For Review Only Land Transport, Traffic and Urbanisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNEX a List of Mosques Offering 3 Friday Prayers on 7 Aug 2020

ANNEX A List of mosques offering 3 Friday prayers on 7 Aug 2020 (1 p.m., 2 p.m. and 3 p.m.) Mosque Cluster 1. Masjid Al-Istighfar (2 Zones) 2. Masjid Abdul Aleem Siddique 3. Masjid Al Abdul Razak 4. Masjid Al-Ansar 5. Masjid Al-Islah 6. Masjid Alkaff Kampung Melayu 7. Masjid Al-Mawaddah 8. Masjid Al-Taqua 9. Masjid Darul Aman East 10. Masjid Darul Ghufran 11. Masjid Haji Mohd Salleh (Geylang) 12. Masjid Kampung Siglap 13. Masjid Kassim 14. Masjid Khalid 15. Masjid Mydin 16. Masjid Sallim Mattar 17. Masjid Wak Tanjong 18. Masjid Assyafaah (2 Zones) 19. Masjid Abdul Hamid (Kg Pasiran) 20. Masjid Ahmad Ibrahim 21. Masjid Al-Istiqamah 22. Masjid Al-Muttaqin 23. Masjid An-Nahdhah 24. Masjid An-Nur North 25. Masjid Darul Makmur 26. Masjid En-Naeem 27. Masjid Hajjah Rahimabi Kebun Limau 28. Masjid Muhajirin 29. Masjid Yusof Ishak 30. Masjid Haji Yusoff 31. Masjid Mujahidin (2 Zones) 32. Masjid Al-Amin 33. Masjid Al-Falah 34. Masjid Angullia 35. Masjid Haji Muhammad Salleh (Palmer) 36. Masjid Jamek Queenstown South 37. Masjid Jamiyah Ar-Rabitah 38. Masjid Kampong Delta 39. Masjid Malabar 40. Masjid Sultan 1 41. Masjid Al-Iman (2 Zones) 42. Masjid Ahmad 43. Masjid Al-Firdaus 44. Masjid Al-Huda 45. Masjid Al-Khair 46. Masjid Al-Mukminin 47. Masjid Ar-Raudhah West 48. Masjid Assyakirin 49. Masjid Darussalam 50. Masjid Hang Jebat 51. Masjid Hasanah 52. Masjid Maarof 53. Masjid Tentera Di Raja List of mosques offering 2 Friday Prayers on 7 Aug 2020 (1 p.m. -

Unique Entity Number for Mosques

MUI/MO/2 DID : 6359 1180 FAX: 6252 3235 MOSQUE CIRCULAR 014/08 27 November 2008 Chairman/Secretary Mosque Management Board Assalamualaikum wr wb Dear Sir UNIQUE ENTITY NUMBER FOR MOSQUES May you and your Board members and staff be in good health and continue to be showered with Allah SWT blessings. 2 The Singapore Government will introduce the Unique Entity Number (UEN) for registered entities on 1 January 2009 and mosques will be one of those issued with a UEN 3 UEN shall be for registered entities as NRIC is for Singapore citizens. The UEN uniquely identifies the mosque. Mosques will enjoy the convenience of having a single identification number for interaction with the Government, such as submitting their employees’ CPF contributions. 4 The list of UEN numbers for each mosque is attached in Annexe A. In situations where mosques are asked to provide their Business Registration Number (BRN) or Registry of Societies number, they may use their UEN number instead. 5 From 1 January 2009, 52 government agencies such as Central Provident Fund Board (CPFB) and Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS) will use UEN to interact with entities (both over-the-counter and online interactions). All other government agencies will use UEN from 1 July 2009. 6 For more information on the list of government agencies that will be using UEN and other details, please visit www.uen.gov.sg . You can also contact Muhd Taufiq at DID: 6359 1185 or email at [email protected] . Thank you and wassalam. Yours faithfully ZAINI OSMAN HEAD (MOSQUE DEVELOPMENT) MAJLIS -

Jadual Solat Aidilfitri Bahasa Bahasa Penyampaian Penyampaian No

JADUAL SOLAT AIDILFITRI BAHASA BAHASA PENYAMPAIAN PENYAMPAIAN NO. NAMA & ALAMAT MASJID WAKTU KHUTBAH NO. NAMA & ALAMAT MASJID WAKTU KHUTBAH KELOMPOK MASJID UTARA KELOMPOK MASJID TIMUR LOKASI WAKTU 1 Masjid Abdul Hamid Kg Pasiran, 10 Gentle Rd 8:00 pg Melayu 1 Masjid Al-Ansar, 155 Bedok North Avenue 1 8:00 pg Melayu DAERAH TIMUR 2 Masjid Ahmad Ibrahim, 15 Jln Ulu Seletar 7:45 pg Melayu 2 Masjid Al-Istighfar, 2 Pasir Ris Walk 7:35 pg Melayu 1 Dewan Serba guna Blk 757B, Pasir Ris St 71 8:00 pg 3 Masjid Alkaff Upper Serangoon, 8:00 pg Melayu 3 Masjid Darul Aman, 1 Jalan Eunos 8:30 pg Melayu 2 Kolong Blk 108 & 116, Simei Street 1 8:15 pg 66 Pheng Geck Avenue 9:30 pg Bengali 3 Kolong Blk 286, Tampines St 22 8:15 pg 4 Masjid Al-Istiqamah, 2 Serangoon North Avenue 2 8:00 pg Melayu 4 Masjid Alkaff Kampung Melayu, 8:00 pg Melayu 5 Masjid Al-Muttaqin, 5140 Ang Mo Kio Avenue 6 7:45 pg Melayu 4 Kolong Blk 450, Tampines St 42 8:00 pg 200 Bedok Reservoir Road 8:45 pg Inggeris 5 Dewan Serba guna Blk 498N, Tampines St 45 8:15 pg 5 Masjid Al-Mawaddah, 151 Compassvale Bow 8:00 pg Melayu 6 Masjid An-Nahdhah, No 9A Bishan St 14 8:00 pg Melayu 6 Kolong (Tingkat 2) Blk 827A, Tampines St 81 8:30 pg 6 Masjid Darul Ghufran, 503 Tampines Avenue 5 8:00 pg Melayu 7 Masjid An-Nur, 6 Admiralty Road 7:30 pg Melayu 7 Kolong Blk 898, Tampines St 81 8:15 pg 7 Masjid Haji Mohd Salleh (Geylang), 8:00 pg Melayu 8 Masjid Assyafaah, 1 Admiralty Lane 8:00 pg Melayu 8 Kolong Blk 847, Tampines St 83 8:00 pg 245 Geylang Road 9:00 pg Bengali 9.15 pg Bengali 9 Kolong Blk 924, Tampines -

Gazetting of New Designated Car-Lite Areas

Circular No : LTA/DBC/F20.033.005 Date : 22 Jun 2020 CIRCULAR TO PROFESSIONAL INSTITUTES Who should know Developers, building owners, tenants and Qualified Persons (QPs) Effective date 1 August 2020 GAZETTING OF NEW DESIGNATED CAR-LITE AREAS 1. In Nov 2018, LTA announced the new Range-based Parking Provision Standards (RPPS) and the new parking Zone 4 for car-lite areas, which came into force in Feb 2019. The areas classified as “Zone 4” in the RPPS will be planned with strong public transport connectivity, walking and cycling travel options. Vehicle parking provision for development applications within these areas will be determined by LTA on a case-specific basis. Five car-lite areas were gazetted on 1 Feb 2019. They are Kampong Bugis, Marina South, Jurong Lake District (JLD), Bayshore and Woodlands North. 2. The car-lite boundary of JLD will be expanded in view of the potential synergies between the JLD area gazetted as Zone 4 in Feb 2019 and the adjacent development areas. In addition, 5 new areas will be gazetted for development as car-lite areas. These are Jurong Innovation District (JID), one-north, Punggol Digital District (PDD), Springleaf, and Woodlands Central. Please refer to Appendix 1 for details on the boundaries of these car-lite areas. These 5 new car-lite areas and the expanded boundary of JLD will be gazetted as Zone 4 with effect from 1 Aug 2020. 3. The Zone 4 vehicle parking requirement will apply to all new development proposals within the car-lite areas highlighted in paragraph 2, submitted to LTA from 1 Aug 2020 onwards. -

From Tales to Legends: Discover Singapore Stories a Floral Tribute to Singapore's Stories

Appendix II From Tales to Legends: Discover Singapore Stories A floral tribute to Singapore's stories Amidst a sea of orchids, the mythical Merlion battles a 10-metre-high “wave” and saves a fishing village from nature’s wrath. Against the backdrop of an undulating green wall, a sorcerer’s evil plan and the mystery of Bukit Timah Hill unfolds. Hidden in a secret garden is the legend of Radin Mas and the enchanting story of a filial princess. In celebration of Singapore’s golden jubilee, 10 local folklore are brought to life through the creative use of orchids and other flowers in “Singapore Stories” – a SG50-commemorative floral display in the Flower Dome at Gardens by the Bay. Designed by award-winning Singaporean landscape architect, Damian Tang, and featuring more than 8,000 orchid plants and flowers, the colourful floral showcase recollects the many tales and legends that surround this city-island. Come discover the stories behind Tanjong Pagar, Redhill, Sisters’ Island, Pulau Ubin, Kusu Island, Sang Nila Utama and the Singapore Stone – as told through the language of plants. Along the way, take a walk down memory lane with scenes from the past that pay tribute to the unsung heroes who helped to build this nation. Date: Friday, 31 July 2015 to Sunday, 13 September 2015 Time: 9am – 9pm* Location: Flower Dome Details: Admission charge to the Flower Dome applies * Extended until 10pm on National Day (9 August) About Damian Tang Damian Tang is a multiple award-winning landscape architect with local and international titles to his name. -

Draft Master Plan 2013 Singapore ENVISIONING a GREAT CITY

Draft Master Plan 2013 Singapore ENVISIONING A GREAT CITY he Draft Master Plan 2013 is Singapore’s latest blueprint for T development over the next 10 – 15 years. Urban Redevelopment Authority Chief Planner Lim Eng Hwee explains it is the result of close inter-agency collaboration to support a vibrant economy and create a green, healthy and connected city for its residents. 01 With population growth, Singapore planners face new challenges, like strains on urban infrastructure. Draft 35 Master Plan case study The Challenge 2013 In January 2013, the Singapore government released its White Paper on Population, highlighting ENVISIONING the challenge of a shrinking and ageing resident population and A GREAT CITY the need to supplement it in order to sustain reasonable economic growth. Accompanying this White Paper was the Land Use Plan, which outlined broad strategies to support a population scenario of up to 6.9 million. Some of these strategies – development of our Now there are new significant land reserves, land reclamation challenges, including a diminishing and redevelopment of low-intensity land bank, rapid urbanisation land uses – address enduring and intensification, strain on our challenges such as land scarcity public transport system and other and growing land demand. infrastructure, and the public’s increasing desire to have a say in how we develop our future. For planners, these new challenges require innovative urban solutions that provide for a quality living environment while retaining Singapore’s unique social fabric and cultural roots. June 2014 June 2014 • • ISSUE 5 ISSUE 5 01 01 The Solution With the last Master Plan review envisioned the DMP13 as people- 01 An artist’s impression centric and relevant to the everyday of high-density yet undertaken in 2008, it was highly liveable and imperative that the latest Master concerns of residents. -

Lion City Adventures Secrets of the Heartlandsfor Review Only Join the Lion City Adventuring Club and Take a Journey Back in Time to C

don bos Lion City Adventures secrets of the heartlandsFor Review only Join the Lion City Adventuring Club and take a journey back in time to C see how the fascinating heartlands of Singapore have evolved. o s ecrets of the Each chapter contains a history of the neighbourhood, information about remarkable people and events, colourful illustrations, and a fun activity. You’ll also get to tackle story puzzles and help solve an exciting mystery along the way. s heA ArtL NDS e This is a sequel to the popular children’s book, Lion City Adventures. C rets of the he rets the 8 neighbourhoods feAtured Toa Payoh Yishun Queenstown Tiong Bahru Kampong Bahru Jalan Kayu Marine Parade Punggol A rt LA nds Marshall Cavendish Marshall Cavendish In association with Super Cool Books children’s/singapore ISBN 978-981-4721-16-5 ,!7IJ8B4-hcbbgf! Editions i LLustrAted don bos Co by shAron Lei For Review only lIon City a dventures don bosco Illustrated by VIshnu n rajan L I O N C I T Y ADVENTURING CLUB now clap your hands and repeat this loudly: n For Review only orth, south, east and west! I am happy to do my best! Editor: Melvin Neo Designer: Adithi Shankar Khandadi Illustrator: Vishnu N Rajan © 2015 Don Bosco (Super Cool Books) and Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Pte Ltd y ou, This book is published by Marshall Cavendish Editions in association with Super Cool Books. Reprinted 2016, 2019 ______________________________ , Published by Marshall Cavendish Editions (write your name here) An imprint of Marshall Cavendish International are hereby invited to join the All rights reserved lion city adventuring club No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval systemor transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, on a delightful adventure without the prior permission of the copyright owner. -

A City in and Through Time: the Mannahatta Project

ECOLOGY A City in and through Time: The Mannahatta Project Text and Images by Eric W. Sanderson Additional images as credited n September 12th, 1609, Henry Hudson 1 guided a small wooden vessel up the mighty O river that would one day be known by his name. On his right was a long, thin, wooded island, called by its inhabitants, Mannahatta. Four hundred years and some odd later, we know that same place as Manhattan. Today the island is densely filled with people and avenues as it was once with trees and streams. Where forests and wetlands once stood for millennia, skyscrapers and apartment buildings now pierce the sky. The screeching of tires and the wailing of sirens have replaced bird song and wolves howling at the moon. Extraordinary cultural diversity has replaced extraordinary biodiversity. In short, the transformation of Mannahatta into Manhattan typifies a global change of profound importance, the reworking of the Earth into cities made for men and women and the concomitant loss of memory about how truly glorious and abundant our world is. Mannahatta had more ecological communities per acre than Yellowstone, more native plant species per acre than Yosemite, and more birds than the Great Smoky Mountains, all National Parks in the United States today. Mannahatta housed wolves, black bears, mountain lions, beavers, mink, and river otters; whales, porpoises, seals, and the occasional sea turtle visited its harbor. Millions of birds of more than a hundred and fifty different species flew over the island annually on transcontinental migratory pathways; millions of fish—shad, herring, trout, sturgeon, and eel—swam past the island up the Hudson River and in its streams during annual rites of spring. -

PERSEPSI PENGUNJUNG TERHADAP MUSEUM SANG NILA UTAMA PEKANBARU OLEH : Anton Fareira T/1301114439 [email protected]

PERSEPSI PENGUNJUNG TERHADAP MUSEUM SANG NILA UTAMA PEKANBARU OLEH : Anton Fareira T/1301114439 [email protected] Pembimbing : Drs. Syafrizal, M.Si Jurusan Sosiologi Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Riau Kampus Bina Widya Jln. HR Soebrantas Km 12,5 Simpang Baru Panam Pekanbaru 28293 Telp/FAX 0761-63272 ABSTRAK Penelitian ini di lakukan di Museum Sang Nila Utama dijalan Jendral Sudirman No.194, Tangkerang Tengah, Marpoyan Damai, Kota Pekanbaru. Dengan rumusan masalah (1) Bagaimana kareteristik pengunjung Museum Sang Nila Utama Pekanbaru Riau? (2) bagaimana persepsi pengunjung terhadap kondisi fisik Museum Sang Nila Utama Pekanbaru ? (3) bagaimana hubungan antara persepsi pengunjung Museum terhadap kondisi fisik Museum dengan tingkat pemahaman pengunjung terhadap nilai sejarah koleksi Museum Sang Nila Utama Pekanbaru. Tujuan dari penelitian ini adalah untuk menganalisa karakteristik pengunjung Museum Sang Nila Utama Pekanbaru, untuk menganalisa persepsi pengunjung terhadap kondisi fisik Museum Sang Nila Utama Pekanbaru, dan untuk mengetahui hubungan antara persepsi pengunjung terhadap kondisi fisik museum dengan tingkat pemahaman pengunjung terhadap nilai sejarah koleksi Museum Sang Nila Utama Pekanbaru. Penelitian ini merupakan penelitian deskriptif dengan pendekatan kuantitatif. Populasi pada penelitian ini sebanyak 100.017 orang, lalu di gunakan salah satu teknik pengambilan sampel yaitu dengan menggunakan metode slovin, maka di dapat sampel sebanyak 99 orang, untuk mengumpulkan data penelitian ini di gunakan kuesioner dan dokumentasi. Berdasarkan hasil penelitian dapat disimpulkan bahwa (1) secara umum pengunjung Museum Sang Nila Utama sudah memanfaatkan fungsi Museum dengan baik, dari 99 responden terdapat 50 responden dengan persentase 58,6 % dengan kategori tinggi pada kegiatan formal, dan dari 99 responden terdapat 42 responden 71,2 % dengan kategori tinggi pada kegiatan non formal. -

Download Map and Guide

Bukit Pasoh Telok Ayer Kreta Ayer CHINATOWN A Walking Guide Travel through 14 amazing stops to experience the best of Chinatown in 6 hours. A quick introduction to the neighbourhoods Kreta Ayer Kreta Ayer means “water cart” in Malay. It refers to ox-drawn carts that brought water to the district in the 19th and 20th centuries. The water was drawn from wells at Ann Siang Hill. Back in those days, this area was known for its clusters of teahouses and opera theatres, and the infamous brothels, gambling houses and opium dens that lined the streets. Much of its sordid history has been cleaned up. However, remnants of its vibrant past are still present – especially during festive periods like the Lunar New Year and the Mid-Autumn celebrations. Telok Ayer Meaning “bay water” in Malay, Telok Ayer was at the shoreline where early immigrants disembarked from their long voyages. Designated a Chinese district by Stamford Raffles in 1822, this is the oldest neighbourhood in Chinatown. Covering Ann Siang and Club Street, this richly diverse area is packed with trendy bars and hipster cafés housed in beautifully conserved shophouses. Bukit Pasoh Located on a hill, Bukit Pasoh is lined with award-winning restaurants, boutique hotels, and conserved art deco shophouses. Once upon a time, earthen pots were produced here. Hence, its name – pasoh, which means pot in Malay. The most vibrant street in this area is Keong Saik Road – a former red-light district where gangs and vice once thrived. Today, it’s a hip enclave for stylish hotels, cool bars and great food. -

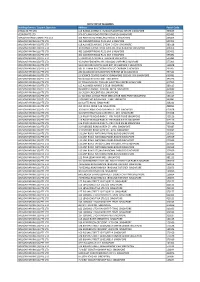

Building Owner / Carpark Operator Address Postal Code

NETS TOP UP MACHINES Building Owner / Carpark Operator Address Postal Code ZHAOLIM PTE LTD 115 EUNOS AVENUE 3 EUNOS INDUSTRIAL ESTATE SINGAPORE 409839 YESIKEN PTE LTD 970 GEYLANG ROAD TRISTAR COMPLEX SINGAPORE 423492 WINSLAND INVESTMENT PTE LTD 163 PENANG RD WINSLAND HOUSE II SINGAPORE 238463 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 461 CLEMENTI ROAD P121-SIM SINGAPORE 599491 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 118 ALJUNIED AVENUE 2 P204_2-GEM SINGAPORE 380118 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 30 ORANGE GROVE ROAD P203-REL RELC BUILDING SINGAPORE 258352 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 461 CLEMENTI ROAD P121-SIM SINGAPORE 599491 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 461 CLEMENTI ROAD P121-SIM SINGAPORE 599491 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 5 TAMPINES CENTRAL 6 TELEPARK SINGAPORE 529482 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 49 JALAN PEMIMPIN APS IND BLDG CARPARK SINGAPORE 577203 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD SGH CAR PARK BOOTH NEAR EXIT OF CARPARK C SINGAPORE 169608 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 587 BT TIMAH RD CORONATION S/C CARPARK SINGAPORE 269707 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 280 WOODLANDS INDUSTRIAL HARVEST @ WOODLANDS 757322 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 15 SCIENCE CENTRE ROAD SCI SINGAPORE SCIENCE CEN SINGAPORE 609081 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 56 CASSIA CRESCENT KM1 SINGAPORE 391056 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 19 TANGLIN ROAD TANGLIN SHOPPING CENTRE SINGAPORE 247909 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 115 ALJUNIED AVENUE 2 GE1B SINGAPORE 380115 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 89 MARINE PARADE CENTRAL MP19 SINGAPORE 440089 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 32 CASSIA CRESCENT K10 SINGAPORE 390032 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD -

JADUAL WAKTU SOLAT HARI RAYA EIDULFITRI DI MASJID-MASJID 17 Julai 2015 / 1 Syawal 1436H

JADUAL WAKTU SOLAT HARI RAYA EIDULFITRI DI MASJID-MASJID 17 Julai 2015 / 1 Syawal 1436H NO. NAMA & ALAMAT MASJID WAKTU BAHASA PENYAMPAIAN KHUTBAH Kelompok Masjid Tengah Utara 1 Masjid Abdul Hamid Kg Pasiran, 10 Gentle Rd 8.00 pg Melayu 2 Masjid Al-Muttaqin, 5140 Ang Mo Kio Avenue 6 7.45 pg Melayu 8.45 pg Inggeris Masjid Angullia, 265 Serangoon Road 7.30 pg Tamil 3 8.30 pg Bengali 9.00 pg Urdu 4 Masjid An-Nahdhah, No 9A Bishan St 14 8.00 pg Melayu 5 Masjid Ba'alwie, 2 Lewis Road 8.30 pg Melayu 6 Masjid Haji Mohd Salleh (Geylang), 245 Geylang Road 8.00 pg Melayu & Inggeris 9.00 pg Bengali 7 Masjid Hajjah Fatimah, 4001 Beach Road 8.00 pg Melayu 8 Masjid Hajjah Rahimabi, 76 Kim Keat Road 8.30 pg Melayu 9 Masjid Malabar, 471 Victoria Street 9.00 pg Inggeris, Arab, Malayalam & Urdu 10 Masjid Muhajirin, 275 Braddell Road 8.15 pg Melayu 11 Masjid Omar Salmah, 441B Jalan Mashor 8.15 pg Melayu 12 Masjid Sultan, 3 Muscat Street 8.30 pg Melayu 13 Masjid Tasek Utara, 46 Bristol Road 8.00 pg Melayu Kelompok Masjid Tengah Selatan 1 Masjid Abdul Gafoor, 41 Dunlop Street 7.30 pg Tamil & 8.30 pg 2 Masjid Al-Abrar (Koochoo Pally), 192 Telok Ayer Street 8.30 pg Tamil 3 Masjid Al-Amin, 50 Telok Blangah Way 8.00 pg Melayu 4 Masjid Al-Falah, Cairnhill Place #01-01, Bideford Road 8.15 pg Inggeris 5 Masjid Bencoolen, 51 Bencoolen St, #01-01 8.00 pg Tamil 6 Masjid Haji Muhammad Salleh (Palmer), 37 Palmer Road 8.15 pg Melayu & Inggeris 7 Masjid Jamae Chulia, 218 South Bridge Road 8.30 pg Tamil 8 Masjid Jamae Queenstown, 946 Margaret Drive 8.30 pg Melayu 9 Masjid Jamiyah Ar-Rabitah.