Katie Mitchell and Rena Schlachter Join Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRIORITY GRASSLANDS INITIATIVE Methodology for Identifying Priority Grasslands

PRIORITY GRASSLANDS INITIATIVE Methodology for Identifying Priority Grasslands September 2007 Building a Scientific Framework and Rationale for Sustainable Conservation and Stewardship Grasslands Conservation Council of British Columbia 954A Laval Crescent Kamloops, BC V2C 5P5 Phone: (250) 374-5787 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bcgrasslands.org Cover photo: Prickly-pear cactus by Richard Doucette Grasslands Conservation Council of British Columbia i Table of Contents Executive Summary .....................................................................................................................................i Acknowledgements .....................................................................................................................................ii Introduction.................................................................................................................................................1 Methodology Overview...............................................................................................................................2 Methodology Stages ....................................................................................................................................5 Stage 1: Initial GIS Data Gathering, Preparation and Analysis................................................................ 5 Stage 2: Expert Input .............................................................................................................................. 10 Stage 3: Assessment of Recreational -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes Among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Kristina Marie Gill Committee in charge: Professor Michael A. Glassow, Chair Professor Michael A. Jochim Professor Amber M. VanDerwarker Professor Lynn H. Gamble September 2015 The dissertation of Kristina Marie Gill is approved. __________________________________________ Michael A. Jochim __________________________________________ Amber M. VanDerwarker __________________________________________ Lynn H. Gamble __________________________________________ Michael A. Glassow, Committee Chair July 2015 Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California Copyright © 2015 By Kristina Marie Gill iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my Family, Mike Glassow, and the Chumash People. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people who have provided guidance, encouragement, and support in my career as an archaeologist, and especially through my undergraduate and graduate studies. For those of whom I am unable to personally thank here, know that I deeply appreciate your support. First and foremost, I want to thank my chair Michael Glassow for his patience, enthusiasm, and encouragement during all aspects of this daunting project. I am also truly grateful to have had the opportunity to know, learn from, and work with my other committee members, Mike Jochim, Amber VanDerwarker, and Lynn Gamble. I cherish my various field experiences with them all on the Channel Islands and especially in southern Germany with Mike Jochim, whose worldly perspective I value deeply. I also thank Terry Jones, who provided me many undergraduate opportunities in California archaeology and encouraged me to attend a field school on San Clemente Island with Mark Raab and Andy Yatsko, an experience that left me captivated with the islands and their history. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Chapter 1 the California Flora

CHAPTER 1 THE CALIFORNIA FLORA The Californian Floristic Province California is a large state with a complex topography and a great diversity of climates and habitats,resulting in a very large assemblage of plant species that vary in size and include both the world’s largest trees and some of the smallest and most unique plant species. In order to create manageable units for plant investigations, botanists have divided the continental landform into geographic units called floristic provinces. These units reflect the wide variations in natural landscapes and assist botanists in predicting where a given plant might be found. Within the borders of California, there are three floristic provinces, each extending beyond the state’s political boundaries. The California Floristic Province includes the geographi- cal area that contains assemblages of plant species that are more or less characteristic of California and that are best de- veloped in the state.This province includes southwestern Ore- gon and northern Baja California but excludes certain areas of the southeastern California desert regions, as well as the area of the state that is east of the Sierra Nevada–Cascade Range axis (map 1).The flora of the desert areas and those east of the Sierra Nevada crest are best developed outside the state, and therefore, parts of the state of California are not in the Cali- fornia Floristic Province. The Great Basin Floristic Province includes some of the area east of the Sierra Nevada and some regions in the northeastern part of the state, although some botanists consider the latter area to belong to another distinct floristic province, the Columbia Plateau Floristic Province. -

Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO BOTANY 0 NCTMBER 52 Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae Harold Robinson, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, andJames F. Weedin SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS City of Washington 1981 ABSTRACT Robinson, Harold, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, and James F. Weedin. Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae. Smithsonian Contri- butions to Botany, number 52, 28 pages, 3 tables, 1981.-Chromosome reports are provided for 145 populations, including first reports for 33 species and three genera, Garcilassa, Riencourtia, and Helianthopsis. Chromosome numbers are arranged according to Robinson’s recently broadened concept of the Heliantheae, with citations for 212 of the ca. 265 genera and 32 of the 35 subtribes. Diverse elements, including the Ambrosieae, typical Heliantheae, most Helenieae, the Tegeteae, and genera such as Arnica from the Senecioneae, are seen to share a specialized cytological history involving polyploid ancestry. The authors disagree with one another regarding the point at which such polyploidy occurred and on whether subtribes lacking higher numbers, such as the Galinsoginae, share the polyploid ancestry. Numerous examples of aneuploid decrease, secondary polyploidy, and some secondary aneuploid decreases are cited. The Marshalliinae are considered remote from other subtribes and close to the Inuleae. Evidence from related tribes favors an ultimate base of X = 10 for the Heliantheae and at least the subfamily As teroideae. OFFICIALPUBLICATION DATE is handstamped in a limited number of initial copies and is recorded in the Institution’s annual report, Smithsonian Year. SERIESCOVER DESIGN: Leaf clearing from the katsura tree Cercidiphyllumjaponicum Siebold and Zuccarini. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Chromosome numbers in Compositae, XII. -

THE JEPSON GLOBE a Newsletter from the Friends of the Jepson Herbarium

THE JEPSON GLOBE A Newsletter from the Friends of The Jepson Herbarium VOLUME 26 NUMBER 1, Spring 2016 Curator’s Column: Museomics The Jepson Manual: Vascular Reveals Secrets of the Dead Plants of California, Second By Bruce G. Baldwin Edition: Supplement III Over the last decade, herbaria By Bruce G. Baldwin have received well-deserved public- The latest set of revisions to The Jep- ity as treasure troves of undiscovered son Manual, second edition (TJM2) and biodiversity, with the recognition that the Jepson eFlora was released online most “new” species named in the last in December 2015. The rapid pace of half-century have long resided in col- discovery and description of vascular lections prior to their detection and plant taxa that are new-to-science for original description. The prospect also California and the rarity and endanger- has emerged for unlocking the secrets of ment of most of those new taxa have plants and other organisms that no lon- warranted prioritization of revisions ger share our planet as living organisms that incorporate such diversity — and and, sadly, reside only in collections. Map of California, split apart to show newly introduced, putatively aggressive Technological advances that now al- the Regions of the Jepson eFlora. invasives — so that detection of such low for DNA sequencing on a genomic Source: Jepson Flora Project. plants in the field and in collections scale also are well suited for studying Regional dichotomous keys now is not impeded. The continuing taxo- old, highly degraded specimens, as re- nomic reorganization of genera and, to cent reconstruction of the Neanderthal available for the Jepson eFlora some extent, families in order to reflect genome has shown. -

The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition Supplement II December 2014

The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition Supplement II December 2014 In the pages that follow are treatments that have been revised since the publication of the Jepson eFlora, Revision 1 (July 2013). The information in these revisions is intended to supersede that in the second edition of The Jepson Manual (2012). The revised treatments, as well as errata and other small changes not noted here, are included in the Jepson eFlora (http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/IJM.html). For a list of errata and small changes in treatments that are not included here, please see: http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/JM12_errata.html Citation for the entire Jepson eFlora: Jepson Flora Project (eds.) [year] Jepson eFlora, http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/IJM.html [accessed on month, day, year] Citation for an individual treatment in this supplement: [Author of taxon treatment] 2014. [Taxon name], Revision 2, in Jepson Flora Project (eds.) Jepson eFlora, [URL for treatment]. Accessed on [month, day, year]. Copyright © 2014 Regents of the University of California Supplement II, Page 1 Summary of changes made in Revision 2 of the Jepson eFlora, December 2014 PTERIDACEAE *Pteridaceae key to genera: All of the CA members of Cheilanthes transferred to Myriopteris *Cheilanthes: Cheilanthes clevelandii D. C. Eaton changed to Myriopteris clevelandii (D. C. Eaton) Grusz & Windham, as native Cheilanthes cooperae D. C. Eaton changed to Myriopteris cooperae (D. C. Eaton) Grusz & Windham, as native Cheilanthes covillei Maxon changed to Myriopteris covillei (Maxon) Á. Löve & D. Löve, as native Cheilanthes feei T. Moore changed to Myriopteris gracilis Fée, as native Cheilanthes gracillima D. -

Plant List for Web Page

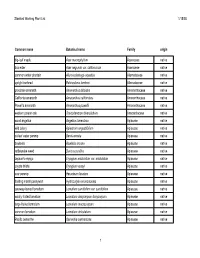

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

Download The

SYSTEMATICA OF ARNICA, SUBGENUS AUSTROMONTANA AND A NEW SUBGENUS, CALARNICA (ASTERACEAE:SENECIONEAE) by GERALD BANE STRALEY B.Sc, Virginia Polytechnic Institute, 1968 M.Sc, Ohio University, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Botany) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA March 1980 © Gerald Bane Straley, 1980 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department nf Botany The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 26 March 1980 ABSTRACT Seven species are recognized in Arnica subgenus Austromontana and two species in a new subgenus Calarnica based on a critical review and conserva• tive revision of the species. Chromosome numbers are given for 91 populations representing all species, including the first reports for Arnica nevadensis. Results of apomixis, vegetative reproduction, breeding studies, and artifi• cial hybridizations are given. Interrelationships of insect pollinators, leaf miners, achene feeders, and floret feeders are presented. Arnica cordifolia, the ancestral species consists largely of tetraploid populations, which are either autonomous or pseudogamous apomicts, and to a lesser degree diploid, triploid, pentaploid, and hexaploid populations. -

Ventura County Plant Species of Local Concern

Checklist of Ventura County Rare Plants (Twenty-second Edition) CNPS, Rare Plant Program David L. Magney Checklist of Ventura County Rare Plants1 By David L. Magney California Native Plant Society, Rare Plant Program, Locally Rare Project Updated 4 January 2017 Ventura County is located in southern California, USA, along the east edge of the Pacific Ocean. The coastal portion occurs along the south and southwestern quarter of the County. Ventura County is bounded by Santa Barbara County on the west, Kern County on the north, Los Angeles County on the east, and the Pacific Ocean generally on the south (Figure 1, General Location Map of Ventura County). Ventura County extends north to 34.9014ºN latitude at the northwest corner of the County. The County extends westward at Rincon Creek to 119.47991ºW longitude, and eastward to 118.63233ºW longitude at the west end of the San Fernando Valley just north of Chatsworth Reservoir. The mainland portion of the County reaches southward to 34.04567ºN latitude between Solromar and Sequit Point west of Malibu. When including Anacapa and San Nicolas Islands, the southernmost extent of the County occurs at 33.21ºN latitude and the westernmost extent at 119.58ºW longitude, on the south side and west sides of San Nicolas Island, respectively. Ventura County occupies 480,996 hectares [ha] (1,188,562 acres [ac]) or 4,810 square kilometers [sq. km] (1,857 sq. miles [mi]), which includes Anacapa and San Nicolas Islands. The mainland portion of the county is 474,852 ha (1,173,380 ac), or 4,748 sq. -

USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region Sensitive Plant Species by Forest

USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region 1 Sensitive Plant Species by Forest 2013 FS R5 RF Plant Species List Klamath NF Mendocino NF Shasta-Trinity NF NF Rivers Six Lassen NF Modoc NF Plumas NF EldoradoNF Inyo NF LTBMU Tahoe NF Sequoia NF Sierra NF Stanislaus NF Angeles NF Cleveland NF Los Padres NF San Bernardino NF Scientific Name (Common Name) Abies bracteata (Santa Lucia fir) X Abronia alpina (alpine sand verbena) X Abronia nana ssp. covillei (Coville's dwarf abronia) X X Abronia villosa var. aurita (chaparral sand verbena) X X Acanthoscyphus parishii var. abramsii (Abrams' flowery puncturebract) X X Acanthoscyphus parishii var. cienegensis (Cienega Seca flowery puncturebract) X Agrostis hooveri (Hoover's bentgrass) X Allium hickmanii (Hickman's onion) X Allium howellii var. clokeyi (Mt. Pinos onion) X Allium jepsonii (Jepson's onion) X X Allium marvinii (Yucaipa onion) X Allium tribracteatum (three-bracted onion) X X Allium yosemitense (Yosemite onion) X X Anisocarpus scabridus (scabrid alpine tarplant) X X X Antennaria marginata (white-margined everlasting) X Antirrhinum subcordatum (dimorphic snapdragon) X Arabis rigidissima var. demota (Carson Range rock cress) X X Arctostaphylos cruzensis (Arroyo de la Cruz manzanita) X Arctostaphylos edmundsii (Little Sur manzanita) X Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. gabrielensis (San Gabriel manzanita) X X Arctostaphylos hooveri (Hoover's manzanita) X Arctostaphylos luciana (Santa Lucia manzanita) X Arctostaphylos nissenana (Nissenan manzanita) X X Arctostaphylos obispoensis (Bishop manzanita) X Arctostphylos parryana subsp. tumescens (interior manzanita) X X Arctostaphylos pilosula (Santa Margarita manzanita) X Arctostaphylos rainbowensis (rainbow manzanita) X Arctostaphylos refugioensis (Refugio manzanita) X Arenaria lanuginosa ssp. saxosa (rock sandwort) X Astragalus anxius (Ash Valley milk-vetch) X Astragalus bernardinus (San Bernardino milk-vetch) X Astragalus bicristatus (crested milk-vetch) X X Pacific Southwest Region, Regional Forester's Sensitive Species List. -

Stony Creek and Montecito Sequoia Resorts Biological Assessment And

Stony Creek and Montecito Sequoia Resorts Biological Assessment and Biological Evaluation for Sequoia National Forest Hume Lake Ranger District Improvement and Expansion Projects within Giant Sequoia National Monument Tulare County, California December 5, 2019 Prepared for: United States Forest Service Sequoia National Forest Hume Lake District District Ranger: Jeremy Dorsey 35860 East Kings Canyon Road Dunlap, CA 93621 Prepared by: Michelle McKenzie and Prairie Moore Natural Resources Management Corporation 1434 Third Street Eureka, CA 95501 Table of Contents I. Summary of Findings and Conclusions ........................................................................................ 1 II. Introduction, Background, and Project Understanding .............................................................. 2 Project Locations ......................................................................................................................... 3 Project Descriptions .................................................................................................................. 10 Biological Descriptions .............................................................................................................. 16 III. Methods ................................................................................................................................... 17 Pre-Field Review ........................................................................................................................ 17 Field Survey ..............................................................................................................................