A Cross-Case Analysis on Models of Football Governance and the Influence of Supporter Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soccer, Culture and Society in Spain

Soccer, Culture and Society in Spain Spanish soccer is on top of the world, at both international and club levels, with the best teams and a seemingly endless supply of exciting and stylish players. While the Spanish economy struggles, its soccer flourishes, deeply embedded throughout Spanish social and cultural life. But the relationship between soccer, culture and society in Spain is complex. This fascinating, in-depth study shines new light on Spanish soccer by examining the role this sport plays in Basque identity, consol- idated in Athletic Club of Bilbao, the century-old soccer club located in the birthplace of Basque nationalism. Athletic Bilbao has a unique player-recruitment policy, allowing only Basque- born players or those developed at the youth academies of Basque clubs to play for the team, a policy that rejects the internationalism of contemporary globalized soccer. Despite this, the club has never been relegated from the top division of Spanish soccer. A particularly tight bond exists between the fans, their club and the players, with Athletic representing a beacon of Basque national identity. This book is an ethnography of a soccer culture where origins, ethnicity, nationalism, gender relations, power and passion, life-cycle events and death rituals gain new meanings as they become, below and beyond the playing field, a matter of creative contention and communal affirmation. Based on unique, in-depth ethnographic research, Soccer, Culture and Society in Spain investigates how a soccer club and soccer fandom affect the life of a community, interweaving empirical research material with key contemporary themes in the social sciences, and placing the study in the wider context of Spanish political and sporting cultures. -

Total Ballots Cast in 20051

TOTAL BALLOTS CAST IN 20051 Native Total Ballots American Black or Hawaiian or Cast by Indian or African Other Pacific Gender and Gender Ethnicity Alaska Native Asian American Islander Unknown White Ethnicity Female Hispanic or Latino 29 3 11 5 233 255 536 Not Hispanic or Latino 186 153 428 286 652 2149 3854 Unknown 103013435173 Female Total 216 156 442 291 1019 2439 4563 Male Hispanic or Latino 44 3 211 10 637 636 1541 Not Hispanic or Latino 1224 172 1979 228 783 90925 95311 Unknown 57 0 10 1 65 246 379 Male Total 1325 175 2200 239 1485 91807 97231 Organization Hispanic or Latino 3 1 12 0 559 307 882 Not Hispanic or Latino 474 184 1774 98 1296 168417 172243 Unknown 000000 0 Organization Total 477 185 1786 98 1855 168724 173125 Unknown Hispanic or Latino 000049554 Not Hispanic or Latino 5 4 18 13 936 534 1510 Unknown Total 5 4 18 13 985 539 1564 Total Ballots Cast by Race 2023 520 4446 641 5344 263509 276483 Ballot Summary LAA Total Eligible Voters 1,985,625 LAA Total Ballots Cast 276,483 Percentage of Eligible Voters that Cast Ballots 13.92% National Total of Ballots Disqualified 8,232 Percentage of Ballots Disqualified vs. Ballots Received 2.89% 1Represents only those local administrative areas (LAAs)required to conduct an election in 2005 1 TOTAL ELIGIBLE VOTERS IN 20051 Native American Black or Hawaiian or Total Voters Indian or African Other Pacific by Gender Gender Ethnicity Alaska Native Asian American Islander Unknown White and Ethnicity Female Hispanic or Latino 221 7 60 127 1343 2442 4200 Not Hispanic or Latino 1383 1455 4049 -

Ángel María Villar

3 ≠OPINIÓN autonómico es, en casi todos los ÁNGEL MARÍA VILLAR: casos, un hombre entregado a la causa del fútbol, generoso, solidario y sacrificado, ajeno a “UN FÚTBOL Y UNOS los flashes fáciles y volcado en una tarea que puede parecer DIRIGENTES CON oscura, pero que es todo lo contrario. Un dirigente de Terri - torial es el primer gestor de los GRANDES VALORES” éxitos que llegan. Hay muchos de ellos en el fútbol vizcaíno y estoy seguro de que continuará habiéndolo. Ese amor por este deporte va en nuestros genes. l fútbol vizcaíno es un La Federación Vizcaína cum - fútbol de grandes y ple este año, ahí es nada, cien Edemostrados valores. años de vida. Ha tenido que Los conocemos todos. Lo sabe - superar no pocas dificultades, mos todos. Esos valores han pero lo ha conseguido y no hay sido apreciados a nivel territo- mejor prueba de su capacidad rial y nacional. Los aficionados que haber llegado a Centenaria, a este maravilloso deporte que tras fundarse (21 de agosto de tanto une se han entusiasmado 1913) como Federación Norte, con nuestro juego, con la noble - con clubes de Bizkaia, Gipuz - za y deportividad de nuestros koa y Logroño. Desde entonces futbolistas, con una historia que recorrió un largo camino en el se convirtió en leyenda a lo que, por supuesto, no todo fue largo de 100 años. Muchos clu - cómodo. Los avatares sufridos bes le dieron forma y contribu- a lo largo de estos años y su - yeron a escribir sus incontables SALUDA DEL PRESIDENTE perados son la demostración páginas de oro y hubo, natural - DE LA REAL FEDERACIÓN palpable de lo capaz que ha mente, infinidad de dirigentes ESPAÑOLA DE FÚTBOL sido nuestro fútbol y de la talla anónimos, sacrificados, valien- de los dirigentes que han tes y generosos que se esforza - presidido la Territorial: 18. -

Intermediary Transactions 2019-20 1.9MB

24/06/2020 01/03/2019AFC Bournemouth David Robert Brooks AFC Bournemouth Updated registration Unique Sports Management IMSC000239 Player, Registering Club No 04/04/2019AFC Bournemouth Matthew David Butcher AFC Bournemouth Updated registration Midas Sports Management Ltd IMSC000039 Player, Registering Club No 20/05/2019 AFC Bournemouth Lloyd Casius Kelly Bristol City FC Permanent transfer Stellar Football Limited IMSC000059 Player, Registering Club No 01/08/2019 AFC Bournemouth Arnaut Danjuma Groeneveld Club Brugge NV Permanent transfer Jeroen Hoogewerf IMS000672 Player, Registering Club No 29/07/2019AFC Bournemouth Philip Anyanwu Billing Huddersfield Town FC Permanent transfer Neil Fewings IMS000214 Player, Registering Club No 29/07/2019AFC Bournemouth Philip Anyanwu Billing Huddersfield Town FC Permanent transfer Base Soccer Agency Ltd. IMSC000058 Former Club No 07/08/2019 AFC Bournemouth Harry Wilson Liverpool FC Premier league loan Base Soccer Agency Ltd. IMSC000058 Player, Registering Club No 07/08/2019 AFC Bournemouth Harry Wilson Liverpool FC Premier league loan Nicola Wilson IMS004337 Player Yes 07/08/2019 AFC Bournemouth Harry Wilson Liverpool FC Premier league loan David Threlfall IMS000884 Former Club No 08/07/2019 AFC Bournemouth Jack William Stacey Luton Town Permanent transfer Unique Sports Management IMSC000239 Player, Registering Club No 24/05/2019AFC Bournemouth Mikael Bongili Ndjoli AFC Bournemouth Updated registration Tamas Byrne IMS000208 Player, Registering Club No 26/04/2019AFC Bournemouth Steve Anthony Cook AFC Bournemouth -

10Th Annual Report 2013 National Joint Registry for England, Wales and Northern Ireland

HIPS KNEES ANKLES ELBOWS SHOULDERS PROMs 10th Annual Report 2013 National Joint Registry for England, Wales and Northern Ireland ISSN 1745-1450 (Online) Surgical data to 31 December 2012 Prepared by The NJR Editorial Board NJRSC Members Mr Martyn Porter (Chairman) Mick Borroff Professor Paul Gregg Professor Alex MacGregor Mr Keith Tucker NJR RCC Network Representatives Mr Peter Howard (Chairman) Mr Colin Esler Mr Alun John Mr Matthew Porteous Orthopaedic Specialists Professor Andy Carr Mr Andy Goldberg NJR Research Fellows Mr Jeya Palan Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership NJR Management Team and NJR Communications Rebecca Beaumont James Thornton Melissa Wright Elaine Young Northgate Information Solutions (UK) Ltd NJR Centre, IT and data management Olivia Forsyth Anita Mistry Dr Claire Newell Dr Martin Pickford Martin Royall Mike Swanson University of Bristol NJR Statistical support, analysis and research team Professor Yoav Ben Shlomo Professor Ashley Blom Dr Emma Clark Professor Paul Dieppe Dr Linda Hunt Dr Michèle Smith Professor Jonathan Tobias Kelly Vernon Pad Creative Ltd (design and production) This document is available in PDF format for download from the NJR website at www.njrcentre.org.uk This document is available in PDF format for download from the NJR website at www.njrcentre.org.uk National Joint Registry for England, Wales and Northern Ireland | 10th Annual Report Contents Chairman’s introduction 10 Foreword from the Chairman of the Editorial Board 12 Executive summary 13 Part 1: Annual progress ..............................................................................14 -

Basque Soccer Madness a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

University of Nevada, Reno Sport, Nation, Gender: Basque Soccer Madness A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Basque Studies (Anthropology) by Mariann Vaczi Dr. Joseba Zulaika/Dissertation Advisor May, 2013 Copyright by Mariann Vaczi All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Mariann Vaczi entitled Sport, Nation, Gender: Basque Soccer Madness be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Joseba Zulaika, Advisor Sandra Ott, Committee Member Pello Salaburu, Committee Member Robert Winzeler, Committee Member Eleanor Nevins, Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2013 i Abstract A centenarian Basque soccer club, Athletic Club (Bilbao) is the ethnographic locus of this dissertation. From a center of the Industrial Revolution, a major European port of capitalism and the birthplace of Basque nationalism and political violence, Bilbao turned into a post-Fordist paradigm of globalization and gentrification. Beyond traditional axes of identification that create social divisions, what unites Basques in Bizkaia province is a soccer team with a philosophy unique in the world of professional sports: Athletic only recruits local Basque players. Playing local becomes an important source of subjectivization and collective identity in one of the best soccer leagues (Spanish) of the most globalized game of the world. This dissertation takes soccer for a cultural performance that reveals relevant anthropological and sociological information about Bilbao, the province of Bizkaia, and the Basques. Early in the twentieth century, soccer was established as the hegemonic sports culture in Spain and in the Basque Country; it has become a multi- billion business, and it serves as a powerful political apparatus and symbolic capital. -

Total Eligible Ballots Cast by Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in 20111

Total Eligible Ballots Cast by Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in 20111 Native Hawaiian or Total Ballots Cast American Indian or Black or African Other Pacific by Gender, and Gender Ethnicity Alaska Native Asian American Islander Unknown White Ethnicity Female Hispanic or Latino 112 1 11 1 78 976 1179 Not Hispanic or Latino 164 125 411 106 3641 4447 Unknown 59 87 404 121 1053 1883 3607 Female Total 335 213 826 228 1131 6500 9233 Male Hispanic or Latino 35 10 21 14 249 1022 1351 Not Hispanic or Latino 654 187 824 134 43780 45579 Unknown 367 71 708 92 632 29504 31374 Male Total 1056 268 1553 240 881 74306 78304 Organization Hispanic or Latino 3 1 5 1 256 479 745 Not Hispanic or Latino 283 89 431 42 415 77086 78346 Unknown 120 42 385 28 1355 46887 48817 Organization Total 406 132 821 71 2026 124452 127908 Unknown Hispanic or Latino 2 1 2 20 74 99 Not Hispanic or Latino 5 8 53 21 438 1074 1599 Unknown 3 2 15 15 2102 465 2602 Unknown Total 10 11 70 36 2560 1613 4300 Total Ballots Cast by Race2 1807 624 3270 575 6598 206871 219745 Ballot Summary LAA Total Eligible Voters 1,894,630 LAA Total Ballots Cast 219,466 Percentage of Eligible Voters that Cast Ballots 12% National Total of Ballots Disqualified 14,631 Percentage of Ballots Disqualified vs. Ballots Received 7% 1Represents only those LAA's in which an election was held in 2011 2Due to Producers' ability to select more than 1 race, the Total Ballots Cast may be more than LAA Total Ballots Cast in the Ballot Summary Table Total Eligible Voters by Race, Ethinicity, and Gender in 20111 Native Hawaiian -

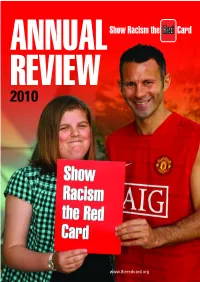

SRTRC-ANN-REV-2010.Pdf

ANNUAL REVIEW 2010 www.theredcard.org SHOW RACISM THE RED CARD MAJOR SPONSORS: SHOW RACISM THE RED CARD DVD and education pack £25 (inc p&p) The DVD is a fast moving and engaging 22 minutes exploration of racism, its origins, causes and practical ways to combat it. The film includes personal experiences of both young people and top footballers, such as Ryan Giggs, Thierry Henry, Rio Ferdinand and Didier Drogba. The education pack is filled with activities and discussion points complete with learning outcomes, age group suitability and curriculum links. SPECIAL OFFER: Buy ‘SHOW RACISM THE RED CARD’ with ‘ISLAMOPHOBIA/ A SAFE PLACE’ for a special price of £45 including p&p. For more information or to place an order email www.theredcard.org ANNUAL REVIEW 2010 FOREWORD CONTENTS Shaka Hislop, Honorary President Foreword by Shaka Hislop 1 What a year it has been for Show Racism the Red Card. Football crowds and club revenues continue to rise steadily Introduction by Ged Grebby 3 despite much of the world still gripped by the recession. Many people believe, and will say out loud, that football has Sponsorship 4 its own world. As the growing crowds also show an increase in the number of minority groups regularly attending games every weekend, a few ask ‘why the need Website 5 for an organisation such as Show Racism The Red Card?’ The stats speak for themselves. This has been a record year Leroy Rosenior 6 in terms of revenues raised and staff growth at well over 15%. The website also continues to show amazing growth Hall of Fame 7 and popularity and even on Facebook the fan numbers are very pleasing indeed. -

Back in Black ... and White!

Clap Your Hands, Stamp Your Feet £2.50 An independent view of Watford FC and football in general BACK IN BLACK ... AND WHITE! DOWNLOAD EDITION Please visit our Just Giving page and make a donation to The Bobby Moore Fund http://www.justgiving.com/CYHSYF Thank You! Geri says: “Good Lord! Are you Clap boys still going in glorious black and white? I may even pick up the mic and start miming again…” Credits The editorial team would like to extend their immense gratitude in no particular order to the following people, without whom this fanzine would not have been possible: Marvin Monroe Jay’s Mum Steve Cuthbert Tom Willis Woody Wyndham Josh Freedman Capt’n Toddy Martin & Frances Pipe Jamie Parkins (for the photos) Mike Parkin Hamish Currie Guy Judge Chris Lawton Martin Pollard Ed Messenger (since 1951) Tim Turner Bill Wilkinson our sellers Sam Martin and Ian Grant .. and of course to you our readers for buying it! Thanks a million! Barry and John While this edition is officially a ‘one off’ at the moment, if you would like to see Clap Your Hands Stamp Your Feet back on the streets at another date in future then please continue to send your padding to our email address over the next few months and if we get enough contributions we may yet be back in the springtime... yep, fairweather fanzine sellers - that’s us! [email protected] The views expressed in this fanzine are not necessarily shared by the editors and we take no responsibility for any offence or controversy arising from their publication. -

GUTIÉRREZ CHICO, Fernando.Pdf

Tesis Doctoral “Vencer menos para ganar más”. Singularidad deportiva, vínculo territorial y transversalidad de la identidad a través de hinchas del Athletic Bilbao. Fernando Gutiérrez Chico Doctorado en Ciencias Sociales Dirección: Dr. Íñigo González de la Fuente Dr. Ángel B. Espina Barrio 2020 Universidad de Salamanca (España) Facultad de Ciencias Sociales / Instituto de Iberoamérica A mis padres y a mi hermano por estar siempre, siempre, siempre ahí. Al Maestro, al gran José Iragorri porque siempre te tengo y te tendré muy presente. II Agradecimientos En primer lugar, a toda mi familia. Han sido cuatro intensos años de mucho trabajo. Han sido muchas horas sin dormir, muchas horas sin descansar. Mudanza para aquí, mudanza para allá; un empleo aquí, un empleo allá… y en todas y cada una de esas fases siempre he tenido vuestro aliento. Egoístamente, he de reconocer que en esos precisos momentos no era capaz de apreciar su valor en la justa medida. Sin embargo, al escribir estas líneas me doy cuenta de lo muy importante que ha resultado para que esta tesis haya podido salir adelante. Mamá, Papá, Raúl: ¡sois los mejores! No puedo olvidarme tampoco de todas y cada una de las personas que me han permitido acercarme a su universo athletictzale y han compartido conmigo sus experiencias y reflexiones rojiblancas. Todos y todas esas hinchas que habéis participado en esta investigación y de los que tanto he aprendido. Sin vosotros esta tesis no hubiera sido posible, así que sobre vosotros recae el mérito de este trabajo. Eskerrik asko! ¡Ay Doctor González de la Fuente! ¡Ay, Iñigo! ¿Por dónde empiezo contigo? Tendremos que hablar con Euskaltzaindia para que acuñen un nuevo término porque eskerrik asko se queda corto para todo lo que te tengo que agradecer. -

A Sale of Football & Sporting Memorabilia

SSppoorrttiinngg MMeemmoorryyss WWoorrllddwwiiddee AAuuccttiioonnss LLttdd PPrreesseenntt…….. AA SSaallee ooff FFoooottbbaallll && SSppoorrttiinngg MMeemmoorraabbiilliiaa LLIIVVEE AAUUCCTTIIOONN NNUUMMBBEERR 2299 At Holy Souls Social Club, opposite Midland School Wear, Acocks Green, Birmingham, B27 6BP Wednesday 7th August, 2019 – 12.15pm Photographs of all lots are available online at the-saleroom.com 11 Rectory Gardens, Castle Bromwich, Birmingham, B36 9DG Telephone: 0121 684 8282 Fax: 0121 285 2825 E-mail: [email protected] Visit: www.sportingmemorys.com 1 Terms & Conditions Date Of Sale The sale will commence at 12.15pm on Wednesday 7th August 2019. Venue The venue is the Holy Souls Social Club, opposite Midland School Wear, Acocks Green, Birmingham, B27 7BP Location The club is located on the Warwick Road, between Birmingham (5miles) and Solihull (3miles). The entrance to the club is via a drive way, located between the Holy Souls Church and Ibrahims Restaurant, opposite Midland School Wear shop. Clients requiring local accomodation are recommended to use the Best Western Westley Hotel, which is just 0.4miles from the venue. Plenty of other hotels are also located in Solihull/Birmingham area, to suit all varying budgets. Viewing Arrangements Viewing will take place as detailed on the opposite page. As the more valuable items are being stored at the local bank, viewing at any other time will be by arrangement with Sporting Memorys Worldwide Auctions Ltd Registration It is requested that all clients register before entering the viewing room. Auctioneers The Auctioneers conducting the sale are Trevor Vennett-Smith and Tim Davidson. Please note they are only acting for Sporting Memorys Worldwide Auctions on the sale day. -

Sport Gulf Times

GGOLFOLF | Page 4 CCRICKETRICKET | Page 3 India’s Taylor pays Sharma wins tribute to Joburg Open Crowe aft er in style 17th century Tuesday, December 12, 2017 FOOTBALL Rabia I 24, 1439 AH Real Madrid tie GULF TIMES a ‘wonderful opportunity’ for PSG SPORT Page 7 SPOTLIGHT FOOTBALL/QSL CUP Misbah to thrill Big wins for Kharaitiyat, in Qatar National Al Gharafa, and Duhail By Sports Reporter dulaziz al-Ansari compounded The Day cricket series Kings’ misery with goals in the 87th Doha The matches will be held at the 13,000-capacity Asian Town Stadium and 89th. ne-sided matches were the AL SAILIYA 0 AL GHARAFA 4 order of the day in the fi fth Abdulmajid Anad opened the scoring and fi nal round of the QSL in the eighth minute following a fumble OCup with Al Kharaitiyat, Al from the goalkeeper that allowed him Gharafa and Al Duhail recording huge to strike home into an empty net from victories in their Group A fi xtures. 25 yards at the Al Shamal Stadium. Al Kharaitiyat beat Qatar SC 6-1, Al Amro Seraj doubled the advantage Gharafa won 4-0 against Al Sailiya and for Al Gharafa just before half-time Al Duhail fi nished off their campaign with a weaving run before striking from with an 8-0 rout of Al Khor. distance and he secured the points in The results saw Al Gharafa, who had the 81st with a fi nish from close range. already qualifi ed for the semi-fi nals, Nasser al-Kaabi was on hand to confi rm fi rst position in the group with complete the scoring in the 86th.