From Bid Time Return to Somewhere in Time: Matheson As Adapter, Adaptation As Transformation, and the Perks of Infidelity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

LCCC Thematic List

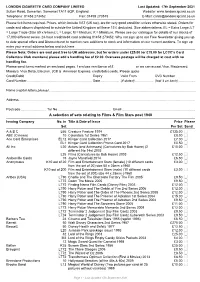

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Last Updated: 17th September 2021 Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] Please tick items required. Prices, which include VAT (UK tax), are for very good condition unless otherwise stated. Orders for cards and albums dispatched to outside the United Kingdom will have 15% deducted. Size abbreviations: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (Size 89 x 64mm); L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature. Please see our catalogue for details of our stocks of 17,000 different series. 24-hour credit/debit card ordering 01458 273452. Why not sign up to our Free Newsletter giving you up to date special offers and Discounts not to mention new additions to stock and information on our current auctions. To sign up enter your e-mail address below and tick here _____ Please Note: Orders are sent post free to UK addresses, but for orders under £25.00 (or £15.00 for LCCC's Card Collectors Club members) please add a handling fee of £2.00. Overseas postage will be charged at cost with no handling fee. Please send items marked on enclosed pages. I enclose remittance of £ or we can accept Visa, Mastercard, Maestro, Visa Delta, Electron, JCB & American Express, credit/debit cards. Please quote Credit/Debit Expiry Valid From CVC Number Card Number...................................................................... Date .................... (if stated).................... (last 3 on back) .................. Name -

THE ULTIMATE SUMMER HORROR MOVIES LIST Summertime Slashers, Et Al

THE ULTIMATE SUMMER HORROR MOVIES LIST Summertime Slashers, et al. Summer Camp Scares I Know What You Did Last Summer Friday the 13th I Still Know What You Did Last Summer Friday the 13th Part 2 All The Boys Love Mandy Lane Friday the 13th Part III The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003) Sleepaway Camp The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning Sleepaway Camp II: Unhappy Campers House of Wax Sleepaway Camp III: Teenage Wasteland Wolf Creek The Final Girls Wolf Creek 2 Stage Fright Psycho Beach Party The Burning Club Dread Campfire Tales Disturbia Addams Family Values It Follows The Devil’s Rejects Creepy Cabins in the Woods Blood Beach Cabin Fever The Lost Boys The Cabin in the Woods Straw Dogs The Evil Dead The Town That Dreaded Sundown Evil Dead 2 VACATION NIGHTMARES IT Evil Dead Hostel Ghost Ship Tucker and Dale vs Evil Hostel: Part II From Dusk till Dawn The Hills Have Eyes Death Proof Eden Lake Jeepers Creepers Funny Games Turistas Long Weekend AQUATIC HORROR, SHARKS, & ANIMAL ATTACKS Donkey Punch Jaws An American Werewolf in London Jaws 2 An American Werewolf in Paris Jaws 3 Prey Joyride Jaws: The Revenge Burning Bright The Hitcher The Reef Anaconda Borderland The Shallows Anacondas: The Hunt for the Blood Orchid Tourist Trap 47 Meters Down Lake Placid I Spit On Your Grave Piranha Black Water Wrong Turn Piranha 3D Rogue The Green Inferno Piranha 3DD Backcountry The Descent Shark Night 3D Creature from the Black Lagoon Deliverance Bait 3D Jurassic Park High Tension Open Water The Lost World: Jurassic Park II Kalifornia Open Water 2: Adrift Jurassic Park III Open Water 3: Cage Dive Jurassic World Deep Blue Sea Dark Tide mrandmrshalloween.com. -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24: Redemption 2 Discs 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 27 Dresses (4 Discs) 40 Year Old Virgin, The 4 Movies With Soul 50 Icons of Comedy 4 Peliculas! Accion Exploxiva VI (2 Discs) 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 400 Years of the Telescope 5 Action Movies A 5 Great Movies Rated G A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 5th Wave, The A.R.C.H.I.E. 6 Family Movies(2 Discs) Abduction 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) About Schmidt 8 Mile Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family Absolute Power 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Accountant, The 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Act of Valor 10,000 BC Action Films (2 Discs) 102 Minutes That Changed America Action Pack Volume 6 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 11:14 Brother, The 12 Angry Men Adventures in Babysitting 12 Years a Slave Adventures in Zambezia 13 Hours Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Heritage Adventures of Mickey Matson and the 16 Blocks Copperhead Treasure, The 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Milo and Otis, The 2005 Adventures of Pepper & Paula, The 20 Movie -

Tobacco Control Policy Making: United States

UCSF Tobacco Control Policy Making: United States Title Tobacco product placement and its reporting to the Federal Trade Commission Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7kd981j3 Authors Polansky, Jonathan R Glantz, Stanton A, PhD Publication Date 2016-07-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Tobacco product placement and its reporting to the Federal Trade Commission Jonathan R. Polansky Onbeyond LLC, Fairfax, California Stanton A. Glantz, PhD University of California, San Francisco ___________________________ University of California, San Francisco This publication is available at www.escholarship.org/uc/item/7kd981j3 July 2016 Tobacco product placement and its reporting to the FTC | 2 Summary of findings The historical record strongly suggests that asking tobacco companies to report their product placement activities and expenditures did not capture all activity in this area. This report compares expenditures for product placement described in internal documents from American Tobacco, Brown & Williamson, Liggett & Myers, Philip Morris and RJ Reynolds tobacco companies with reports the companies were required to submit to the US Federal Trade Commission in the “endorsements and testimonials” category of cigarette promotion and advertising. During that time, in their internal documents, American Tobacco, Brown & Williamson, Philip Morris and RJ Reynolds, or their contracted product placement agents, listed 750 motion pictures as engaged for product placement, 600 of which were released widely to theaters (Appendix). Substantial discrepancies exist between product placement spending described in the internal industry records and the spending reported to the Federal Trade Commission in the “endorsements and testimonials” category. Nearly half (47 percent; $2.3 million of about $5 million) of spending for on-screen product placement described in internal industry records between 1978 and 1994 was not reported in to the FTC in the “endorsements and testimonials” category. -

Starlog Magazine Issue

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: -

Portland's Fritzi Cohen Didn't Have to Be Asked Twice to Join the Cast Of

Swimming Fritzi Cohen’s big fish story is no exaggeration. Portland’s Fritzi Cohen didn’t have to be asked twice to join the cast of Jaws…she was askedf it’s summer three in New England, times. you’ve got to be thinking Jaws. Especially if it’s Ithe summer of 2012, when Universal Studios is behind a monster clambake on Martha’s Vineyard from August 9-12 called “JAWSFEST: The Tribute.” Sponsored by MV Promotions Networks, the event will celebrate Universal’s 100th anniversary as well as the cast and crew of this frighteningly successful film. While the late Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, and Jaws author Peter Benchley will sadly miss the BBQ, the event will still be thronged by well-wishers and fans hoping for glimpses of original cast mem- bers Richard Dreyfuss (Hooper), Susan Backlinie (Chrissie, the most famous night- swimming shark attack victim ever), Lee Fierro (Mrs. Kintner), and possibly Maine’s Fritzi Cohen (under the stage name of Fritzi Jane Courtney), who made the most of her part as a selectwoman in the fictional town of Amity. She reprised her role as Mrs. Taft 1 1 6 p o r t l a n d monthly magazine c l a ssi c S With the Swimming Sharksfrom staff & wire reports Roy Scheider, far left, Murray Hamilton, and Fritzi Cohen grab audience attention during the emergency town council scene in Jaws. in both Jaws 2 (1978) and Jaws: The i’d’d justjust beenbeen working onon Lenny Revenge (1987). Faced with tourism reve- at Charles playhouse inin Boston e C i nues in free fall because of great ff when i got the call to audition. -

The Making of Jaws 1975

The making of jaws 1975 Steven Spielberg is perhaps the most iconic living director, so let's find out how it all started, back in The Making Of Jaws 1/2 [HD] - Duration: TheMakingFilm™ , views · · The Shark Cage from. I had this idea of doing a miniature cage. And putting a little person, into a midget into a miniature cage. A behind the scenes look into the making of Steven Spielberg's JAWS. Production Photographs. Music by. Original poster art for "Jaws" (). (Photo: Universal Pictures/Photofest). Despite the mega success of the movie Jaws, the making of the film. Jaws is a American thriller film directed by Steven Spielberg and based on Peter . Spielberg wanted "some levity" in Jaws, humor that would avoid making it "a dark sea hunt", so he turned to his friend Carl Gottlieb, a comedy writer-actor Release date: June 20, That's a quote from Steven Spielberg on his time directing the horror . said Spielberg (“Spotlight on Location: The Making of Jaws”). Documentary · Excellent and very detailed documentary on the making of a classic. Filled with .. of this documentary (clocking in at minutes) is featured on the Laserdisc and the 2-disc '30th Anniversary' DVD for Jaws (). According to The Making of Steven Spielberg's 'Jaws' () documentary, the shooting star that appears during the night scene where Brody loads his revolver. Fans of the film — about a massive great white shark who terrorizes beachgoers on a resort island — should be thrilled for more rare. If Steven Spielberg's film 'Jaws' made you terrified to go in the ocean, you were not alone! Take a behind-the-scenes look at how Spielberg brought to life. -

NASFA 'Shuttle' Sep 2002

The SHUTTLE September 2002 The Next NASFA Meeting is 21 September at the Regular Time and Location Ñ See Below for Special Info on the Pre-Meeting Program { Oyez, Oyez { Convoy! The next NASFA meeting will be on 21 September 2002 ItÕs field trip time! The September program will be a trip at the regular time (6P) and the regular location. Call to Murfeesboro TN to visit Andre Norton and the High Hallack BookMark at 256-881-3910 if you need directions. Genre WritersÕ Research and Reference Library. The group The meeting will be preceded by the September program will depart from the BookMark parking lot at 9:00A, Saturday Ñ a visit to Andre NortonÕs High Hallack. See the separate 21 September. Show up fed, gassed, and ready to carpool. article at right for details. Plans are for the return trip to start around 3:30P in order to The September after-the-meeting meeting will be at Ray make it back to BookMark in time for the regular club meeting. Pietruszka and Nancy CucciÕs house. Come prepared to cele- Ms Norton has kindly consented to sign books and book- brate numerous September birthdays. plates while we are there. Cameras (including video) are also We need ATMM volunteers for future months, especially welcome. Ms Norton has requested that anything we bring October. We also need donations for the more-or-less annual with us we should take back, with the possible exception of NASFA auction in November. bookplates which may be left (with an appropriately-stamped and addressed envelope) for her to sign at her leisure. -

Kirby Letterhead

SUPERGIRL IN THE BRONZE AGE! October 2015 No.84 $ 8 . 9 5 Supergirl TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 9 Pre-Crisis Supergirl I Death of Supergirl I Rebirths of Supergirl I Superwoman ALAN BRENNERT interview I HELEN SLATER Supergirl movie & more super-stuff! 1 82658 27762 8 Volume 1, Number 84 October 2015 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow TM DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Karl Heitmueller, Jr., with Stephen DeStefano Bob Fingerman Dean Haspiel Kristen McCabe Jon Morris Jackson Publick COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER John Morrow SPECIAL THANKS Cary Bates Elliot S. Maggin Alan Brennert Andy Mangels ByrneRobotics.com Franck Martini BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Glen Cadigan Jerry Ordway FLASHBACK: Supergirl in Bronze . .3 and The Legion George Pérez The Maid of Might in the ’70s and ’80s Companion Ilya Salkind Shaun Clancy Anthony Snyder PRINCE STREET NEWS: The Sartorial Story of the Sundry Supergirls . .24 Gary Colabuono Roger Stern Oh, what to wear, what to wear? Fred Danvers Jeannot Szwarc DC Comics Steven Thompson THE TOY BOX: Material (Super) Girl: Pre-Crisis Supergirl Merchandise . .26 Jim Ford Jim Tyler Dust off some shelf space, ’cause you’re gonna want this stuff Chris Franklin Orlando Watkins FLASHBACK: Who is Superwoman? . .31 Grand Comics John Wells Database Marv Wolfman Elliot Maggin’s Miracle Monday heroine, Kristen Wells Robert Greenberger BACKSTAGE PASS: Adventure Runs in the Family: The Saga of the Supergirl Movie . .35 Karl Heitmueller, Jr. Hollywood’s Ilya Salkind and Jeannot Szwarc take us behind the scenes Heritage Comics Auctions FLASHBACK: Crisis on Infinite Earths #7 . -

Fantastic Fantasy

FANTASTIC FANTASY World Fantasy Award WinnWinninginginging NOVELS Deer Park Public Library 44 Lake Avenue, Deer Park NY 11729 (631) 586-3000 www.deerparklibrary.org 1975: The Forgotten Beasts of Eld by Patricia A. McKillip 1998: The Physiognamy by Jeffrey Ford 1976: Bid Time Return by Richard Matheson 1999: The Antelope Wife by Louise Erdrich 1977: Doctor Rat by William Kotzwinkle 2000: Thraxas by Martin Scott 1978: Our Lady of Darkness by Fritz Leiber 2001: Declare by Tim Powers 1979: Gloriana by Michael Moorcock Galveston by Sean Stewart 1980: Watchtower by Elizabeth A. Lynn 2002: The Other Wind by Ursula Le Guin 1981: The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe 2003: The Facts of Life by Graham Joyce 1982: Little Big by John Crowley Ombria in Shadow by Patricia A. McKillip 1983: Nifft the Lean by Michael Shea 2004: Tooth and Claw by Jo Walton 1984: The Dragon Waiting by John M. Ford 2005: Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke 1985: Mythago Wood by Robert Holdstock 2006: Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami 1986: Song of Kali by Dan Simmons 2007: Soldier of Sidon by Gene Wolfe 1987: Perfume by Patrick Suskind 2008: Ysabel by Guy Gavriel Kay 1988: Replay by Ken Grimwood 2009: The Shadow Year by Jeffrey Ford 1989: Koko by Peter Straub Tender Morsels by Margo Lanagan 1990: Lyoness: Madouc by Jack Vance 2010: The City & The City by China Miéville 1991: Only Begotten Daughter by James Morrow 2011: Who Fears Death by Nnedi Okorafor Thomas the Rhymer by Ellen Kushner 2012: Osama by Lavie Tidhar 1992: Boy’s Life by Robert R. -

The Inventory of the Peter Benchley Collection #956

The Inventory of the Peter Benchley Collection #956 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Benchley, Peter #956 Box 1 Folders 1-2 I. Manuscripts. A. Books. 1. TIME AND A TICKET (non-fiction; Houghton, New York, 1964), draft, TS, edited, 285 p. Folder 3 2. Novels. a. JAWS (Doubleday, New York, 1974). (i) Synopses. (a) Re: early version of book, CTS, 4 p. Folder 4 (b) By Kevin Sellers of Doubleday re: early version of book, TS copy, 3 p., 1973; includes TN from Roberta Pryor. Folder 5 (c ) Re: corrected version of book, TS, 4 p. Folder 6 (ii) Drafts. (a) Rough partial draft, untitled, TS with holograph corrections, pp. 1-174, June 1972; includes: (1) Plot notes. (2) Word count chart/writing calendar. (3) TLS and notes, to PB from “Tony,” 4 p., June 1, 1972. (4) Memo to PB, TS, 4 p. 2 Box 1 cont’d. Folder 7 (b) Untitled draft, CTS, 312 p.; includes memo from PB, 2 p., Jan. 16, 1973. Folders 8-10 (c) Untitled draft, TS, 379 p. Folder 11-12 (d) Pages from early revisions, CTS, approx. 80 p. (revisions and inserts). Folders 13-15 (e) Draft titled GREAT WHITE, TS, edited, 312 p. Folder 16 (f) Draft, CTS, 373 p. Folder 17 (g) Galley proofs, edited, Apr. 11, 1973. Folder 18 (h) Final galley proofs. Folder 19 (i) 5 pages of holograph title suggestions for JAWS. Folder 20 (j) Galley pages for Penguin school edition “retelling,” by Kieran McGovern, 1998; photocopy. 3 Box 2 Folder 1 b. THE DEEP (Doubleday, New York, 1976).