Populationpressure and Migration: Implicationsfor Upland Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wage Order No.IVA-12 Final

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT National Wages and Productivity Commission Regional Tripartite Wages and Productivity Board No. IV-A City of Calamba, Laguna WAGE ORDER NO. IVA-12 SETTING THE MINIMUM WAGE FOR CALABARZON AREA WHEREAS, under R. A. 6727, Regional Tripartite Wages and Productivity Board –IVA (RTWPB- IVA) is mandated to rationalize minimum wage fixing in the Region based on various factors such as: the socio-economic condition affecting the cost of living of the workers, the business environment for the creation of new jobs and the preservation of existing employment, the capacity to pay by the majority of the employers, and the comparability of wages that will allow sustainable viability and competitiveness of business and industry; WHEREAS, the Board issues this Wage Order No. IVA-12, granting increases in the basic pay of all covered private sector workers in the region effective fifteen (15) days upon publication in a newspaper of general circulation; WHEREAS, the Board, as part of its regular functions made an assessment of the socio-economic indicators in the region and resolved to review the present wage structure of the region motu proprio; WHEREAS, the Board, in the performance of its mandate, engaged its clientele and stakeholders in the region to a series of consultations on the wage adjustment issue on June 6 and 22, 2007, July 3, 5, 12 and 19, 2007 and a public hearing on August 7, 2007 specifically, the locators in selected economic zones, the garments industry, the labor sector, -

The Land of Heroes and Festivities Calabarzon

Calabarzon The land of heroes and festivities is an acronym for the provinces comprising Getting There the region – CAvite, LAguna, BAtangas, Rizal Travelers can take air-conditioned buses going to southern and QueZON. It is situated immediately Luzon from among the multitudes of bus terminals within Calabarzon Metro Manila. Travel time to Cavite and Rizal usually takes south and east of Metro Manila, and is the an hour while Batangas, Laguna and Quezon may be complementary hideaway for anyone reached within two to four hours. looking to escape the hustle and bustle of Hotels and Resorts the capital. The region has a good collection of accommodation facilities that offer rest and recreation at stunningly-low Calabarzon is rich with stories relating to prices. From classy deluxe resort hotels to rental apartment options, one will find rooms, apartments and evens the country’s colonial past, of heroes and mansions that are suitable for every group of any size. revolutionaries standing up for the ideals of Spa resorts in Laguna and elsewhere are particularly popular, as individual homes with private springs are freedom and self-rule. Many monuments offered for day use, or longer. still stand as powerful reminders of days Sports Activities and Exploration gone by, but the region hurtles on as one of The region is blessed with an extensive selection the most economically-progressive areas of sport-related activities, such as golf in world-class for tourism, investments and trade. championship courses in Cavite, or volcano-trekking around Taal Lake, or diving off the magnificent coasts and Its future is bright and the way clear, thanks islands of Batangas, among others. -

Detailed Species Accounts from The

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

2018 Calabarzon Regional Development Report

2018 CALABARZON REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT REPORT Foreword HON. HERMILANDO I. MANDANAS RDC Chairperson The Calabarzon Regional Development Report (RDR) tracks the region’s socio-economic performance against the targets of the Calabarzon Regional Development Plan 2017-2022. This report highlights the role of government policies, programs and projects in meeting the development targets and outcomes in the Results Matrices of the RDP. Taking off from the assessment of the performance of the different sectors, the RDR also includes a spatial perspective on development across the region to improve targeting of interventions where it is most needed or suitable. We recognize not just the contributions made by national government agencies, regional line agencies, state universities and colleges, local government units but also civil society organizations in achieving our region’s vision to be a highly liveable and globally competitive industrial region. Our concerted effort is necessary to make our vision become a reality. The RDR, as an important input in carrying out the RDC’s functions on policy formulation and investment programming, is worth emphasizing. The 2018 RDR should guide all of us in the public and private sector in continuously delivering quality goods and services to the public and working together towards achieving AmBisyon Natin 2040 for a Matatag, Maginhawa, at Panatag na buhay para sa lahat ng Pilipino. 2018 Regional Development Report i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Foreword i Table of Contents ii List of Tables iv List of Figures -

Local Franchise

Republic of the Philippines ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION FOR AUTHORITY TO INCLUDE IN CUSTOMER'S BILL A TAX RECOVERY ADJUSTMENT CLAUSE (TRAC) FOR FRANCHISE TAXES PAID IN THE PROVINCE OF LAGUNA AND BUSINESS TAX PAID IN THE MUNICIPALITIES OF PANGIL, LUMBAN,PAGSANJAN AND PAKIL ALL IN THE PROVINCE OF LAGUNA ERC CASE NO. 2013-002 CF FIRST ,LAGUNA ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC. (FLECO), Applicant. x- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - x DECISION Before this Commission for resolution is the application filed on January 8, 2013 by the First Laguna Electric Cooperative, Inc, (FLECO) for authority to include in its customer's bill a Tax Recovery Adjustment Clause (TRAC) for franchise taxes paid to the Province of Laguna and business taxes paid to the Municipalities of Pangil, Lumban, Pagsanjan and Pakil, all in the Province of Laguna. In the said application, FLECO alleged, among others, that: 1. It is a non-stock non-profit electric cooperative (EC) duly organized and existing under and by virtue of the laws of the Republic of the Philippines. It is represented by its Board President, Mr. Gabriel C. Adefuin, It has its principal office at Barangay Lewin, Lumban, Laguna; " ERC CASE NO. 2013-002 CF DECISION/April 28, 2014 Page 2 of 18 2. It is the exclusive holder of a franchise issued by the National Electrification Administration (NEA) to operate an electric light and power services in the Municipalities of Cavinti, Pagsanjan, Lumban, Kalayaan, Paete, Pakil, Pangil, Siniloan, Famy, Mabitac, and Sta. Maria, all in the Province of Laguna; 3. -

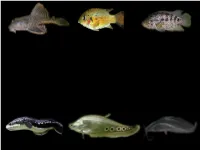

Existence of Invasive Species and Its Effect on Fishcages in Selected Municipality of Eastern Laguna Introduction

EXISTENCE OF INVASIVE SPECIES AND ITS EFFECT ON FISHCAGES IN SELECTED MUNICIPALITY OF EASTERN LAGUNA INTRODUCTION • Philippines have a long history in the field of aquaculture, which involves different kinds of farming practices of different varieties of fish species in a diverse ecosystem. It contributes significantly to the country’s food security, employment and foreign exchange earnings. However in some past few years aquaculture experience a decline on its production and it was subjected on different problem which had been faced. Some of the recent studies focused on the impacts of invasive species on the field of aquaculture especially on fish pen and fish cages. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY • IAS is among the top drivers of environmental change globally, and is known to threaten food security, human health and economic development. (Vitousek et al 1997) In the Philippines, data on the impact of IAS and to a number of anecdotal reports indicate that native species may be adversely affected through competition, predation, habitat alteration, and parasitism. Theoretical Framework of the study • This study adopts the theory of Evolution by Natural Selection of Charles Darwin. Conceptual framework The figure shows the interrelatedness of the variables. The first box which is the independent variable includes the different invasive organisms. The second box at the right side of the framework which is the dependent variable shows the production of some fish cage in Siniloan and Pakil Laguna. Independent Variable Dependent Variable Invasive Species Janitor Fish Gloria Production of Fish cages Jaguar Guapote GiantSnake Head Knife Fish Walking Catfish Objectives of the study • The study aimed to determine the existence of invasive species and its effect on fish cages in selected municipality of Eastern Laguna. -

PNB Foreclosed Properties in Laguna

Ver. 04.14.2015 ITEM SA9 - Lot Only Title ID : 20226 Lot Area: 2,405.00 sqm. TCT # 060-2013023848 Lot 43-B Magsaysay Road Brgy., San Antonio, San Pedro Laguna ITEM SA1 - School Min. Bid Price : 7,600,000.00 Title ID : Various Lot Area: 1,961.00 sqm. ITEM SA10 - House and Lot Floor Area: 1,384.50 sqm. Title ID : 20904 TCT # T-479813 TO T-479823 Lot Area: 217.00 sqm. Lot 2 To 12 Blk.21 Calamba Hills LAGUNA PROVINCE Floor Area: 378.00 sqm. Subdivision Phase 2 Brgy., TCT # T-695833 Properties for bidding Barandal Calamba. Laguna Title ID : 2917 Lot 23 B11 #13 Sapphire St. Min. Bid Price : 17,000,000.00 Lot Area: 638.00 sqm. Phase 1-A, Pacita Complex I, TCT # T-369841 / 2 Brgy., San Vicente, San Pedro Lot 11A & 11B, J.P. Rizal St., ITEM SA2 - School Laguna Poblacion, Calamba, Laguna Title ID : Various Min. Bid Price : 5,700,000.00 Min. Bid Price : 7,656,000.00 Lot Area: 2,116.00 sqm. Floor Area: 255.00 sqm. ITEM SA11 - Poultry/ Livestock TCT # T-479824 to T-479827 ITEM SA6 - Vacant Lot Title ID : 18685 Lot Nos. 1 To 4 Jardin Leonila Title ID : 11926 / 11925 Lot Area: 4,772.00 sqm. Subdivision Barangay Maahas, Lot Area: 6,689.00 sqm. Floor Area: 424.00 sqm. April 29, 2015 Los Baños Laguna TCT # T-292426 / T-292427 TCT # 058-2011002753 to 55 & Wednesday • 2:00 PM Min. Bid Price : 13,000,000.00 Lot 270 & 453 Halcon Street 58 Brgy., Palingon Calamba City, Lot Nos. -

PRIVATE SECTOR INITIATED POWER PROJECTS (LUZON) INDICATIVE As of 31 October 2020

PRIVATE SECTOR INITIATED POWER PROJECTS (LUZON) INDICATIVE As of 31 October 2020 Committed / Rated Capacity Target Testing & Name of the Project Project Proponent Location Project Status Target Commercial Operation Indicative (MW) Commissioning COAL 6,520 FEASIBILITY STUDY Pre-Engineering activities in progress 'PERMITS AND OTHER REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS: U1: Dec 2021 U1: Mar 2022 • Issued with GIS on 12 January 2015 (DOE-EPIMB SIS No. 2015-01-005) U2: Mar 2022 U2: June 2022 Indicative SMC Mariveles Coal-Fired Power Plant SMC Global Power Holdings Corp. Mariveles, Bataan 1,200 • MGCP ISSUED A NOTICE FOR SUSPENSION OF WORKS SINCE DECEMBER 13, 2016. U3: Sept 2022 U3: Dec 2022 • MGCP LIFTED THE SUSPENSION OF WORKS ON MAY 1, 2018. U4: Dec 2022 U4: Mar 2023 • OVERALL PROJECT CONSTRUCTION ACCOMPLISHMENT (AS OF JULY 2020) : 6% FEASIBILITY STUDY: • Pre-feasibility studies have conducted to determine the viability of the project- Completed in 2014 • Feasibility study "Draft Final Report" is expected to be completed in the 4th Quarter of 2019. ARRANGEMENT FOR SECURING THE REQUIRED LAND: • Land already secured and subject lots are undergoing titling. MARKETING OF GENERATING CAPACITIES: • On-going negotiations with MERALCO and Electric Cooperatives will be held on 3rd week of March • H&WB submitted the revised PSA Term Sheet to MERALCO that considers the latters inputs Dec. 12, 2017 Unit 1 - 2023 Unit 1 - 2023 Unit 2 -subject to the Unit 2 -subject to the PERMITS AND OTHER REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS: completion of the proposed completion of the proposed -

Region III Region IV-A

Shelter Cluster 3W PHILIPPINES: Humanitarian Response e as of 17 February 2010 Region Province Municipality Organization III-Central Luzon BULACAN SAN JOSE DEL MONTE Homeless Peoples Habitat for Humanity Legend AURORA PNRC / IFRC IV-A-Calarabazon LAGUNA BAY IOM Shelter Cluster Activities BINAN NHA PNRC / IFRC e Emergency Shelter Kit CALAMBA CITY IOM e Permanent Housing Swiss Embassy CITY OF SANTA ROSA NHA e Shelter Repair Kit LUMBAN IOM e Shelter Training-Assistance MABITAC IOM PAETE IOM e Tarpaulins PAGSANJAN IOM e Tents PAKIL IOM PANGIL IOM e Transitional Shelter Support 15°N PILA IOM 15°N e Transitory Housing Loan SANTA CRUZ IOM BULACAN SINILOAN IOM Region VICTORIA IOM RIZAL ANGONO Handicap International Province BINANGONAN IOM Municipality where activities conducted PILILIA IOM RODRIGUEZ (MONTALBAN) NHA SAN MATEO Handicap International TANAY Handicap International ORGANIZATIONS OXFAM Region III TAYTAY NHA Habitat for Humanity TERESA IOM Handicap International Habitat for Humanity Homeless Peoples PNRC / IFRC NCR-National Capital Region MARIKINA CITY Habitat for Humanity IOM – International Organization for NHA Migration MUNTINLUPA CITY IOM NHA – National Housing Authority e e PASIG CITY Habitat for Humanity OXFAM NHA PNRC – Philippine National Red Cross QUEZON CITY Habitat for Humanity SAN JOSE DEL MONTE IFRC – International Federation of the Red NHA Cross Homeless Peoples QUEZON Shelterbox e RODRIGUEZ (MONTALBAN) Swiss Embassy e e e SAN MATEO QUEZON CITY Map Doc Name: PHL-OCHA-00xx-3W_Shelter_Reg3_ e 4A_17Feb2010.mxd e e NCR Creation Date: 17 February 2010 MARIKINA CITY Projection/Datum: UTM/Luzon Datum Web Resources:http://www.un.org.ph/ response/ e RIZAL e Best printed at A3 paper size e Scale 1:300,000 e PASIG CITY TANAY e 02 4 8 Kilometers e TERESA TAYTAY e e e ANGONOe Data sources: e NSCB - (www.nscb.gov.ph). -

The Current State of Aquaculture in Laguna De Bay

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Israel, Danilo C. Working Paper The Current State of Aquaculture in Laguna de Bay PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2007-20 Provided in Cooperation with: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Philippines Suggested Citation: Israel, Danilo C. (2007) : The Current State of Aquaculture in Laguna de Bay, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2007-20, Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Makati City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127958 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas The Current State of Aquaculture in Laguna de Bay Danilo C. -

The Philippine Synthesis Report

Ecosystems and People The Philippine Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) Sub-Global Assessment Ecosystems and People: The Philippine Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) Sub-global Assessment Edited by Rodel D. Lasco Ma. Victoria O. Espaldon University of the Philippines Los Baños/ University of the Philippines World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF-Philippines) Diliman Editorial Assistant Maricel A. Tapia A contribution to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment prepared by the Philippine Sub-global Assessment Published by: Environmental Forestry Programme College of Forestry and Natural Resources University of the Philippines Los Baños In collaboration with: Department of Environment Laguna Lake and Natural Resources Development Authority Published by the Environmental Forestry Programme College of Forestry and Natural Resources University of the Philippines Los Baños College, Laguna, Philippines 4031 © Copyright 2005 by College of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of the Philippines Los Baños ISBN 971-547-237-0 Layout and cover design: Maricel A. Tapia This report is a contribution to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment prepared by the Philippine Sub-global Assessment Team. The report has been prepared and reviewed through a process approved by the MA Board but the report itself has not been accepted or approved by the Assessment Panel or the MA Board. CONTENTS Foreword vii Acknowledgments ix Summary for Decision Makers 1 Philippine Sub-Global Assessment: Synthesis 9 Introduction 35 Laguna Lake: Conditions and Trends 1. Overview of the Laguna Lake Basin 43 2. Laguna Lake’s Tributary River Watersheds 53 3. Water Resources 63 4. Fish 115 5. Rice 133 6. Biodiversity 151 7. Climate Change 167 8. Institutional Arrangements, Social Conflicts, and Ecosystem Trends 187 9. -

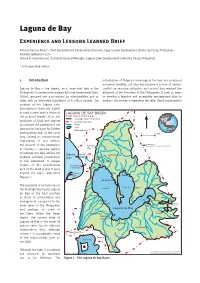

Laguna De Bay Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

Laguna de Bay Experience and Lessons Learned Brief Adelina Santos-Borja*, Chief, Research and Development Division, Laguna Lake Development Authority, Pasig, Philippines, [email protected] Dolora N. Nepomuceno, Assistant General Manager, Laguna Lake Development Authority, Pasig, Philippines * Corresponding author 1. Introduction introduction of fi shpen technology in the lake has produced economic benefi ts, but also has become a source of serious Laguna de Bay is the largest, most important lake in the confl ict on resource utilization and access that reached the Philippines. Its watershed contains 66 Local Government Units attention of the President of the Philippines. It took 15 years (LGUs), grouped into 5 provinces, 49 municipalities and 12 to develop a feasible and acceptable management plan to cities with an estimated population of 6 million people. The address the concerns regarding the lake. Rapid urbanization creation of the Laguna Lake Development Authority (LLDA) in 1966 started with a vision of /$*81$'(%$<%$6,1 1 the political leaders from the 7+(3+,/,33,1(6 'UDLQDJH%DVLQ%RXQGDU\ provinces of Rizal and Laguna //'$-XULVGLFWLRQ to cultivate the potential of the 5LYHU lake and its environs for further /DNH 6HOHFWHG&LW\ development and, at the same NP time, control its environmental degradation. It also refl ects -XULVGLFWLRQRI the wisdom of the lawmakers 4XH]RQ /DJXQD/DNH'HYHORSPHQW$XWKRULW\ in creating a separate agency &LW\ 0DULNLQD5 to manage the lake amidst the 0DQLOD 0DQLOD $QWLSROR&LW\ multiple political jurisdictions %D\ 3DVLJ &LW\ in the watershed. A unique 7D\WD\ 5 3DVLJ5 J Q feature of the jurisdictional $UHDZLWKLQWKLV R U DUHDLVRXWVLGH R area of the LLDA is that it goes //'$MXULVGLFWLRQ 0 beyond the lake’s watershed &DYLWH 7DQD\ (Figure 1).