The Life and Ministry of Donald A. Mcgavran: a Short Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Academic Calendar

> > > ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2005-2006 ACADEMIC CALENDAR FALL SEMESTER 2005 August 5 ExL registration begins for students within an 85-mile radius of the Kentucky Campus for fall 2005 31-Sept. 2 Orientation and Registration for new students, Kentucky September 6 Classes begin 6 Opening Convocation, Kentucky 8 Opening Convocation, Florida 13, 15, 20, 22 Holiness Chapels 16 Last day to drop a course with a refund; close of all registration for additional classes 30 Payment of fees due in Business Office October 18-21 Kingdom Conference Speakers: Asbury Community 21 Last day to withdraw from the institution with a prorated refund; last day to drop a course without a grade of “F” November 3-4 Ryan Lectures Speaker: • Dr. Miroslav Volf, Professor of Systematic Theology, Yale University Divinity School 18 Last day to remove incompletes (spring and summer) 21 - 25 Fall Reading Week December 4 Advent Service 6 Baccalaureate and Commencement, Wilmore 12-16 Final Exams 16 Semester ends JANUARY TERM 2006 January 3 Classes begin 5 Last day to drop a course with a refund; close of registration for addition al courses 9 ExL registration begins for students within an 85-mile radius of the Kentucky Campus for spring 2006 13 Last day to drop a course without a grade of “F” 16 Martin Luther King Day, No Classes 20 Payment of fees due in Business Office 27 Final exams, term ends Jan. 30 - Feb. 2 2006 Ministry Conference 2 Academic Calendar 3 SPRING SEMESTER 2006 February 3 Spring Orientation 6 Classes begin 15-16 Beeson Lectures Speaker: • The Reverend Jim Garlow, Senior Pastor at Skyline Church, San Diego, CA 17 Last day to drop a course with refund; close of all registration for additional courses March 3 Payment of fees due in the Business Office 9, 10 Theta Phi Lectures Speaker: • Dr. -

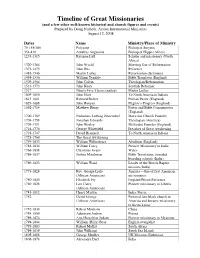

Timeline of Great Missionaries

Timeline of Great Missionaries (and a few other well-known historical and church figures and events) Prepared by Doug Nichols, Action International Ministries August 12, 2008 Dates Name Ministry/Place of Ministry 70-155/160 Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna 354-430 Aurelius Augustine Bishop of Hippo (Africa) 1235-1315 Raymon Lull Scholar and missionary (North Africa) 1320-1384 John Wyclif Morning Star of Reformation 1373-1475 John Hus Reformer 1483-1546 Martin Luther Reformation (Germany) 1494-1536 William Tyndale Bible Translator (England) 1509-1564 John Calvin Theologian/Reformation 1513-1573 John Knox Scottish Reformer 1517 Ninety-Five Theses (nailed) Martin Luther 1605-1690 John Eliot To North American Indians 1615-1691 Richard Baxter Puritan Pastor (England) 1628-1688 John Bunyan Pilgrim’s Progress (England) 1662-1714 Matthew Henry Pastor and Bible Commentator (England) 1700-1769 Nicholaus Ludwig Zinzendorf Moravian Church Founder 1703-1758 Jonathan Edwards Theologian (America) 1703-1791 John Wesley Methodist Founder (England) 1714-1770 George Whitefield Preacher of Great Awakening 1718-1747 David Brainerd To North American Indians 1725-1760 The Great Awakening 1759-1833 William Wilberforce Abolition (England) 1761-1834 William Carey Pioneer Missionary to India 1766-1838 Christmas Evans Wales 1768-1837 Joshua Marshman Bible Translation, founded boarding schools (India) 1769-1823 William Ward Leader of the British Baptist mission (India) 1773-1828 Rev. George Liele Jamaica – One of first American (African American) missionaries 1780-1845 -

The Life of Donald Mcgavran: Growing Stronger

VOL. 11 • NO.1 FALL 2019 THE LIFE OF DONALD MCGAVRAN: GROWING STRONGER Gary L. McIntosh Editor’s Note: Gary L. McIntosh has spent over a decade researching and writing a complete biography on the life and ministry of Donald A. McGavran. We are pleased to present the tenth excerpt from Donald A. McGavran: A Biography of the Twentieth Century’s Premier Missiologist (Church Leader Insights, 2015). Abstract: The 1980s were the major growth years of the Church Growth Movement in the USA. Win Arn’s Institute for American Church Growth reached its zenith, and the School of World Mission at Fuller continued to promote Church Growth thinking. Peter Wagner gradually took over the primary role as professor of church growth, as McGavran reduced his teaching load. The issue of what is the primary goal of mission—social justice or evangelism—continued to be one of McGavran’s major concerns. 120 Growing Stronger By January 1979, the Institute for American Church Growth was a major contributor to the increase in awareness of church growth among American churches. The Institute had trained more than eight thousand clergy and fifty thousand laity through pastors’ conferences and seminars. More than a million people had seen one or more films on Church Growth. One quarter million copies of Church Growth, America had been distributed, all within just five years of its inception. Arn’s adaptation of McGavran’s ideas did not happen by accident. In the early years Arn did not know much about church growth. Thus, he merely packaged Donald’s ideas in creative ways for American churches. -

Growth Within the Single-Cell Church: an Examination of the Current Attitudes and Teachings Among Church Growth Authorities

£ GROWTH WITHIN THE SINGLE-CELL CHURCH: AN EXAMINATION OF THE CURRENT ATTITUDES AND TEACHINGS AMONG CHURCH GROWTH AUTHORITIES By John D. Corcoran A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Church Growth and Cross-Cultural Studies Liberty Baptist College B. R. Lakin School of Religion April 1985 tr s LIBERTY BAPTIST COLLEGE B.R. LAKIN SCHOOL OF RELIGION THESIS APPROVAL SHEET" GRADE A THESISMENTOR~U~ RE.ll.DER READER 7 s ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A special word of appreciation is extended to my wife, Naomi, and our children, Shawn and Jason, for their love and encouragement throughout the duration of my Master's program and particularly during the time I spent completing this thesis. Gratitude is also expressed to the library staff at Liberty Baptist College and Seminary for their cooperation and assistance with my research. My appreciation also goes to Dr. Elmer L. Towns, my mentor, for his patience, wisdom, and encouragement during the many months we worked together on this project. Finally, I want to express my praise to the Lord Jesus Christ for His guidance and provision. It is a blessed privilege to serve Him as a minister of the Gospel. ii z p TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . ii Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 Statement of the Problem . 1 Statement of Purpose 3 Limitations and Methods of Research . 4 Chapter Divisions and Summaries . 4 Definition of Terms . 6 Summary . 7 II. WHAT IS A SINGLE-CELL CHURCH? 9 Sociological Perspective 9 Biblical Perspective 15 Quantitative Perspective . 18 Sl.lfillIlary • . • • • • • • • • 20 III. -

The Roots of Donald A. Mcgavran's Evangelistic Insights by Gary L. Mcintosh, D.Min, Ph.D. the Modern Emphasis on the Growth Of

The Roots of Donald A. McGavran’s Evangelistic Insights By Gary L. McIntosh, D.Min, Ph.D. The modern emphasis on the growth of the Church is attributed primarily to the pioneering work of Donald A. McGavran. A third-generation missionary, McGavran’s concern for evangelism was forged in the furnace of personal work among a poor caste of people in India during the first half of the 1900’s. Between 1937 and 1954, McGavran developed new insights on how to win people to Christ and bring them into active church membership. At first he desired to call his new missiological ideas evangelism, but found the word highly misunderstood. So he coined the term church growth as a new way to refer to evangelism, hoping that he could invest his new terminology with fresh meaning. To McGavran, church growth, or evangelism, simply meant the process of winning people to Christ and incorporating them into a local church where they could grow in their newfound faith. Toward the end of his life he began using a new term—effective evangelism—to reference what he was advocating. In addition to this basic view of evangelism McGavran added an emphasis on keeping track of results, focusing on receptive people, and using pragmatic methods. Like other major schools of thought, McGavran did not develop his ideas on evangelism out of nothing. In reality his evangelistic insights were the result of many forces that converged in his life over a number of years. What McGavran called church growth, or effective evangelism, has occurred throughout the Christian era, of course, and is not really new. -

The Legacy of Donald A. Mcgavran

The Legacy of Donald A. McGavran George G. Hunter III onald Anderson McGavran was bornin Damoh, India, 3. What are the factors that can make the Christian faith a D on December 15,1897, the second child of missionaries movement among some populations? John Grafton McGavran and Helen Anderson McGavran. He 4. What principles of church growth are reproducible? was raised in central India with two sisters, Joyce and Grace, and a brother, Edward. Joyce and Grace eventually pursued voca McGavranalso developed a field research method for study tions in the United States, while the brothers remained in India ing growing (and nongrowing) churches, employing historical Edward as a physician and public health pioneer, and Donald as analysis, observations, and interviews to collect data for analysis a third-generation missionary of the ChristianChurch (Disciples and case studies. From 1964 to 1980 McGavran published re of Christ). Donald McGavran received his higher education in search findings and advanced church growthideas in the Church the United States, attending ButlerUniversity (B.A.),Yale Divin Growth Bulletin and other publications. By the mid 1980s, the ity School (B.D.), the former College of Mission, Indianapolis (M.A.), and, following two terms in India, Columbia University (Ph.D.). McGavran asked, "When a McGavran invested his "firstcareer" in India as an educator, field executive, evangelist, church planter, and researcher. In the church is growing, why is it early 1930s, McGavran began to wonder why some churches growing?" reached people and grew while others declined. He pointedly asked, "When a church is growing, why is it growing?" Discov ering the answers to that question became his obsession. -

The Legacy of Donald Mcgavran: a Forum Edited by IJFM Editorial Staff

Stewarding Legacies in Mission The Legacy of Donald McGavran: A Forum edited by IJFM Editorial Staff n August of 2013, the Ralph D. Winter Research Center (RDWRC) hosted a forum on the legacy of Donald McGavran. During the second half of the 20th century, McGavran became a global spokesman for church growth. He was a third generation missionary to India, and returned thereI with his wife, Mary, for some three decades of service. His observations and study of people movements to Christ in India (and in other parts of the world) were sparked by the 1934 publication of J. Waskom Pickett’s Christian Mass Movements in India: A Study with Recommendations. In 1955, this inter- est led to the publication of McGavran’s seminal book, The Bridges of God, and moved him into global significance in the field of missiology. Last summer’s forum was instigated by the recent biography published by Vern Middleton, Donald McGavran: His Life and Ministry—An Apostolic Vision for Reaching the Nations (William Carey Library, 2011). The book covers McGavran’s life until he became the founding Dean of the School of World Mission at Fuller Seminary in the 1960s. Greg H. Parsons, director of the RDWRC, led the lively roundtable discussion over the course of two days (a list of participants is provided on p. 62). The IJFM has now edited those discussions for the general mission public with the hope of making McGavran’s legacy more accessible to a new generation of mission leaders. Plans are being made for a similar forum in 2015 on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of McGavran’s passing in 1990. -

Howard Peskett, "Review Article: Timothy Yates, Christian Mission In

EQ 71:2 (1999). 151-155 Howard Peskett Review Article: Timothy Yates, Christian mission in the twentieth century Timothy Yates' important study of contemporary mzsswnary thinking is discussed fly H oward Peskett who is currently teaching in Trinity College, Bristol after previously working in theological education in Singapore. Key words: Mission; theology; ecumenism. Could one Western author deal with the whole global scope and story of Christian (notjust Protestant) mission in the whole of this tumultu ous century in the 275 pages of Christian mission in the twentieth century (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp xvi + 275, paper back edition 1996)? It would demand encyclopaedic knowledge and miraculous skills of condensation! In fact, despite his title, Yates has attempted no such thing: we must take the title as one of the signs that hangs over the major alleys of a supermarket-as a brief summary of the tasty delights stocked below. The book started as lectures in 'Mission and Ecumenism' in Durham and this orientation marks the three strands which it contains: (a) Yates' historical interest shows in his surveys of some ofthe most important mission conferences held this century, in particular New York 1900, Edinburgh 191O,Jerusalem 1928, Tambaram 1938, CWME 1963, Vatican 11, Lausanne 1974 and Nairobi 1975. (b) Yates' biographical interest is revealed in his portraits of some of the most important missions writers and statesmen (there is almost nothing about women in this book although he notes the prominence of women at New York) of the century, in particular Hendrik Kraemer, John R. Mott, Step hen C. -

FULL ISSUE (48 Pp., 2.3 MB PDF)

Vol. 16, No.1 nternatlona• January 1992 ctln• Our Mission Legacy hallmark of this journal is its award-winning mission Crowther, "the most widely known African Christian of the A "legacy" series. In this issue, A. Christopher Smith nineteenth century." Author Andrew F. Walls underlines the offers a fresh assessment of our debt to William Carey, who, two pointed ways in which the dynamics surrounding Crowther's hundred years ago, helped launch the modern missionary move ministry anticipated the central issues of indigenous leadership ment with the publication of his An Enquiry into the Obligations of down to the present time. Christians, to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens. The INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN is grateful for the opportunity Wilbert R. Shenk inaugurated the legacy series in April 1977, to recall and share our legacy. with a study of the life and work of Henry Venn, father of the indigenous church, three-self principles: self-support, self-gov ernment, and self-propagation. In the last fifteen years the INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN has profiled sixty-seven individuals who contributed in a formative, pioneering way to the theory and practice of the Christian world mission. Over the next several On Page years the editors foresee a comparable number of additional leg acy articles, examining such figures as Charles H. Brent, Amy Carmichael, Orlando Costas, Melvin Hodges, J. C. Hoekendijk, 2 The Legacy of William Carey Jacob [ocz, John A. Mackay, Donald A. McGavran, Robert A. Christopher Smith Moffatt, Constance E. Padwick, Pope Pius XI, Pandita Ramabai, 10 "Behold, I am Doing a New Thing" Ruth Rouse, Charles Simeon, Alan R. -

Donald Mcgavran's Early Years

VOL. 6 • NO. 2 • WINTER 2015 • 216–236 DONALD MCGAvraN’S EARLY YeARS Gary L. McIntosh Gary L. McIntosh has spent the last twelve years researching and writing a complete biography on the life and ministry of Donald A. McGavran. We are pleased to present here the second of several excerpts from the forthcoming biography. Abstract Donald McGavran was born in 1897. This article covers the years from his birth until 1923 when he and Mary McGavran sailed to India. His early life as the child of missionaries, his secondary education in the United States, service in WWI, college education at Butler Uni- versity, seminary days at Yale Divinity School, and masters work at the College of Mission are presented. Donald Anderson McGavran was born in Damoh, India, on December 15, 1897, in the red brick, two-story home John McGavran had helped build for the Rambos.1 Appearing somewhat like a medieval castle, the home today has a long staircase leading to the second floor in the back, with a small courtyard in front of two gated doors on the ground floor. Encircling the roof is a brick fence about three feet high, giving the house its castle-like appearance. A low sloping roofline overhangs the front of the house, provid- ing a shady place to sit during the hot afternoons. 1 McGavran’s birth date is listed as 1898 in some records, which is most likely a clerical error. 216 DONALD MCGAVran’S EARLY YEARS Donald’s parents, John and Helen McGavran, were living in Damoh pri- marily due to the famine that had hit central India. -

What Is the Church Growth School of Thought

344 | 11th Biennial Meeting 1972 What is the Church Growth School of Tought Donald McGavran Fuller Teological Seminary INTRODUCTORY REMARKS For more than ffteen years I have been developing the inter- disciplinary feld known as the Church Growth School of Tought, defning its limitations, formulating its concepts, developing or borrowing the methods proper to it and discriminating its fndings. I have written a number of church growth books, supervised many church growth researches in Asia, Africa and Latin America, had close connection with researches in church growth in Europe and North America, edited the Church Growth Bulletin for eight years, and built up a missions faculty devoted to classical Christian mission – which is to say, to the basic tenets of church growth. Yet I have never stopped formally to answer the question posed by the title of this paper – What Is the Church Growth School of Tought? I am grateful to Professor Pyke and the Association of Professors of Mission for giving me the opportunity to speak to the subject. I am also delighted that three other members of our seven-man faculty are here. Te Church Growth School of Tought is a joint production. I have, in fact, played a rather small part in it. Te men on our faculty have played a large part. Alan Tippett, Arthur Glasser, Ralph Winter, Charles Kraft, Peter Wagner, Edwin Orr, and Roy Shearer, have all added signifcantly to the complex. So have men not citizens of the United States – like Dr. Peter Coterell of the great Sudan Interior Mission and David Barrett of the Anglican Church Missionary Society – Church Growth is much bigger than Pasadena. -

Effective Evangelism”

VOL. 2 • NO. 1 • SUMMER 2010 DONALD MCGAVRAN’S THEOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS 50 FOR “EFFECTIVE EVANGELISM” Jeff K. Walters abstract From its inception, the Church Growth Movement, as espoused by its “father,” Donald A. McGavran, was focused on “effective evangelism.” The purpose of this article is to identify McGavran’s theology of evangelism as revealed in his published writings. While he may never have delineated a precise theology of evangelism, one can [nd in McGavran’s writings an orthodox, if sometimes incomplete, system regarding the working of God in the salvation of men and women. The article investigates McGavran’s views on Scripture, the content and proclamation of the gospel, and on key soteriological issues. For two thousand years, pastors, theologians, and laypeople alike have sought how best to answer the question, “What must I do to be saved?” The content of that response is the heart of the gospel. Perhaps missionaries, in response to different cultures and beliefs, have sought most fervently to understand the message of Great Commission proclamation. One such man was Donald Anderson McGavran, missionary to India, the “father of church growth,” and “founder of the Church Growth Movement.”1 Kenneth Mulholland argues that “probably no 1 Thom S. Rainer, The Book of Church Growth: History, Theology, and Principles (Nashville: Broadman and Holman Publishers, 1993), 24–25. DONALD MCGAVRAN’S THEOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS FOR “EFFECTIVE EVANGELISM” one person has inYuenced evangelical missions in [the twentieth] century as much as McGavran.”2 The purpose of this article is to identify Donald McGavran’s theology of evangelism, primarily through a selection of his published writings.3 Two primary reasons stand out for such a study.