An Analysis of Cocoa Production in Ghana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entry Requirements for Nursing Programmes

2020/2021 INSTRUCTIONS FOR APPLICATIONS INTO HEALTH TRAINING INSTITUTIONS MINISTRY OF HEALTH The Ministry of Health wishes to inform the general public the online admissions portal for the 2020/2021 th th academic year will officially open from Monday 17 February, 2020 to Saturday 30 May, 2020. Applications are invited from qualified candidates for entry into any of the Public Health Training Institutions in Ghana. Applicants must: 1. Purchase application codes from any Agricultural Development Bank (ADB) or Ghana Commercial Bank (GCB) branch at a cost of One Hundred Ghana Cedis (GH¢100.00). (This includes the cost of verification of results, SMS alerts and all other correspondence). th NB: i. All purchased vouchers are valid up to 10 June, 2020 if not used. ii. No postage envelopes are required as all correspondence will be via SMS or E-mail. 2. Upon payment, applicants will receive a voucher giving them a unique PIN and Serial Number. 3. Have a dedicated phone number and a personal valid e-mail address for all correspondence. [Please NOTE: Do not use email address of relations] 4. You will need you residential and Ghana Post Digital Address 5. Use the PIN code and Serial to access the application form online at https://healthtraining.gov.gh 6. Note that the online registration form is accessible only by the PIN and self-created password. 7. Follow the instructions carefully and fill the relevant stages of the admission process once the online application is opened. 8. Use the PIN and Serial Number to track the status of the admission process. -

Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO) CONTACT Mr

Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO) CONTACT Mr. Albert Arhin, CODEO National Coordinator +233 (0) 24 474 6791 / (0) 20 822 1068 Secretariat: +233 (0)244 350 266/ 0277 744 777 Email:[email protected]: Website: www.codeoghana.org CODEO’s Pre-election Environment Observation Statement ( 15th July- 31st August, 2016) STATEMENT ON THE VOTER REGISTER Introduction The Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO) is pleased to release its findings on the pre-election environment for the period mid July to 31st August, 2016. This report is the first in the series of CODEO’s pre-election environment observations for the 2016 presidential and parliamentary elections, and captures bi-weekly reports filed by CODEO’s Long Term Observers (LTOs) deployed across the country. The findings in this report are based on bi-weekly field reports submitted in the month of July and August from 134 out of the 138 constituencies randomly selected from the 10 regions of Ghana. Guided by a checklist, CODEO’s LTOs observe the general political environment, including election-related preparatory activities by state and non-state actors, civic/voter education programs as well as political party campaign activities. The LTOs also observe the conduct of the security agencies, electoral irregularities and pre-election disputes adjudication. Summary of Findings: The National Commission on Civic Education (NCCE) and the Electoral Commission (EC) have stepped-up civic/voter education across the country using radio as the main medium for educating the public. There is low visibility of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) working in the areas of election violence monitoring, and peace promotion activities. -

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana Small and medium forest enterprises (SMFEs) serve as the main or additional source of income for more than three million Ghanaians and can be broadly categorised into wood forest products, non-wood forest products and forest services. Many of these SMFEs are informal, untaxed and largely invisible within state forest planning and management. Pressure on the forest resource within Ghana is growing, due to both domestic and international demand for forest products and services. The need to improve the sustainability and livelihood contribution of SMFEs has become a policy priority, both in the search for a legal timber export trade within the Voluntary Small and Medium Partnership Agreement (VPA) linked to the European Union Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (EU FLEGT) Action Plan, and in the quest to develop a national Forest Enterprises strategy for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD). This sourcebook aims to shed new light on the multiple SMFE sub-sectors that in Ghana operate within Ghana and the challenges they face. Chapter one presents some characteristics of SMFEs in Ghana. Chapter two presents information on what goes into establishing a small business and the obligations for small businesses and Ghana Government’s initiatives on small enterprises. Chapter three presents profiles of the key SMFE subsectors in Ghana including: akpeteshie (local gin), bamboo and rattan household goods, black pepper, bushmeat, chainsaw lumber, charcoal, chewsticks, cola, community-based ecotourism, essential oils, ginger, honey, medicinal products, mortar and pestles, mushrooms, shea butter, snails, tertiary wood processing and wood carving. -

2012 CLCCG Annual Report

the Child Labor Cocoa Coordinating Group 2012 Annual Report Prepared by the Offices of Senator Tom Harkin, Representative Eliot Engel, The United States Department of Labor, The Government of Cote d’Ivoire, The Ghana Ministry on Employment and Social Welfare, and the International Chocolate and Cocoa Industry March 12, 2013 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE CHILD LABOR COCOA COORDINATING GROUP MARCH 2013 Contents Statement on Progress Towards the Reduction in Child Labor in the Cocoa Sectors in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana under the Framework of Action to Support Implementation of the Harkin-Engel Protocol .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Status of Efforts Made by the Governments of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana ........................................ 4 Programs under the Framework and Status of Financial Commitments .......................................... 4 Going Forward .................................................................................................................................. 8 For More Information ....................................................................................................................... 8 Appendix 1: Declaration of Joint Action to Support Implementation of the Harkin-Engel Protocol 10 Appendix 2: Framework of Action to Support the Implementation of the Harkin-Engel Protocol.... 11 Appendix 3: By-laws for Governance of the Child Labor Cocoa Coordinating Group (CLCCG) .... 19 -

Collaborating with Local Authorities to Eliminate the Worst Forms of Child Labour in Ghana’S Cocoa

Collaborating with Local Authorities to Eliminate the Worst Forms of Child Labour in Ghana’s cocoa. The case of Yen Daakye (YDK) Project, Ghana Community driven initiatives for the elimination of the worst forms of child labour and forced adult labour in the cocoa industry through a child-centred development approach. A collaborative effort by the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI), Participatory Development Associates (PDA) Ltd and seven district-based implementing partners. Prepared by: Participatory Development Associates (PDA) February, 2012 Please note, the views and opinions expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI) About the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI) Established in 2002, the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI) emerged from the 2001 Harkin/Engel Protocol as a non-profit Foundation that would support the cocoa sector to address the problem of child and forced labour in the cocoa supply-chain. ICI was set up as a multi-stakeholder initiative (MSI), harnessing the energies and expertise of the chocolate and cocoa industry, of civil society, and of governments in cocoa-producing nations, to bring about positive change in agricultural labour practices and in the elimination of child labour. Supported by individual chocolate and cocoa companies, ICI is led by a Board composed equally of industry and civil society (NGO) representatives. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) is an advisor to the Board. ICI’s programme is nationally driven and community centred, ensuring an approach based on actual local conditions and creating a way for each country and community to guide its own future. -

ACCOUNTING to the PEOPLE #Changinglives #Transformingghana H

ACCOUNTING TO THE PEOPLE #ChangingLives #TransformingGhana H. E John Dramani Mahama President of the Republic of Ghana #ChangingLives #TransformingGhana 5 FOREWORD President John Dramani Mahama made a pact with the sovereign people of Ghana in 2012 to deliver on their mandate in a manner that will change lives and transform our dear nation, Ghana. He has been delivering on this sacred mandate with a sense of urgency. Many Ghanaians agree that sterling results have been achieved in his first term in office while strenuous efforts are being made to resolve long-standing national challenges. PUTTING PEOPLE FIRST This book, Accounting to the People, is a compilation of the numerous significant strides made in various sectors of our national life. Adopting a combination of pictures with crisp and incisive text, the book is a testimony of President Mahama’s vision to change lives and transform Ghana. EDUCATION The book is presented in two parts. The first part gives a broad overview of this Government’s performance in various sectors based on the four thematic areas of the 2012 NDC manifesto.The second part provides pictorial proof of work done at “Education remains the surest path to victory the district level. over ignorance, poverty and inequality. This is self evident in the bold initiatives we continue to The content of this book is not exhaustive. It catalogues a summary of President take to improve access, affordability, quality and Mahama’s achievements. The remarkable progress highlighted gives a clear relevance at all levels.” indication of the President’s committment to changing the lives of Ghanaians and President John Dramani Mahama transforming Ghana. -

Shade Trees, Disease and Cocoa Production in Western Ghana – a Case Study

Shade trees, disease and cocoa production in Western Ghana – a case study MSc Thesis Plant Production Systems Miguel Correia Castillo Leitão March 2020 1 Shade trees, disease and cocoa production in Western Ghana – a case study MSc Thesis Plant Production Systems Name Student: Miguel Correia Castillo Leitão Registration Number: 971227-162-100 Study: MSc Plant Biotechnology –Specialization Molecular Plant Breeding and Pathology Chair group: Plant Production Systems Code Number: PPS-80436 Date: March 2020 Supervisors: dr. Marieke Sassen dr. Danaë M.A. Rozendaal Examiner: dr.ir. Maja Slingerland Disclaimer: this thesis report is part of an education program and hence might contain (minor) inaccuracies and errors. Correct citation: Leitão, M.C.C., 2019, Shade, disease and cocoa production in Western Ghana – a case study, MSc Thesis Wageningen University, 57 p. Contact: [email protected], [email protected] for access to data, models and scripts used for the analyses. 2 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 6 Summary ................................................................................................................. 8 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................10 Cocoa in West Africa ................................................................................................ 10 Reasons leading to low productivity ....................................................................... -

Drought Vulnerability

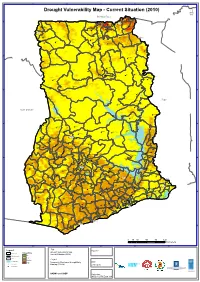

3°0'0"W 2°0'0"W 1°0'0"W 0°0'0" 1°0'0"E Drought Vulnerability Map - Current Situation (2010) ´ Burkina Faso Pusiga Bawku N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Gwollu Paga ° 1 1 1 1 Zebilla Bongo Navrongo Tumu Nangodi Nandom Garu Lambusie Bolgatanga Sandema ^_ Tongo Lawra Jirapa Gambaga Bunkpurugu Fumbisi Issa Nadawli Walewale Funsi Yagaba Chereponi ^_Wa N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 0 0 1 1 Karaga Gushiegu Wenchiau Saboba Savelugu Kumbungu Daboya Yendi Tolon Sagnerigu Tamale Sang ^_ Tatale Zabzugu Sawla Damongo Bole N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 9 9 Bimbila Buipe Wulensi Togo Salaga Kpasa Kpandai Côte d'Ivoire Nkwanta Yeji Banda Ahenkro Chindiri Dambai Kintampo N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 8 Sampa 8 Jema Nsawkaw Kete-krachi Kajeji Atebubu Wenchi Kwame Danso Busunya Drobo Techiman Nkoranza Kadjebi Berekum Akumadan Jasikan Odumase Ejura Sunyani Wamfie ^_ Dormaa Ahenkro Duayaw Nkwanta Hohoe Bechem Nkonya Ahenkro Mampong Ashanti Drobonso Donkorkrom Nkrankwanta N N " Tepa Nsuta " 0 Va Golokwati 0 ' Kpandu ' 0 0 ° Kenyase No. 1 ° 7 7 Hwediem Ofinso Tease Agona AkrofosoKumawu Anfoega Effiduase Adaborkrom Mankranso Kodie Goaso Mamponteng Agogo Ejisu Kukuom Kumasi Essam- Debiso Nkawie ^_ Abetifi Kpeve Foase Kokoben Konongo-odumase Nyinahin Ho Juaso Mpraeso ^_ Kuntenase Nkawkaw Kpetoe Manso Nkwanta Bibiani Bekwai Adaklu Waya Asiwa Begoro Asesewa Ave Dapka Jacobu New Abirem Juabeso Kwabeng Fomena Atimpoku Bodi Dzodze Sefwi Wiawso Obuasi Ofoase Diaso Kibi Dadieso Akatsi Kade Koforidua Somanya Denu Bator Dugame New Edubiase ^_ Adidome Akontombra Akwatia Suhum N N " " 0 Sogakope 0 -

SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES MANAGEMENT PROJECT (SFMP) Post Harvest Loss Reduction Study

SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES MANAGEMENT PROJECT (SFMP) Post Harvest Loss Reduction Study October 2015 This publication is available electronically on the Coastal Resources Center’s website at http://www.crc.uri.edu/projects_page/ghanasfmp/ For more information on the Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project, contact: USAID/Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project Coastal Resources Center Graduate School of Oceanography University of Rhode Island 220 South Ferry Rd. Narragansett, RI 02882 USA Tel: 401-874-6224 Fax: 401-874-6920 Email: [email protected] Citation: Dapaah, G., Samey, B. (2015). Post Harvesting Loss Reduction Study Report. The USAID/Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (SFMP). Narragansett, RI: Coastal Resources Center, Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island and SNV Netherlands Development Organization. GH2014_ACT016_SNV. 90 pp. Authority/Disclaimer: Prepared for USAID/Ghana under Cooperative Agreement (AID-641-A-15-00001) awarded on October 22, 2014 to the University of Rhode Island and entitled; the USAID/Ghana Sustainable Fisheries Management Project (SFMP). This document is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The views expressed and opinions contained in this report are those of the SFMP team and are not intended as statements of policy of either USAID or the cooperating organizations. As such, the contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the SFMP Project team and do not necessarily reflect -

Sector Strategic Medium Term Development Plan 2018-2021

REPUBLIC OF GHANA MINISTRY OF WORKS AND HOUSING (Draft) SECTOR STRATEGIC MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2018-2021 AUGUST 2017 For copies of the MWH SSMTDP, please contact the Public Relations Office of the Ministry: Ministry of Works and Housing PPBME Directorate Second Floor, Room 16 – 19 P o Box MB 43, Accra – Ghana The MWH SSMTDP (2018-2021) is also available on the internet at: www.mwh.gov.gh. i TABLE OF CONTENT For copies of the MWH SSMTDP, please contact the Public Relations Office of the Ministry:.........................................................................................................................................i TABLE OF CONTENT ...............................................................................................................ii LIST OF ACRONYMS................................................................................................................v LIST OF TABLES.....................................................................................................................viii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................................ix CHAPTER ONE ...........................................................................................................................1 PROFILE/CURRENT SITUATION/BASELINE ................................................................1 1.0 Introduction/Background ........................................................................................1 1.0.1 2018-2021 MTDP Structure. .....................................................................................1 -

Mapping Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities in Ghana

MAPPING FOREST LANDSCAPE RESTORATION OPPORTUNITIES IN GHANA 1 Assessment of Forest Landscape Restoration Assessing and Capitalizing on the Potential to Potential In Ghana To Contribute To REDD+ Enhance Forest Carbon Sinks through Forest Strategies For Climate Change Mitigation, Landscape Restoration while Benefitting Poverty Alleviation And Sustainable Forest Biodiversity Management FLR Opportunities/Potential in Ghana 2 PROCESS National Assessment of Off-Reserve Areas Framework Method Regional Workshops National National National - Moist Stakeholders’ Assessment of validation - Transition Workshop Forest Reserves Workshop - Savannah - Volta NREG, FIP, FCPF, etc 3 INCEPTION WORKSHOP . Participants informed about the project . Institutional commitments to collaborate with the project secured . The concept of forest landscape restoration communicated and understood . Forest condition scoring proposed for reserves within and outside the high forest zone 4 National Assessment of Forest Reserves 5 RESERVES AND NATIONAL PARKS IN GHANA Burkina Faso &V BAWKU ZEBILLA BONGO NAVRONGO TUMU &V &V &V &V SANDEMA &V BOLGATANGA &V LAWRA &V JIRAPA GAMBAGA &V &V N NADAWLI WALEWALE &V &V WA &V GUSHIEGU &V SABOBA &V SAVELUGU &V TOLON YENDI TAMALE &V &V &V ZABZUGU &V DAMONGO BOLE &V &V BIMBILA &V Republic of SALAGA Togo &V NKWANTA Republic &V of Cote D'ivoire KINTAMPO &V KETE-KRACHI ATEBUBU WENCHI KWAME DANSO &V &V &V &V DROBO TECHIMAN NKORANZA &V &V &V KADJEBI &V BEREKUM JASIKAN &V EJURA &V SUNYANI &V DORMAA AHENKRO &V &V HOHOE BECHEM &V &V DONKORKROM TEPA -

Assessment of Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities in Ghana

ASSESSMENT OF FOREST LANDSCAPE RESTORATION OPPORTUNITIES IN GHANA Final Report SEPTEMBER 2011 List of Acronyms CBO Community Based Organization CERSGIS Centre for Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Services CREMA Community Resource Management Areas DBH Diameter at Breast Height/Base Diameter EI Economic Index EU European Union FC Forestry Commission FLEGT Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade FORIG Forestry Research Institute of Ghana FSD Forest Services Division GHI Genetic Heat Index GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit HFZ High Forest Zone ITTO International Tropical Timber Organization IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature MTS Modified Taungya System NCRC Nature Conservation Research Centre NGO Non Governmental Organization N-REG Natural Resources and Environmental Governance PI Pioneer Index PROFOR Program on Forests REDD Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation RMSC Resource Management Support Center of the Forestry Commission SDSU South Dakota State University TZ Transition Zone UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization WD Wildlife Division of the Forestry Commission WRI World Resources Institute 2 Table of Contents List of Acronyms ............................................................................................................................. 2 Table of Contents ...........................................................................................................................