9789401475877.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17 May – BOZAR & the Colors of the Rainbow

17 May – BOZAR & The colors of the rainbow 1. Introduction: The Centre for Fine Arts, gender and LGBTIQ. (Lesbian, Gay, Bi-sexual, Trans-sexual, Intersex and Questioning). As part of its international mission, the Centre for Fine Arts Brussels (BOZAR) aims to show and establish exchange with cultures from all over the world, to promote cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue and to advocate the role of culture as a catalyst for creativity. BOZAR does not only show art for art’s sake. We believe in debate, and in the community building capacity of the arts. As a cultural organization with a large variety of artistic disciplines ranging from literature and music to discussion platforms, we have always strived to offer a programme that is highly ranked on an artistic level but at the same time widely accessible to our 1.3 million visitors per year. In doing so, the CFA aims to reflect the multi-cultural reality of the hyper-diverse city of Brussels. We have had the honour of welcoming personalities such as Salman Rushdie, Barack Obama and the Dalai Lama. Exceptional events like these have only solidified our involvement in social and political issues as well as our leading cultural role in Belgium. We aim to combine art and society to offer a nuanced vision. In 2014, the central Summer of Photography exhibition at the Centre for Fine Arts examined the role of female artists in the second wave of feminism, WOMAN: The Feminist Avant-Garde of the1970s: Works from the SAMMUNG VERBUND, Vienna curated by Gabriele Schor. -

The Great Indoors

The Great Indoors CATALOGUE SPRING 2018 Contents 2 New Titles Ceramic Design What I’ve Learned The Other Office 3 8 Previously Announced Grand Stand 6 Suppose Design Office Identity Architects Built Unbuilt 12 Recent Titles Jo Nagasaka / Schemata Architects Studio O+A Happening 2 Night Fever 5 16 Portfolio Highlights Where They Create Japan Sound Materials Powershop 5 Knowledge Matters Spaces for Innovation CMF Design Goods 2 Holistic Retail Design 20 Backlist 29 Index 30 Distributors 32 Contacts & Credits 2 NEW TITLES 3 CERAMIC DESIGN New Wave Clay The unprecedented surge in popularity of 44 Ceramic Design 45 Bruce Rowe By day, Bruce Rowe runs the Melbourne ceramics brand Anchor Ceramics, which produces handmade lighting, tiles and planters on an almost industrial scale, selling to homes, architects and the hospitality trade across Australia. Then Rowe swaps making ceramics for the built environment in order to make the built environment ceramics in the last five years has helped forge out of clay. The structures he creates are composed of architectural elements BRUCE assembled in strange compositions: constructions made of stairs, passageways, bridges and arches. They are never literal images of actual architecture, but creative interpretations with a De Chirico-like surreal quality. “The works do not directly reference any specific place, building or structure. Whilst educated in the structural and spatial language of architecture, my a new type of potter: the ceramic designer. ROWE practice combines this knowledge with an inquiry into the symbolic function and aesthetic activity of visual art,” he says. Rowe began making small, singular pieces and progressed into series of structures that make up a whole. -

Expo-Catalogue-EN.Pdf

FOREWORD Gaston Franco, MEP Host of the exhibition Member of the European Parliament President of the “Club du Bois” within the EP President of the Forest group within the EP Intergroup “Climate change, biodiversity and sustainable development” Wood is probably the most Wood as a material deserves to be worked by these environmentally friendly artists for our pleasure and our search for better ways material that nature has given to master the future. to man. It is made from CO2, It is for all these reasons, that I love wood and wood- captured from the atmosphere based products. by trees and stored in wood, Through this exhibition at the European Parliament, where the carbon will remain entitled Tackle climate change: use wood, to which locked for the entire lifespan I gladly lend my name, the artists seek to emphasise of the wood. and demonstrate the variety that wood in all its facets It is not only a magnificent ecological material, it is has to offer, whether it be as sculpture, craft, decora- also a technological material, perhaps even the most tion or message. innovative and the most extraordinary one at man’s It is my hope that this exhibition will convince disposal. Today, tomorrow, and for centuries to come, many that using wood and wood-based products now wood is and will continue to be this wonderful natural more than ever before will help us in achieving our material, at the same time common and mysterious, main policy goals which are to create a better, safer, beautiful and technical, visionary and renewable. -

Reading #2 Artistic Process and Training

Page | 1 Artistic Process and Training ART 100: Introduction to Art Reading #2 Artistic Process and Training This reading explores the artistic process and the art industry surrounding it: from individual artists turning ideas into works of art to collaborative creative projects, public art and the viewer. It covers the following topics: ● The Artistic Process ● The Role of Museums, galleries, and Critics ● The Individual Artist and Public Art ● Artistic Training The Artistic Process How many times have you looked at a work of art and wondered “how did they do that”? Some think of the artist as a solitary being, misunderstood by society, toiling away in the studio to create a masterpiece, and yes, there is something fantastic about a singular creative act becoming a work of art. The reality is that artists rely on a support network that includes family, friends, peers, industries, businesses, and, in essence, the whole society they live in. For example, an artist may need only a piece of paper and pencil to create an extraordinary drawing, but depends on a supplier in order to acquire those two simple tools. Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist (recto); Amorous Putti at Play; Head of a Bird (verso), 1530. Black and red chalk with pen and brown ink over stylus (recto); Pen and black and brown ink (verso), 27.9 × 39.4 cm (11 × 15 1/2 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Page | 2 Artistic Process and Training After the artwork is finished there are other support networks in place to help exhibit, market, move, store, and comment on it. -

The Great Indoors

The Great Indoors FRAMEWEB.COM/BOOKS CATALOGUE AUTUMN 2017 Contents 2 New Titles Goods 3 The Other Office 3 Grand Stand 6 8 Previously Announced Suppose (Un)Built JDS(A) Identity Architects Jo Nagasaka / Schemata Architects Studio O+A 13 Recent Titles Happening 2 Night Fever 5 Where They Create Japan Sound Materials Powershop 5 18 Portfolio Highlights Knowledge Matters Spaces for Innovation 3deluxe CMF design Onomatopoeia Goods 2 Grand Stand 5 Holistic Retail Design 22 Backlist 29 Index 30 Distributors 32 Contacts & Credits 2 NEW TITLES 3 GOODS 3 Interior Products from Sketch to Use Fifty iconic interior products from well-known designers and manufacturers from around the world are presented. The story of each is told over eight pages, from initial design sketch to its use in recently-designed interiors. Sketches and photographs show how the furniture and products are designed and made. Instead of just filling a book with new products, the Goods series analyses the design products featured from conceptual design sketch to realisation. This inspirational book also shows international reference projects where these products have been used successfully across all interior product ranges, from chairs to tables, from floor lamps to down lights, from kitchens to bathrooms. Frame editors select leading design producers and their associated designers. Producer, designer and editor decide together which product will be featured. Iconic design products are analysed and featured from conceptual design to realisation Category Product Design • This inspiring reference book is filled Authors Frame with the impelling stories of fifty Graphic Design Frame successful products. 392 pages 220 x 280 mm • Focuses on the material use and Hardcover manufacturing techniques of the £50 products and visualises these. -

Projects from Thelenarchitekten; Architekten Prof. Klaus Sill; Müller

13 L A T R O P PORTAL 13 PORTAL 13 INFORMATION FOR ARCHITECTS FROM HÖRMANN FEUER Fire Projects from thelenarchitekten; architekten prof. klaus sill; Müller Truniger Architekten and Studio Aldo Rossi PORTAL 13 INFORMATION FOR ARCHITECTS FROM HÖRMANN CONTENTS 3 EDITORIAL 4 / 5 / 6 / 7 THE FIRE-PROOF CITY How fire has changed the face of our cities Author: Daniel Leupold 8 / 9 / 10 / 11 FIRE EQUIPMENT HOUSE IN ROMMERSKIRCHEN RAL 3003 as far as the eye can see: for the volunteer fire brigade in Rommerskirchen in the Lower Rhine region, thelenarchitekten designed a monolithic new building in fire engine red. Design: thelenarchitekten, Düsseldorf 12 / 13 / 14 / 15 / 16 / 17 / 18 / 19 FIRE AND RESCUE STATION IN LÖHNE Messages behind glass characterise the facade of the station in Löhne, East Westphalia. Although situated directly on the highway, the building‘s interior offers employees a tranquil, high-quality atmosphere. Design: architekten prof. klaus sill, Hamburg 20 / 21 / 22 / 23 / 24 / 25 INTERVENTION CENTRE IN FRUTIGEN Swiss innovation and versatility: the intervention centre was once used as an assembly hall for the construction of the Lötschberg Tunnel. Today it serves as the operating base for both the tunnel‘s own fire brigade and the local fire department. Design: Müller & Truniger Architekten, Zurich 26 / 27 / 28 / 29 A HOTSPOT: THEATRE LA FENICE IN VENICE Thrice in flames: The famous theatre La Fenice in Venice has a fiery past. The building last burned in 1996 due to arson. It all started because of a damage claim of 7500 euros. Design (reconstruction): Studio Aldo Rossi, Milan 30 / 31 HÖRMANN CORPORATE NEWS 32 / 33 ARCHITECTURE AND ART Arne Quinze: Uchronia 34 / 35 PREVIEW / IMPRINT / HÖRMANN IN DIALOGUE Cover illustration: Arne Quinze: "Uchronia“ Photo: Arne Quinze EDITORIAL Martin J. -

Being out There: the Challenges and Possibilities of Public Art in Shanghai

Julie Chun Being Out There: The Challenges and Possibilities of Public Art in Shanghai “The predicament of public art emanates from problems of categories, of content, systems of reference, and conditions of events.” –Siah Armajani1 “Where there is no struggle, there is no strength.” (Permanently etched onto the tallest public mural in Asia, Busan, South Korea) –Hendrik Beikirch2 While the production and placement of art in public spaces is generally founded upon utopian ideals that seek to bridge art and the community, the realities of seeing such projects to completion are often riddled with contention. Public art often requires district, city, and state permits. Large national memorials must go through a series of public hearings before work can commence. Even while the installation of the work is in middle of production or after full completion, public opinion can further alter its course. History reveals the heated debate provoked by Maya Lin’s abstract design for the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial (completed in 1982) in Washington, D.C. which was placated by the subsequent placement of the figurative bronze sculptures The Three Servicemen (1984), by Frederick Hart, and the Vietnam Women’s Memorial (1993), by Glenna Goodacre. Moreover, we need only be reminded of Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc (1981), sited on Foley Federal Plaza in New York City, which came under attack by the public for almost a decade and in 1989 was eventually removed in response to this outcry. If these cases represent complex challenges in a democratic society like the United States, are obstacles inherent to public art more or less difficult to negotiate in a single-party state like the People’s Republic of China? The notion of supporting public art in a collective society should hardly seem paradoxical. -

Short History for Dubai 2017 Van Der Koelen 2017-03-02

PRESS RELEASE – ART DUBAI 2017 SHORT HISTORY OF THE GALLERY & ARTISTS The first gallery of Dorothea van der Koelen was founded in 1979 in Mainz under the name ›Galerie Dorothea van der Koelen‹. 1986 she opened a second exhibition space in the industrial area of the city of Mainz, called ›Dammweg Art Hall‹, followed by a third gallery in Venice, called ›La Galleria‹, opened parallel to the Venice Art Biennale in 2001. Beside the 3 galleries Dr. Dorothea van der Koelen founded, together with her brother Martin, in 1995 a publishing house for art books called ›Chorus-Verlag‹ and set up in 2003 the ›van der Koelen Foundation for Art and Science (on art)‹. In 2014 she was able to open the ›CADORO – Centre for Arts and Science‹ in Mainz, that obtains on 2.000 sqm production with an artist studio, reception with researches on art and a library with more than 35.000 books on (mostly) contemporary art, and distribution with the gallery work. Dorothea van der Koelen is working with about 20 – 30 international artists from 15 different countries. Beside the exhibitions in her own galleries she curated world wide exhibitions for museums and institutions. During the past 38 years all in all she was involved in about 550 - 600 shows in 28 countries. Beside publishing lectures and texts in more than 150 catalogues and books on contemporary art, the art historian Dr. Dorothea van der Koelen is specialized in art-in-architecture-projects and sculptures in public space and now is able to look back to more than 30 realized projects. -

N E W S B R I E F Denmark October, 2011

nordic 5 arts n e w s b r i e f www.nordic5arts.com Denmark October, 2011 Finland fall membership meeting Saturday, October 22, 10 AM - 12:30 PM Iceland On the Agenda Current and future exhibitions Program Maj-Britt Hilstrom: Drawing on the iPad Norway Marc Ellen Hamel: Norse Runes Hosted by Maj-Britt Hilstrom, 8665 Don Carol Dr., El Cerrito, CA 94530 Sweden unveiling of kati casida’s sculpture “JONSOK” “The overlaying of circles symbolizes the strong bonds that connect generations of Norwegian immigrants to their roots and to their family members who stayed behind. The flames repre- sent energy and search for the new as they dissolve into the vast emptiness of the sky.” - Kati Casida congratulations, kati! Casida, whose great grandparents came from the “Jonsok” is placed in a spectacular Luster Municipality in Sogn, Norway, paid a visit there location at the head of the longest in the early 1980’s on Midsummer’s Day (Jonsok.*) navigable fjord in the world - Sognef- She made a small model of a bonfire which was ex- jorden. The artist Magne Vangsnes was hibited and it was at that time that the idea emerged a driving force behind the commission, to produce a sculpture the size of a real bonfire. which became a reality with private Source: Sogn News, March 13, 2011 and public funding. The unveiling was * The summer solstice is celebrated by numerous countries and differs accord- attended by 300 people, including the ing to country and culture. Midsummer’s Day is also known as St. John’s Day. -

Smaller Fairs Mean Great Art, Closer to Home

Smaller Fairs Mean Great Art, Closer to Home nytimes.com/2020/03/14/arts/dallas-art-fair-art-brussels.html Ted March 14, Loos 2020 1/6 2/6 To many participants, the international art fair phenomenon has become a traveling circus of sorts — if it’s Thursday, this must be Art Basel Miami Beach. Or could it be Frieze London? Wake me when it’s time for the next TEFAF. But in the age of the coronavirus, with such events being canceled or postponed — along with many other cultural happenings — the same participants who used to complain about the rigorous schedule may find themselves wistful for the days of regular programming. Two fairs that were scheduled for this spring but delayed because of the pandemic illustrate why such events can thrive: There are serious collectors everywhere, particularly for contemporary art, and they do not always want to get on a plane to look at a work they may want to buy. The majority of art fairs are for the people who live in the host city. Catering to the local base of collectors is something of a specialty for the Dallas Art Fair, a gathering of about 94 dealers that was scheduled for April and has moved to Oct. 2 to 4, and Art Brussels, which was also scheduled to be a gathering of nearly 160 dealers in April and has even more optimistically chosen June 26 to 28 as its new slot. In some ways, the fairs are as different as their host cities. The Dallas fair, established in 2009, is newer and brasher and is held in the Fashion Industry Gallery of the city’s arts district. -

PRESS KIT Forging New Ties with the City

PRESS KIT Forging new ties with the city NOVEMBER 2019 A world-class exhibition The complex complex IN 2024 ‘‘Our goal in renovating Paris Expo Porte de Versailles is to keep Paris at the forefront of the international business tourism market. We are reinventing the site for users, organisers, exhibitors, visitors and our neighbours – transforming it into a flagship 21st-century complex that is more sustainable and open: an elegant, vibrant and cutting- edge place. This ambitious ten-year project was launched in May 2015, and will deliver a venue that is compliant with the strictest international standards, a model of sustainable development and a destination offering both leisure activities and a major business hub. And while all this is going on, we are open for business. Welcome to Paris Expo Porte de Versailles, the permanent universal exposition!’’ PABLO NAKHLÉ CERRUTI, CEO of Viparis PHASE 1 PHASE 2 PHASE 3 Renovation of Pavilion 7 and Demolition of Pavilions 6 and 8 Restructuring of Pavilions 2 and 3 creation of Paris Convention Centre as well as car park C Development of the exterior spaces An improved visitor experience: Construction of the Gate B plaza with to the west of Pavilion 7 reconfiguration of the central walkway a large-scale sculpture by Arne Quinze and the Gate A plaza Construction of a new car park 6 An enhanced north facade Creation of Pavilion 6 for Pavilion 1 with its illuminated canopy Reorganisation of the D4 Two new hotels: logistical platform Mama Shelter and Novotel THE PROJECT An ambitious An ambitious architectural architectural challenge challenge aris Expo Porte de Versailles’s ren- The facades of Pavilions 2 and 3 refl ect an Bullit Studio Bullit P ovation project was inspired by its interplay of refl ective and matte materials, © origins as a fairground – a distinc- volumes and voids, as well as vertical, hori- tive heritage. -

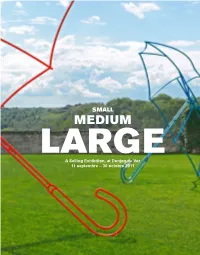

Thomas LEROOY Né En 1981 NOT ENOUGH BRAIN to SURVIVE

BALKENHOL Stephan 74 Ouvert tous les jours 14 – 18 heures BRAJKOVIC Sebastian 80 Open daily 2 – 6 PM BREUNING Olaf 10, 16 COMBAS Robert 26 CRAIG-MARTIN Michaël 62 DONJON DE VEZ DINE Jim 36, 60 60117 VEZ – France FLEURY Patrick 38 +33 3 44 88 55 18 FIRMAN Daniel 94 www.donjondevez.com GRASSO Laurent 56 HEIN Jeppe 52 HOLLER Carsten 24 Œuvres a vendre KCHO 12 All works are available for sale LALANNE François-Xavier 44 Prix sur demande LEGER Fernand (d’après) 66 Prices upon request LEROOY Thomas 68 MATELLI Tony 30, 90 MORELLET François 86 OP DE BEECK Hans 82 OPIE Julian 70 OULAB Yazid 78 QUINZE Arne 8, 20, 96 REINOSO Pablo 34 TURK Gavin 6 VASCONCELOS Joana 48 VENET Bernar 40 SMALL MEDIUM LARGE A Selling Exhibition, at Donjon de Vez 11 septembre – 30 octobre 2011 Contacts Susanne van Hagen +33 1 43 06 28 45 Emmanuelle Dybich +33 1 43 06 45 94 [email protected] Guillaume Mallecot +33 1 42 99 20 33 en partenariat avec Artcurial [email protected] BALKENHOL Stephan 74 Ouvert tous les jours 14 – 18 heures BRAJKOVIC Sebastian 80 Open daily 2 – 6 PM BREUNING Olaf 10, 16 COMBAS Robert 26 CRAIG-MARTIN Michaël 62 DONJON DE VEZ DINE Jim 36, 60 60117 VEZ – France FLEURY Patrick 38 +33 3 44 88 55 18 FIRMAN Daniel 94 www.donjondevez.com GRASSO Laurent 56 HEIN Jeppe 52 HOLLER Carsten 24 Œuvres a vendre KCHO 12 All works are available for sale LALANNE François-Xavier 44 Prix sur demande LEGER Fernand (d’après) 66 Prices upon request LEROOY Thomas 68 MATELLI Tony 30, 90 MORELLET François 86 SMALL OP DE BEECK Hans 82 OPIE Julian 70 OULAB Yazid 78 QUINZE