Circa Single Pages.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trends in Southeast Asia

ISSN 0219-3213 2017 no. 9 Trends in Southeast Asia PARTI AMANAH NEGARA IN JOHOR: BIRTH, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS WAN SAIFUL WAN JAN TRS9/17s ISBN 978-981-4786-44-7 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 789814 786447 Trends in Southeast Asia 17-J02482 01 Trends_2017-09.indd 1 15/8/17 8:38 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre (NSC) and the Singapore APEC Study Centre. ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 17-J02482 01 Trends_2017-09.indd 2 15/8/17 8:38 AM 2017 no. 9 Trends in Southeast Asia PARTI AMANAH NEGARA IN JOHOR: BIRTH, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS WAN SAIFUL WAN JAN 17-J02482 01 Trends_2017-09.indd 3 15/8/17 8:38 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2017 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

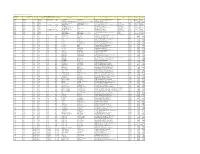

Buku Daftar Senarai Nama Jurunikah Kawasan-Kawasan Jurunikah Daerah Johor Bahru Untuk Tempoh 3 Tahun (1 Januari 2016 – 31 Disember 2018)

BUKU DAFTAR SENARAI NAMA JURUNIKAH KAWASAN-KAWASAN JURUNIKAH DAERAH JOHOR BAHRU UNTUK TEMPOH 3 TAHUN (1 JANUARI 2016 – 31 DISEMBER 2018) NAMA JURUNIKAH BI NO KAD PENGENALAN MUKIM KAWASAN L NO TELEFON 1 UST. HAJI MUSA BIN MUDA (710601-01-5539) 019-7545224 BANDAR -Pejabat Kadi Daerah Johor Bahru (ZON 1) 2 UST. FAKHRURAZI BIN YUSOF (791019-01-5805) 013-7270419 3 DATO’ HAJI MAHAT BIN BANDAR -Kg. Tarom -Tmn. Bkt. Saujana MD SAID (ZON 2) -Kg. Bahru -Tmn. Imigresen (360322-01-5539) -Kg. Nong Chik -Tmn. Bakti 07-2240567 -Kg. Mahmodiah -Pangsapuri Sri Murni 019-7254548 -Kg. Mohd Amin -Jln. Petri -Kg. Ngee Heng -Jln. Abd Rahman Andak -Tmn. Nong Chik -Jln. Serama -Tmn. Kolam Air -Menara Tabung Haji -Kolam Air -Dewan Jubli Intan -Jln. Straits View -Jln. Air Molek 4 UST. MOHD SHUKRI BIN BANDAR -Kg. Kurnia -Tmn. Melodies BACHOK (ZON 3) -Kg. Wadi Hana -Tmn. Kebun Teh (780825-01-5275) -Tmn. Perbadanan Islam -Tmn. Century 012-7601408 -Tmn. Suria 5 UST. AYUB BIN YUSOF BANDAR -Kg. Melayu Majidee -Flat Stulang (771228-01-6697) (ZON 4) -Kg. Stulang Baru 017-7286801 1 NAMA JURUNIKAH BI NO KAD PENGENALAN MUKIM KAWASAN L NO TELEFON 6 UST. MOHAMAD BANDAR - Kg. Dato’ Onn Jaafar -Kondo Datin Halimah IZUDDIN BIN HASSAN (ZON 5) - Kg. Aman -Flat Serantau Baru (760601-14-5339) - Kg. Sri Paya -Rumah Pangsa Larkin 013-3352230 - Kg. Kastam -Tmn. Larkin Perdana - Kg. Larkin Jaya -Tmn. Dato’ Onn - Kg. Ungku Mohsin 7 UST. HAJI ABU BAKAR BANDAR -Bandar Baru Uda -Polis Marin BIN WATAK (ZON 6) -Tmn. Skudai Kanan -Kg. -

Ujian Bertulis Sesi 1 Jawatan Pembantu Tadbir (P/O) Gred

UJIAN BERTULIS SESI 1 JAWATAN PEMBANTU TADBIR (P/O) GRED N19 TARIKH : 25 FEBRUARI 2018 MASA : 9.00 pagi – 10.00 pagi TEMPAT : INSTITUT PERGURUAN TUN HUSSIN ONN KM 7.75 JALAN KLUANG 83000 BATU PAHAT Bil Alamat & No. Telefon 1. Aatikah Binti Abdul Karim No 19 Jalan Maju 2 Taman Bakri Maju 84200 Muar 2. Abddul Rahman Bin Mohd Samsudin No 13 Jalan Gemilang 2/4 Taman Banang Jaya 83000 Batu Pahat Johor 3. Abdul Alim Bin Azlin No 442 Jalan Parit Masjid 83100 Rengit Batu Pahat 4. Abdul Aziim Bin Azmei 243 Jalan Parit Latif 83100 Rengit Johor 5. Abdul Rashid Bin Zulkipli No 7 Kampung Parit Lapis Simpang 3 83500 Parit Sulong Batu Pahat Johor 6. Abdul Rauf Bin Rahimee No 44 Jalan Nagaria Utama Taman Nagaria 83200 Senggarang Batu Pahat 7. Abdul Sattar Bin Mohd Kadis No 67 A Jalan Parit Imam Off Jalan Kluang 83000 Batu Pahat Johor 8. Abdur Rahman Bin Jamil 12 Jalan Jorak Ilahi Bukit Pasir 83000 Batu Pahat Johor 9. Adibah Binti Ismail Pos 151 Km 5 Bukit Treh Jalan Salleh 84000 Muar Johor 10. Adil Mazreen Bin Maznin No 10 Jalan Rambutan Taman Pantai 83000 Batu Pahat Johor 11. Aedel Haeqal Bin Abd Halim H-3-8 Pangsapuri Palma Jalan Palma Raja 3/KS 6 Bandar Botanik 41200 Klang Selangor 12. 910303-01-6126 Affariza Alia Binti Hj Affandi 07-5562976/019-7897353 No. 347 Jalan Baung Kampung Baru 81300 Skudai 13. 951124-01-5102 Affira Farra Ain Binti Sahazan Amir 07-4342606/011-16198658 No 34 Jalan Perdana 26A Taman Bukit Perdana 83000 Batu Pahat Johor 14. -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

Senarai Bilangan Pemilih Mengikut Dm Sebelum Persempadanan 2016 Johor

SURUHANJAYA PILIHAN RAYA MALAYSIA SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : JOHOR SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : JOHOR BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN : SEGAMAT BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : BULOH KASAP KOD BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : 140/01 SENARAI DAERAH MENGUNDI DAERAH MENGUNDI BILANGAN PEMILIH 140/01/01 MENSUDOT LAMA 398 140/01/02 BALAI BADANG 598 140/01/03 PALONG TIMOR 3,793 140/01/04 SEPANG LOI 722 140/01/05 MENSUDOT PINDAH 478 140/01/06 AWAT 425 140/01/07 PEKAN GEMAS BAHRU 2,391 140/01/08 GOMALI 392 140/01/09 TAMBANG 317 140/01/10 PAYA LANG 892 140/01/11 LADANG SUNGAI MUAR 452 140/01/12 KUALA PAYA 807 140/01/13 BANDAR BULOH KASAP UTARA 844 140/01/14 BANDAR BULOH KASAP SELATAN 1,879 140/01/15 BULOH KASAP 3,453 140/01/16 GELANG CHINCHIN 671 140/01/17 SEPINANG 560 JUMLAH PEMILIH 19,072 SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : JOHOR BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN : SEGAMAT BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : JEMENTAH KOD BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : 140/02 SENARAI DAERAH MENGUNDI DAERAH MENGUNDI BILANGAN PEMILIH 140/02/01 GEMAS BARU 248 140/02/02 FORTROSE 143 140/02/03 SUNGAI SENARUT 584 140/02/04 BANDAR BATU ANAM 2,743 140/02/05 BATU ANAM 1,437 140/02/06 BANDAN 421 140/02/07 WELCH 388 140/02/08 PAYA JAKAS 472 140/02/09 BANDAR JEMENTAH BARAT 3,486 140/02/10 BANDAR JEMENTAH TIMOR 2,719 140/02/11 BANDAR JEMENTAH TENGAH 414 140/02/12 BANDAR JEMENTAH SELATAN 865 140/02/13 JEMENTAH 365 140/02/14 -

Mewaholeo Industries, Pasir Gudang, Year of 2020

Mewaholeo Industries, Pasir Gudang, Year of 2020 CPO Traceability to Mill Declaration Document Processing Refinery: Mewaholeo Industries Sdn Bhd, Pasir Gudang, Johor Refinery Address: PLO 283, Jalan Besi Satu, Pasir Gudang Industrial Estate, 81700 Pasir Gudang, Johor, Malaysia. GPS Coordinate: 1.446539, 103.902672 Delivery Mode: Lorry Tanker Delivery Period: January - June 2020 (a.) Local Peninsular Malaysia CPO - Delivery Mode: Lorry Tanker *Receiving Percentage No Universe Mill List ID Parent Company's Name Mill's Name Mill Address Latitude Longitude (%) ACHI JAYA PLANTATIONS JOHOR LABIS PALM OIL MILL 1 PO1000003713 Lot 677,Mukim Chaah,85400 Segamat ,Johor . 2.25147 103.05131 0.55% SDN BHD SDN BHD BANDUNG PALM OIL BANDUNG PALM OIL Batu 1,Jln Gambir,Kangkar Senangar 83500 Parit Sulong 2 PO1000003718 2.04555 102.87980 5.10% INDUSTRIES SDN BHD INDUSTRIES SDN BHD Batu Pahat,Johor SYARIKAT PERUSAHAAN 3 PO1000003721 BELL GROUP SDN BHD Batu 9 ¾ Jln Labis 83700 Yong Peng 2.16697 103.05845 2.42% KELAPA SAWIT SDN BHD BELL PALM INDUSTRIES SDN Lot 4910-4911,Parit Ju,Mukim 4,Simpang Kiri,83000 Batu 4 PO1000003724 BELL GROUP SDN BHD 1.91678 102.89175 1.51% BHD Pahat,Johor 5 PO1000003863 BELL GROUP SDN BHD KKS BINTANG Batu 6,Jalan Paloh /Yong Peng ,Batu Pahat 2.15744 103.12343 1.78% BOUSTEAD PLANTATIONS KILANG KELAPA SAWIT TELOK 6 PO1000003738 Johor Lama, KOTA Tinggi ,Johor 1.56693 104.04494 1.77% BERHAD SENGAT BOUSTEAD PLANTATIONS KILANG KELAPA SAWIT SUNGAI KM 71,Lebuhraya Kuantan/Segamat ,Mukim Bebar Pekan 7 PO1000000338 3.33383 103.10011 0.12% BERHAD -

JOHOR P = Parlimen / Parliament N = Dewan Undangan Negeri (DUN)

JOHOR P = Parlimen / Parliament N = Dewan Undangan Negeri (DUN) KAWASAN / STATE PENYANDANG / INCUMBENT PARTI / PARTY P140 SEGAMAT SUBRAMANIAM A/L K.V SATHASIVAM BN N14001 - BULOH KASAP NORSHIDA BINTI IBRAHIM BN N14002 - JEMENTAH TAN CHEN CHOON DAP P141 SEKIJANG ANUAR BIN ABD. MANAP BN N14103 – PEMANIS LAU CHIN HOON BN N14104 - KEMELAH AYUB BIN RAHMAT BN P142 LABIS CHUA TEE YONG BN N14205 – TENANG MOHD AZAHAR BIN IBRAHIM BN N14206 - BEKOK LIM ENG GUAN DAP P143 PAGOH MAHIADDIN BIN MD YASIN BN N14307 - BUKIT SERAMPANG ISMAIL BIN MOHAMED BN N14308 - JORAK SHARUDDIN BIN MD SALLEH BN P144 LEDANG HAMIM BIN SAMURI BN N14409 – GAMBIR M ASOJAN A/L MUNIYANDY BN N14410 – TANGKAK EE CHIN LI DAP N14411 - SEROM ABD RAZAK BIN MINHAT BN P145 BAKRI ER TECK HWA DAP N14512 – BENTAYAN CHUA WEE BENG DAP N14513 - SUNGAI ABONG SHEIKH IBRAHIM BIN SALLEH PAS N14514 - BUKIT NANING SAIPOLBAHARI BIN SUIB BN P146 MUAR RAZALI BIN IBRAHIM BN N14615 – MAHARANI MOHD ISMAIL BIN ROSLAN BN N14616 - SUNGAI BALANG ZULKURNAIN BIN KAMISAN BN P14 7 PARIT SULONG NORAINI BINTI AHMAD BN N14717 – SEMERAH MOHD ISMAIL BIN ROSLAN BN N14718 - SRI MEDAN ZULKURNAIN BIN KAMISAN BN P148 AYER HITAM WEE KA SIONG BN N14819 - YONG PENG CHEW PECK CHOO DAP N14820 - SEMARANG SAMSOLBARI BIN JAMALI BN P149 SRI GADING AB AZIZ BIN KAPRAWI BN N14921 - PARIT YAANI AMINOLHUDA BIN HASSAN PAS N14922 - PARIT RAJA AZIZAH BINTI ZAKARIA BN P150 BATU PAHAT MOHD IDRIS BIN JUSI PKR N15023 – PENGGARAM GAN PECK CHENG DAP N15024 – SENGGARANG A.AZIZ BIN ISMAIL BN N15025 - RENGIT AYUB BIN JAMIL BN P151 SIMPANG RENGGAM LIANG TECK MENG BN N15126 – MACHAP ABD TAIB BIN ABU BAKAR BN N15127 - LAYANG -LAYANG ABD. -

1/3/2018 UUK Penjaja (MPPG)

17 NEGERI JOHOR Warta Kerajaan DITERBITKAN DENGAN KUASA GOVERNMENT OF JOHORE GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Jil. 62 TAMBAHAN No. 4 No. 5 1hb Mac 2018 PERUNDANGAN J. P.U. 6. ORDINAN KUMPULAN WANG PERUSAHAAN GETAH (PENANAMAN SEMULA) 1952 [Bilangan 8 Tahun 1952] PERATURAN-PERATURAN PIHAK BERKUASA KEMAJUAN PEKEBUN KECIL PERUSAHAAN GETAH (SKIM NO. 6) 1981 PADA menjalankan kuasa yang diberikan oleh perenggan 8 Peraturan-Peraturan Pihak Berkuasa Kemajuan Pekebun Kecil Perusahaan Getah (Skim No. 6) 1981, Saya Daman Huri bin Toha, Pengarah RISDA Negeri Johor dengan ini memberitahu notis bahawa ‘Daftar Permohonan-Permohonan Untuk Bantuan- Bantuan Tanam Semula Kebun-Kebun Kecil Getah’ bagi tahun 2018 akan dibuka mulai pada 1 Januari 2018 dan ditutup pada 31 Disember 2018. 2. Permohonan-permohonan hendaklah dibuat dalam borang yang ditentukan yang boleh didapati daripada mana-mana alamat yang berikut: (i) Pejabat Pengarah RISDA Negeri Johor PTB 12328 Jalan Padi Murni, Karung Berkunci 797, 81200 Johor Bahru (ii) Pejabat-Pejabat RISDA Daerah Pontian, Muar, Segamat, Kota Tinggi/ Johor Bahru/Kulai, Batu Pahat, Kluang dan Mersing; atau (iii) Pejabat-Pejabat RISDA Stesen Daerah Pontian (St. Pontian Utara dan St. Pontian Selatan), Daerah Muar/Ledang (St. Parit Jawa, St. Lenga, St. Bukit Gambir, St. Pagoh dan St. Tangkak) Daerah Segamat (St. Buloh Kasap, St. Labis, St. Jementah dan St. Tengah) Daerah Kota Tinggi/Johor Bahru/Kulaijaya (St. Bandar Penawar, St. Kota Tinggi dan St. Kulaijaya) Daerah Batu Pahat (St. Yong Peng, St. Parit Raja dan St. Sri Medan/Parit Sulong) Daerah Kluang (St. Sri Lalang, St. Simpang Renggam dan St. Kahang) Daerah Mersing (St. Mersing dan St. -

Alamat 1. Abdul Rahman Bin Abu Talib No. 11 A, Jalan Gunung Soga

JUMLAH - 275 BIL. Alamat 1. Abdul Rahman Bin Abu Talib No. 11 A, Jalan Gunung Soga, 83000 Batu Pahat, Johor. 2. Abdul Razee Bin Ab Kadir Pos 19, Kampung Sri Bengkal Laut, Mukim 6, Sri Gading, 83300 Batu Pahat, Johor. 3. Abdur Rahman Bin Jamil 12, Jalan Jorak Ilahi, Bukit Pasir, 83000 Batu Pahat, Johor. 4. Ahmad Asmuri Bin Hj Satim No. 10, Kampung Parit Gantung, Mukim 7, 86400 Parit Raja, Batu Pahat 5. Al Nazirul Mubin Bin Mohamad Hassim Pos 23 Kampung Parit Perpat Laut, 83100 Rengit, Batu Pahat 6. Aqid Danial Bin Hermie 5453, Jaaln Matahari 34/6, Bandar Indahpura, 81000 Kulai, Johor. 7. Arif Amali Bin Rozali No. 1, Jalan Dato Syed Zain, Kampung Bentong Dalam, 86000 Kluang, Johor. 8. Azlan Bin Bahari D 33, Kampung Parit Mohamad, 83500 Parit Sulong, Batu Pahat 9. Faizal Bin Mastuki No. 35, Jaaln Rumbia, Taman Datok Abdul Rahman Jaafar, 83000 Batu Pahat, Johor. 10. Harian Alimi Bin Tugi No. 3, Lorong Kt, Kampung Parit Warijo, Mukim 18, Sri Medan, 83400 Batu Pahat 11. Imran Norade Bin M. Zaine No. 42, Kampung Sungai Dulang Laut, 83100 Rengit, Batu Pahat, Johor. 12. Khairul Azim Bin Muhammad C2-11, No. 11, Tingkat 2, Blok C, Rumah Pangsa Pesta, 83000 Batu Pahat, Johor. 13. Khairuzzaman Bin Kemin Pos 43 Kampung Parit Bengkok, Sri Gading, 83300 Batu Pahat, Johor. 14. Masnor Bin Jemaan No. 1, Jalan Manis 19, Taman Manis 2, 86400 Parit Raja, Batu Pahat 15. Mohamad Afiq Azrul Bin Misran No. 144 B, Kampung Seri Belahan Tampok, 83100 Rengit, Johor. 16. Mohamad Ainul Azam Bin Zainal No. -

2021 Part 4 Northern Victorian Arms Collectors

NORTHERN VICTORIAN ARMS COLLECTORS GUILD INC. More Majorum 2021 PART 4 Bob Semple tank Footnote in History 7th AIF Battalion Lee–Speed Above Tiger 2 Tank Left Bob Sample Tank 380 Long [9.8 x 24mmR] Below is the Gemencheh Bridge in 1945 Something from your Collection William John Symons Modellers Corner by '' Old Nick '' Repeating Carbine Model 1890 Type 60 Light Anti-tank Vehicle Clabrough & Johnstone .22 rimfire conversion of a Lee-Speed carbine On the Heritage Trail by Peter Ford To the left some water carers at Gallipoli Taking Minié rifle rest before their next trip up. Below painting of the light horse charge at the Nek Guild Business N.V.A.C.G. Committee 2020/21 EXECUTIVE GENERAL COMMITTEE MEMBERS President/Treasurer: John McLean John Harrington Vice Pres/M/ship Sec: John Miller Scott Jackson Secretary: Graham Rogers Carl Webster Newsletter: Brett Maag Peter Roberts Safety Officer: Alan Nichols Rob Keen Sgt. at Arms: Simon Baxter Sol Sutherland Attention !! From the Secretary’S deSk Wanted - The name of the member who in mid-June, made a direct deposit of $125.00 cash into our bank account. I assume that person would like a current membership card, but as you have provided no clues as to who you are, all I can do is include you in the group that received their Annual Subscription Final Notice. Annual Subscriptions - At the time of writing we have 137 fully paid-up members, though one of them is ID unknown. For those that have yet to respond to the final notice, I am still happy to take your money at any time, but I won’t be posting any more reminders, you won’t have a membership card to cover you for Governor in Council Exemptions for Swords Daggers and Replica Firearms and we can’t endorse your firearms license applications or renewals. -

Parit Sulong Bridge Massacre

Parit Sulong Bridge Massacre Warning: This blog contains details of the horrors of war that some may find confronting. The barbarism of the Imperial Japanese Army had no bounds. When the Japanese invaded Malaya on the 8th December 1941, their overwhelming numbers, mobility with the use of bicycles, light tanks and air superiority, ensured their victory as they made their way south to Singapore. Their speed was such that in some cases, allied soldiers became surrounded or overrun and had no choice but to surrender thinking that they would be protected. But the Japanese policy of taking no prisoners to avoid being slowed down ensured that most would be quickly executed after capture. One such incident occurred at the bridge at Parit Sulong in Southern Malaya. On the 15th January 1942, the Japanese were approaching Muar on the south-west coast of Malaya, defended by the 45th Indian Malayan Peninsula Brigade. An Indian patrol encountered some Japanese nearby and withdrew but failed to inform their commanders of the Japanese presence. By noon, and without the Muar Garrison realizing, an entire Japanese division was on the outskirts. Fierce fighting erupted resulting in most of the officers being killed leaving the Indian soldiers leaderless. Australian artillery managed to stop a landing by Japanese in the harbour. To add to the problems of the 45th Brigade, a Japanese airstrike of the 45th Brigade’s headquarters killed most of the staff and injured the brigade commander. As a result, command of the 45th Brigade was temporarily handed over to Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Anderson, the commander of the Australian 2/19th Battalion. -

Making Malaysian Chinese

MAKING MALAYSIAN CHINESE: WAR MEMORY, HISTORIES AND IDENTITIES A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 FRANCES TAY SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Contents Introduction.............................................................................................................. 14 Identity: The Perennial Question ........................................................................ 16 Memory-Work and Identity Construction ............................................................ 17 Silence as a Concept .......................................................................................... 22 Multiple Wars, Multiple Histories......................................................................... 26 Ambiguous Histories, Simplifying Myths ............................................................. 30 Analytic Strategy and Methods ........................................................................... 34 Chapter 1. Historical Context: Chinese as Other .................................................... 38 Heaven-sent Coolies .......................................................................................... 39 Jews of the East.................................................................................................. 41 Irredentists and Subversives .............................................................................. 44 Overseas Chinese Compatriots .........................................................................