Pat Quilter – Authentic Sound Reinforcement and Solid State Amp Guru by John Seetoo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

10/11 ANNUAL REPORT 10499_TouchNZ_AR_2011_FA.indd i 21/09/11 8:29 AM Cover and this page photography by Capture the Event (www.capturetheevent.com) All other photography by Auckland Sports Photography (www.aucklandsportsphotography.com) 10499_TouchNZ_AR_2011_FA.indd ii 21/09/11 8:29 AM CONTENTS Member Associations of Touch New Zealand 2 Touch New Zealand Offi cials 2010–2011 3 President’s Message 4 Chair’s Report 6 CEO’s Report 8 Marketing Report 10 Junior Development Report 18 National Coaching Report 21 Total Touch Report 24 Referees Report 32 Touch NZ Membership Statistics 2010-2011 35 Financial Statements 40 Notes to the Accounts 46 Auditor’s Report 52 TOUCH NEW ZEALAND ANNUAL REPORT 2010/2011 | 1 10499_TouchNZ_AR_2011_FA.indd 1 21/09/11 8:29 AM MEMBER ASSOCIATIONS OF TOUCH NEW ZEALAND Auckland Touch Association Bay of Plenty Touch Association Touch Canterbury Counties Manukau Touch Association Touch Hawkes Bay Touch Kapiti Horowhenua Marlborough Touch Association Manawatu Touch Association Nelsons Bay Touch Association Touch North Harbour Otago Touch Association Taranaki Touch Te Tairawhiti Touch Te Tai Tokerau Touch Touch Southland Thames Valley Touch Association Touch Wanganui Waikato Touch Association Wellington Touch Association 2 | TOUCH NEW ZEALAND ANNUAL REPORT 2010/2011 10499_TouchNZ_AR_2011_FA.indd 2 21/09/11 8:29 AM TOUCH NEW ZEALAND OFFICIALS EXPIRY DATE PRESIDENT John Watson 2011 AGM TOUCH NEW ZEALAND BOARD Steve Wilkinson 2013 AGM (Chair) Darrin Sykes 2011 AGM (deputy Chair) Nigel Georgieff 2012 AGM Simon Buttery 2011 -

A History of Sampling

Organised Sound http://journals.cambridge.org/OSO Additional services for Organised Sound: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here A history of sampling HUGH DAVIES Organised Sound / Volume 1 / Issue 01 / April 1996, pp 3 - 11 DOI: null, Published online: 08 September 2000 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S135577189600012X How to cite this article: HUGH DAVIES (1996). A history of sampling. Organised Sound, 1, pp 3-11 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/OSO, IP address: 128.59.222.12 on 11 May 2014 TUTORIAL ARTICLE A history of sampling HUGH DAVIES 25 Albert Road, London N4 3RR Since the mid-1980s commercial digital samplers have At the end of the 1980s other digital methods of become widespread. The idea of musical instruments which solving some of the problems inherent in high quality have no sounds of their own is, however, much older, not PCM began to be explored. In ®gure 1(b) pulse-ampli- just in the form of analogue samplers like the Mellotron, tude is shown as a vertical measurement in which but in ancient myths and legends from China and elsewhere. information is encoded as the relative height of each This history of both digital and analogue samplers relates successive regular pulse. The remaining possibilities the latter to the early musique concreÁte of Pierre Schaeffer and others, and also describes a variety of one-off systems are horizontal, such as a string of coded numerical devised by composers and performers. values for PCM, and the relative widths (lengths) of otherwise identical pulses and their density (the spac- ing between them). -

Optical Turntable As an Interface for Musical Performance

Optical Turntable as an Interface for Musical Performance Nikita Pashenkov A.B. Architecture & Urban Planning Princeton University, June 1998 Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2002 @ Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 2 7 2002 LIBRARIES ROTCH I|I Author: Nikita Pashenkov Program in Media Arts and Sciences May 24, 2002 Certified by: John Maeda Associate Professor of Design and Computation Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Dr. Andew B. Lippman Chair, Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies Program | w | in Media Arts and Sciences Optical Turntable as an Interface for Musical Performance Nikita Pashenkov Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, on May 24, 2002, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Media Arts and Sciences Abstract This thesis proposes a model of creative activity on the computer incorporating the elements of programming, graphics, sound generation, and physical interaction. An interface for manipulating these elements is suggested, based on the concept of a disk-jockey turntable as a performance instrument. A system is developed around this idea, enabling optical pickup of visual informa- tion from physical media as input to processes on the computer. Software architecture(s) are discussed and examples are implemented, illustrating the potential uses of the interface for the purpose of creative expression in the virtual domain. -

Lity; Price Willplease Bshing

f?y?Te Star Wind Mills. Charter Used If you do'aot want Gasoline Engine, what do of a WindmillT I am sure Stationarles, Portables, Go- - you think that yon can't do better than to buy a STAR. Lots in use Gasoline uvm. around here, and all satisfactory. Vntrlrtt State Your Power Needs or; Your Customers' Needs. Bee. engine. E. N. Ct. E. N SIPPERLEY, ... Wbbtport, Conn. lie Newtown Sipperley, Westport, VOLUME XXV. NEWTOWN, CONN., FRIDAY, APRIL 18, 1902. TEN PAGES. NUMBER 16. 'Dry feet are essential to good health." LOCAL AFFAIRS. Rubbers LET US DRESS THE CON QREGATION AL CHURCH Will keep your feet dry. A FELLOWSHIP MEETING. Your Boy. At the Fellowship meeting, to be Foster's held la the Congregational church on Tuesday, April 29, this is the program, Is the to buy good rubbers. We as now place Glove-Fittin- well so far it can be given: sell the well known GOODYEAR g We will make him look as as you want; Rubbers and Boots. the clothes and furnishings and hat will be all MORNING SESSION. C. W. Brooktteld Cen- High-to- p boots just the thing for trout in the Rev Francis, made they ought to be quality; price willplease Bshing. The best see the new ter, presiding. you. Will you come and Spring 10.30. Devotional Service, led by W. ? ' boy-clothe- s E. Mitchell, South Britain. R S In place of Vestee suits come Norfolks, grace- 10.45. Brief reports from the church- FOS TE ful, becoming, loose and comfortable for the boy. -

NEW ZEALAND ASIA INSTITUTE Te Roopu Aotearoa Ahia Annual

Level 6, 12 Grafton Road Private Bag 92019 Auckland, New Zealand Tel: (64 9) 373 7599 Fax: (64 9) 208 2312 Email: [email protected] NEW ZEALAND ASIA INSTITUTE Te Roopu Aotearoa Ahia Annual Report 2011 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgements 1. Overview 2. Highlights 3. Program of Activities 4. NZAI Offshore 5. Personnel 6. Financial Report 7. Publications 8. Conclusion 2 The New Zealand Asia Institute seeks to develop graduates, knowledge and ideas that enhance New Zealand‟s understanding of, and ability to engage productively with, Asia. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The New Zealand Asia Institute (NZAI) acknowledges with gratitude the generous financial support from the Japan Foundation, the Chiang Chin-Kuo Foundation, the Korea Foundation, the Institute of International Relations at the National Chengchi University in Taiwan, Malcolm Pacific Ltd, Numberwise Ltd, and Printing.com, without which the successful completion of the 2011 research projects would not have been possible. The Institute would also like to thank the following institutional collaborators for their cooperation and support for the activities of the Institute in 2011: Japanese Consulate- General in Auckland, the New Zealand Contemporary China Research Centre at the Victoria University of Wellington, Auckland University of Technology Australian National University, Chinese University of Hong Kong, National Chengchi University, National Cheng Kung University, Chiangmai University, China Institute of Contemporary International Relations, Copenhagen Business School, De La Salle University -

Monday May 16

The Press, Christchurch May 10, 2011 15 MONDAY MAY 16 Electric Dreams CSI: Crime Scene Investigation Top Chef Bunny and theBull 7.30pm, Prime 8.30pm, TV3 8.30pm, Four 8.30pm, Rialto ★★★ On tonight’s second episode of Pop star Justin Bieber returns as For the first time in Top Chef’s From the creators of The Mighty this excellent BBC reality series, distressed teen Jason McCann on eight-year history, this week sees Boosh comes this 2009 UK comedy the Sullivan-Barnes family head tonight’s episode. Meanwhile, head judge Tom Colicchio about a young shut-in who takes back to the 1980s. As well as Langston (Laurence Fishburne) stepping into the kitchen and an imaginary road trip inside his attempting to cook a roast dinner testifies against his nemesis Nate challenging the chefs to top his apartment, based on mementos in a microwave oven, they also Haskell, and Nick (George Eads) time in creating a dish for the and memories of a European trek have to navigate home computers is warned that he is in danger, but quickfire challenge. Then, for the from years before. ‘‘Tamps down and complete the arduous task of cannot tell him who or why elimination challenge, the chefs its whimsy with a rich vein of finding a rental shop that still without putting himself in even head to Chinatown and work as a very silly, very British comedy,’’ supplies films on video cassette more danger. team to serve dim sum for the wrote Empire magazine’s Nick de for their new VHS player. -

Resenv Research Update 4/16 Joe Paradiso an Introduction to Prog Rock Prof

ResEnv Research Update 4/16 Joe Paradiso An Introduction to Prog Rock Prof. J. Paradiso – MIT Media Lab Session 1: Intro - Things your dad should have told you about Prog Session 2; Canterbury Session 3: Rock in Opposition Session 4: Zeuhl Session 5: Space Rock and Neopsychedelia Session 6: French & Quebecois Prog Session 7: Rock Progressivo Italiano Session 8: Germany, Berlin, and Krautrock (perhaps some Scandavania too) Session 9: Japanese Prog Lecture 1 – Introduction, Roots of Prog, Classic Prog ResEnv Research Update 4/16 Joe Paradiso 1/10/2018 IAP 2018 Books on Prog…. And books on many bands – e.g., Soft Machine, Hawkwind… 4/08 JAP Resources ‘Romantic Warriors’ DVD set by Adele Schmidt & José Zegarra Holder In MIT’s Music Library Krautrock documentary in progress – Italian prog and perhaps space rock, etc. coming…. 4 4/08 JAP Magazines In Lewis Music Library! 5 4/08 JAP Some Websites & Resources http://www.progarchives.com http://www.proggnosis.com http://www.expose.org Chris Cutler’s Podcasts: http://ccutler.co.uk/ccpodcast.htm Many Facebook Groups: Avant Progressive, Canterbury, etc., etc. 7 4/08 JAP Vendors… http://synphonicmusic.com/ https://www.lasercd.com/ http://www.waysidemusic.com 7 More Vendors (UK) http://home.btconnect.com/ultimathule/index.html https://burningshed.com/ http://www.rermegacorp.com/ http://www.progrock.co.uk/ Prog Festivals! https://burgherzberg-festival.de/ http://rockinopposition.rocktime.org/ https://www.progday.net/ https://proglodytes.com/2017/12/07/exhaustive-prog-festival-list-2018/ http://www.gaudela.net/gar/ 4/08 JAP A Historical Perspective 10 ~14K Albums – most on CD! 4/08 JAP Music <> Exploration - I seek out music everywhere! 12 4/08 JAP • WMFO, WMBR, WZBC Radio Shows • 1974 – 1994 • Still sporadically – e.g. -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality. -

DB-1981-05.Pdf

INTRODUCING THE HOTTEST NEW INTERNATIONAL RECORDING STAR. r r r 2' t I. IT .. ,..,,, 32- Channel Xó Digital Recorder It wont be long before the charts are as big a sound breakthrough as stereo will allow for extremely precise and filled with tracks recorded on the new was to the industry Digital Audio Disc flexible electronic editing, and an Mitsubishi X800 32- channel digital players for the home are already a attractive enhancement of the razor audio recorders. And why not. The reality in Japan and are going to be blade editing capability of our X80 Mitsubishi X800 doesn't just record available here nex: year..The con- Series recorders. an artist's sound -it captures it. Every sumers and recording artists will be We have a full line of digital subtle lick. Every gentle nuance. It demanding digital sound. Will your products for you now and we intend records it in a way that makes the studio be ready? to keep exploring this new dimension listener feel like he's right in the booth in sound to meet your changing needs. with the players. WHY INSIST ON MITSUBISHI? When you record on the Mitsubishi The X800 digital audio recordings Because we pioneered the digital X800 and master on the X80 Series are not subject to the limitations of recording effort back in the early recorders. your final product will be a analog recordings. There's no tape seventies. Since then we have been whole new experience in sound. hiss. No print- through. No dropout refining and perfecting our equipment errors. -

![IK Multimedia Sampletron]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0416/ik-multimedia-sampletron-3320416.webp)

IK Multimedia Sampletron]

p 56 Test[ IK Multimedia SampleTron] CD Track 04 Software-Instrument für Mac und PC IK Multimedia SampleTron Im Moment steht die Soundästhetik der späten Sechziger- und frühen Siebzigerjahre bei vielen Produzenten und aktuellen Bands wie z. B. MGMT wieder hoch im Kurs. Daher kommt eine Software wie SampleTron genau zur rechten Zeit. SampleTron ist ein virtuelles Instrument Unter den 17 Instrumenten, die in zehnjäh- hören z. B. auf Bowies „Space Oddity”) und von IK Multimedia, das mit Samples legen- riger Arbeit gesampelt wurden, sind auch des Roland-Vocoders VP-330. därer Vintage-Keyboards und Sampler-Vor- zwei ziemlich exotische Rhythmusmaschinen SampleTron basiert auf der bewährten gänger wie dem Mellotron und seinen Ver- (Mellotron Powerhouse und Chamberlin SampleTank-2-Engine, die viele Features zur wandten ausgestattet ist. IK nennt diese Rhythmate), die mit Tapeloops arbeiten. Mit Nachbearbeitung bietet, und steht stand- Instrumentenfamilie „Tron-Instruments”. dem Digital Keyboard von 360 Systems ist alone sowie als Plug-in für die VST-, AU- Ein Großteil dieser meist sehr anfälligen und außerdem ein frühes digitales Instrument da- und RTAS-Schnittstellen für PC (XP / Vista) wartungsintensiven Dinosaurier arbeitet wie bei, das 8-Bit-Samples bietet. Einige Instru- und Mac (OS X, Universal Binary) zur Ver- das Mellotron mit Tonbändern, welche die mente arbeiten mit geloopten Sounds, die auf fügung. Das 56-fach polyfone Plug-in ist 16- Sounds auf Tastendruck abspielen. Dazu ge- Flexidics abgespielt werden. Zu dieser Gruppe fach multitimbral, und die Sounds lassen hören außer den Mellotron-Modellen M400, gehört das Optigan von Mattel (siehe Love sich auf ebenso viele Stereoausgänge routen. MK5 und MKII auch das Vako Orchestron, The Machines, S&R 04/2008), der Chilton Layer und Split-Operationen werden durch das Novatron (das dem Mellotron M400 Talent Maker und das Vako Orchestron. -

Kraftwerk's Influence on Music Technology & German Cultural

1 Through the Looking Glass: Kraftwerk’s Influence on Music Technology & German Cultural Identity Scott Shannon University of Houston, Texas, USA [email protected] Kyle J. Messick Ivy Tech Community College, Indiana, USA [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0452-0922 2 Through the Looking Glass: Kraftwerk’s Influence on Music Technology & German Cultural Identity Although the band Kraftwerk have been extensively noted for their pioneering musical style, what has been given less attention is their broader cultural impact, how they served as a source for German identity in a time of crisis, and the conditions under which their music was formed and changed over time. This article examines their influence through the sense of cultural identity Kraftwerk provided for Germanic peoples post-World War II, their fundamental influence on future musical acts that would incorporate electronics into their music, their innovation in their creation of new musical instruments/technologies, and the application of those instruments in novel performance and recording settings. Keywords: Kraftwerk, krautrock, music technology, Germanic culture, identity The Emergence of Kraftwerk & Krautrock During the 1960’s and 1970’s, popular music as a whole experienced an explosion of growth and diversification. With the developments of the progressive rock and industrial scenes in the UK, the jazz fusion scene in the US, and the krautrock/“Berlin School” scenes in Germany, music was undergoing a complete cosmopolitan renaissance heavily rooted in sonic experimentation and pushing musical boundaries in a way that had never been witnessed before. “Krautrock” was the colloquial term used to describe the experimental rock that developed in West Germany in the late 1960s that combined elements of psychedelic rock, electronic music, and a broad range of avant-garde influences. -

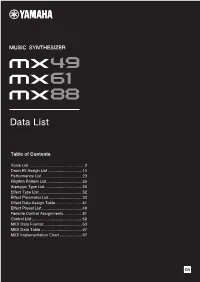

MX49 MX61 MX88 Data List 2 Voice List

Data List Table of Contents Voice List..................................................2 Drum Kit Assign List ...............................10 Performance List ....................................23 Rhythm Pattern List................................25 Arpeggio Type List .................................26 Effect Type List.......................................32 Effect Parameter List..............................33 Effect Data Assign Table........................41 Effect Preset List ....................................49 Remote Control Assignments.................51 Control List .............................................52 MIDI Data Format...................................53 MIDI Data Table .....................................57 MIDI Implementation Chart ....................67 EN Voice List Category Category Category Category Number Voice Name MSB LSB PC Polyphony Number Voice Name MSB LSB PC Polyphony (Main) (Sub) (Main) (Sub) AP APno 001 CncrtGrand 63 0 1 2 KB FM 049 DX5-Zero 63 0 62 3 002 MelloGrand 63 0 3 2 050 E.Piano 2 0 0 6 2 003 Glasgow 63 0 4 2 Clavi 051 Vintg Clav 63 0 73 2 004 RmntcPiano 63 0 5 2 052 Super Clav 63 0 74 1 005 Mono Grand 63 0 16 1 053 StereoClav 63 0 75 2 006 C GrandPno 0 0 1 2 054 HollowClav 63 0 76 1 007 Rock Piano 0 0 2 1 055 Nu Phasing 63 0 77 2 008 Honkytonk 0 0 4 4 056 Touch Clav 63 0 78 2 Layer 009 Ballad Key 63 0 10 4 057 Pulse Clav 63 0 79 1 010 80s Layer 63 0 11 3 058 Gtrsichord 63 0 80 2 011 BalladStck 63 0 12 2 059 Hipsichord 63 0 81 3 012 Piano Back 63 0 13 4 060 Harpsicord 0 0 7 1 013 P.&Strings