Tsp2012humphries.Pdf (978.5Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Spring/Summer Ca T Alogue

2017 SPRING/SUMMER CATALOGUE LOOK WHO’S WATCHING Untold Stories of the ER Gary R. Benz Marielle Zuccarelli President and Chief Operating Officer Chief Executive Officer [email protected] [email protected] +1-818-728-7649 +1-818-728-7697 GRB ENTERTAINMENT GRB ENTERTAINMENT Michael Lolato Liz Levenson Senior Vice President, Vice President, International International Distribution Acquisitions and Sales [email protected] [email protected] +1-818-728-7614 +1-818-728-7637 ABOUT US Welcome to GRB Entertainment. We pride ourselves on being one of the most dynamic, diverse, and robust production and distribution companies in the world. Providing content to global broadcasters for nearly 30 years, GRB Entertainment is synonymous with engaging characters, meaningful stakes, and storytelling that Melanie Torres Melissa Weinstein matters. The company has paved the way in the development and distribution Director, International Sales Manager, International Sales of boundary-pushing, provocative programming, including the Emmy-award [email protected] and Marketing +1-818-728-7651 [email protected] winning series Intervention for A&E. +1-818-728-4140 GRB’s international team is recognized as one of the premiere distributors of quality programming, with timely servicing and unmatched professionalism, and we are thrilled to have been selected as part of Realscreen Magazine’s Global 100 list of most influential distribution companies in the world. From top rated scripted programs, to riveting unscripted and factual series, to powerful documentaries, Mike Greenberg GRB Entertainment’s catalogue is diverse and compelling, with content that has Traffic Director [email protected] true global appeal. We look forward to working with you. -

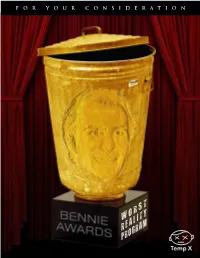

Worst Reality Program PROGRAM TITLE LOGLINE NETWORK the Vexcon Pest Removal Team Helps to Rid Clients of Billy the Exterminator A&E Their Extreme Pest Cases

FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION WORST REALITY PROGRAM PROGRAM TITLE LOGLINE NETWORK The Vexcon pest removal team helps to rid clients of Billy the Exterminator A&E their extreme pest cases. Performance series featuring Criss Angel, a master Criss Angel: Mindfreak illusionist known for his spontaneous street A&E performances and public shows. Reality series which focuses on bounty hunter Duane Dog the Bounty Hunter "Dog" Chapman, his professional life as well as the A&E home life he shares with his wife and their 12 children. A docusoap following the family life of Gene Simmons, Gene Simmons Family Jewels which include his longtime girlfriend, Shannon Tweed, a A&E former Playmate of the Year, and their two children. Reality show following rock star Dee Snider along with Growing Up Twisted A&E his wife and three children. Reality show that follows individuals whose lives have Hoarders A&E been affected by their need to hoard things. Reality series in which the friends and relatives of an individual dealing with serious problems or addictions Intervention come together to set up an intervention for the person in A&E the hopes of getting his or her life back on track. Reality show that follows actress Kirstie Alley as she Kirstie Alley's Big Life struggles with weight loss and raises her two daughters A&E as a single mom. Documentary relaity series that follows a Manhattan- Manhunters: Fugitive Task Force based federal task that tracks down fugitives in the Tri- A&E state area. Individuals with severe anxiety, compulsions, panic Obsessed attacks and phobias are given the chance to work with a A&E therapist in order to help work through their disorder. -

Admitted Pro Hac Vice) JONES DAY 222 East 41St Street New York, NY 10017 Tel: (212) 326-3939 Fax: (212) 755-7306 - and - Craig A

15-11989-mew Doc 1692 Filed 03/23/16 Entered 03/23/16 20:08:56 Main Document Pg 1 of 127 Richard L. Wynne, Esq. Bennett L. Spiegel, Esq. Lori Sinanyan, Esq. (admitted pro hac vice) JONES DAY 222 East 41st Street New York, NY 10017 Tel: (212) 326-3939 Fax: (212) 755-7306 - and - Craig A. Wolfe, Esq. Malani J. Cademartori, Esq. Blanka K. Wolfe, Esq. SHEPPARD MULLIN RICHTER & HAMPTON LLP 30 Rockefeller Plaza New York, NY 10112 Tel: (212) 653-8700 Fax: (212) 653-8701 Co-Counsel to the Debtors and Debtors in Possession UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK In re: Chapter 11 RELATIVITY FASHION, LLC, et al.,1 Case No. 15-11989 (MEW) Debtors. (Jointly Administered) NOTICE OF FILING OF AMENDED AND RESTATED EXHIBIT E TO THE PLAN PROPONENTS' FOURTH AMENDED AND RESTATED PLAN OF REORGANIZATION PURSUANT TO CHAPTER 11 OF THE BANKRUPTCY CODE 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases are as set forth on: see page (i). NAI-1500922712v1 15-11989-mew Doc 1692 Filed 03/23/16 Entered 03/23/16 20:08:56 Main Document Pg 2 of 127 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtor's federal tax identification number, are: Relativity Fashion, LLC (4571); Relativity Holdings LLC (7052); Relativity Media, LLC (0844); Relativity REAL, LLC (1653); RILL Distribution Domestic, LLC (6528); RILL Distribution International, LLC (6749); REMOLD Financing, LLC (9114); 21 & Over Productions, LLC (7796); 3 Days to Kill Productions, LLC (5747); A Perfect Getaway PER, LLC (9252); A Perfect Getaway, LLC (3939); Armored Car -

2017 Autumn/Winter Ca T Alogue

2017 AUTUMN/WINTER CATALOGUE Crunch Time Untold Stories of the ER Gary R. Benz Marielle Zuccarelli President and Chief Operating Officer Chief Executive Officer [email protected] [email protected] +1-818-728-7649 +1-818-728-7697 GRB ENTERTAINMENT GRB ENTERTAINMENT Michael Lolato Liz Levenson Senior Vice President, Vice President, International International Distribution Acquisitions and Sales [email protected] [email protected] +1-818-728-7614 +1-818-728-7637 ABOUT US Welcome to GRB Entertainment. We pride ourselves on being one of the most dynamic, diverse, and robust production and distribution companies in the world. Providing content to global broadcasters for nearly 30 years, GRB Entertainment is synonymous with engaging characters, meaningful stakes, and storytelling that Melanie Torres Melissa Weinstein matters. The company has paved the way in the development and distribution Director, International Sales Manager, International Sales [email protected] and Marketing of boundary-pushing, provocative programming, including the Emmy-award +1-818-728-7651 [email protected] winning series Intervention for A&E. +1-818-728-4140 GRB’s international team is recognized as one of the premiere distributors of quality programming, with timely servicing and unmatched professionalism, and we are thrilled to have been selected as part of Realscreen Magazine’s Global 100 list of most influential distribution companies in the world. From top rated scripted Mike Greenberg programs, to riveting unscripted and factual series, to powerful documentaries, Jeffrey Park Traffic Director Vice President, GRB Entertainment’s catalogue is diverse and compelling, with content that has [email protected] Business & Legal Affairs true global appeal. -

TAL Direct: Sub-Index S912c Index for ASIC

TAL.500.002.0503 TAL Direct: Sub-Index s912C Index for ASIC Appendix B: Reference to xv: A list of television programs during which TAL’s InsuranceLine Funeral Plan advertisements were aired. 1 90802531/v1 TAL.500.002.0504 TAL Direct: Sub-Index s912C Index for ASIC Section 1_xv List of TV programs FIFA Futbol Mundial 21 Jump Street 7Mate Movie: Charge Of The #NOWPLAYINGV 24 Hour Party Paramedics Light Brigade (M-v) $#*! My Dad Says 24 HOURS AFTER: ASTEROID 7Mate Movie: Duel At Diablo (PG-v a) 10 BIGGEST TRACKS RIGHT NOW IMPACT 7Mate Movie: Red Dawn (M-v l) 10 CELEBRITY REHABS EXPOSED 24 hours of le mans 7Mate Movie: The Mechanic (M- 10 HOTTEST TRACKS RIGHT NOW 24 Hours To Kill v a l) 10 Things You Need to Know 25 Most Memorable Swimsuit Mom 7Mate Movie: Touching The Void 10 Ways To Improve The Value O 25 Most Sensational Holly Melt -CC- (M-l) 10 Years Younger 28 Days in Rehab 7Mate Movie: Two For The 10 Years Younger In 10 Days Money -CC- (M-l s) 30 Minute Menu 10 Years Younger UK 7Mate Movie: Von Richthofen 30 Most Outrageous Feuds 10.5 Apocalypse And Brown (PG-v l) 3000 Miles To Graceland 100 Greatest Discoveries 7th Heaven 30M Series/Special 1000 WAYS TO DIE 7Two Afternoon Movie: 3rd Rock from the Sun 1066 WHEN THREE TRIBES WENT 7Two Afternoon Movie: Living F 3S at 3 TO 7Two Afternoon Movie: 4 FOR TEXAS 1066: The Year that Changed th Submarin 112 Emergency 4 INGREDIENTS 7TWO Classic Movie 12 Disney Tv Movies 40 Smokin On Set Hookups 7Two Late Arvo Movie: Columbo: 1421 THE YEAR CHINA 48 Hour Film Project Swan Song (PG) DISCOVERED 48 -

Alaskan Sn01 Everyday!

i; Several f; -water || . quality I; meetings 1! \ are coining up Si See page 9 VOLUME 44, NUMBER 38 WEEK OF NOVEMBER 11 - 17,2005 f- *;•: .'V F^&feg LAVISH 8 FABULOUS - OVER 75 ITEMS - ALL YOU CAN EAT IMs HoBday Feast s QManfeed te> Sagger the SbV.est .1 • Acx&.s' ; Serving Thursday, November 24th - Noon to Close • Reservations Requested • 395-2300 ALASKAN SN01 Not good with any other promotion or discount. Open Mon - Sat @11 am Sunday 9:00am This promotion good through November 23 and subject to change at any time. AU yOU CAN EAT EVERYDAY!! 2330 Palm Ridge Rd. Sanibei Island No Holidays. Must present ad. 37 ii&ms @n the '"Cwslder the Kids" EVERYDAY! AM spesIaSs stAJect to awaiteiaisff« vvith Frdrtch Fries & corn on the cob Master Card, Visa, Discover Credit Cards Accepted Sunday 9:00-1 2:00 noon November 1t -17, 2005 ISLANDER Short te No te .200/0 .50%' 4 APY 4 APY 7-Month 13-Month For more Information, visit coionialbank.com or call (877) 502-2265. COLONIAL BANK. °w°wzv.colonialbank.com " IVEember FDIC . *Annual Percentage Yield (APY) as of this printing, and subject to change without notice. The APY reflects the total amount of interest earned based Hailey Magenheim from Cincinnati, Ohio found an on the interest rate and frequency of compounding for a 365-day period. Minimum opening deposit $500 (Nevada $1,000, Texas $2,500). This offer cannot be used in conjunction with any other advertised special. Substantial penalty for early withdrawal. Not available to financial institutions. -

1- United States Bankruptcy Court Southern District Of

15-12065-mew Doc 5 Filed 09/25/15 Entered 09/25/15 07:46:12 Main Document Pg 1 of 345 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK In re: Chapter 11 RELATIVITY FASHION, LLC, et al.,1 Case No. 15-11989 (MEW) Debtors. (Jointly Administered) GLOBAL NOTES REGARDING THE DEBTORS’ SCHEDULES OF ASSETS AND LIABILITIES AND STATEMENTS OF FINANCIAL AFFAIRS Relativity Fashion LLC, Relativity Holdings LLC, Relativity Media LLC (“RML”) and their affiliated debtors and debtors in possession (collectively, the “Debtors”), are filing their respective Schedules of Assets and Liabilities (each, a “Schedule” and, collectively, the “Schedules”) and Statements of Financial Affairs (each, a “SOFA” and, collectively, the “Statements”) pursuant to section 521 of title 11 of the United States Code (the “Bankruptcy Code”) and Rule 1007 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedures (the “Bankruptcy Rules”). The Debtors’ management prepared the Schedules and Statements with the assistance of their advisors and other professionals. The Schedules and Statements are unaudited. The Debtors’ management and advisors have made reasonable efforts to ensure that they are as accurate and complete as possible under the circumstances based on information that was available to them at the time of preparation; however, subsequent information or discovery may result in material changes to the Schedules and Statements and inadvertent errors or omissions may exist. The Debtors may, but shall not be required to, update the Schedules and Statements as a result of the -

Vivien Leigh

Restore our Waters Forum Nov. 10 at BIG ARTS See page 9 •'(. •S1!. ^•vt " .*•" V- f \ TIME!! 1 1-1 PcunJ f.'kii.'if'LoL.'fc-i SPI"PII'.vilh Served with baked Idaho pot.ito >-^ •'- < '* -•"' B.«>J.: J •>.» ./-. corn on lh( oot- FIPIU-II Furs, i Colr.<?!,-v." &in_OQth§ cob . iwhilf-s.u|jphor. l.is>ti EVERYDAY!! s Served with French Fries & corn on the cob .islci I .nil, \ivl. Dis<ii\iT ( icdil ( .11(1- V.cr|il«.|l ; IH'.l\ 2 • Week of November 4-10, 2005 • Islander The Vunes (kolf And Tennis Club 949 Sand Castle Road • Smibel island • 472.3355 November 2005 Upcoming Vublic Events Monday - Friday Happy Hour 4:00 - 6:00pm • Enjoy»,Z for 1 well drinks, draft beer md house wine Dinner: Tuesday thru Saturday, 5 to 9pm *~ Lunch: Sunday & Saturday, 11am to 2:30pm '_,_.". Prime Rib Dinner Special Every Tuesday, 5 to 9pm Keep Lee County Beautiful Tournament Schoolhouse Theater Dining & Theater Package Scramble Format* Putting Contest . : -In The Mood 1940'sjukebox full Moon Candlelight Yoga with Brian & Skill Prizes Dinner 5 to 6:30pm 7 to 8:30pm 100.00 per person • ;' *.- Shows 8pm Nov 1st - Nov.. 26th A special Outdoor Experience by Candlelight Fee include* Matinees at 4pm on November 5th & 9th and Moonlight on the Eve of the Full Moon Crolf' Lunch • Prizes • 124 Players • .' •: . Members 40.00 - cjuest 50.00 No experience necessary 18.00 Held in the Pavilion, registration 395.1110 '••". ' - Tennis Clinic Saturday & Sunday •'•' . Members 16.00 - (juest 20.00 Thanksgiving Buffet Fasftion Show *• 1 lam to lp»n ~ W.00 inclusive 12 Noon to 5pm Dunes lennis & Cruise Wear Fashions Adults 2S.95 from the Sporty Seahorse Chihlren 12 & under 12.95 Reception 11am - Lunch & hishion show Call 4723355 for Information vt.iitrijf.-^, •i,'ii~.u.~.it. -

Your Best Source for Local Entertainment Information

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 18, 2006 Monday Evening April 24, 2006 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Wife Swap SuperNanny What About Brian Local Local Jimmy K KBSH/CBS King/Que How I Met 2 1/2 Men Christine CSI Miami Local Late Show Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Apprentice Medium Local Tonight Show Conan FOX Prison Break 24 Local Local Local Local Local Local Cable Channels A & E Flip This House 1st Person Killers Oh, Baby...Now What? Flip This House AMC First Blood Uncommon Valor First Blood ANIM Animal Precinct Miami Animal Police Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Miami Animal Police CNN Paula Zahn Now Larry King Live Anderson Cooper Larry King Norton TV DISC American Chopper American Chopper Stunt Junkies American Chopper DISN Disney Movie Raven Sis Bug Juice Lizzie Boy Meets Even E! Dr. 90210 Howard Stern The Soup ESPN Monday Night Baseball Sportscenter Fastbreak Bball Toni ESPN2 Viking Paintball Quite Frankly Paintball FAM Beautiful People Beautiful People Whose LI Whose Lin 700 Club Wildfire FX League of Extraordinary Gentleman Thief That 70's That 70's HGTV CashAttic Cash Attic Worlds M Hunters In House Hu Land Sma Dime DoubleTa CashAttic Cash Attic HIST UFO Files Digging For The Truth Deep Sea Detectives Hooked UFO Files LIFE Murder In The Hamptons Engaged To Kill Will/Grace Will/Grace Frasier Frasier MTV Wild 'N Out RW/RR & Back Made Wild 'N Out Listings: NICK SpongeBo Drake Full Hous Full Hous Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes SCI Stargate SG-1 Stargate SG-1 Stargate SG-1 Battlestar Galactica- Part 1 &2 SPIKE CSI UFC Unleashed Pros Vs.