The Empirical Foundations of Calibration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960’

JOURNALOF Monetary ECONOMICS ELSEVIER Journal of Monetary Economics 34 (I 994) 5- 16 Review of Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz’s ‘A monetary history of the United States, 1867-1960’ Robert E. Lucas, Jr. Department qf Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA (Received October 1993; final version received December 1993) Key words: Monetary history; Monetary policy JEL classijcation: E5; B22 A contribution to monetary economics reviewed again after 30 years - quite an occasion! Keynes’s General Theory has certainly had reappraisals on many anniversaries, and perhaps Patinkin’s Money, Interest and Prices. I cannot think of any others. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s A Monetary History qf the United States has become a classic. People are even beginning to quote from it out of context in support of views entirely different from any advanced in the book, echoing the compliment - if that is what it is - so often paid to Keynes. Why do people still read and cite A Monetary History? One reason, certainly, is its beautiful time series on the money supply and its components, extended back to 1867, painstakingly documented and conveniently presented. Such a gift to the profession merits a long life, perhaps even immortality. But I think it is clear that A Monetary History is much more than a collection of useful time series. The book played an important - perhaps even decisive - role in the 1960s’ debates over stabilization policy between Keynesians and monetarists. It organ- ized nearly a century of U.S. macroeconomic evidence in a way that has had great influence on subsequent statistical and theoretical research. -

2005 Mincer Award

Mincer Award Winners 2005: Orley Ashenfelter is one of the two winners of the 2005 Society of Labor Economists’ Jacob Mincer prize honoring lifetime achievements in the field of labor economics. Over the course of a distinguished career, Orley Ashenfelter has had tremendous influence on the development of modern labor economics. His early work on trade unions brought neoclassical economics to bear on a subject that had been the domain of traditional institutionally-oriented industrial relations specialists. As labor supply emerged as one of the most important subjects in the new field, Ashenfelter showed (in work with James Heckman) that neoclassical theory could be applied to decision making within the family. In his Frisch-prize winning 1980 article, Ashenfelter developed a theoretical and empirical framework for distinguishing between voluntary and involuntary unemployment. Orley was also involved in the income maintenance experiments, the first large-scale social experiments. In 1972 Orley served as Director of the Office of Evaluation of the U.S. Dept. of Labor and became deeply interested in the problem of program evaluation. This focus led him to emphasize developing credible and transparent sources of identification through strategies such as the collection of new data, difference-in-difference designs, and exploiting “natural experiments.” In the 1990s, Orley turned to measuring the returns to education. In a series of studies using new data on twins, Ashenfelter (with Alan Kreuger and Cecilia Rouse) suggested that OLS estimates of the returns to schooling were biased downward to a significant degree. Orley has also had a significant impact on the development of empirical law and economics in recent years. -

Learning, Career Paths, and the Distribution of Wages†

American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2019, 11(1): 49–88 https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20170390 Learning, Career Paths, and the Distribution of Wages† By Santiago Caicedo, Robert E. Lucas Jr., and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg* We develop a theory of career paths and earnings where agents organize in production hierarchies. Agents climb these hierarchies as they learn stochastically from others. Earnings grow as agents acquire knowledge and occupy positions with more subordinates. We contrast these and other implications with US census data for the period 1990 to 2010, matching the Lorenz curve of earnings and the observed mean experience-earnings profiles. We show the increase in wage inequality over this period can be rationalized with a shift in the level of the complexity and profitability of technologies relative to the distribution of knowledge in the population. JEL D83, E24, J24, J31 ( ) his paper develops a new model of an economy that generates sustained pro- Tductivity growth. One distinctive feature of the model is that all knowledge in the economy is held by the individual people who comprise it: there is no abstract technology hovering above them in the ether. A second feature, necessarily involv- ing heterogeneous labor, is a kind of complementarity in production involving peo- ple with different skill levels: the marginal product of any one person is contingent on the people he works with. A third feature, closely related to the second, is that improvements over time in individual skill levels depend on imitation or stimulation or inspiration from other people in the economy. All growth is taken to arise from this force. -

Econ792 Reading 2020.Pdf

Economics 792: Labour Economics Provisional Outline, Spring 2020 This course will cover a number of topics in labour economics. Guidance on readings will be given in the lectures. There will be a number of problem sets throughout the course (where group work is encouraged), presentations, referee reports, and a research paper/proposal. These, together with class participation, will determine your final grade. The research paper will be optional. Students not submit- ting a paper will receive a lower grade. Small group work may be permitted on the research paper with the instructors approval, although all students must make substantive contributions to any paper. Labour Supply Facts Richard Blundell, Antoine Bozio, and Guy Laroque. Labor supply and the extensive margin. American Economic Review, 101(3):482–86, May 2011. Richard Blundell, Antoine Bozio, and Guy Laroque. Extensive and Intensive Margins of Labour Supply: Work and Working Hours in the US, the UK and France. Fiscal Studies, 34(1):1–29, 2013. Static Labour Supply Sören Blomquist and Whitney Newey. Nonparametric estimation with nonlinear budget sets. Econometrica, 70(6):2455–2480, 2002. Richard Blundell and Thomas Macurdy. Labor supply: A Review of Alternative Approaches. In Orley C. Ashenfelter and David Card, editors, Handbook of Labor Economics, volume 3, Part 1 of Handbook of Labor Economics, pages 1559–1695. Elsevier, 1999. Pierre A. Cahuc and André A. Zylberberg. Labor Economics. Mit Press, 2004. John F. Cogan. Fixed Costs and Labor Supply. Econometrica, 49(4):pp. 945–963, 1981. Jerry A. Hausman. The Econometrics of Nonlinear Budget Sets. Econometrica, 53(6):pp. 1255– 1282, 1985. -

Technical Paper Series Congressional Budget Office Washington, DC

Technical Paper Series Congressional Budget Office Washington, DC MODELING LONG-RUN ECONOMIC GROWTH Robert W. Arnold Congressional Budget Office Washington, D.C. 20515 [email protected] June 2003 2003-4 Technical papers in this series are preliminary and are circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment. These papers are not subject to CBO’s formal review and editing processes. The analysis and conclusions expressed in them are those of the author and should not be interpreted as those of the Congressional Budget Office. References in publications should be cleared with the author. Papers in this series can be obtained from www.cbo.gov. Abstract This paper reviews the recent empirical literature on long-run growth to determine what factors influence growth in total factor productivity (TFP) and whether there are any channels of influence that should be added to standard models of long-run growth. Factors affecting productivity fall into three general categories: physical capital, human capital, and innovation (including other factors that might influence TFP growth). Recent empirical evidence provides little support for the idea that there are extra-normal returns to physical capital accumulation, nor is there solid justification for adding a separate channel of influence from capital to TFP growth. The paper finds evidence that human capital—as distinct from labor hours worked—is an important factor for growth but also that there is not yet a consensus about exactly how it should enter the model. Some argue that human capital should enter as a factor of production, while others argue that it merely spurs innovation. The forces governing TFP growth are not well understood, but there is evidence that R&D spending is a significant contributor and that its benefit to society may exceed its benefit to the company doing the spending—that is, it is a source of spillovers. -

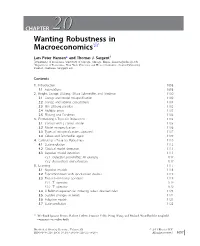

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$ Lars Peter Hansen* and Thomas J. Sargent{ * Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. [email protected] { Department of Economics, New York University and Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, California. [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 1098 1.1 Foundations 1098 2. Knight, Savage, Ellsberg, Gilboa-Schmeidler, and Friedman 1100 2.1 Savage and model misspecification 1100 2.2 Savage and rational expectations 1101 2.3 The Ellsberg paradox 1102 2.4 Multiple priors 1103 2.5 Ellsberg and Friedman 1104 3. Formalizing a Taste for Robustness 1105 3.1 Control with a correct model 1105 3.2 Model misspecification 1106 3.3 Types of misspecifications captured 1107 3.4 Gilboa and Schmeidler again 1109 4. Calibrating a Taste for Robustness 1110 4.1 State evolution 1112 4.2 Classical model detection 1113 4.3 Bayesian model detection 1113 4.3.1 Detection probabilities: An example 1114 4.3.2 Reservations and extensions 1117 5. Learning 1117 5.1 Bayesian models 1118 5.2 Experimentation with specification doubts 1119 5.3 Two risk-sensitivity operators 1119 5.3.1 T1 operator 1119 5.3.2 T2 operator 1120 5.4 A Bellman equation for inducing robust decision rules 1121 5.5 Sudden changes in beliefs 1122 5.6 Adaptive models 1123 5.7 State prediction 1125 $ We thank Ignacio Presno, Robert Tetlow, Franc¸ois Velde, Neng Wang, and Michael Woodford for insightful comments on earlier drafts. Handbook of Monetary Economics, Volume 3B # 2011 Elsevier B.V. ISSN 0169-7218, DOI: 10.1016/S0169-7218(11)03026-7 All rights reserved. -

Trygve Haavelmo, James J. Heckman, Daniel L. Mcfadden, Robert F

Trygve Haavelmo, James J. Heckman, Daniel L. McFadden, Robert F. Engle and Clive WJ. Granger Edited by Howard R. Vane Professor of Economics Liverpool John Moores University, UK and Chris Mulhearn Reader in Economics Liverpool John Moores University, UK PIONEERING PAPERS OF THE NOBEL MEMORIAL LAUREATES IN ECONOMICS An Elgar Reference Collection Cheltenham, UK • Northampton, MA, USA Contents Acknowledgements ix General Introduction Howard R. Vane and Chris Mulhearn xi PART I TRYGVE HAAVELMO Introduction to Part I: Trygve Haavelmo (1911-99) 3 1. Trygve Haavelmo (1943a), 'The Statistical Implications of a System of Simultaneous Equations', Econometrica, 11 (1), January, 1-12 7 2. Trygve Haavelmo (1943b), 'Statistical Testing of Business-Cycle Theories', Review of Economic Statistics, 25 (1), February, 13-18 19 3. Trygve Haavelmo (1944), 'The Probability Approach in Econometrics', Econometrica, 12, Supplement, July, iii-viii, 1-115 25 4. M.A. Girshick and Trygve Haavelmo (1947), 'Statistical Analysis of the Demand for Food: Examples of Simultaneous Estimation of Structural Equations', Econometrica, 15 (2), April, 79-110 146 PART II JAMES J. HECKMAN Introduction to Part II: James J. Heckman (b. 1944) 181 5. James Heckman (1974), 'Shadow Prices, Market Wages, and Labor Supply', Econometrica, 42 (4), July, 679-94 185 6. James J. Heckman (1976), 'A Life-Cycle Model of Earnings, Learning, and Consumption', Journal of Political Economy, 84 (4, Part 2), August, S11-S44, references 201 7. James J. Heckman (1979), 'Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error', Econometrica, 47 (1), January, 153-61 237 8. James Heckman (1990), 'Varieties of Selection Bias', American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 80 (2), May, 313-18 246 9. -

Professor Orley Ashenfelter Is the World's Leading Researcher in The

Citation read out at the Royal Society of Edinburgh on 24 March 2005 upon the election of Professor Orley Ashenfelter to the Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Professor Orley Ashenfelter is the Joseph Douglas Green 1895 Professor of Economics at Princeton University. He is the world's leading researcher in the field of labour economics, and has also made major contributions to research in the field of econometrics and law and economics. As Director of the Office of Evaluation of the US Department of Labour in 1972, Professor Ashenfelter began the work that is now widely recognized as the field of "quantitative social program evaluation." His influential work on the econometric evaluation of government retraining programs led to the systematic development of rigorous methods for the evaluation of many social programs. Professor Ashenfelter is also regarded as the originator of the use of so-called "natural experiments" to infer causality about economic relationships. This approach, now becoming universal in all the social sciences, is associated with Princeton University's Industrial Relations Section, of which Professor Ashenfelter was Director. He edited the Handbook of Labour Economics, and is currently Editor of the American Law and Economics Review. His current research includes the evaluation of the effect of schooling on earnings, the cross- country measurement of wage rates, and many other issues related to the economics of labour markets. His further interests include the market for fine wine. Several of his contributions to the economics research literature have been motivated by and reflect this interest. Professor Ashenfelter is a frequent visitor to the UK, and has been visiting Professor at the London School of Economics and the University of Bristol. -

1 Nobel Autobiography Angus Deaton, Princeton, February 2016 Scotland

Nobel Autobiography Angus Deaton, Princeton, February 2016 Scotland I was born in Edinburgh, in Scotland, a few days after the end of the Second World War. Both my parents had left school at a very young age, unwillingly in my father’s case. Yet both had deep effects on my education, my father influencing me toward measurement and mathematics, and my mother toward writing and history. The school in the Yorkshire mining village in which my father grew up in the 1920s and 1930s allowed only a few children to go to high school, and my father was not one of them. He spent much of his time as a young man repairing this deprivation, mostly at night school. In his village, teenagers could go to evening classes to learn basic surveying and measurement techniques that were useful in the mine. In Edinburgh, later, he went to technical school in the evening, caught up on high school, and after many years and much difficulty, qualified as a civil engineer. He was determined that I would have the advantages that he had been denied. My mother was the daughter of William Wood, who owned a small woodworking business in the town of Galashiels in the Scottish Borders. Although not well-educated, and less of an advocate for education than my father, she was a great story-teller (though it was sometimes hard to tell the stories from gossip), and a prodigious letter- writer. She was proud of being Scottish (I could make her angry by saying that I was British, and apoplectic by saying that I was English), and she loved the Borders, where her family had been builders and carpenters for many generations. -

Pricing Uncertainty Induced by Climate Change∗

Pricing Uncertainty Induced by Climate Change∗ Michael Barnett William Brock Lars Peter Hansen Arizona State University University of Wisconsin University of Chicago and University of Missouri January 30, 2020 Abstract Geophysicists examine and document the repercussions for the earth’s climate induced by alternative emission scenarios and model specifications. Using simplified approximations, they produce tractable characterizations of the associated uncer- tainty. Meanwhile, economists write highly stylized damage functions to speculate about how climate change alters macroeconomic and growth opportunities. How can we assess both climate and emissions impacts, as well as uncertainty in the broadest sense, in social decision-making? We provide a framework for answering this ques- tion by embracing recent decision theory and tools from asset pricing, and we apply this structure with its interacting components to a revealing quantitative illustration. (JEL D81, E61, G12, G18, Q51, Q54) ∗We thank James Franke, Elisabeth Moyer, and Michael Stein of RDCEP for the help they have given us on this paper. Comments, suggestions and encouragement from Harrison Hong and Jose Scheinkman are most appreciated. We gratefully acknowledge Diana Petrova and Grace Tsiang for their assistance in preparing this manuscript, Erik Chavez for his comments, and Jiaming Wang, John Wilson, Han Xu, and especially Jieyao Wang for computational assistance. More extensive results and python scripts are avail- able at http://github.com/lphansen/Climate. The Financial support for this project was provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation [grant G-2018-11113] and computational support was provided by the Research Computing Center at the University of Chicago. Send correspondence to Lars Peter Hansen, University of Chicago, 1126 E. -

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓ ΡΑΦΙΑ Bibliography

Τεύχος 53, Οκτώβριος-Δεκέμβριος 2019 | Issue 53, October-December 2019 ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓ ΡΑΦΙΑ Bibliography Βραβείο Νόμπελ στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη Nobel Prize in Economics Τα τεύχη δημοσιεύονται στον ιστοχώρο της All issues are published online at the Bank’s website Τράπεζας: address: https://www.bankofgreece.gr/trapeza/kepoe https://www.bankofgreece.gr/en/the- t/h-vivliothhkh-ths-tte/e-ekdoseis-kai- bank/culture/library/e-publications-and- anakoinwseis announcements Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος. Κέντρο Πολιτισμού, Bank of Greece. Centre for Culture, Research and Έρευνας και Τεκμηρίωσης, Τμήμα Documentation, Library Section Βιβλιοθήκης Ελ. Βενιζέλου 21, 102 50 Αθήνα, 21 El. Venizelos Ave., 102 50 Athens, [email protected] Τηλ. 210-3202446, [email protected], Tel. +30-210-3202446, 3202396, 3203129 3202396, 3203129 Βιβλιογραφία, τεύχος 53, Οκτ.-Δεκ. 2019, Bibliography, issue 53, Oct.-Dec. 2019, Nobel Prize Βραβείο Νόμπελ στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη in Economics Συντελεστές: Α. Ναδάλη, Ε. Σεμερτζάκη, Γ. Contributors: A. Nadali, E. Semertzaki, G. Tsouri Τσούρη Βιβλιογραφία, αρ.53 (Οκτ.-Δεκ. 2019), Βραβείο Nobel στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη 1 Bibliography, no. 53, (Oct.-Dec. 2019), Nobel Prize in Economics Πίνακας περιεχομένων Εισαγωγή / Introduction 6 2019: Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer 7 Μονογραφίες / Monographs ................................................................................................... 7 Δοκίμια Εργασίας / Working papers ...................................................................................... -

Hansen & Sargent 1980

Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 2 (1980) 7-46. 0 North-Holland FORMULATING AND ESTIMATING DYNAMIC LINEAR RATIONAL EXPECTATIONS MODELS* Lars Peter HANSEN Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA Thomas J. SARGENT University of Minnesota, and Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA This paper describes methods for conveniently formulating and estimating dynamic linear econometric models under the hypothesis of rational expectations. An econometrically con- venient formula for the cross-equation rational expectations restrictions is derived. Models of error terms and the role of the concept of Granger causality in formulating rational expectations models are both discussed. Tests of the hypothesis of strict econometric exogeneity along the lines of Sims’s are compared with a test that is related to Wu’s. 1. Introduction This paper describes research which aims to provide tractable procedures for combining econometric methods with dynamic economic theory for the purpose of modeling and interpreting economic time series. That we are short of such methods was a message of Lucas’ (1976) criticism of procedures for econometric policy evaluation. Lucas pointed out that agents’ decision rules, e.g., dynamic demand and supply schedules, are predicted by economic theory to vary systematically with changes in the stochastic processes facing agents. This is true according to virtually any dynamic theory that attributes some degree of rationality to economic agents, e.g., various versions of ‘rational expectations’ and ‘Bayesian learning’ hypotheses. The implication of Lucas’ observation is that instead of estimating the parameters of decision rules, what should be estimated are the parameters of agents’ objective functions and of the random processes that they faced historically.