Informal Voting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2020 Facts and Trends 2019/20 2

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 FACTS AND TRENDS 2019/20 2 Import Coal Market at a Glance 2017 2018 2019 World Hard Coal Production Mill. t 6,852 7,064 7,257 World Hard Coal Trade Mill. t 1,267 1,324 1,336 of which seaborne hard coal trade Mill. t 1,157 1,208 1,221 of which internal hard coal trade Mill. t 110 116 115 Hard Coal Coke Production Mill. t 633 646 682 Hard Coal Coke World Trade Mill. t 26 28 26 European Union (28) Hard Coal Production Mill. TCE 81 76 67 Hard Coal Imports (incl. internal trade) Mill. t 172 166 134 Hard Coal Coke Imports Mill. t 9.1 9.0 9.5 Germany Hard Coal Use Mill. TCE 50.0 48.7 38.7 Hard Coal Volume Mill. TCE 51.6 47.1 37.9 of which import coal use Mill. TCE 47.9 44.4 37.9 of which domestic hard coal production Mill. TCE 3.7 2.7 0.0 Imports of Hard Coal and Hard Coal Coke Mill. t 51.4 47.0 42.2 of which steam coal 1) Mill. t 36.3 32.5 29.2 of which coking coal Mill. t 12.9 12.4 11.2 of which hard coal coke Mill. t 2.3 2.1 1.9 Prices Steam Coal Marker Price CIF NWE US$/TCE 98 108 72 Border-crossing Price Steam Coal €/TCE 92 95 79 CO2 emission rights (EEX EUA settlement price) EUR/EUA 5.83 15.82 24.84 Exchange rate (US$1 = €....) EUR/US$ 0.89 0.85 0.90 1) Including anthracite and briquettes Quelle: ??? 3 AN INTRODUCTORY WORD In 2020, it will be decided to end coal-fired power generation. -

Proposed Redistribution of Victoria Into Electoral Divisions: April 2017

Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions APRIL 2018 Report of the Redistribution Committee for Victoria Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 Feedback and enquiries Feedback on this report is welcome and should be directed to the contact officer. Contact officer National Redistributions Manager Roll Management and Community Engagement Branch Australian Electoral Commission 50 Marcus Clarke Street Canberra ACT 2600 Locked Bag 4007 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: 02 6271 4411 Fax: 02 6215 9999 Email: [email protected] AEC website www.aec.gov.au Accessible services Visit the AEC website for telephone interpreter services in other languages. Readers who are deaf or have a hearing or speech impairment can contact the AEC through the National Relay Service (NRS): – TTY users phone 133 677 and ask for 13 23 26 – Speak and Listen users phone 1300 555 727 and ask for 13 23 26 – Internet relay users connect to the NRS and ask for 13 23 26 ISBN: 978-1-921427-58-9 © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 © Victoria 2018 The report should be cited as Redistribution Committee for Victoria, Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions. 18_0990 The Redistribution Committee for Victoria (the Redistribution Committee) has undertaken a proposed redistribution of Victoria. In developing the redistribution proposal, the Redistribution Committee has satisfied itself that the proposed electoral divisions meet the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). The Redistribution Committee commends its redistribution -

Comment on Suggestion 54

Comment on suggestion 54 Victorian Labor Party (Victorian Branch) 10 pages Victorian secretariat Phone (03) 9285 7197 Fax (02) 6293 7664 Email [email protected] From: Justin Barbour To: FedRedistribution - VIC Cc: Subject: Victorian Labor"s Comment on Suggestions Date: Friday, 1 December 2017 3:07:59 PM Attachments: Victorian Labor’s Suggestions Narrative + Transfers 301117.pdf ATT00001.htm Dear Redistribution Committee for Victoria Please find attached Comments on Suggestions from the Australian Labor Party (Victorian Branch) in relation to the 2017-18 Federal redistribution in Victoria. Grateful if this email and submission could please be acknowledged as received. Regards, Justin Justin Barbour Victorian Labor Party (Victorian Branch) This email message is intended only for the addressee(s) and contains information that may be confidential and/or copyright. If you are not the intended recipient please notify the sender by reply email and immediately delete this email. Use, disclosure or reproduction of this email by anyone other than the intended recipient(s) is strictly prohibited. No representation is made that this email or any attachments are free of viruses. Virus scanning is recommended and is the responsibility of the recipient. OVERVIEW When formulating our suggestions to the Redistribution Committee the Australian Labor Party (Victorian Branch) (ALP) was mindful of the fact that this Redistribution will apply to the next Parliament. The quarterly Demographic Statistics released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in September confirmed that Victoria’s annual population growth continues to be 50% greater than the Australian average. As the Committee has concluded Victoria’s growth rate will soon gain the State with an extra Division. -

Delivering the Future

Delivering the Future Private Irrigation Infrastructure Operators Program in NSW (PIIOP) Round Two Final Report October 2019 Murray Irrigation Limited (ABN 23 067 197 933) is a Company limited by shares, incorporated and domiciled in Australia. Its registered office and principal place of business is: 443 Charlotte Street PO BOX 528 Deniliquin NSW 2710 Telephone: 1300 138 265 Facsimile: (03) 5898 3301 www.murrayirrigation.com.au [email protected] Board of Directors The current directors of the Company are: P. Snowden C. Filson W. Van Beek R. Gleeson N. Baxter S. Fawns P. Largier D. Marples Chief Executive Officer Michael Renehan (2014 - June 2019) Philip Endley (Current since August 2019) Design Thirst Creative Photography Sarah Enticknap Peter Clarke ISBN 978-0-9923511-6-8 Table of Contents 1 Chief Executive Officer’s Report ........................................................................................................................... 4 2 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 5 3 Executive GM Major Engineering Projects' Report ............................................................................................... 7 BENEFITS OF MODERNISATION .......................................................................................................................... 9 4 Historical Insights ............................................................................................................................................... -

Victorian and ACT Electoral Boundary Redistribution

Barton Deakin Brief: Victorian and ACT Electoral Boundary Redistribution 9 April 2018 Last week, the Australian Electoral Commission (‘AEC’) announced substantial redistributions for the Electorate Divisions in Victoria and the ACT. The redistribution creates a third Federal seat in the ACT and an additional seat in Victoria. These new seats are accompanied by substantial boundary changes in Victoria and the ACT. ABC electoral analyst Antony Green has predicted that the redistribution would notionally give the Australian Labor Party an additional three seats in the next election – the Divisions of Dunkley, Fraser, and Bean – while the seat of Corangamite would become one of the most marginal seats in the country. The proposed changes will now be subject to a consultation period where objections to the changes may be submitted to the AEC. The objection period closes at 6pm May 4 in both the ACT and Victoria. A proposed redistribution for South Australia will be announced on April 13. This Barton Deakin Brief will summarize the key electoral boundary changes in the ACT and Victoria. New Seats The Redistribution Committee has proposed that four of Victoria’s electoral divisions be renamed. Additionally, two new seats are to be created in Victoria and the ACT New Seats Proposed for Victoria and ACT DIVISION OF BEAN (ACT) New seat encompassing much of the former Division of Canberra. The seat will be named after World War I war correspondent Charles Edwin Woodrow Green (1879-1968) DIVISION OF FRASER (VIC) New seat named after former Liberal Party Prime Minister John Malcolm Fraser AC CH GCL (1930-2015), to be located in Melbourne’s western suburbs. -

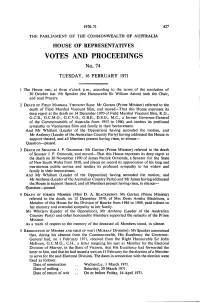

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1970-71 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 74 TUESDAY, 16 FEBRUARY 1971 1 The House met, at three o'clock p.m., according to the terms of the resolution of 30 October last. Mr Speaker (the Honourable Sir William Aston) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 DEATH OF FIELD MARSHAL VISCOUNT SLIM: Mr Gorton (Prime Minister) referred to the death of Field Marshal Viscount Slim, and moved-That this House expresses its deep regret at the death on 14 December 1970 of Field Marshal Viscount Slim, K.G., G.C.B., G.C.M.G., G.C.V.O., G.B.E., D.S.O., M.C., a former Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia from 1953 to 1960, and tenders its profound sympathy to Viscountess Slim and family in their bereavement. And Mr Whitlam (Leader of the Opposition) having seconded the motion, and Mr Anthony (Leader of the Australian Country Party) having addressed the House in support thereof, and all Members present having risen, in silence- Question-passed. 3 DEATH OF SENATOR J. P. ORMONDE: Mr Gorton (Prime Minister) referred to the death of Senator J. P. Ormonde, and moved-That this House expresses its deep regret at the death on 30 November 1970 of James Patrick Ormonde, a Senator for the State of New South Wales from 1958, and places on record its appreciation of his long and meritorious public service and tenders its profound sympathy to his widow and family in their bereavement. And Mr Whitlam (Leader of the Opposition) having seconded the motion, and Mr Anthony (Leader of the Australian Country Party) and Mr James having addressed the House in support thereof, and all Members present having risen, in silence- Question-passed. -

A History of the Electrical Trades Union in Western Australia and Its Place in the Labour Movement from 1905 to 1979

A History of the Electrical Trades Union in Western Australia and Its Place in the Labour Movement from 1905 to 1979 Linda Jane McLaughlan BA (Hons) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2013 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. Signed: ____________________________________ ABSTRACT This thesis is the first scholarly study of the organisation representing electrical trades workers in Western Australia, from its inception in 1905 to 1979. It examines how a small craft union was created, how it won and maintained its independence and fostered the singular skill base of its members, and how it developed and strengthened its power. The thesis argues that the union fought to create and maintain a separate trade union identity based on specific trade skills within the electrical trades in the face of opposition from already-established metal trade unions. In 1905 the Metropolitan Electrical Trades Union (METU) was established. This was the first union to represent electrical workers in Western Australia. In 1914 the METU amalgamated with the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (ASE) / Amalgamated Engineering Union (AEU). Many electrical workers were unhappy with this amalgamation and in 1926, with the assistance of the national body of the Electrical Trades Union of Australia, a union known as the Electrical Trades Union of Australia (Western Australian Branch) (ETUWA) was established. From 1927 until 1949 the ETUWA was embroiled in a long bitter struggle to regain its independence. -

Richmond-Tweed Family History Society

Richmond-Tweed Family History Society Inc - Catalogue Call No Title Author Nv-1Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Aston Nv-2Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Ballarat Nn-15Y 1984 Electoral roll : Division of Banks Nn-14Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Barton Nt-1Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Bass Nv-3Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Batman Nv-4Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Bendigo Nn-12Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Berowra Nn-11Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Blaxland Ns-4Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Boothby Nq-1Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Bowman Nt-2Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Braddon Nn-16Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Bradfield Nw-1Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Brand Nq-2Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Brisbane Nv-5Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Bruce Nv-6Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Burke Nv-7Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Calwell Nw-2Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Canning Nq-3Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Capricornia Nv-8Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Casey Nn-17Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Charlton Nn-23Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Chifley Nv-9Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Chisholm 06 October 2012 Page 1 of 167 Call No Title Author Nn-22Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Cook Nv-10Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Corangamite Nv-11Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Corio Nw-3Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Cowan Nn-21Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Cowper Nn-20Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Cunningham -

Answers to Questions on Notice Budget Estimates 2014-15

Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE BUDGET ESTIMATES 2014-15 Finance Portfolio Department/Agency: All Outcome/Program: General Topic: Staffing profile Senator: Ludwig Question reference number: F210 Type of question: Written Date set by the committee for the return of answer: Friday, 11 July 2014 Number of pages: 16 Question: 1. What is the current staffing profile of the department/agency? 2. Provide a list of staffing numbers, broken down by classification level, division, home base location (including town/city and state). Answer: As at 31 May 2014: Department/ Response Agency Finance 1. The staffing profile for the Department was 1430 ongoing, 11 non-going and 331 casual employees. 2. Refer to Attachment A. Australian 1. As at 31 May 2014: Electoral Commission Full time staff Part time staff Casual staff Total 680 176 1780 2636 This table excludes contractors and temporary election/by-election staff. 2. Refer Attachment B. ComSuper 1 - 2. All ComSuper staff are located in Canberra, ACT. ComSuper’s staffing profile, by classification and branch, is at Attachment C. Commonwealth 1. There were 75 staff employed being full-time 66, part time 7, and casual 2. This Superannuation represented a Full Time Equivalent of 71.77 staff. Corporation 2. CSC does not use classification levels for its employees. The staff divisions are as follows: • CEO Office 2; • Board Services 2; 1 Department/ Response Agency • Chief Investment Officer 17; • Member & Employer Services 14.87; • General Counsel 3; • Finance & Risk 16.23; • Operations 16.67. Staff are located as follows: • Sydney, NSW – 20; • Canberra, ACT – 53; • Brisbane, QLD – 1; • Melbourne, VIC – 1. -

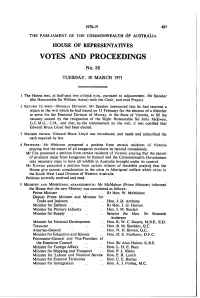

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1970-71 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 88 TUESDAY, 30 MARCH 1971 1 The House met, at half-past two o'clock p.m., pursuant to adjournmeit. Mr Speaker (the Honourable Sir William Aston) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 RETURN TO WRIT-MURRAY DIVISION: Mr Speaker announced that he had received a return to the writ which he had issued on 15 February for the election of a Member to serve for the Electoral Division of Murray, in the State of Victoria, to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of the Right Honourable Sir John McEwen, G.C.M.G., C.H., and that, by the endorsement on the writ, it was certified that Edward Bruce Lloyd had been elected. 3 MEMBER SWORN: Edward Bruce Lloyd was introduced, and made ahd subscribed the oath required by law. 4 PETITIONS: Mr Whittorn presented a petition from certain residents of Victoria praying that the export of all kangaroo products be banned immediately. Mr Fox presented a petition from certain residents of Victoria praying that the export of products made from kangaroos be banned and the Cdmmofiwealth Goveinment take necessary steps to have all wildlife in Australia brought under its control. Mr Kirwan presented a petition from certain citizens of Austidlia pra'ing that the House give earnest consideration to the crisis in Aboriginal Welfare which exists in the South West Land Division of Western Australia. Petitions severally received and read. 5 MINISTRY AND MINISTERIAL ARRANGEMENTS: Mr McMahon (Prime Minister) informed the House that the new Ministry was constituted as follows: Prime Minister . -

The NSW Redistribution 2005-06

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library RESEARCH BRIEF Information analysis and advice for the Parliament 1 February 2007, no. 8, 2006–07, ISSN 1832-2883 'Save Country Seats': the NSW redistribution 2005–06 The recently-completed redistribution for the NSW House of Representatives seats was unusually controversial. There was concern in rural areas over the loss of a country seat— which was also a ‘Federation’ seat—and dismay over the apparent pushing–aside of the ‘community of interest’ principle by the Redistribution Committee. The controversy revealed a lack of community understanding of the redistribution process and an apparent reluctance by the Australian Electoral Commission to engage fully with the public. This paper discusses the controversy, analyses the changes to the redistribution that were made as a result the controversy, and poses the question of whether the redistribution arrangements need alteration. Scott Bennett Politics and Public Administration Section Contents Executive summary ................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................ 2 When are redistributions held? ........................................... 2 Who conducts a redistribution?........................................... 3 Public input? ........................................................ 4 What are the aims of a redistribution? ...................................... 5 Equality ......................................................... 5 Enrolment -

MG Unit Trust Product Disclosure Statement

MG Unit Trust Product Disclosure Statement Issued by MG Responsible Entity Limited ACN 601 538 970 AFSL 472856 THIS IS AN IMPORTANT DOCUMENT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. IF YOU ARE IN ANY DOUBT ABOUT HOW TO DEAL WITH THIS DOCUMENT, YOU SHOULD For personal use only CONTACT YOUR BROKER, FINANCIAL ADVISER OR LEGAL ADVISER IMMEDIATELY. Sole Lead Manager Important Notes Offer Important Information for New Zealand investors The Offer contained in this Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) This offer to New Zealand investors is a regulated offer is an invitation to acquire fully paid units in the MG Unit Trust made under Australian and New Zealand law. In Australia, (ARSN 606 103 637) (MG Unit Trust) (Units). This PDS is this is Chapter 8 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and issued by MG Responsible Entity Limited (ACN 601 538 970, Regulations. In New Zealand, this is Part 5 of the Securities AFSL 472856) as responsible entity of the MG Unit Trust Act 1978 and the Securities (Mutual Recognition of Securities (Responsible Entity). The Responsible Entity is a wholly-owned Offerings – Australia) Regulations 2008. subsidiary of Murray Goulburn Co-operative Co. Limited (ACN This offer and the content of the offer document are principally 004 277 089) (Murray Goulburn). governed by Australian rather than New Zealand law. In the main, This PDS does not contain an offer of shares or other the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and Regulations (Australia) set securities in Murray Goulburn. While the performance of the out how the offer must be made. MG Unit Trust is linked to the performance of Murray Goulburn, There are differences in how securities are regulated under Murray Goulburn is not the issuer of the PDS nor of the Units.