Drawing the Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Township Map - Rakhine State 92° E 93° E 94° E Tilin 95° E Township Myaing Yesagyo Pauk Township Township Bhutan Bangladesh Kyaukhtu !( Matupi Mindat Mindat Township India China Township Pakokku Paletwa Bangladesh Pakokku Taungtha Samee Ü Township Township !( Pauk Township Vietnam Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Nyaung-U !( Paletwa Saw Township Saw Township Ngathayouk !( Bagan Laos Maungdaw !( Buthidaung Seikphyu Township CHIN Township Township Nyaung-U Township Kanpetlet 21° N 21° Township MANDALAYThailand N 21° Kyauktaw Seikphyu Chauk Township Buthidaung Kyauktaw KyaukpadaungCambodia Maungdaw Chauk Township Kyaukpadaung Salin Township Mrauk-U Township Township Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Ponnagyun Township Township Minbya Rathedaung Sidoktaya Township Township Yenangyaung Yenangyaung Sidoktaya Township Minbya Pwintbyu Pwintbyu Ponnagyun Township Pauktaw MAGWAY Township Saku Sittwe !( Pauktaw Township Minbu Sittwe Magway Magway .! .! Township Ngape Myebon Myebon Township Minbu Township 20° N 20° Minhla N 20° Ngape Township Ann Township Ann Minhla RAKHINE Township Sinbaungwe Township Kyaukpyu Mindon Township Thayet Township Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Mindon Township !( Bay of Bengal Ramree Kamma Township Kamma Ramree Toungup Township Township 19° N 19° N 19° Munaung Toungup Munaung Township BAGO Padaung Township Thandwe Thandwe Township Kyangin Township Myanaung Township Kyeintali !( 18° N 18° N 18° Legend ^(!_ Capital Ingapu .! State Capital Township Main Town Map ID : MIMU1264v02 Gwa !( Other Town Completion Date : 2 November 2016.A1 Township Projection/Datum : Geographic/WGS84 Major Road Data Sources :MIMU Base Map : MIMU Lemyethna Secondary Road Gwa Township Boundaries : MIMU/WFP Railroad Place Name : Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) translated by MIMU AYEYARWADY Coast Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] Township Boundary www.themimu.info Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Yegyi Ngathaingchaung !( State/Region Boundary 2016. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020

United Nations A/75/288 General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020 Original: English Seventy-fifth session Item 72 (c) of the provisional agenda* Promotion and protection of human rights: human rights situations and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives Report on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar Note by the Secretary-General The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the General Assembly the report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar and on progress in the situation of human rights in Myanmar, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3. * A/75/150. 20-10469 (E) 240820 *2010469* A/75/288 Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Myanmar Summary The independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar issued two reports and four thematic papers. For the present report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights analysed 109 recommendations, grouped thematically on conflict and the protection of civilians; accountability; sexual and gender-based violence; fundamental freedoms; economic, social and cultural rights; institutional and legal reforms; and action by the United Nations system. 2/17 20-10469 A/75/288 I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3, in which the Council requested the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to follow up on the implementation by the Government of Myanmar of the recommendations made by the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar, including those on accountability, and to continue to track progress in relation to human rights, including those of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities, in the country. -

Download Report

Emergency Market Mapping and Analysis (EMMA) Understanding the Fish Market System in Kyauk Phyu Township Rakhine State. Annex to the Final report to DfID Post Giri livelihoods recovery, Kyaukphyu Township, Rakhine State February 14 th 2011 – November 13 th 2011 August 2011 1 Background: Rakhine has a total population of 2,947,859, with an average household size of 6 people, (5.2 national average). The total number of households is 502,481 and the total number of dwelling units is 468,000. 1 On 22 October 2010, Cyclone Giri made landfall on the western coast of Rakhine State, Myanmar. The category four cyclonic storm caused severe damage to houses, infrastructure, standing crops and fisheries. The majority of the 260,000 people affected were left with few means to secure an income. Even prior to the cyclone, Rakhine State (RS) had some of the worst poverty and social indicators in the country. Children's survival and well-being ranked amongst the worst of all State and Divisions in terms of malnutrition, with prevalence rates of chronic malnutrition of 39 per cent and Global Acute Malnutrition of 9 per cent, according to 2003 MICS. 2 The State remains one of the least developed parts of Myanmar, suffering from a number of chronic challenges including high population density, malnutrition, low income poverty and weak infrastructure. The national poverty index ranks Rakhine 13 out of 17 states, with an overall food poverty headcount of 12%. The overall poverty headcount is 38%, in comparison the national average of poverty headcount of 32% and food poverty headcount of 10%. -

(BRI) in Myanmar

MYANMAR POLICY BRIEFING | 22 | November 2019 Selling the Silk Road Spirit: China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Myanmar Key points • Rather than a ‘grand strategy’ the BRI is a broad and loosely governed framework of activities seeking to address a crisis in Chinese capitalism. Almost any activity, implemented by any actor in any place can be included under the BRI framework and branded as a ‘BRI project’. This allows Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and provincial governments to promote their own projects in pursuit of profit and economic growth. Where necessary, the central Chinese government plays a strong politically support- ive role. It also maintains a semblance of control and leadership over the initiative as a whole. But with such a broad framework, and a multitude of actors involved, the Chinese government has struggled to effectively govern BRI activities. • The BRI is the latest initiative in three decades of efforts to promote Chinese trade and investment in Myanmar. Following the suspension of the Myitsone hydropower dam project and Myanmar’s political and economic transition to a new system of quasi-civilian government in the early 2010s, Chinese companies faced greater competition in bidding for projects and the Chinese Government became frustrated. The rift between the Myanmar government and the international community following the Rohingya crisis in Rakhine State provided the Chinese government with an opportunity to rebuild closer ties with their counterparts in Myanmar. The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) was launched as the primary mechanism for BRI activities in Myanmar, as part of the Chinese government’s economic approach to addressing the conflicts in Myanmar. -

Rakhine Operational Brief WFP Myanmar

Rakhine Operational Brief WFP Myanmar OVERVIEW Rakhine State is located in the western part of Myanmar, bordering with Chin State in the north, Magway, Bago and Ayeyarwaddy Regions in the east, Bay of Bengal to the west and Chittagong Division of Bangladesh to the northwest. It is one of the most remote and second poorest state in Myanmar, geographically separated from the rest of the country by mountains. The estimated population of Rakhine State is 3.2 million. Chronic poverty and high vulnerability to shocks are widespread throughout the State. Acute malnutrition remains a concern in Rakhine. The food security situation is particularly critical in Buthidaung and Maungdaw townships with 15.1 percent and 19 percent prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM) among children 6-59 months respectively. Meanwhile the prevalence of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) is 2 percent and 3.9 percent - above WHO critical emergency thresholds. The prevalence of GAM in Sittwe rural and urban IDP camps is 8.6 percent and 8.5 percent whereas the SAM prevalence is 1.3 percent and 0.6 percent. The existing malnutrition has been exacerbated by the 2015 nationwide floods as a Multi-sector Initial Rapid Assessment (MIRA) reported that 22 percent of assessed villages in Rakhine having nutrition problems with feeding children under 2. Moreover, WFP and FAO’s joint Crops and Food Security Assessment Mission in December 2015 predicted the likelihood of severe food shortage particularly in hardest hit areas of Rakhine. WFP is the main humanitarian organization providing uninterrupted food assistance in Rakhine. Its first PARTNERSHIPS operation in Myanmar commenced in 1978 in northern Rakhine, following the return of 200,000 refugees from Government Counterpart Bangladesh. -

Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015

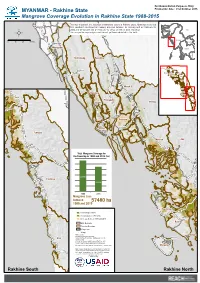

For Humanitarian Purposes Only MYANMAR - Rakhine State Production date : 21st October 2015 Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015 This map illustrates the evolution of mangrove extent in Rakhine State, Myanmar as derived Bhutan from Landsat-5 multispectral imagery acquired between 13 January and 23 February for Nepal Mindat 1988 and 30 January and 24 February for 2015 at 30m of pixel resolution. India China Town Bangladesh Bangladesh This is a preliminary analysis and has not yet been validated in the field. Paletwa Town Viet Nam Myanmar 0 10 20 30 Kms Laos Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Town Town Maungdaw Thailand Buthidaung Kyauktaw Cambodia Taungpyoletwea Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Town Buthidaung Kyauktaw Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Mrauk-U Town Maungdaw Rathedaung Mrauk-U Ponnagyun Town Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Pauktaw Minbya Sittwe Pauktaw Myebon Sittwe Myebon Ann Ann Mrauk-U Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu Ramree Ramree Toungup Rathedaung Mrauk-U Munaung Munaung Toungup Town Ann Thandwe Ponnagyun Thandwe Rathedaung Minbya Kyeintali Mindon Ma-Ei Town Town Town Gwa Gwa Ramree Minbya Town Ponnagyun Town Pauktaw Sittwe Pauktaw Town Sittwe Toungup Town Myebon Town Myebon Ann Toungup Town Total Mangrove Coverage for the Township in 1988 and 2015 (ha) Ann Town Thandwe Town 280986 Thandwe 223506 Kyaukpyu 1988 2015 Town Mangrove Loss between 57480 ha 1988 and 2015 Kyaukpyu New Mangrove area Kyeintali Town Remaining area 1988-2015 Ramree Decrease between 1988 and 2015 Town Ramree State Boundary Township Boundary Village-Tract Village Data sources: Toungup Landcover Analysis: UNOSAT Administrative Boundaries, Settlements: OCHA Munaung Gwa Town Roads: OSM Coordinate System: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N Contact: [email protected] File: REACH_MMR_Map_Rakhine_HVA_Mangrove_21OCT2015_A1 Munaung Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Gwa Town on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, associated, donors mentioned on this map. -

139416 Rakhine State

Rakhine State (Myanmar) as of 22 May 2013 Total Estimated IDP Population 139,416 Total Number of Households 22,773 Rakhine Situation Overview Inter-community conflict in Rakhine State, which erupted in early June 2012 and resurfaced in October 2012, has resulted in displacement and loss of lives and livelihoods. As of beginning of April 2013, the number of people displaced in Rakhine State has surpassed 139,000, of whom about 75,000 displaced since June 2012 and the remaining following Kyauktaw October. Many others continue living in tents close to their places of origin while their houses are being rebuilt, or with Maungdaw 6418 host families. The IDP population is currently hosted in 76 camps and camp-like settings. The Shelter/NFI/CCCM Cluster 3569 was activated in December 2012 in Yangon. Only more recently (middle March 2013) did the CCCM Cluster become Mrauk-U operational in Rakhine State. Therefore the sectoral response is still at a very early stage at field level. Rathedaung 4135 4008 Minbya Number of IDP sites by township IDP population by township 5152 as of 22 May 2013 as of 22 May 2013 Sittwe Pauktaw Minbya 8 Minbya 5,152 19976 Meybon Mrauk-U 4 Mrauk-U 4,135 89880 4169 Meybon 2 Meybon 4,169 Pauktaw 6 Pauktaw 19,976 Kyauktaw 11 Kyauktaw 6,418 Rathedaung 4 Rathedaung 4,008 Kyauk Phyu 2 Kyauk Phyu 1,849 Kyauk Phyu Ramree 2 Rakhine Ramree 260 1849 Sittwe 23 Sittwe 89,880 Maungdaw 14 Maungdaw 3,569 Type of accomodation at IDP sites Ramree Number of IDP sites IDP population by type of 260 'Planned / Managed Camp' purpose-built sites by type of accommodation accommodation where services and infrastructure is provided 139,416IDPs including water supply, food distribution, non- food item, education, and health care, usually targeted by humanitarian partners exclusively for the population of the site. -

Overall Impact of Climate-Induced Natural Disasters on the Public Health Sector in Myanmar (2008-2017)

RESEARCH PAPER Regional fellowship program Overall Impact of Climate-induced Natural Disasters on the Public Health Sector in Myanmar (2008-2017) Researcher : Ms. Khin Thaw Hnin, Fellow from Myanmar Direct Supervisor: Mr. Nou Keosothea, Senior Instructor Associate Supervisor: Ms. KemKeo Thyda, Associate Instructor February 2018 Editor: Mr. John Christopher, PRCD Director Notice of Disclaimer The Parliamentary Institute of Cambodia (PIC) is an independent parliamentary support institution for the Cambodian Parliament which, upon request of the parliamentarians and the parliamentary commissions, offers a wide range of research publications on current and emerging key issues, legislation and major public policy topics. This research paper provides information on subject that is likely to be relevant to parliamentary and constituency work but does not purport to represent or reflect the views of the Parliamentary Institute of Cambodia, the Parliament of Cambodia, or of any of its members, and Parliament of Myanmar, or of any of its members, the Parliament of Lao PDR, or of any of its members, the Parliament of Thailand, or of any of its members. The contents of this research paper, current at the date of publication, are for reference and information purposes only. These publications are not designed to provide legal or policy advice, and do not necessarily deal with every important topic or aspect of the issues it considers. The contents of this paper are covered by applicable Cambodian laws and international copyright agreements. Permission to reproduce in whole or in part or otherwise use the content on this website may be sought from the appropriate source. © 2018 Parliamentary Institute of Cambodia (PIC) Table of Contents 1. -

Rakhine State, Myanmar

World Food Programme S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 Photographs: ©FAO/F. Del Re/L. Castaldi and ©WFP/K. Swe. This report has been prepared by Monika Tothova and Luigi Castaldi (FAO) and Yvonne Forsen, Marco Principi and Sasha Guyetsky (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP secretariats with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Mario Zappacosta Siemon Hollema Senior Economist, EST-GIEWS Senior Programme Policy Officer Trade and Markets Division, FAO Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific, WFP E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS) has set up a mailing list to disseminate its reports. To subscribe, submit the Registration Form on the following link: http://newsletters.fao.org/k/Fao/trade_and_markets_english_giews_world S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. -

MYANMAR Civilians Displaced by fighting in Rakhine and Chin States As of 1 December 2019

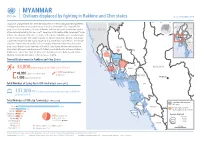

MYANMAR Civilians displaced by fighting in Rakhine and Chin states As of 1 December 2019 Thousands of people have been internally displaced since the escalation of fighting between INDIA the Myanmar Armed Forces and the Arakan Army (AA) in December 2018. Nearly 45,000 INDIA people have fled insecurity to 131 sites in Rakhine and Chin states with an unknown number BANGLADESH CHINA of people being hosted by families. As of 1 December 2019, Rakhine State Government figures indicate that about 43,000 people are displaced in 119 sites in Rakhine State and operational partners report around 1,800 displaced people are living in 12 sites in Chin State. Population Nay Pyi Taw movements remain fluid with regular reports of displacement and some returns. The number THAILAND of people displaced by this conflict increased sharply in November when more than 9,000 people were displaced in the townships of Mrauk-U, Rathedaung, Myebon and Buthidaung. PALETWA Intensified fighting and new displacements further complicate the humanitarian situation in BUTHIDAUNG CHIN Rakhine State where more than 131,000 people, including stateless Rohingya and Kaman MANDALAY Muslims, remain displaced since sectarian violence in 2012. MAUNGDAW Recent Displacement in Rakhine and Chin States KYAUKTAW PONNAGYUN MAGWAY people displaced by conflict as of 1 Dec’19 MINBYA 44,800 MRAUK-U RATHEDAUNG + 9,000 newly displaced 43,000 displaced in Rakhine State in November RAKHINE SITTWE Magway 1,800 displaced in Chin State PAUKTAW Sittwe MYEBON Total Number of Long-Term IDPs in Camps -

Overview of the Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipelines

Caring for Energy·Caring for You Overview of the Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipelines The Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipelines is an international cooperation project. The Myanmar-China Crude Oil Pipeline is jointly invested and constructed by SEAP and MOGE; their joint venture, South-East Asia Crude Oil Pipeline Company Limited (SEAOP), is responsible for its operation and management. While the Myanmar-China Gas Pipeline Project is jointly invested and constructed by SEAP, MOGE, POSCO DAEWOO, ONGC CASPIAN E&P B.V., GAIL and KOGAS; their joint venture, South-East Asia Gas Pipeline Company Limited (SEAGP), is responsible for its operation and management. Both joint ventures have adopted the General Meeting of Shareholders/Board of Directors for regulation and decision-making on major issues. Operational and management structure of JV companies of the Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipeline Project CNPC SEAP MOGE CNPC SEAP MOGE POSCO DAEWOO OCEBV GAIL KOGAS South-East Asia Crude Oil South-East Asia Gas Pipeline Pipeline Company Limited Company Limited Shareholders/ Shareholders/ Board of Directors Board of Directors 300,000-ton crude oil terminal on Madè Island 08 Myanmar-China Oil & Gas Pipeline Project (Myanmar Section) Special Report on Social Responsibility Myanmar-China Crude Oil Pipeline Myanmar-China Gas Pipeline The 771-kilometer long pipeline extends from Madè Island The Myanmar-China Gas Pipeline starts at Ramree Island on on the west coast of Myanmar to Ruili in the southwestern the western coast of Myanmar and ends at Ruili in China’s Chinese province of Yunnan, running through Rakhine Yunnan Province. Running in parallel with the Myanmar-China State, Magwe Region, Mandalay Region, and Shan State.