Revised Version 12 March 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brighton City Airport (Shoreham) Heritage Assessment March 2016

Brighton City Airport (Shoreham) Heritage Assessment March 2016 Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Setting, character and designations 3 3. The planning context 5 4. The history of the airfield to 1918 7 5. The end of the First World War to the outbreak of the Second 10 6. The Second World War 13 7. Post-war history 18 8. The dome trainer and its setting 20 9. The airfield as the setting for historical landmarks 24 10 Significance 26 11. Impacts and their effects 33 12. Summary and conclusions 40 13. References 42 Figures 1. The proposed development 2. The setting of the airfield 3. The view northwards from the airfield to Lancing College 4. Old Shoreham Bridge and the Church of St Nicolas 5. The view north eastwards across the airfield to Old Shoreham 6. Principal features of the airfield and photograph viewpoints 7. The terminal building, municipal hangar and the south edge of the airfield 8. The tidal wall looking north 9. The railway bridge 10. The dome trainer 11. The north edge and north hangar 12. The airfield 1911-1918 13. The 1911 proposals 14. The airfield in the 1920s and 1930s 15. The municipal airport proposal 16. Air photograph of 1936 17. Airfield defences 1940-41 18. Air photograph, November 1941 19. Map of pipe mines 20. Air photograph, April 1946 21. Air Ministry drawing, 1954 22. The airfield in 1967 23. Post-war development of the south edge of the airfield 24. Dome trainer construction and use 25. Langham dome trainer interior 26. Langham dome trainer exterior 27. -

St Eval PCC Report & Accounts Year Ending 31St December 2020

St Eval PCC Report & Accounts Year ending 31st December 2020 Incumbent The Reverend HelenBaber Curate, The Reverend Tess Lowe PCC members who have served during 2020 until the date this report was approved are: Rector & Chair The Reverend Helen Baber Deputy Chair (Lay) Mrs. Joanna Scoffham Churchwardens: Mrs. Sandra Backway Mrs. Rosalie Moncaster Treasurer & Mr. Christopher Moncaster Gift Aid Officer Health and Safety Mr Christopher Moncaster Safeguarding Mrs Joanna Scoffham (Children) Secretary Mr Jeremy Stuart Electoral Roll Officer Mrs. Sandra Backway Elected Mrs. Sandra Backway Members Mrs. Pat Kent Mrs. Gillian Lovegrove Mrs. Shirley Osborne Mrs. Joanna Scoffham Mr. Richard Wilson Reverend Andrew Turner (from October 2020) The method of appointment of PCC members is set out in the Church Representation Rules. All church Attendees are encouraged to register on the Electoral Roll and stand for election to the PCC. The PCC met twice during the year. St. Eval PCC has the responsibility of co-operating with the incumbent in promoting the whole mission of the church, pastoral, evangelistic, social and ecumenical in the ecclesiastical parish. It also has maintenance responsibilities for the church, churchyard, church room, toilet block and grounds. The Parochial Church Council (PCC) is a charity excepted from registration with the Charity Commission. The church is part of the Diocese of Truro within the Church of England and is one of the four churches in the Lann Pydar Benefice. The other Parishes are St. Columb Major, St. Ervan and St. Mawgan-in-Pydar. The Parish Office, which is shared with the other 3 churches within the benefice, has now been relocated to the Rectory in St Columb Major. -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

Bibliomara: an Annotated Indexed Bibliography of Cultural and Maritime Heritage Studies of the Coastal Zone in Ireland

BiblioMara: An annotated indexed bibliography of cultural and maritime heritage studies of the coastal zone in Ireland BiblioMara: Leabharliosta d’ábhar scríofa a bhaineann le cúltúr agus oidhreacht mara na hÉireann (Stage I & II, January 2004) Max Kozachenko1, Helen Rea1, Valerie Cummins1, Clíona O’Carroll2, Pádraig Ó Duinnín3, Jo Good2, David Butler1, Darina Tully3, Éamonn Ó Tuama1, Marie-Annick Desplanques2 & Gearóid Ó Crualaoich 2 1 Coastal and Marine Resources Centre, ERI, UCC 2 Department of Béaloideas, UCC 3 Meitheal Mara, Cork University College Cork Department of Béaloideas Abstract BiblioMara: What is it? BiblioMara is an indexed, annotated bibliography of written material relating to Ireland’s coastal and maritime heritage; that is a list of books, articles, theses and reports with a short account of their content. The index provided at the end of the bibliography allows users to search the bibliography using keywords and authors’ names. The majority of the documents referenced were published after the year 1900. What are ‘written materials relating to Ireland’s coastal heritage’? The BiblioMara bibliography contains material that has been written down which relates to the lives of the people on the coast; today and in the past; their history and language; and the way that the sea has affected their way of life and their imagination. The bibliography attempts to list as many materials as possible that deal with the myriad interactions between people and their maritime surroundings. The island of Ireland and aspects of coastal life are covered, from lobster pot making to the uses of seaweed, from the fate of the Spanish Armada to the future of wave energy, from the sailing schooner fleets of Arklow to the County Down herring girls, from Galway hookers to the songs of Tory Islanders. -

Victory! Victory Over Japan Day Is the Day on Which Japan Surrendered in World War II, in Effect Ending the War

AugustAAuugugusstt 201622001166 BRINGING HISTORY TO LIFE See pages 24-26! Victory! Victory over Japan Day is the day on which Japan surrendered in World War II, in effect ending the war. The term has been applied to both of the days on which the initial announcement of Japan’s surrender was made – to the afternoon of August 15, 1945, in Japan, and, because of time zone differences, to August 14, 1945. AmericanAmerican servicemenservicemen andand womenwomen gathergather inin frontfront ofof “Rainbow“Rainbow Corner”Corner” RedRed CrossCross clubclub inin ParisParis toto celebratecelebrate thethe unconditionalunconditional surrendersurrender ofof thethe Japanese.Japanese. 1515 AugustAugust 19451945 Over 200 NEW & RESTOCK Items Inside These Pages! • PLASTICPPLAASSSTTIIC MODELM KITS • MODEL ACCESSORIES • BOOKS & MAGAZINES • PAINTS & TOOLS • GIFTS & COLLECTIBLES See back cover for full details. Order Today at WWW.SQUADRON.COM or call 1-877-414-0434 August Cover Version 1.indd 1 7/7/2016 1:02:36 PM Dear Friends One of the most important model shows this year is taking place in Columbia, South Carolina in August…The IPMS Nationals. SQUADRON As always, the team from Squadron will be there to meet you. We look forward to this event because it gives us a chance to PRODUCTS talk to you all in person. It is the perfect time to hear any sugges- tions you might have so we can serve you even better. If you are at the Nationals, please stop by our booth to say hello. We can’t wait to meet you and hear all about your hobby experi- ences. On top of that, you’ll receive a Squadron shopping bag NEW with goodies! Our booth number is 819. -

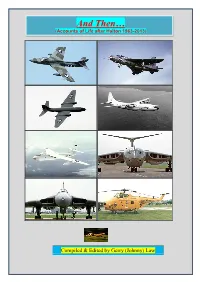

And Then… (Accounts of Life After Halton 1963-2013)

And Then… (Accounts of Life after Halton 1963-2013) Compiled & Edited by Gerry (Johnny) Law And Then… CONTENTS Foreword & Dedication 3 Introduction 3 List of aircraft types 6 Whitehall Cenotaph 249 St George’s 50th Anniversary 249 RAF Halton Apprentices Hymn 251 Low Flying 244 Contributions: John Baldwin 7 Tony Benstead 29 Peter Brown 43 Graham Castle 45 John Crawford 50 Jim Duff 55 Roger Garford 56 Dennis Greenwell 62 Daymon Grewcock 66 Chris Harvey 68 Rob Honnor 76 Merv Kelly 89 Glenn Knight 92 Gerry Law 97 Charlie Lee 123 Chris Lee 126 John Longstaff 143 Alistair Mackie 154 Ivor Maggs 157 David Mawdsley 161 Tony Meston 164 Tony Metcalfe 173 Stuart Meyers 175 Ian Nelson 178 Bruce Owens 193 Geoff Rann 195 Tony Robson 197 Bill Sandiford 202 Gordon Sherratt 206 Mike Snuggs 211 Brian Spence 213 Malcolm Swaisland 215 Colin Woodland 236 John Baldwin’s Ode 246 In Memoriam 252 © the Contributors 2 And Then… FOREWORD & DEDICATION This book is produced as part of the 96th Entry’s celebration of 50 years since Graduation Our motto is “Quam Celerrime (With Greatest Speed)” and our logo is that very epitome of speed, the Cheetah, hence the ‘Spotty Moggy’ on the front page. The book is dedicated to all those who joined the 96th Entry in 1960 and who subsequently went on to serve the Country in many different ways. INTRODUCTION On the 31st July 1963 the 96th Entry marched off Henderson Parade Ground marking the conclusion of 3 years hard graft, interspersed with a few laughs. It also marked the start of our Entry into the big, bold world that was the Royal Air Force at that time. -

Raaf Personnel Serving on Attachment in Royal Air Force Squadrons and Support Units in World War 2 and Missing with No Known Grave

Cover Design by: 121Creative Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6012 email. [email protected] www.121creative.com.au Printed by: Kwik Kopy Canberra Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6066 email. [email protected] www.canberra.kwikkopy.com.au Compilation Alan Storr 2006 The information appearing in this compilation is derived from the collections of the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia. Author : Alan Storr Alan was born in Melbourne Australia in 1921. He joined the RAAF in October 1941 and served in the Pacific theatre of war. He was an Observer and did a tour of operations with No 7 Squadron RAAF (Beauforts), and later was Flight Navigation Officer of No 201 Flight RAAF (Liberators). He was discharged Flight Lieutenant in February 1946. He has spent most of his Public Service working life in Canberra – first arriving in the National Capital in 1938. He held senior positions in the Department of Air (First Assistant Secretary) and the Department of Defence (Senior Assistant Secretary), and retired from the public service in 1975. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree (Melbourne University) and was a graduate of the Australian Staff College, ‘Manyung’, Mt Eliza, Victoria. He has been a volunteer at the Australian War Memorial for 21 years doing research into aircraft relics held at the AWM, and more recently research work into RAAF World War 2 fatalities. He has written and published eight books on RAAF fatalities in the eight RAAF Squadrons serving in RAF Bomber Command in WW2. -

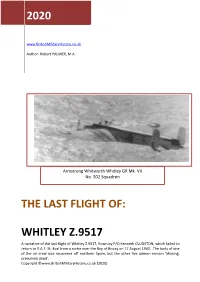

The Last Flight of Whitley Z.9517, Flown by P/O Kenneth CLUGSTON, Which Failed to Return to R.A.F

2020 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. Armstrong Whitworth Whitley GR Mk. VII No. 502 Squadron THE LAST FLIGHT OF: WHITLEY Z.9517 A narrative of the last flight of Whitley Z.9517, flown by P/O Kenneth CLUGSTON, which failed to return to R.A.F. St. Eval from a sortie over the Bay of Biscay on 17 August 1942. The body of one of the air crew was recovered off northern Spain, but the other five airmen remain ‘Missing, presumed dead’. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2020) 13 July 2020 [THE LAST FLIGHT OF WHITLEY Z.9517] The Last Flight of Whitley Z.9517 Version: V3_7 This edition dated: 13 July 2020 ISBN: Not yet allocated. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means including; electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, scanning without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. (copyright held by author); Researcher: Stephen HEAL, David HOWELLS & Graham MOORE. Published privately by: The Author – Publishing as: www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk The Air Forces’ Memorial at Cooper’s Hill, Runnymede, Surrey. This memorial contains the names of 20,279 British and Commonwealth air crew who were lost in the Second World War, and have no known grave. https://www.cwgc.org/find/find-cemeteries-and-memorials/109600/runnymede-memorial 1 13 July 2020 [THE LAST FLIGHT OF WHITLEY Z.9517] Contents Chapter Pages Introduction 3 The Armstrong Whitworth Whitley 3 – 5 Operational History with Coastal Command 5 – 7 No. -

B-24 Liberator in Coastal Command (RAF) Service & Aircraft of No.311

B-24 Liberator in Coastal Command (RAF) Service & Aircraft of No.311 (Czechoslovak)Squadron RAF Pavel Türk, Miloslav Pajer 1. RAF Coastal Command Coastal Command přestalo existovat 27.11.1969, kdy se stalo součástí RAF Strike Command. Dne 1.dubna 1918 vzniklo Royal Air Force sloučením Royal Flying Corps a Royal Naval Air Service. Pro Admiralitu to znamenalo, že musela předat Délka operační túry u perutí Pobřežního letectva zaměřených na námořní/ všechna svá letadla a převést personál pod kontrolu RAF. Vedení Admira- protiponorkové hlídkové lety byla stanovena na 18 měsíců nebo 800 leto- lity tuto organizační změnu přijalo s nevolí a následujících 20 let bylo bu- vých hodin, podle toho, co nastalo dříve. dování námořních perutí RAF poznamenáno snahou Admirality o získání opětovné kontroly nad „svým“ letectvem. Velitelé RAF Coastal Command: Po svém ustanovení procházelo RAF jednou reorganizací za druhou. K 1. květnu 1918 byly zformovány jako hlavní organizační složky tzv. Are- Air Marshal Sir Arthur Longmore 14. červenec 1936 - 1. září 1936 as. Nejprve byly číslovány, ale záhy obdržely zeměpisné názvy odpovídající Air Marshal Sir Philip Joubert de la Ferte 1. září 1936 - 18. srpen 1937 jejich umístění (např. South Western Area). V rámci Areas byly ustanoveny Air Marshal Sir Frederick Bowhill 18. srpen 1937 - 14. červen 1941 Skupiny (Groups), pod které spadaly základny a jednotky. Na konci listopa- Air Chief Marshal Sir Philip Joubert de la Ferte 14. červen 1941 - du 1918 existovalo v rámci pěti Areas deset námořních Groups. S koncem 5. únor 1943 1. světové války přišly další změny v organizaci. Byl zredukován jak počet Air Marshal Sir John Slessor 5. -

Defence Heritage Audit

Binevenagh Coast and Lowlands Defence Heritage Audit (for proposed Landscape Partnership Scheme) by quarto and Ulidia Heritage Services April 2017 Contents 1. Background to the report p3 2. Research methodologies p5 3. What is the defence heritage of the Binevenagh area? 3.1. Historical overview p12 3.2. Audit of defence heritage features p15 3.3. Threats to preservation p17 4. Why is the defence heritage of the Binevenagh area important? p21 5. How do people access, learn about and participate in Binevenagh’s defence heritage now? p24 6. What opportunities and barriers exist to improving access, learning and participation? 6.1. Public access p28 6.2. Community engagement p31 6.3. Education p32 7. Project proposals 7.1. Development phase p35 7.2. Delivery phase p40 Appendices Appendix A: case studies p49 Appendix B: summary of curricula links p55 Appendix C: potential stakeholder contacts p58 Appendix D: gazetteer p62 Appendix E: references p93 * Cover image: Limavady Airfield Air Training Dome (courtesy of Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council). 2 1. Background to the report The Causeway Coast and Glens Heritage Trust (CCGHT) promotes and develops the Causeway Coast and Glens area’s ‘scenic landscapes, important wildlife resources and… rich cultural heritage’. CCGHT encourages management of physical landscapes and their historical accretions with a view to sustainability and long-term benefit to local communities.1 CCGHT is responsible for managing the Antrim Coast and Glens Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), Causeway Coast AONB and Binevenagh AONB. The Trust has delivered a successful Landscape Partnership Scheme in Antrim Coast and Glens AONB and is now developing a similar initiative in Binevenagh AONB. -

Newsletter Issue 11 Winter 2007

Newsletter Issue 11 Winter 2007 Cover Photos Top WF512 (44 Squadron) at dispersal, RAF Coningsby ( Ernest Howlett ) Bottom The Queen inspects the massed ranks of aircraft at the Coronation review. See page 20 for an alternative perspective on the Royal review by Douglas Cook who, by then, had swapped his Washington for a Shackleton. ( John (Buster) Crabbe ) This Page Bottom left Shot of the Control Tower, summer 1953.Note how close the Fire bay was to the Tower. Upper right: John Moore talking down a recalcitrant, American Major, in his Auster. At that stage Coningsby was in the throes of converting from B29s to Jets with the Jet Conversion unit in residence as shown on the board behind John. The other boards show 57, 15 and 44 Sqdns. Presumably 149 is on the hidden board! Note the old G.C.A still in use! ( Both photos John Moore ) . Chris Howlett The Barn Isle Abbotts Taunton Somerset TA3 6RS e-mail: [email protected] 1 Letters John Crabbe wrote : Thinking of your latest “Times” and just for laughs, thought I'd send you this shot taken with my wife's tiny camera - I think - in 1953 when my Mum and Dad visited us at Marham (In front of 'My' B29 – unfortunately the quality is not very good!) By now I'd left 207 via 35 and was now a Flt/Sgt Crew Chief on 115 Sqn. I actually flew back to the States with this A/C to its final resting place at Davis Monthan- The Captain on that occasion was one F/O Joe Locharane (May be miss-spelled) The rest of the crew as I remember were - Flt ? 'Goose neck' Nav. -

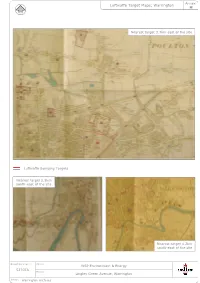

Annex Luftwaffe Target Maps; Warrington H

Annex Luftwaffe Target Maps; Warrington H North Nearest target 3.7km east of the site Luftwaffe Bombing Targets Nearest target 2.8km south-east of the site Nearest target 4.2km south-east of the site Report Reference: Client: WSP Environment & Energy 5270TA Project: Lingley Green Avenue, Warrington Source: Warrington Archives Annex Recent German UXB Find – RAF St. Eval I North Unexploded German SC50 HE Bomb found in a field immediately adjacent to the historic perimeter of RAF St. Eval, a WWII-era Fighter Command station in Cornwall. Report Reference: Client: WSP Environment & Energy 5270TA Project: Lingley Green Avenue, Warrington Source: BACTEC International Ltd Annex German Air-Delivered Ordnance High Explosive Bombs J SC 50 Bomb Weight: 40-54kg (110-119lb) Explosive Weight: c25kg (55lb) Fuze Type: Impact fuze/electro-mechanical time delay fuze Bomb Dimensions: 1,090 x 280mm (42.9 x 11.0in) Body Diameter: 200mm (7.87in) Use: Against lightly damageable materials, hangars, railway rolling stock, ammunition depots, light bridges and buildings up to three stories. 50kg bomb, London Docklands Remarks: The smallest and most common conventional German 400mm bomb. Nearly 70% of bombs dropped on the UK were 50kg. Minus tail section SC 250 Bomb weight: 245-256kg (540-564lb) Explosive weight: 125-130kg (276-287lb) Fuze type: Electrical impact/mechanical time delay fuze. Bomb dimensions: 1640 x 512mm (64.57 x 20.16in) Body diameter: 368mm (14.5in) Use: Against railway installations, embankments, flyovers, underpasses, large buildings and below-ground installations. 250kg bomb, Hawkinge 1kg Incendiary Bomb 123 Bomb weight: 1.0 and 1.3kg (2.2 and 2.87lb) Filling: 680gm (1.3lb) Thermite Fuze type: Impact fuze Bomb dimensions: 350 x 50mm (13.8 x 1.97in) Body diameter: 50mm (1.97in) Use: As incendiary – dropped in clusters against towns and industrial complexes Remarks: Jettisoned from air-dropped containers.