Some Thoughts on Writing and Reviewing Scientific Articles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biosafety and Health

BIOSAFETY AND HEALTH AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.1 • Editorial Board p.1 • Guide for Authors p.6 ISSN: 2590-0536 DESCRIPTION . Biosafety and Health is an open access, peer-reviewed journal sponsored by the Chinese Medical Association, managed by National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC). This journal aims to publish original research findings and thoughts in any aspect connected with public health and biosafety. Topics include but are not limited to: Identification and characterization of biological threats; Origin, transmission, and evolution of biological agents; Surveillance, risk assessment, and early-warning; Prevention, diagnosis, and therapeutics; Synthetic biotechnology, genome editing, and other new biotechniques; Biosafety materials; Policies and standards. Biosafety and Health is published bimonthly in English language. Article types include Original Research, Reviews, Perspectives, Correspondence, Case Report, News and Views, Highlights, Comments and policy forum, etc. ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING . Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) Scopus EDITORIAL BOARD . Editor-in-Chief Guizhen Wu, National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China Research on the prevention and control of infectious diseases, in addiiton to the treatment and traceability of major emergency infectious diseases, Research on the management of laboratory biosafety. Executive Editor-in-Chief -

Future Science Group Catalogue 2020

Header Future Science Group Catalogue 2020 1 Section Header 2 For more information visit www.future-science-group.com Contents Page Our Journal Portfolio 2 ........................................................................................................................................ Future Medicine At-A-Glance 3 ........................................................................................................................................ Future Science and Newlands Press At-A-Glance 4 ........................................................................................................................................ eBook Collections 4 ........................................................................................................................................ New to Future Science Group 5 ........................................................................................................................................ Information for Librarians 6 ........................................................................................................................................ Institutional Trials 7 ........................................................................................................................................ Digital Hubs 8 ........................................................................................................................................ Sponsorship Opportunities 9 ....................................................................................................................................... -

Complaint Alleges That OMICS Group, Inc., Along with Two Affiliated Companies

Case 2:16-cv-02022 Document 1 Filed 08/25/16 Page 1 of 54 1 DAVID C. SHONKA Acting General Counsel 2 IOANA RUSU GREGORY A. ASHE 3 Federal Trade Commission 4 600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20850 5 Telephone: 202-326-2077 (Rusu) Telephone: 202-326-3719 (Ashe) 6 Facsimile: 202-326-3768 7 Email: [email protected], [email protected] 8 DANIEL G. BOGDEN United States Attorney 9 BLAINE T. WELSH 10 Assistant United States Attorney Nevada Bar No. 4790 11 333 Las Vegas Blvd. South, Suite 5000 Las Vegas, Nevada 89101 12 Phone: (702) 388-6336 13 Facsimile: (702) 388-6787 14 Attorneys for Plaintiff 15 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 16 DISTRICT OF NEVADA 17 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION, 18 Case No. 2:16-cv-02022 Plaintiff, 19 COMPLAINT FOR PERMANENT v. INJUNCTION AND OTHER 20 EQUITABLE RELIEF OMICS GROUP INC., a Nevada corporation, 21 also d/b/a OMICS Publishing Group, IMEDPUB 22 LLC, a Delaware corporation, CONFERENCE SERIES LLC, a Delaware corporation, and 23 SRINUBABU GEDELA, 24 Defendants. 25 26 Plaintiff, the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”), for its Complaint alleges: 27 28 Page 1 of 16 Case 2:16-cv-02022 Document 1 Filed 08/25/16 Page 2 of 54 1 1. The FTC brings this action under Section 13(b) of the Federal Trade Commission Act 2 (“FTC Act”), 15 U.S.C. § 53(b) to obtain permanent injunctive relief, rescission or 3 reformation of contracts, restitution, the refund of monies paid, disgorgement of ill-gotten 4 monies, and other equitable relief for Defendants’ acts or practices in violation of 5 Section 5(a) of the FTC Act, 15 U.S.C. -

![A Workflow Using Open Access Tools and Concepts [Version 1; Peer Review: 1 Approved, 1 Approved with Reservations]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9350/a-workflow-using-open-access-tools-and-concepts-version-1-peer-review-1-approved-1-approved-with-reservations-6419350.webp)

A Workflow Using Open Access Tools and Concepts [Version 1; Peer Review: 1 Approved, 1 Approved with Reservations]

F1000Research 2020, 9:1373 Last updated: 01 OCT 2021 SOFTWARE TOOL ARTICLE Effective image visualization for publications – a workflow using open access tools and concepts [version 1; peer review: 1 approved, 1 approved with reservations] Christopher Schmied 1*, Helena Klara Jambor 2* 1Leibniz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie im Forschungsverbund Berlin e.V. (FMP), Berlin, Germany 2Mildred-Scheel Early Career Center, Medical Faculty, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany * Equal contributors v1 First published: 26 Nov 2020, 9:1373 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.27140.1 Latest published: 18 Feb 2021, 9:1373 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.27140.2 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract Today, 25% of figures in biomedical publications contain images of 1 2 various types, e.g. photos, light or electron microscopy images, x-rays, or even sketches or drawings. Despite being widely used, published version 2 images may be ineffective or illegible since details are not visible, (revision) report information is missing or they have been inappropriately processed. 18 Feb 2021 The vast majority of such imperfect images can be attributed to the lack of experience of the authors as undergraduate and graduate version 1 curricula lack courses on image acquisition, ethical processing, and 26 Nov 2020 report report visualization. Here we present a step-by-step image processing workflow for effective and ethical image presentation. The workflow is aimed to 1. Guillaume Jacquemet , University of allow novice users with little or no prior experience in image Turku, Turku, Finland processing to implement the essential steps towards publishing images. The workflow is based on the open source software Fiji, but 2. -

Catalogue 2021

Header Future Science Group Catalogue 2021 1 Section Header 2 For more information visit www.future-science-group.com Contents Page Our Journal Portfolio 2 ........................................................................................................................................ Future Medicine At-A-Glance 3 ........................................................................................................................................ Future Science and Newlands Press At-A-Glance 4 ........................................................................................................................................ eBook Collections 4 ........................................................................................................................................ New to Future Science Group 5 ........................................................................................................................................ Information for Librarians 6 ........................................................................................................................................ Institutional Trials 7 ........................................................................................................................................ Digital Hubs 8 ........................................................................................................................................ Sponsorship Opportunities 9 ....................................................................................................................................... -

Future Science Group Catalogue 2019

Header Future Science Group Catalogue 2019 Contact us Future Science Group Unitec House 2 Albert Place London, N3 1QB United kingdom +44(0)20 8371 6090 [email protected] [email protected] www.future-science-group.com @futuresciencegp future-science-group Future Science Group 1 Section Header 2 For more information visit www.future-science-group.com Contents Page Our Journal Portfolio 2 ........................................................................................................................................ Future Medicine At-A-Glance 3 ........................................................................................................................................ Future Science and Newlands Press At-A-Glance 4 ........................................................................................................................................ eBook Collections 4 ........................................................................................................................................ New to Future Science 5 ........................................................................................................................................ Information for Librarians 6 ........................................................................................................................................ Institutional Trials 7 ........................................................................................................................................ Digital -

Journal List of Scopus.Xlsx

Sourcerecord id Source Title (CSA excl.) (Medline-sourced journals are indicated in Green). Print-ISSN Including Conference Proceedings available in the scopus.com Source Browse list 16400154734 A + U-Architecture and Urbanism 03899160 5700161051 A Contrario. Revue interdisciplinaire de sciences sociales 16607880 19600162043 A.M.A. American Journal of Diseases of Children 00968994 19400157806 A.M.A. archives of dermatology 00965359 19600162081 A.M.A. Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology 00965979 19400157807 A.M.A. archives of industrial health 05673933 19600162082 A.M.A. Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Occupational Medicine 00966703 19400157808 A.M.A. archives of internal medicine 08882479 19400158171 A.M.A. archives of neurology 03758540 19400157809 A.M.A. archives of neurology and psychiatry 00966886 19400157810 A.M.A. archives of ophthalmology 00966339 19400157811 A.M.A. archives of otolaryngology 00966894 19400157812 A.M.A. archives of pathology 00966711 19400157813 A.M.A. archives of surgery 00966908 5800207606 AAA, Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik 01715410 28033 AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication 07434618 50013 AACE International. Transactions of the Annual Meeting 15287106 19300156808 AACL Bioflux 18448143 4700152443 AACN Advanced Critical Care 15597768 26408 AACN clinical issues 10790713 51879 AACN clinical issues in critical care nursing 10467467 26729 AANA Journal 00946354 66438 AANNT journal / the American Association of Nephrology Nurses and Technicians 07441479 5100155055 AAO Journal 27096 AAOHN -

Scientific Publication Workshop

Pre-Congress Workshop HW6 Scientific Publication: Reading, Writing, and Reviewing John M. Butler, Ph.D. NIST Fellow & Special Assistant to the Director for Forensic Science U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology Associate Editor, Forensic Science International: Genetics 10 September 2019 Acknowledgments and Disclaimer Points of view are mine and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Standards and Technology or of Forensic Science International: Genetics or the Journal of Forensic Sciences (where I serve on editorial boards). Certain commercial entities are identified in order to specify experimental procedures as completely as possible. In no case does such identification imply a recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor does it imply that any of the entities identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose. Value of Studying this Topic “Without publication, science is dead.” http://www.rolexawards.com/FILE/5069.jpg Gerard Piel (1915 – 2004) Publisher of Scientific American magazine “A scientific experiment is not complete until the results have been published and understood.” - Robert A. Day Some Topics We Hope to Address • How to find the best articles to answer my questions or to strengthen my research efforts • How to gain the most from articles that I read • How to store articles that I collect so I can find them again • How to review or become a better peer-reviewer • How to write or to improve my writing -

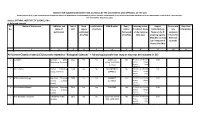

Science Citation Index (SCI) Journals Related to "Biological Sciences" + Following Journals That May Or May Not Be Included in SCI

FORMAT FOR SUBJECTWISE IDENTIFYING JOURNALS BY THE UNIVERSITIES AND APPROVAL OF THE UGC {Under Clause 6.05 (1) of the University Grants Commission (Minimum Qualifications for appointment of Teacher and Other Academic Staff in Universities and Colleges and Measures for the Maintenance of Standards in Higher Education (4th Amendment), Regulations, 2016} Subject: BOTANY, INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE, BHU A. Refereed Journals Sl. Name of the Journal Publisher and Year of Hard e-publication ISSN Number Peer / Indexing status. Impact Do you use Any other No. place of Start copies (Yes/No) Refree If indexed, Name Factor/Rating. any Information publication published Reviewed of the indexing Name of the IF exclusion (Yes/No) (Yes/No) data base assigning agency. criteria for Whether covered Research by Thompson & Journals Reuter (Yes/No) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 All Science Citation Index (SCI) Journals related to "Biological Sciences" + following journals that may or may not be included in SCI 1 3 Biotech Springer Berlin 2011 Yes Yes 2190-572X Yes Thomson and Router, 0.99 Heidelberg, Germany (Print) 2190-5738 Scopus, Google (Online) Scholar, Cross reference 2 AACL Bioflux Bioflux Publishing 2009 Yes Yes ISSN 18448143, Yes Thomson and Router, 0.5 House, Romania 18449166 Scopus, Google Scholar, Cross reference 3 ACS Chemical biology American Chemical 2006 Yes Yes 15548937, Yes Thomson and Router, 5.02 Society (United 15548929 Scopus, Google States) Scholar, Cross reference 4 ACS Synthetic Biology American Chemical 2012 Yes Yes 21615063 Yes Thomson and Router, 4.56 Society (United Scopus, Google States) Scholar, Cross reference 5 Acta Biologica Hungarica Akadémiai Kiadó, 1873 Yes Yes 0236-6495 Online Yes Thomson and Router, 0.97 Hungary ISSN: 1588-2578 Scopus, Google Scholar, Cross reference Sl.