The Chinese Revolution on the Tibetan Frontier: State Building, National Integration And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Location: Tibet Lies at the Centre of Asia, with an Area of 2.5 Million Square Kilometers. the Earth's Highest Mountains, a Vast

Location: Tibet lies at the centre of Asia, with an area of 2.5 million square kilometers. The earth's highest mountains, a vast arid plateau and great river valleys make up the physical homeland of 6 million Tibetans. It has an average altitude of 13,000 feet above sea level. Capital: Lhasa Population: 6 million Tibetans and an estimated 7.5 million Chinese, most of whom are in Kham and Amdo. Language: Tibetan (of the Tibeto-Burmese language family). The official language is Chinese. Tibet is comprised of the three provinces of Amdo (now split by China into the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu & Sichuan), Kham (largely incorporated into the Chinese provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan and Qinghai), and U-Tsang (which, together with western Kham, is today referred to by China as the Tibet Autonomous Region). The Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) comprises less than half of historic Tibet and was created by China in 1965 for administrative reasons. It is important to note that when Chinese officials and publications use the term "Tibet" they mean only the TAR. Tibetans use the term Tibet to mean the three provinces described above, i.e., the area traditionally known as Tibet before the 1949-50 invasion. Today Tibetans are outnumbered by Han Chinese population in their own homeland, there are est. 6 million Tibetans and an estimated 7.5 million Chinese, most of whom are in Kham and Amdo. The official language is Chinese. But those Tibetans living in exile still speak, read and write in Tibetan (of the Tibeto-Burmese language family). -

Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians

138th IPU ASSEMBLY AND RELATED MEETINGS Geneva, 24 – 28.03.2018 Governing Council CL/202/11(b)-R.2 Item 11(b) Geneva, 28 March 2018 Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians Report on the mission to Mongolia 11 - 13 September 2017 MNG01 - Zorig Sanjasuuren Table of contents A. Origin and conduct of the mission ................................................................ 4 B. Outline of the case and the IPU follow up action ........................................... 5 C. Information gathered during the mission ...................................................... 7 D. Findings and recommendations further to the mission ................................ 15 E. Recent developments ................................................................................... 16 F. Observations provided by the authorities ..................................................... 17 G. Observations provided the complainant ....................................................... 26 H. Open letter of one of the persons sentenced for the murder of Zorig, recently published in the Mongolian media ................................................................ 27 * * * #IPU138 Mongolia © Zorig Foundation Executive Summary From 11 to 13 September 2017, a delegation of the Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians (hereinafter “the Committee”) conducted a mission to Mongolia to obtain further information on the recently concluded judicial proceedings that led to the final conviction of the three accused for the 1998 assassination of Mr. Zorig -

Dangerous Truths

Dangerous Truths The Panchen Lama's 1962 Report and China's Broken Promise of Tibetan Autonomy Matthew Akester July 10, 2017 About the Project 2049 Institute The Project 2049 Institute seeks to guide decision makers toward a more secure Asia by the century’s mid-point. Located in Arlington, Virginia, the organization fills a gap in the public policy realm through forward-looking, region-specific research on alternative security and policy solutions. Its interdisciplinary approach draws on rigorous analysis of socioeconomic, governance, military, environmental, technological and political trends, and input from key players in the region, with an eye toward educating the public and informing policy debate. About the Author Matthew Akester is a translator of classical and modern literary Tibetan, based in the Himalayan region. His translations include The Life of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, by Jamgon Kongtrul and Memories of Life in Lhasa Under Chinese Rule by Tubten Khetsun. He has worked as consultant for the Tibet Information Network, Human Rights Watch, the Tibet Heritage Fund, and the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center, among others. Acknowledgments This paper was commissioned by The Project 2049 Institute as part of a program to study "Chinese Communist Party History (CCP History)." More information on this program was highlighted at a conference titled, "1984 with Chinese Characteristics: How China Rewrites History" hosted by The Project 2049 Institute. Kelley Currie and Rachael Burton deserve special mention for reviewing paper drafts and making corrections. The following represents the author's own personal views only. TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Image: Mao Zedong (centre), Liu Shaoqi (left) meeting with 14th Dalai Lama (right 2) and 10th Panchen Lama (left 2) to celebrate Tibetan New Year, 1955 in Beijing. -

Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule

TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A COMPILATION OF REFUGEE STATEMENTS 1958-1975 A SERIES OF “EXPERT ON TIBET” PROGRAMS ON RADIO FREE ASIA TIBETAN SERVICE BY WARREN W. SMITH 1 TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A Compilation of Refugee Statements 1958-1975 Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule is a collection of twenty-seven Tibetan refugee statements published by the Information and Publicity Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1976. At that time Tibet was closed to the outside world and Chinese propaganda was mostly unchallenged in portraying Tibet as having abolished the former system of feudal serfdom and having achieved democratic reforms and socialist transformation as well as self-rule within the Tibet Autonomous Region. Tibetans were portrayed as happy with the results of their liberation by the Chinese Communist Party and satisfied with their lives under Chinese rule. The contrary accounts of the few Tibetan refugees who managed to escape at that time were generally dismissed as most likely exaggerated due to an assumed bias and their extreme contrast with the version of reality presented by the Chinese and their Tibetan spokespersons. The publication of these very credible Tibetan refugee statements challenged the Chinese version of reality within Tibet and began the shift in international opinion away from the claims of Chinese propaganda and toward the facts as revealed by Tibetan eyewitnesses. As such, the publication of this collection of refugee accounts was an important event in the history of Tibetan exile politics and the international perception of the Tibet issue. The following is a short synopsis of the accounts. -

Big Love: Mandala Magazine Article

LAMA YESHE, PASHUPATINATH TEMPLE, NEPAL, 1980. PHOTO BY TOM CASTLES, COURTESY OF LAMA YESHE WISDOM ARCHIVE. 26 MANDALA | July - December 2019 A MONUMENTAL ACCOMPLISHMENT: THE MAKING OF Big Love BY LAURA MILLER The creation of FPMT founder Lama Yeshe’s official biography has been a monumental task. Work on the forthcoming book, Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe, has spanned three decades. To understand the significance of this project as it draws to a close, Mandala talked to three key people, all early students of Lama Yeshe, about the production of the book: Adele Hulse, Big Love’s author; Peter Kedge, who initiated and helped fund the project; and Nicholas Ribush, who is overseeing the book’s publication at the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe begins with a refugee Tibetan monks. Together, the two lamas encountered their simple dedication: “This book is dedicated to you, the reader. first Western student, Zina Rachevsky, in 1967 in Darjeeling. The If you met Lama during your life, may you feel his presence here. following year, they went to Nepal, where they soon established If you never met Lama, then come with us—walk up the hill to Kopan Monastery on the outskirts of Kathmandu and later Kopan and meet Lama Yeshe, as thousands did, without knowing founded the international FPMT organization. anything of Buddhism or Tibet. That came later.” “Since then, His Holiness the Dalai Lama has been to many Within the biography’s nearly 1,400 pages, Lama Yeshe comes countries and now has a great reputation and has received many to life. -

LAW of MONGOLIA ORGANIC FOOD LAW of MONGOLIA 07 April, 2016 Ulaanbaatar City

LAW OF MONGOLIA ORGANIC FOOD LAW OF MONGOLIA 07 April, 2016 Ulaanbaatar city ORGANIC FOOD CHAPTER ONE General provisions Article 1 . Purpose 1.1. The purpose of this law is to regulate all aspects on organic agriculture, production of organic food, feed and fertilizer, their certification, trade, import, use of organic logo and advertisement. Article 2. The legislation on organic food 2.1. Legislation on organic food consists of the Constitution of Mongolia[l], Law on food[2], Law on food safety[3], Law on natural plants[4], Law on Forestry[5], Law on Standardization and Accreditation[6], Law on phytosani tary control of animal and plant originated products and raw materials at the border[7], and this law, and other legislative acts issued in conformity with all. 2.2. If an international treaty to which Mongolia is party states in different way, the provisions of international treaty shall prevail. Article 3. Scope 3.1. This law shall apply to agricultural originated organic food, unprocessed raw materials and products, natural plant originated organic food, organic feed, organic fertilizer and seed and seedlings. 3.2. This law shall not apply to produce food from raw materials of wild animals, and regulate activities of the public food. 17 Article 4. Definitions 4.1. The following terms, which used in this law shall be interpreted as follows: 4.1.1."organic food" is that given in 3.1.5 in Law on Food; 4.1.2."organic production" means to enterprise organic agricultural production of primary and food processing compliant with the requirements established in this Law; 4.1.3. -

Zootaxa, New Species of Phrynocephalus

Zootaxa 1988: 61–68 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) New species of Phrynocephalus (Squamata, Agamidae) from Qinghai, Northwest China XIANG JI1, 2 ,4, YUE-ZHAO WANG3 & ZHENG WANG1 1Jiangsu Key Laboratory for Biodiversity and Biotechnology, College of Life Sciences, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing 210046, Jiangsu, China 2Hangzhou Key Laboratory for Animal Sciences and Technology, School of Life Sciences, Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou 310036, Zhejiang, China 3Chengdu Institute of Biology, Academy of Sciences, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan, China 4Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected]; Tel: +86-25-85891597; Fax: +86-25-85891526 Abstract A new viviparous species of Phrynocephalus from Guinan, Qinghai, China, is described. Phrynocephalus guinanensis sp. nov., differs from all congeners in the following combination of characters: body large and relatively robust; dorsal ground color of head, neck, trunk, limbs and tail brown with weak light brown mottling; lateral ground color of head, neck, trunk and tail light black with weak white-gray mottling in adult males, and green with weak white-gray mottling in adult females; ventral ground color of tail white-gray to black in the distal part of the tail in adult males, and totally white-gray in adult females; ventral surfaces of hind-limbs white-gray; ventral surfaces of fore-limbs brick-red in adult males, and white-gray in adult females; ventral ground color of trunk and head black in the center but, in the periphery, brick-red in adult males and white-gray in adult females. -

China's NOTES from the EDITORS 4 Who's Hurting Who with National Culture

—Inspired by the Lei Feng* spirit of serving the people, primary school pupils of Harbin City often do public cleanups on their Sunday holidays despite severe winter temperature below zero 20°C. Photo by Men Suxian * Lei Feng was a squad leader of a Shenyang unit of the People's Liberation Army who died on August 15, 1962 while on duty. His practice of wholeheartedly serving the people in his ordinary post has become an example for all Chinese people, especially youfhs. Beijing««v!r VOL. 33, NO. 9 FEB. 26-MAR. 4, 1990 Carrying Forward the Cultural Heritage CONTENTS • In a January 10 speech. CPC Politburo member Li Ruihuan stressed the importance of promoting China's NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 Who's Hurting Who With national culture. Li said this will help strengthen the coun• Sanctions? try's sense of national identity, create the wherewithal to better resist foreign pressures, and reinforce national cohe• EVENTS/TRENDS 5 8 sion (p. 19). Hong Kong Basic Law Finalized Economic Zones Vital to China NPC to Meet in March Sanctions Will Get Nowhere Minister Stresses Inter-Ethnic Unity • Some Western politicians, in defiance of the reahties and Dalai's Threat Seen as Senseless the interests of both China and their own countries, are still Farmers Pin Hopes On Scientific demanding economic sanctions against China. They ignore Farming the fact that sanctions hurt their own interests as well as 194 AIDS Cases Discovered in China's (p. 4). China INTERNATIONAL Upholding the Five Principles of Socialism Will Save China Peaceful Coexistence 9 Mandela's Release: A Wise Step o This is the first instalment of a six-part series contributed Forward 13 by a Chinese student studying in the United States. -

The History and Politics of Taiwan's February 28

The History and Politics of Taiwan’s February 28 Incident, 1947- 2008 by Yen-Kuang Kuo BA, National Taiwan Univeristy, Taiwan, 1991 BA, University of Victoria, 2007 MA, University of Victoria, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of History © Yen-Kuang Kuo, 2020 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee The History and Politics of Taiwan’s February 28 Incident, 1947- 2008 by Yen-Kuang Kuo BA, National Taiwan Univeristy, Taiwan, 1991 BA, University of Victoria, 2007 MA, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Zhongping Chen, Supervisor Department of History Dr. Gregory Blue, Departmental Member Department of History Dr. John Price, Departmental Member Department of History Dr. Andrew Marton, Outside Member Department of Pacific and Asian Studies iii Abstract Taiwan’s February 28 Incident happened in 1947 as a set of popular protests against the postwar policies of the Nationalist Party, and it then sparked militant actions and political struggles of Taiwanese but ended with military suppression and political persecution by the Nanjing government. The Nationalist Party first defined the Incident as a rebellion by pro-Japanese forces and communist saboteurs. As the enemy of the Nationalist Party in China’s Civil War (1946-1949), the Chinese Communist Party initially interpreted the Incident as a Taiwanese fight for political autonomy in the party’s wartime propaganda, and then reinterpreted the event as an anti-Nationalist uprising under its own leadership. -

Lessons Learned from China's Solar Policies

Lessons learned from China’s solar policies: Implications for Southeast Asia Dr Sam Geall chinadialogue [email protected] April 2019, Wilson Center 19th Party Congress, 2017: the “Driver’s Seat”? • In 3+ hours, Xi’s speech had 89 mentions of ‘environment,’ just 70 of the ‘economy’ • China now “is in the driver’s seat” on climate cooperation • Poverty alleviation focus: “Down-to-earth, adaption to local conditions, classified guidance and targeted poverty alleviation” China’s 13th Five Year Plan (2016-2020) • The “new normal”: from investment-led to consumer-led growth, innovation and services • “Ecological civilization”: focus on green policies and technologies • Energy efficiency, promotion of renewables and reduction of coal in the energy mix: 18% reduction in carbon intensity from 2015 levels by 2020 • 15% reduction in energy intensity • 15% of primary energy from non fossil sources • Reduce energy consumption below 5 billion tonnes of standard coal equivalent by 2020 Top Five Countries Annual Investment/Capacity Additions /Production in 2016 Source: REN21 2017 China’s solar industry boom • Crisis in 2010 led to government intervention; • Domestic market boom between 2010 and 2015; • 15GW installed in 2015 alone; • Hit the ceiling when power grid has no capacity for accommodation and transmission; • Curtailment reaches 50% in some areas in early 2016; • Distributed system favored by government but not by private investors Why renewables for development? • Renewable energy technologies: • help to mitigate climate change • provide cheap and reliable energy to areas where grid-based provision is unreliable or otherwise prohibited by geography or high costs • improve energy availability, energy security and economic resilience. -

Qinghai WLAN Area 1/13

Qinghai WLAN area NO. SSID Location_Name Location_Type Location_Address City Province 1 ChinaNet Quality Supervision Mansion Business Building No.31 Xiguan Street Xining City Qinghai Province No.160 Yellow River Road 2 ChinaNet Victory Hotel Conference Center Convention Center Xining City Qinghai Province 3 ChinaNet Shangpin Space Recreation Bar No.16-36 Xiguan Street Xining City Qinghai Province 4 ChinaNet Business Building No.372 Qilian Road Xining City Qinghai Province Salt Mansion 5 ChinaNet Yatai Trade City Large Shopping Mall Dongguan Street Xining City Qinghai Province 6 ChinaNet Gome Large Shopping Mall No.72 Dongguan Street Xining City Qinghai Province 7 ChinaNet West Airport Office Building Business Building No.32 Bayi Road Xining City Qinghai Province Government Agencies 8 ChinaNet Chengdong District Government Xining City Qinghai Province and Other Institutions Delingha Road 9 ChinaNet Junjiao Mansion Business Building Xining City Qinghai Province Bayi Road Government Agencies 10 ChinaNet Higher Procuratortate Office Building Xining City Qinghai Province and Other Institutions Wusi West Road 11 ChinaNet Zijin Garden Business Building No.41, Wusi West Road Xining City Qinghai Province 12 ChinaNet Qingbai Shopping Mall Large Shopping Mall Xining City Qinghai Province No.39, Wusi Avenue 13 ChinaNet CYTS Mansion Business Building No.55-1 Shengli Road Xining City Qinghai Province 14 ChinaNet Chenxiong Mansion Business Building No.15 Shengli Road Xining City Qinghai Province 15 ChinaNet Platform Bridge Shoes City Large Shopping -

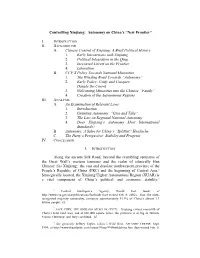

Controlling Xinjiang: Autonomy on China's “New Frontier”

Controlling Xinjiang: Autonomy on China’s “New Frontier” I. INTRODUCTION II. BACKGROUND A. Chinese Control of Xinjiang: A Brief Political History 1. Early Interactions with Xinjiang 2. Political Integration in the Qing 3. Increased Unrest on the Frontier 4. Liberation B. CCP’S Policy Towards National Minorities 1. The Winding Road Towards “Autonomy” 2. Early Policy: Unify and Conquer: Dangle the Carrot 3. Welcoming Minorities into the Chinese “Family” 4. Creation of the Autonomous Regions III. ANALYSIS A. An Examination of Relevant Laws 1. Introduction 2. Granting Autonomy: “Give and Take” 3. The Law on Regional National Autonomy 4. Does Xinjiang’s Autonomy Meet International Standards? B. Autonomy: A Salve for China’s “Splittist” Headache C. The Party’s Perspective: Stability and Progress IV. CONCLUSION I. INTRODUCTION Along the ancient Silk Road, beyond the crumbling remnants of the Great Wall’s western terminus and the realm of ethnically Han Chinese1 lies Xinjiang: the vast and desolate northwestern province of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the beginning of Central Asia.2 Strategically located, the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (XUAR) is a vital component of China’s political and economic stability.3 1 Central Intelligence Agency, World Fact Book, at http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook (last visited Feb. 8, 2002). Han, the state- recognized majority nationality, comprise approximately 91.9% of China’s almost 1.3 billion people. Id. 2 JACK CHEN, THE SINKIANG STORY xx (1977). Xinjiang covers one-sixth of China’s total land area, and at 660,000 square miles, the province is as big as Britain, France, Germany, and Italy combined.