From the Hicksites to the Progressive Friends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Fox's Footsteps: Planning 1652 Country Quaker Pilgrimages 2019

in fox's footsteps: planning 1652 country quaker pilgrimages 2019 Why come “If you are new to Quakerism, there can be no on a better place to begin to explore what it may mean Quaker for us than the place in which it began. pilgrimage? Go to the beautiful Meeting Houses one finds dotted throughout the Westmorland and Cumbrian countryside and spend time in them, soaking in the atmosphere of peace and calm, and you will feel refreshed. Worship with Quakers there and you may begin to feel changed by the experience. What you will find is a place where people took the demands of faith seriously and were transformed by the experience. In letting themselves be changed, they helped make possible some of the great changes that happened to the world between the sixteenth and the eighteenth centuries.” Roy Stephenson, extracts from ‘1652 Country: a land steeped in our faith’, The Friend, 8 October 2010. 2 Swarthmoor Hall organises two 5 day pilgrimages every year Being part of in June/July and August/September which are open to an organised individuals, couples, or groups of Friends. ‘open’ The pilgrimages visit most of the early Quaker sites and allow pilgrimage individuals to become part of an organised pilgrimage and worshipping group as the journey unfolds. A minibus is used to travel to the different sites. Each group has an experienced Pilgrimage Leader. These pilgrimages are full board in ensuite accommodation. Hall Swarthmoor Many Meetings and smaller groups choose to arrange their Planning own pilgrimage with the support of the pilgrimage your own coordination provided by Swarthmoor Hall, on behalf of Britain Yearly Meeting. -

Fact Sheet on North Pacific Yearly Meeting's Relationship to Other

Information Sheet on North Pacific Yearly Meeting’s relationship to other Yearly Meetings and Associations of Yearly Meetings June 2013 Associations of Yearly Meetings Conservative Friends Conservative Friends are comprised of three yearly meetings: Iowa Friends Conservative, Ohio Friends Conservative, and North Carolina Friends Conservative. Although there is no official umbrella organization for Conservative Friends, Ohio Yearly Meeting hosts a gathering of the Wider Fellowship of Conservative Friends once every other year, which all Friends are welcome to attend. Conservative Friends do not have a publications program. They do host Quaker Spring, a gathering where people explore Quaker History and share meaningful dialogues. Their worship is unprogrammed but strongly Christ-centered. North Pacific Yearly Meeting is descended from Friends who left Iowa Yearly Meeting to come to California, and we recognize these historic ties that we share with Conservative Friends. There has been interest, especially among younger Friends, in learning from Conservative Friends about Quaker heritage and our shared roots. We found on our committee interest in closer ties with Conservative Friends, but could see no easy way to do this. We discussed having people from the Quaker Spring leadership come to visit our Annual Session or our local meetings. The only other avenue we can find is simply to send an observer or representative to each of the three Conservative yearly meetings and/or to the Wider Fellowship of Conservative Friends. Evangelical Friends Church International Evangelical Friends Church International is the organization that represents evangelical Friends throughout the world. They are decentralized, with regions and yearly meetings operating autonomously. -

Nomination Form

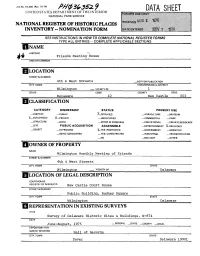

jrm No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) />#$ 36352.9 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DATA SHEET NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Friends Meeting House AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 4th & West Streets -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Wilmington VICINITY OF 1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 New Castle 002 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X—BUILDING(S) X.-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE __BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X_RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED __YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO .-MILITARY —OTHER: (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Wilmington Monthly Meeting of Friends STREET & NUMBER 4th & West Streets CITY. TOWN STATE Wilmington VICINITY OF Delaware LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. New Castle Court House STREET & NUMBER Public Building, Rodney Square CITY, TOWN STATE Wilmington Delaware 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Delaware Historic Sites & Buildings, N-874 DATE June-August, 1975 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Hall of Records CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware 19901 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^-EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE_ —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Friends Meeting House, majestically situated on Quaker Hill, was built between 1815 and 1817 and has changed little since it was built. What change has occurred has not altered the integrity of the building. -

History-Iowa Yearly Meeting 8/1/17, 1�14 PM

History-Iowa Yearly Meeting 8/1/17, 114 PM BRIEF HISTORY OF IOWA YEARLY MEETING OF FRIENDS (CONSERVATIVE) A. QUAKER HISTORY THE ROOTS OF QUAKERISM The Religious Society of Friends had its beginnings in mid-Seventeenth Century England. The movement grew out of the confusion and uncertainty which prevailed during the closing years of the Puritan Revolution and which culminated in the overthrow of the English monarchy. During the long Medieval period, the English Church, like other national churches throughout western Europe, had been subject to the authority of the Pope and the Church of Rome. However, throughout the later Middle Ages dissident groups such as the Lollards in Fourteenth Century England questioned the teaching and authority of the Roman Church. All of northern and western Europe was profoundly affected by the Protestant Reformation. Its particular origin may be traced to about 1519 when Martin Luther began his protest in Germany. While Lutheranism supplanted Roman Catholic control in much of north central Europe, another Protestant movement led by John Calvin became dominant in the Netherlands, in Scotland, and among the Huguenots in France. The Anabaptists constituted still another Protestant element. In England, however, the Protestant movement had a somewhat different history. About 1534 King Henry VIII broke with the Roman church, with the immediate personal purpose of dissolving his first marriage and entering into another. As a result of this break with Rome, the numerous abbeys throughout England were closed and plundered and their extensive land holdings were distributed among the king's favorites. The Catholic church enjoyed a period of reascendancy during the reign of Queen Mary, only to be replaced as the established church by the Church of England during the long reign of Queen Elizabeth I. -

MERION FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

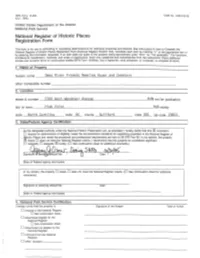

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 MERION FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: MERION FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 615 Montgomery Avenue Not for publication:_ City/Town: Merion Station Vicinity:_ State: PA County: Montgomery Code: 091 Zip Code: 19006 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): X Public-Local: _ District: _ Public-State: _ Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 _ buildings 1 _ sites _ structures _ objects Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 MERION FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Historical Note on the Term “Conservative” As Applied to Friends Discussion Draft - 11/1/2019

Historical Note on the Term “Conservative” as Applied to Friends Discussion Draft - 11/1/2019 For half a century following the events of 1903-1904, each of the two groups of Friends in North Carolina considered themselves the authentic continuation of the earlier North Carolina Yearly Meeting. To distinguish between the identically-named yearly meetings, our yearly meeting added the location of yearly meeting sessions after its name: minute books were titled Minutes of North Carolina Yearly Meeting held at Cedar Grove in the town of Woodland, Northampton County, North Carolina. When it was necessary to refer to “the other body” in the minutes, it too was often identified by the location of its annual sessions, as in “North Carolina Yearly Meeting held at Guilford College.” Outside of North Carolina, the term “Conservative” came to be used to refer to several yearly meetings that were the result of separations in the mid-to-late 1800s, including the Wilburite yearly meetings (e.g., Ohio Yearly Meeting at Barnesville and New England Yearly Meeting), the second wave that included Western Yearly Meeting of Conservative Friends and Iowa Yearly Meeting (Conservative), and finally, North Carolina Yearly Meeting held at Cedar Grove. In the mid-1960s, Friends in North Carolina Yearly Meeting held at Cedar Grove began to use the term to refer to these yearly meetings as a group, although not as part of our yearly meeting’s name. There does not appear to be a formal minute incorporating the word “Conservative” into the name of our yearly meeting. However, the use of the word “Conservative” in the name appears to have begun in 1966. -

Friends Meeting House, Brigflatts

Friends Meeting House, Brigflatts Brigflatts, Sedbergh, LA10 5HN National Grid Reference: SD 64089 91155 Statement of Significance Brigflatts has exceptional heritage significance as the earliest purpose-built meeting house in the north of England, retaining a richly fitted interior and an unspoilt rural setting. The vernacular building is Grade 1 listed, and important as a destination for visitors as well as a meeting house for Quaker worship. Evidential value The meeting house has high evidential value for its fabric which incorporates historic joinery and fittings of several phases, from the early eighteenth century through to the early 1900s, illustrating incremental repair and renewal. The burial ground and ancillary stable and croft buildings also have archaeological potential. Historical value The site is associated with a 1652 visit by George Fox to the area, and to the growth of Quakerism in this remote rural area. The meeting house was built in 1674-75 and fitted out over the following decades, according to Quaker requirements and simple taste. The burial ground has been in continuous use since 1656 and is the burial place of the poet Basil Bunting. The building and place has exceptional historical value. Aesthetic value The form and design of the building is typical of late seventeenth century vernacular architecture in this area, constructed in local materials and expressing Friends’ approach to worship. The attractive setting of the walled garden, paddock and outbuildings adds to its aesthetic significance. The exterior, interior spaces and historic fittings ad furnishings have exceptional aesthetic value. Communal value The meeting house is primarily a place for Quaker worship but is important to visitors to this western part of the Yorkshire Dales. -

Friends Meeting House, Kirby Stephen

Friends Meeting House, Preston Patrick Preston Patrick, Milnthorpe, LA7 7QZ National Grid Reference: SD 54228 84035 Statement of Significance Preston Patrick Meeting House has high significance as the site of a meeting house and burial ground since the 1690s. The current building is a modest, attractive example of a Victorian meeting house with attached cottage, incorporating some earlier joinery and structure. The site also contains a cottage, gig house, stable and schoolroom block and the tranquil rural setting in 1652 Country is part of its importance. Evidential value The meeting house has high evidential value, as a building incorporating fabric from the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The site, including the burial ground is likely to have archaeological potential. Historical value Quakerism has a long history in this area; George Fox spoke nearby in 1652 and the Westmorland Seekers were active in Preston Patrick; Mabel Benson, John Camm, John Audland and other Westmorland Seekers are buried in the burial ground. The building has high historical significance as a late 17th century meeting house, rebuilt in 1876. The gig house, stables and schoolroom also have high historical value and illustrate past Quaker transport provision and commitment to local education. Aesthetic value The meeting house has medium aesthetic significance as a modest example of a Victorian meeting house that retains some earlier joinery, but the site as a whole has high aesthetic value for the tranquil rural setting and the ensemble of historic Quaker buildings. Communal value The meeting house has high communal value as the local focus for Friends since 1691, but it is not well used by the community outside the Friends due to its rural location. -

Download Download

43 THE BUILDING OF SETTLE MEETING HOUSE IN 1678 Settle Friends Meeting House, in Kirkgate, Settle, North Yorkshire, has been in continuous use by Quakers since its building in 1678. David Butler, in The Quaker Meeting Houses of Britain, records that a parcel of ground in what was then known as Howson's Croft was first acquired by Quakers in 1659, and was confirmed in 1661 as having' a meeting house and stable erected thereon'.1 The indenture itself, dated 4 September 1661, is not in fact quite so specific, referring only to the land having 'houses and other grounds', but it makes very clear that the intention in 1659 was (and remained) to provide a burial place and 'a free meeting place for freinds to meet in'.2 The parcel of ground, 18 x 27 yards in extent, had been purchased from William Holgate on 2 March 1659 by John Kidd, John Robinson, Christopher Armetstead, John Kidd Uunior], and Thomas Cooke, 'tradesmen'. The deed of 1661 formally assigned the property (for a peppercorn rent) to two other Quakers, Samuel Watson of Stainforth Hall, gentleman, and John Moore of Eldroth, yeoman, 'in the behalfe of themselves and all other freinds belonging to Settle meeting'. That is to say, Watson and Moore became the first trust~s of the property. Settle Preparative Meeting minutes do not survive before 1700, and so it is not possible to say whether Settle Friends used the existing buildings on the site for their meetings. That they continued to meet in each other's houses is clear from Settle Monthly Meeting Sufferings, which record a number of fines for holding meetings in the years 1670-72 (following the Second Conventicle Act of 1670), Samuel Watson being hit particularly hard.3 However, the question of a purpose-built meeting house is raised soon afterwards: a Monthly Meeting minute dated 5th of 12th month 1672 (i.e. -

From Plainness to Simplicity: Changing Quaker Ideals for Material Culture J

Chapter 2 From Plainness to Simplicity: Changing Quaker Ideals for Material Culture J. William Frost Quakers or the Religious Society of Friends began in the 1650s as a response to a particular kind of direct or unmediated religious experience they described metaphorically as the discovery of the Inward Christ, Seed, or Light of God. This event over time would shape not only how Friends wor shipped and lived but also their responses to the peoples and culture around them. God had, they asserted, again intervened in history to bring salvation to those willing to surrender to divine guidance. The early history of Quak ers was an attempt by those who shared in this encounter with God to spread the news that this experience was available to everyone. In their enthusiasm for this transforming experience that liberated one from sin and brought sal vation, the first Friends assumed that they had rediscovered true Christianity and that their kind of religious awakening was the only way to God. With the certainty that comes from firsthand knowledge, they judged those who op posed them as denying the power of God within and surrendering to sin. Be fore 1660 their successes in converting a significant minority of other English men and women challenged them to design institutions to facilitate the ap proved kind of direct religious experience while protecting against moral laxity. The earliest writings of Friends were not concerned with outward ap pearance, except insofar as all conduct manifested whether or not the person had hearkened to the Inward Light of Christ. The effect of the Light de pended on the previous life of the person, but in general converts saw the Light as a purging as in a refiner’s fire (the metaphor was biblical) previous sinful attitudes and actions. -

Flavors” of Quakers in the U.S

“Flavors” of Quakers in the U.S. Today It is hard to delineate clear cut branches of American Quakerism because different branches define themselves differently, and because there is much variation and overlap. You can sort Quakers in several ways: by our qualities and characteristics, by the major affiliating organizations we associate with, or by historical lineage (which group is an offshoot of which other group). These different ways of categorizing us will produce similar, but not identical groups. Following is a rough sorting. Liberal Friends Generally, liberal Friends practice unprogrammed worship, do not have formal clergy, and emphasize the authority of the Light Within. They value universalism, meaning they include members identifying with a variety of theological traditions, such as Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, Wicca, and increasingly nontheism. You find them most often in the eastern and western parts of the U.S. and in college towns. There are two major groups of Liberal Friends: ● Those affiliated with Friends General Conference (see www.fgcquaker.org). These meetings often trace their roots back to the Hicksite side of the major division (see historic notes below) but there are other histories mixed in. FGC includes yearly meetings in the U.S. and Canada. ● Independent or Western Friends. Located mostly in the Western part of the United States, these Friends are sometimes called “Beanites,” because they trace their roots, to some degree, to the leadership of Joel and Hannah Bean, who came out of the Orthodox side of the major division, but parted ways. Independent Friends have no affiliating organization, but they do have a magazine, Western Friend (https://westernfriend.org). -

Historic Name __ -=D:...:E:...:E::...R:P

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Gel. 1990) United States National Park Service This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. historic name __-=D:....:e:....:e::...r:p;....-..:....R:....;..i .-.:..v=e~r--=-Fr=--l..:....;· e::..:.n.:...,:d:::..;:s=---.:...M=e:....::e-=t....:.i ..:..:cn...;;J.q--,-,-H..:::..,o =u s~e=--..:a::...:.n.:....::d::..-..;::Cc..:::e...:..:..m=e-=-t=e ..:....;ry-'--- __________ other names/site number _________________________________ street & number_-=5~3=O=O~W=e~st~W=e=n~d=o....:.v=e~r~A~v~e=n=u=e~ ___________~N~ not for publication city or town __--!.H.!....!ic....;ql.!-'h~P=o..!...!i n'-!-t~ ____________________Nm vicinity state _...wN=o-'-r=t!..!..h....:C=a::w.r-"'o:.....!.l-!..i..!..!.n=.,a __· code --.fiL county _-=G=-u-,-;'.!.-f'-"o::..,.:.r.....:::d=-- ____ code J2B.L zip code 28601 As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this !Xl nomination o request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of .