy of a. future should be interested in its past.” VOL. XIII VICTORIA, B.C., JANuARY, 1949. No. 1 CONTENTS. PAGE. Letters from James Edwwrcl Fitzgerald to W. E. Gladstone concerning Vancouver Island and the Hudson’s Bay Company, 1848—1850. By Paul Knaplund 1 Sir John H. Pelly, Bart., Governor, Hudson’s Bay Company, 1822—1852. By Reginald Saw 23 An Official speaks out: Letter of the Hon. Philip J. Hankin to the Duke of Buckingham, March 11, 1870. Edited, with an introduction, by Willard E. Ireland 33 NOms AND COMMENTS: British Columbia Historical Association 39 Kamloops Museum Association 42 Contributors to this Issue 42 THE NORTHWEST BOOKSHELF: Simpson’s 1828 Journey to the Columbia.